![]() The Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution

What major social and political crises rocked the colonies in the late seventeenth century?

COLONIES IN CRISIS

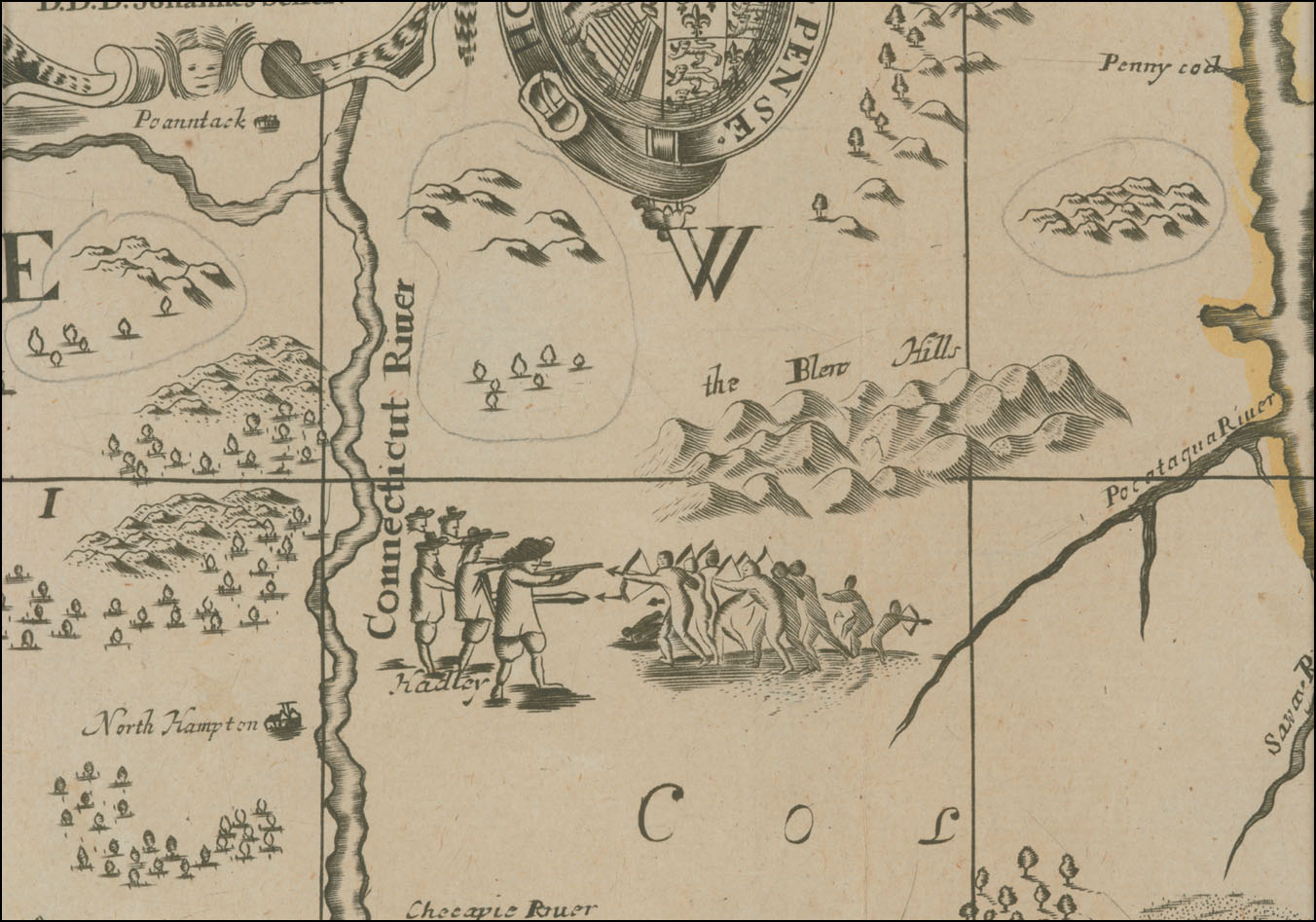

A scene from King Philip’s War, included on a 1675 map of New England.

