How Did the Practice of Fieldwork Develop?

Trace the development of fieldwork in the discipline’s history.

EARLY ACCOUNTS OF ENCOUNTERS WITH OTHERS

Descriptive accounts of other cultures existed long before anthropologists came on the scene. For centuries, explorers, missionaries, traders, government bureaucrats, and travelers recorded descriptions of the people they encountered. For example, nearly 2,500 years ago, the Greek historian Herodotus wrote about his travels in Egypt, Persia, and the area now known as Ukraine. In the thirteenth century, the Venetian explorer Marco Polo chronicled his travels from Italy across the silk route to China. And the Chinese admiral Zheng He reported on his extended voyages to India, the Middle East, and East Africa in the fifteenth century, seventy years before Christopher Columbus arrived in the Americas. These are just a few of the many early accounts of encounters with other peoples across the globe.

NINETEENTH-CENTURY ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE COLONIAL ENCOUNTER

More information

The 1375 Catalan Atlas, a circular map with many lines, shapes, and symbols representing the known world.

The roots of anthropology and fieldwork lie in the intense globalization of the late nineteenth century. At that time, the increased international movement of Europeans—particularly merchants, colonial administrators, and missionaries—generated a broad array of data that stimulated scientists and philosophers of the day to make sense of the emerging picture of humanity’s incredible diversity (Stocking 1983). They asked questions such as: Who are these other people? Why are their foods, clothing, architecture, rituals, family structures, and political and economic systems so different from ours and from one another’s? Are they related to us biologically? If so, how?

Fieldwork was not a common practice at the beginning of our discipline. In fact, many early anthropologists, such as Edward Burnett Tylor (1832–1917), are now considered “armchair anthropologists” because they did not conduct their own research; instead, they worked at home in their armchairs analyzing the reports of others. One early exception was Lewis Henry Morgan (1818–1881), who conducted fieldwork among Native Americans in the United States. As we discussed in Chapter 2, Tylor and Morgan were leading figures in attempts to organize the accumulating data, to catalogue human diversity, and to make sense of the many questions it raised. These men applied the theory of unilineal cultural evolution—the idea that all cultures would naturally evolve through the same sequence of stages from simple to complex and that the diversity of human cultural expression represented different stages in the evolution of human culture, stages which could be classified in comparison to one another.

THE PROFESSIONALIZATION OF SOCIAL SCIENTIFIC DATA GATHERING AND ANALYSIS

Succeeding generations of anthropologists in Europe and North America rejected unilineal cultural evolution as being too Eurocentric, too ethnocentric, too hierarchical, and lacking adequate data to support its grand claims. Anthropologists in the early twentieth century developed more-sophisticated research methods—particularly ethnographic fieldwork—to professionalize social scientific data gathering.

Franz Boas: Fieldwork and the Four-Field Approach. In the United States, Franz Boas (1858–1942) and his students focused on developing a four-field approach to anthropological research, which included gathering cultural, linguistic, archaeological, and biological data. Boas’s early work among the Indigenous Kwakiutl people of the Pacific Northwest of the United States and Canada firmly grounded him in the fieldwork process, as he learned about Kwakiutl culture through extensive participation in their daily lives, religious rituals, and economic activities. After settling in New York City in the early twentieth century as a professor of anthropology at Columbia University and curator of the American Museum of Natural History, Boas (and his students) embarked on a massive project to document the Native American cultures being devastated by the westward expansion of European settlers across the continent.

More information

A sepia photograph of Franz Boas, a white man, wearing a hooded fur jacket, fur pants, and high boots. His right hand is holding a spear and his left hand is in his jacket pocket. His head is titled downward.

Often called salvage ethnography, Boas’s approach involved the rapid gathering of all available material, including historical artifacts, photographs, recordings of spoken languages, songs, and detailed information about cultural beliefs and practices—from religious rituals to family patterns, gender roles to political structures. With limited time and financial resources, these ethnographers often met with a small number of elderly informants and focused on conducting oral interviews rather than observing actual behavior. Despite the limitations of this emerging fieldwork, these early projects built upon Boas’s commitment to historical particularism when investigating local cultures (see Chapter 2) and defined two continuing characteristics of American anthropology: the four-field approach and cultural relativism (Stocking 1989).