King Philip’s War of 1675–1676 and Bacon’s Rebellion the following year coincided with disturbances in other colonies. In Maryland, where the proprietor, Lord Baltimore, in 1670 suddenly restricted the right to vote to owners of fifty acres of land or a certain amount of personal property, a Protestant uprising unsuccessfully sought to oust his government and restore the suffrage for all freemen. As the English colonies grew in population and the balance of power shifted, wars broke out with their Native allies. Colonists also fought with Native nations on their borders, as settlers squatted on Indian hunting and gathering lands. The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 (discussed in Chapter 1) indicated that the crisis of colonial authority was not confined to the British empire.

VOICES OF FREEDOM

MARYLAND ACT CONCERNING NEGROES AND OTHER SLAVES (1664)

Like Virginia, Maryland in the 1660s enacted laws to clarify questions arising from the growing importance of slavery. This law made all Black servants in the colony slaves for life, and required a white woman who married an enslaved man to serve her husband’s owner.

Listen as you read

Be it enacted by the Right Honorable the Lord Proprietary by the advice and consent of the upper and lower house of this present General Assembly, that all Negroes or other slaves already within the province, and all Negroes and other slaves to be hereafter imported into the province, shall serve durante vita [for life]. And all children born of any Negro or other slave shall be slaves as their fathers were, for the term of their lives.

And forasmuch as divers freeborn English women, forgetful of their free condition and to the disgrace of our nation, marry Negro slaves, by which also divers suits may arise touching the issue [children] of such women, and a great damage befalls the masters of such Negroes for prevention whereof, for deterring such freeborn women from such shameful matches. Be it further enacted by the authority, advice, and consent aforesaid, that whatsoever freeborn woman shall marry any slave from and after the last day of this present Assembly shall serve the master of such slave during the life of her husband. And that all the issue of such freeborn women so married shall be slaves as their fathers were. And be it further enacted, that all the issues of English or other freeborn women that have already married Negroes shall serve the masters of their parents till they be thirty years of age and no longer.

LETTER BY AN INDENTURED SERVANT (March 20, 1623)

Only a minority of emigrants from Europe to the English colonies were fully free. Indentured servants were men and women who surrendered their freedom for a specified period of time in exchange for passage to the Americas. This letter that Richard Frethorne sent from Virginia to his parents in England expresses complaints voiced by many indentured servants.

Listen as you read

LOVING AND KIND FATHER AND MOTHER:

My most humble duty remembered to you, hoping in god of your good health, as I myself am. . . . This is to let you understand that I your child am in a most heavy case by reason of the country, [which] is such that it causeth much sickness, [such] as the scurvy and the bloody flux and divers [many] other diseases, which maketh the body very poor and weak. And when we are sick there is nothing to comfort us; for since I came out of the ship I never ate anything but peas, and loblollie (that is, water gruel). As for deer or venison I never saw any since I came into this land. . . . And I have nothing to comfort me, nor is there nothing to be gotten here but sickness and death, except [in the event] that one had money to lay out in some things for profit. But I have nothing at all—no, not a shirt to my back but two rags, nor clothes but one poor suit, nor but one pair of shoes, but one pair of stockings, but one cap, [and] but two bands [collars]. . . . And indeed so I find it now, to my great grief and misery; and [I] saith that if you love me you will redeem me suddenly, for which I do entreat and beg. And if you cannot get the merchants to redeem me for some little money . . . Wherefore, for God’s sake, pity me. I pray you to remember my love to all my friends and kindred. I hope all my brothers and sisters are in good health, and as for my part I have set down my resolution that certainly will be; that is, that the answer of this letter will be life or death to me.

ROT

Richard Frethorne

The Glorious Revolution

Turmoil in England also reverberated in the colonies. In 1688, the long struggle for domination of English government between Parliament and the crown reached its culmination in the Glorious Revolution, which established parliamentary supremacy once and for all and secured the Protestant succession to the throne. When Charles II died in 1685, he was succeeded by his brother James II (formerly the duke of York), a practicing Catholic and a believer that kings ruled by divine right. In 1687, James decreed religious toleration for both Protestant Dissenters and Catholics. The following year, the birth of James’s son raised the alarming prospect of a Catholic succession. A group of English aristocrats invited the Dutch nobleman William of Orange to assume the throne with his wife, James’s Protestant daughter Mary, in the name of English liberties. As the landed elite and leaders of the Anglican Church rallied to William and Mary’s cause, James II fled and the revolution was complete.