Bronisław Malinowski: Fieldwork and Participation. Across the Pacific Ocean, Bronisław Malinowski (1884–1942) went even further than Boas in developing cultural anthropology’s research methods. Malinowski, a Polish citizen who later became a leading figure in British anthropology, found himself stuck for a year on the Trobriand Islands as a result of World War I. His classic ethnography, Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922), has become most famous for its examination of the Kula ring, an elaborate system of exchange. The ring involved thousands of individuals across many islands, some of whom traveled hundreds of miles by canoe, in an exchange of Kula valuables (in particular, shell necklaces and armbands).

Argonauts also set new standards for fieldwork. In the opening chapter, Malinowski proposes a set of guidelines for conducting fieldwork based on his own experience. He urges fellow anthropologists to stay for a long period in their field sites, learn the local language, get off the veranda (that is, leave the safety of their front porch to mingle with the local people), engage in participant observation, and explore the mundane “imponderabilia of actual life”—the seemingly commonplace, everyday items and activities of people and their communities. Using these strategies enabled Malinowski to analyze the complex dynamics of the Kula ring, both its system of economic exchange and its social networking.

More information

A black and white photograph of Bronisław Malinowski, a white man, wearing knickers and high boots talking with seven people in loincloths. They are seated together on a bench and the white man has an open book on his lap.

Although some of these suggestions may seem obvious to us a century later, Malinowski’s formulation of a comprehensive strategy for understanding local culture was groundbreaking and has withstood the test of time. Of particular importance has been his conceptualization of participant observation as the cornerstone of fieldwork. For anthropologists, it is not enough to observe from a distance. We must learn about people by participating in their daily activities, walking in their shoes, seeing through their eyes. Participant observation gives depth to our observations, provides intimate knowledge of people and their communities, and helps guard against mistaken assumptions based on observation from a distance (Kuper 1983).

More information

Africa is labeled. Sudan and Ethiopia are labeled. Nuer is highlighted and labeled in and around Sudan and Ethiopia.

E. E. Evans-Pritchard and British Social Anthropology. Between the 1920s and 1960s, many British social anthropologists viewed anthropology as a science designed to discover the component elements and patterns of society (see Chapter 2). Fieldwork was their key methodology for conducting their scientific experiments. Adopting a synchronic approach, they sought to control their experiments by limiting consideration of the larger historical and social context in order to isolate as many variables as possible.

E. E. Evans-Pritchard (1902–1973), one of the leading figures during this period, wrote a classic ethnography in this style. In The Nuer (1940), based on his research with a group of rural Sudanese people over eleven months between 1930 and 1936, Evans-Pritchard systematically documents the group’s social structures—political, economic, and kinship—and captures the intricate details of community life. But later anthropologists have criticized his failure to consider the historical context and larger social world. Indeed, the Nuer in Evans-Pritchard’s study lived under British occupation in the Sudan, and many Nuer participated in resistance to British occupation despite an intensive British pacification campaign against the Sudanese during the time of Evans-Pritchard’s research. Later anthropologists have questioned how he could have omitted such important details and ignored his status as a British subject when it had such potential for undermining his research.

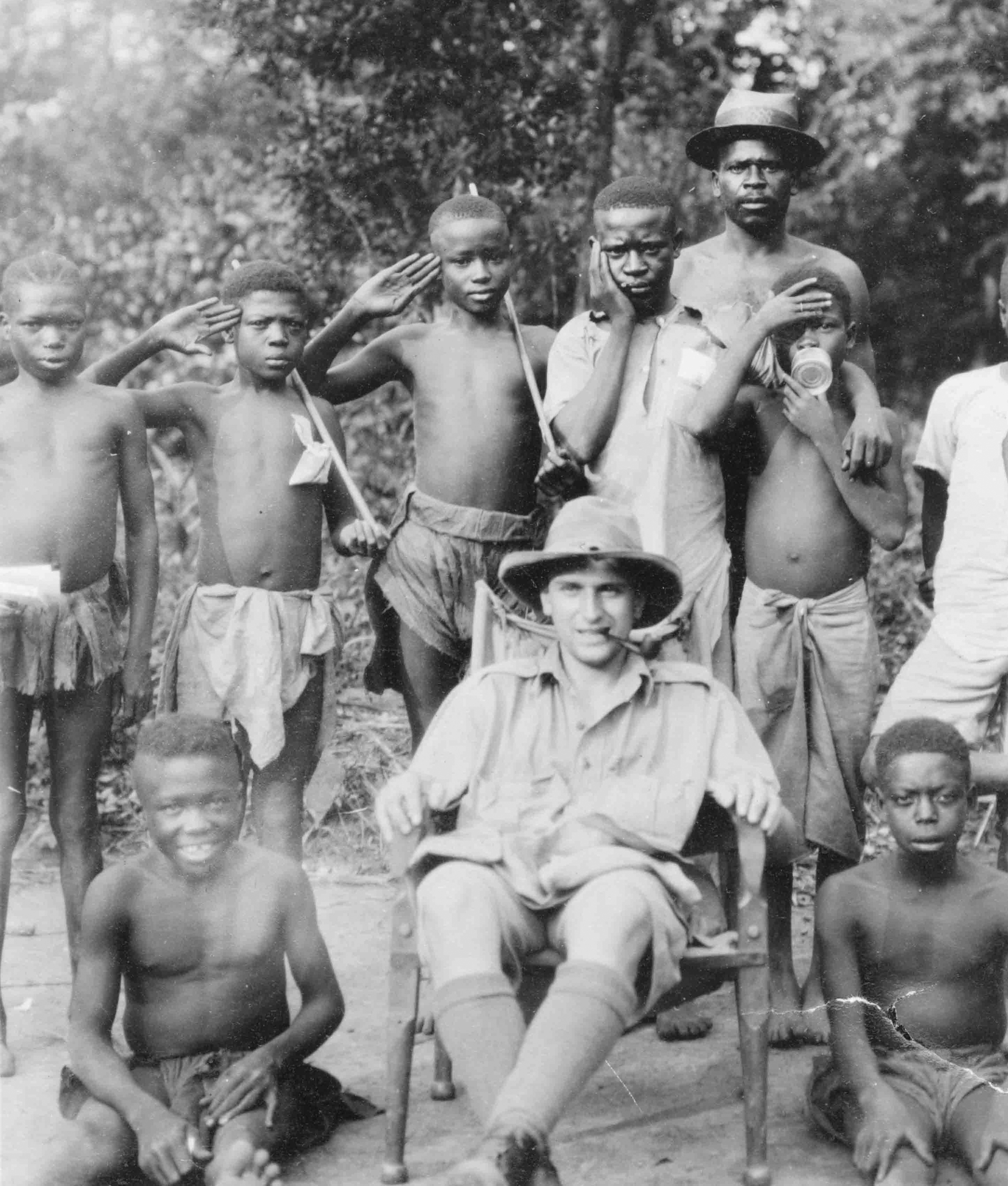

More information

A black and white photograph of E. E. Evans-Pritchard, a white man, wearing a wide-brimmed hat, collared shirt, and knee-high socks smoking a pipe sitting in a chair. He is surrounded by Nuer boys and men wearing loincloths all with short hair. A few boys salute and one man wears a hat. Two boys sit on the floor next to the white man and one boy is smiling.

More information

Australia, New Zealand, and Samoa are labeled.

Margaret Mead: Fieldwork and Public Anthropology. Margaret Mead (1901–1978), a student of Franz Boas, conducted pioneering fieldwork in the 1920s, famously examining teen sexuality in Coming of Age in Samoa (1928) and, later, the wide diversity of gender roles in three separate groups in Papua New Guinea (1935). Perhaps most significant, however, Mead mobilized her fieldwork findings to engage in crucial scholarly and public debates at home in the United States. At a time when many in the United States argued that gender roles were biologically determined, Mead’s fieldwork testified to the fact that U.S. cultural norms were not found cross-culturally but were culturally specific. Mead’s unique blend of fieldwork and dynamic writing provided her with the authority and opportunity to engage a broad public audience and made her a powerful figure in the roiling cultural debates of her generation.