Unlike the broad social upheaval that marked the English Civil War of the 1640s, the Glorious Revolution was in effect a coup engineered by a group of aristocrats with an ambitious Dutch prince. But the overthrow of James II entrenched more firmly than ever the notion that liberty was the birthright of all Englishmen and that the king was subject to the rule of law. To justify the ouster of James II, Parliament in 1689 enacted an English Bill of Rights, which listed parliamentary powers such as control over taxation as well as rights of individuals, including trial by jury. In the same year, the Toleration Act allowed Protestant Dissenters (but not Catholics) to worship freely, although only Anglicans could hold public office.

As always, English politics were mirrored in the American colonies. After the Glorious Revolution, Protestant domination was secured in most of the colonies, while Catholics and Dissenters suffered various forms of discrimination. Throughout English America the Glorious Revolution powerfully reinforced among the colonists the sense of sharing a proud legacy of freedom and Protestantism with England.

The Glorious Revolution in America

The Glorious Revolution exposed fault lines in colonial society and offered local elites an opportunity to regain authority that had recently been challenged. Until the mid-1670s, the North American colonies had essentially governed themselves, with little interference from England. Governor Berkeley ran Virginia as he saw fit; proprietors in New York, Maryland, and Carolina governed in any fashion they could persuade colonists to accept; and New England colonies elected their own officials and openly flouted trade regulations. In 1675, however, England established the Lords of Trade to oversee colonial affairs. Three years later, the Lords questioned the Massachusetts government about its compliance with the Navigation Acts. They received the surprising reply that since the colony had no representatives in Parliament, the acts did not apply to it unless the Massachusetts General Court approved.

In the 1680s, England moved to reduce colonial autonomy. Shortly before his death, James II between 1686 and 1689 combined Connecticut, Plymouth, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, New York, and East and West Jersey into a single super-colony, the Dominion of New England. It was ruled by the former New York governor Sir Edmund Andros, who did not have to answer to an elected assembly. These events reinforced the impression that James II was an enemy of freedom.

In 1689, news of the overthrow of James II triggered rebellions in several American colonies. In April, the Boston militia seized and jailed Edmund Andros and other officials, whereupon the New England colonies reestablished the governments abolished when the Dominion of New England was created. In May, a rebel militia headed by Captain Jacob Leisler established a Committee of Safety and took control of New York. Two months later, Maryland’s Protestant Association overthrew the government of the colony’s Catholic proprietor, Lord Baltimore.

All of these new regimes claimed to have acted in the name of English liberties and looked to London for approval. But the degrees of success of these coups varied markedly. Concluding that Lord Baltimore had mismanaged the Maryland colony, William and Mary revoked his charter (although the proprietor retained his land and rents) and established a new, Protestant-dominated government. In 1715, after the Baltimore family had converted to Anglicanism, proprietary power was restored. But the events of 1689 transformed the ruling group in Maryland and put an end to the colony’s unique history of religious toleration.

The outcome in New York was far different. Although it was not his intention, Jacob Leisler’s regime divided the colony along ethnic and economic lines. Members of the Dutch majority reclaimed local power after more than two decades of English rule, while bands of rebels ransacked the homes of wealthy New Yorkers. William and Mary refused to recognize Leisler’s authority and dispatched a new governor, backed by troops. Many of Leisler’s followers were imprisoned, and he himself was executed. For generations, the rivalry between Leisler and anti-Leisler parties polarized New York politics.

The New England colonies, after deposing Governor Andros, lobbied hard in London for the restoration of their original charters. Most were successful, but Massachusetts was not. In 1691, the crown issued a new charter that absorbed Plymouth into Massachusetts and transformed the political structure of the Bible Commonwealth. Town government remained intact, but henceforth property ownership, not church membership, would be the requirement to vote in elections for the General Court. The governor was now appointed in London rather than elected. Massachusetts became a royal colony, the majority of whose voters were no longer Puritan “saints.” Moreover, it was required to abide by the English Toleration Act of 1689—that is, to allow all Protestants to worship freely.

These events produced an atmosphere of considerable tension in Massachusetts, exacerbated by raids by allied Native and French fighters on the northern border of New England. The advent of religious toleration heightened anxieties among the Puritan clergy, who considered other Protestant denominations a form of heresy. Indeed, quite a few Puritans thought they saw the hand of Satan in the events of 1690 and 1691.