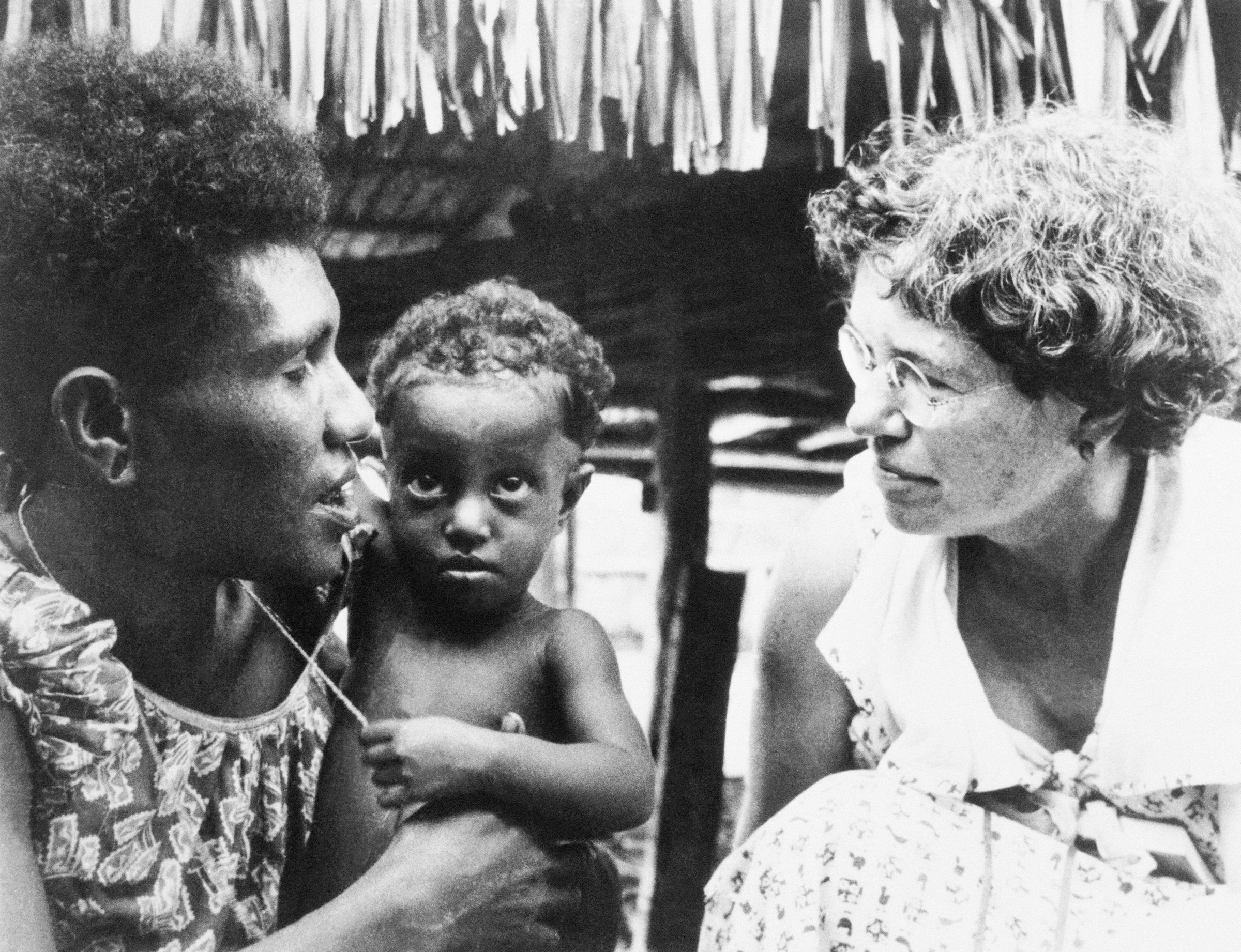

More information

A black and white photo of Margaret Mead, a white woman with short hair and glasses, speaking to a woman holding a baby. The woman and baby both have short curly hair and the baby is staring toward the camera with large, round eyes.