The Salem Witch Trials

![]() Salem Witch Trials

Salem Witch Trials

Belief in magic, astrology, and witchcraft was widespread in seventeenth-century Europe and America, existing alongside the religious beliefs sanctioned by the clergy and churches. Witches were individuals, usually women, who were accused of having entered into a pact with the devil to obtain supernatural powers, which they used to harm others or to interfere with natural processes. When a child was stillborn or crops failed, many believed that witchcraft was at work.

In Europe and the colonies, witchcraft was punishable by execution. It is estimated that between the years 1400 and 1800, more than 50,000 people were executed in Europe after being convicted of witchcraft. Witches were, from time to time, hanged in seventeenth-century New England. Most were women beyond childbearing age who were outspoken, economically independent, or estranged from their husbands, or who in other ways violated traditional gender norms.

An engraving from Ralph Gardiner’s England’s Grievance Discovered, published in 1655, depicts women hanged as witches in England. The letters identify local officials: A is the hangman, B the town crier, C the sheriff, and D a magistrate.

Until 1692, the prosecution of witches had been sporadic. But in that year, a series of trials and executions took place in Salem, Massachusetts, that made its name to this day a byword for fanaticism and persecution. The Salem witch trials began when several young girls began to suffer fits and nightmares, attributed by their elders to witchcraft. Soon, three “witches” had been named, including Tituba, a Native woman from the Caribbean who was enslaved in the home of one of the girls. Since the only way to avoid prosecution was to confess and name others, accusations of witchcraft began to snowball. By the middle of 1692, hundreds of residents of Salem had come forward to accuse their neighbors. Although many of the accused confessed to save their lives, fourteen women and five men were hanged, protesting their innocence to the end.

As accusations and executions multiplied, it became clear that something was seriously wrong with the colony’s system of justice. The governor of Massachusetts dissolved the Salem court and ordered the remaining prisoners released. The events in Salem discredited the tradition of prosecuting witches and encouraged prominent colonists to seek scientific explanations for natural events such as comets and illnesses, rather than attribute them to magic.

Glossary

- Glorious Revolution

- A coup in 1688 engineered by a small group of aristocrats that led to William of Orange taking the British throne in place of James II.

- English Bill of Rights

- A series of laws enacted in 1689 that inscribed the rights of English men into law and enumerated parliamentary powers such as taxation.

- Lords of Trade

- An English regulatory board established to oversee colonial affairs in 1675.

- Dominion of New England

- Consolidation into a single colony of the New England colonies—and later New York and New Jersey—by royal governor Edmund Andros in 1686; dominion reverted to individual colonial governments three years later.

- English Toleration Act

- A 1690 act of Parliament that allowed all English Protestants to worship freely.

- Salem witch trials

- A crisis of trials and executions in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1692 that resulted from anxiety over witchcraft.

- divers

- The archaic word for “some” or “various.” Close in meaning to our word, “diverse.”

- forgetful of their free condition

- Of course, this wasn’t a literal use of “forgetful,” but rather a way to refer to women whom the law accused of “disgrace” and to shame a white woman who was in a relationship with a Black man to remember her place in society.

- as their fathers were

- Children of a previously free woman who married an enslaved man would also be enslaved. Compare this to the Virginia law that stated that the condition of the mother would define the condition of the child.

- scurvy and the bloody flux

- Both scurvy and the “bloody flux” (dysentery) were experienced by people without access to a healthy diet. Scurvy is caused by a lack of vitamin C for an extended period. However, many indentured servants often ate a nutrient-deficient diet as Frethorne described. Dysentery is a bacterial disease usually spread through contaminated food or water.

- lay out

- Frethorne means “items to sell.”

- redeem me suddenly

- As an indentured servant, Frethorne’s labor and liberty were sold to another for a period of time, usually seven years. Here he is asking his parents to pay the cost of the rest of his indenture so that he is free of the obligation to continue the arrangement.

- life or death

- It’s quite likely that Frethorne is not exaggerating here. Many indentured servants died from the harsh conditions and diseases of the era before their terms expired.

- durante vita

- This is in contrast to indentured servants who had a term of indenture (usually seven years), rather than a lifetime of enslavement.