Zora Neale Hurston: Fieldwork in the American South. Zora Neale Hurston (1891–1960), perhaps best known as a leading literary figure in the Harlem Renaissance of the early twentieth century, was, like Margaret Mead, a student of Franz Boas at Barnard College and Columbia University. While Mead conducted fieldwork in the South Pacific, as part of his salvage ethnography project Boas sent Hurston to the American South, particularly Florida, to conduct intensive fieldwork on Black folk culture. Hurston, who grew up in Eatonville, Florida, just north of Orlando, traveled throughout central and northern Florida, across the southeastern United States, and later to Jamaica, the Bahamas, and Honduras. In reams of field notes, photographs, audio recordings, and film reels, Hurston documented folk tales, stories, sayings, work songs, religious rituals, character sketches, life histories, spirituals, blues music, and other ethnographic material, culminating in her book Mules and Men (1935) on southern Black folklore and folk religion. Though Hurston had been sent to conduct salvage ethnography on what Boas and others incorrectly considered a dying and even inferior cultural tradition, her work captured the vitality of local storytelling as central to the ongoing construction of a dynamic Black cultural tradition and community identity.

More information

A black and white photo of Zora Neale Hurston, a Black woman, wearing a hat that is slightly tilted to the right. She wears a top with a sparkly design on the collar and is smiling brightly.

Hurston proved to be several generations ahead of her time in anthropology: She conducted research in her own community rather than in a distant place years before that became common. She broke with anthropological writing expectations, writing for a popular rather than a scholarly audience by merging inventive literary conventions with her rich ethnographic data. Her fieldwork and its characters—loggers, migrant farm workers, turpentine boilers, bootleggers, and juke joint operators—provided rich material for her creative work for years to come. Over the course of her career, she published four novels, other nonfiction books, more than fifty stories, essays, and collections of poetry, and she directed numerous plays and ethnographic films.

The People of Puerto Rico: A Turn to the Global. During the 1950s, a team of anthropologists headed by Julian Steward (1902–1972) and including Sidney Mintz (1922–2015) and Eric Wolf (1923–1999) engaged in a collaborative fieldwork project at multiple sites on the island of Puerto Rico. Steward’s resulting ethnography, The People of Puerto Rico (1956), marked the beginning of a significant anthropological turn away from studies of seemingly isolated, small-scale, nonindustrial societies toward studies that examined the integration of local communities into a modern world system. In particular, the new focus explored the impacts of colonialism and the spread of capitalism on local people. Mintz, in Sweetness and Power (1985), later expanded his fieldwork interests in Puerto Rican sugar production to consider the intersections of local histories and local production of sugar with global flows of colonialism and capitalism. Wolf, in Europe and the People Without History (1982), continued a lifetime commitment to reasserting forgotten local histories—or the stories of people ignored by a European-dominated history—into the story of the modern world economic system. Historically, Wolf argued, local cultures have been interconnected on the world level, not isolated from one another. And their unique histories have themselves shaped global processes and interactions, not just been shaped by them.

Annette Weiner: Feminism and Reflexivity. In the 1980s, anthropologist Annette Weiner (1933–1997) retraced Malinowski’s footsteps to conduct a new study of the Trobriand Islands sixty years later. Weiner quickly noticed aspects of Trobriand culture that had not surfaced in Malinowski’s writings. In particular, she took careful note of the substantial role women played in the island economy. Whereas Malinowski had focused his attention on the elaborate male-dominated system of economic exchange among islands, Weiner found that women had equally important economic roles and equally valuable accumulations of wealth.

More information

A black and white photograph of Barbara Myerhoff, a young white woman with dark hair, standing between two senior citizens with her arms around them. One person wears glasses and has a flower in their lapel. The other person has short, white hair. They are all looking at a book.

In the course of her fieldwork, Weiner came to believe that Malinowski’s conclusions were not necessarily wrong but were incomplete. By the time of Weiner’s study (1988), anthropologists were carefully considering the need for reflexivity in conducting fieldwork—that is, a critical self-examination of the role of the anthropologist and an awareness that who one is affects what one finds out. Malinowski’s age and gender influenced what he saw and what others were comfortable telling him. By the 1980s, feminist anthropologists such as Weiner and Kathleen Gough (1971), who revisited Evans-Pritchard’s work with the Nuer, were pushing anthropologists to be more critically aware of how their own position in relationship to those they study affects their scope of vision.

Barbara Myerhoff: A Turn to Home. The first book written by Barbara Myerhoff (1935–1985), Peyote Hunt (1974), traces the pilgrimage of the Indigenous Huichol people across the Sierra Madre of Mexico as they retell, reclaim, and reinvigorate their religious myths, rituals, and symbols. In her second book, Number Our Days (1978), Myerhoff turns her attention closer to home. Her fieldwork focuses on the struggles of older Jewish immigrants in a Southern California community—particularly the Aliyah Senior Citizens’ Center, through which her subjects create and remember ritual life and community as a means of controlling their daily activities and faculties as they age. Their words pour off the pages of Myerhoff’s book as she allows them to tell their life stories. As a character in her own writing, Myerhoff traces her interactions and engagements with the members of the center and reflects poignantly on the process of self-reflection and transformation that she experiences as a younger Jewish woman studying a community of older Jews.

Coming nearly fifty years after Hurston’s fieldwork, Number Our Days marks a broader turn in anthropology from the study of the “other” to the study of the self—what Victor Turner calls in his foreword to Myerhoff’s book “being thrice-born.” The first birth is in our own culture. The second birth immerses the anthropologist in the depths of another culture through fieldwork. Finally, the return home is like a third birth as the anthropologist rediscovers their own culture, now strange and unfamiliar in a global context.

ENGAGED ANTHROPOLOGY

Over the past thirty years, an increasing number of anthropologists, including Nancy Scheper-Hughes, whose work bookends this chapter, have identified their work as engaged anthropology. Engaged anthropologists intentionally seek to apply the research strategies and analytical perspectives of the discipline to address the concrete challenges facing local communities and the world at large. In this regard, engaged anthropology challenges the assumptions that anthropology, as a science, should focus on producing objective, unbiased, neutral accounts of human behavior and that anthropologists should work as disengaged observers while conducting research. Engaged anthropologists argue that in a world of conflict and inequality, social scientists must develop an active, politically committed, and morally engaged practice. Engaged anthropology, then, is characterized by a commitment not only to revealing and critiquing but also to confronting systems of power and inequality. Design, implementation, and analysis of research involve close collaboration with colleagues and co-researchers in the community. Advocacy and activism with local communities on matters of mutual concern are central tenets of engaged anthropology (Scheper-Hughes 1995; Speed 2006).

As we have seen in the work of Boas and Mead, for example, this form of engagement is not new to anthropology. The field has had a strong strain of engagement since its inception. As early as 1870, John W. Powell, the first director of the U.S. Bureau of Ethnology, testified before Congress about the genocide of Native Americans following the United States’ westward expansion and construction of the railroads. Hurston vividly illuminated the culture and folklore of the early twentieth-century African American diaspora (1935, 1938; McClaurin 2007; King 2019). Lakota anthropologist Beatrice Medicine (1924–2005) long advocated for the rights of women, children, Native Americans, and gay, lesbian, and transgender people. In recent decades, this focus on engagement, advocacy, and activism has become increasingly central to anthropologists’ research strategies (Low and Merry 2010).

Glossary

- salvage ethnography Fieldwork strategy developed by Franz Boas to collect cultural, material, linguistic, and biological information about Native American populations being devastated by the westward expansion of European settlers.

- cultural relativism Understanding a group’s beliefs and practices within their own cultural context, without making judgments.

- participant observation A key anthropological research strategy involving both participation in and observation of the daily life of the people being studied.

- reflexivity A critical self-examination of the role the anthropologist plays and an awareness that one’s identity affects one’s fieldwork and theoretical analyses.

- engaged anthropology Application of the research strategies and analytical perspectives of anthropology to address concrete challenges facing local communities and the world at large.