STUDY UNIT 1.12 Using Psychology to Learn Psychology

Explore...

- How can this text help you learn psychology?

- Why are distributed practice and self-testing effective study tools?

- How can you take effective notes in class?

- How can you manage your time, technology, and motivation?

What is your approach to studying and learning new material? Do you start reading your assignments ten minutes before they are due—fearing a pop quiz when you get to class—or do you make time in your schedule to read the material and test yourself on your comprehension? Do you approach each assignment as a painful task to be completed, or as a journey of exploration that will bring you new tools for thinking about the world?

Many students have developed a personalized study system that works for them, but they must adapt that system to their college studies. College requires strong time-management skills as well as metacognition, an awareness and understanding of your own thought processes.

The interactive ebook you are reading, Interactive Psychology: People in Perspective, is a learning system developed to help you learn psychology. It uses psychological research about comprehension, learning, memory, and recall, to increase your engagement with your course, your motivation to learn psychological concepts, and your retention of key ideas. Let’s look specifically at how the learning tools in Interactive Psychology will help you learn.

Chapter outlines.

Each chapter—including this one!—starts with an outline of the content to be covered. By scanning this outline, you engage in a process called surveying or previewing (McDaniel et al., 2009; Robinson, 1970). Previewing a chapter before you read it shifts your mind into active gear, giving you a mental outline of the chapter’s content and organization and helping you to see connections among ideas. Once you know the general direction of the content, reading will be faster and easier.

Study units. Each chapter is divided into short study units, most no longer than 1,000 words. Study units break the material into shorter chunks, helping to prevent information overload (Thalmann et al., 2019). (For additional information about chunking, see Study Unit 7.4.)

Explore questions.

You may have noticed that each study unit begins with a series of Explore questions. These questions signal the most important material in the study unit, pointing to the topics that you will most likely discuss in class or encounter on quizzes and exams (R. E. Mayer, 2014; R. Moreno & Mayer, 2007). They also set your mind working: When you start a reading assignment by asking questions, your mind looks for the answers as you read, helping you focus on key concepts. These Explore questions also activate your schema, which is your existing framework of knowledge. Connecting what you read to what you already know (even if your information is somewhat limited) helps you better grasp the material (C. H. Lee & Kalyuga, 2014). Many studies have shown that pre-questions increase the retention of material, so be sure to engage with the Explore questions as you begin each study unit (Carpenter et al., 2018; Dunlosky et al., 2013; Fleck et al., 2017).

Interactive figures and videos. Many study units include interactives that allow you to experience a phenomenon, check your intuition, explore cultural similarities and differences, evaluate scientific evidence, examine brain structures and functions, or watch videos that explain key concepts or offer fascinating case studies. You’ve seen some of these as you’ve walked through this chapter. One goal of the interactives is to increase your engagement with the concepts, because it’s your interest more than your ability that predicts how much information you will remember from this class (Naceur & Scheifele, 2005). In addition, the interactives provide active learning opportunities that will help you develop the skills and knowledge you need to succeed in introductory psychology. Throughout the text, you’ll encounter the following types of interactives in each chapter:

![]() Analyze the Data

Analyze the Data

Understand and analyze scientific data.

![]() Explore the Science

Explore the Science

Investigate how psychologists conduct and perform research.

![]() Make It Personal

Make It Personal

Reflect on your own behaviors and beliefs.

![]() Experience It Yourself

Experience It Yourself

Experience psychological concepts and methods directly.

![]() Interpret the Example

Interpret the Example

Apply psychological concepts to everyday life.

![]() Examine Different Perspectives

Examine Different Perspectives

Explore the breadth and diversity of human experiences.

Check Your Understanding questions.

As you’ve seen, each study unit concludes with a Check Your Understanding question that tests your comprehension, sometimes asking you to apply concepts to different scenarios. As research has shown, any activity that involves testing yourself “makes your learning both more durable and flexible” (Bjork & Bjork, 2011, p. 63). In short, learning requires practice, and the Check Your Understanding questions provide exactly that (Pennebaker et al., 2013; Shireman, 2009). Testing yourself on information rather than simply rereading it not only improves learning of current material but also enhances future learning (Chan et al., 2018; Rowland, 2014).

Each time you answer a question, you receive specific feedback that will help you remember the information. For feedback to be most effective, you must recognize it as useful and act on it. When you see feedback to questions you got wrong, try to construct a strategy for remembering that information for next time (Gibbs & Simpson, 2004; Lizzio & Wilson, 2008; Quinton & Smallbone, 2010; A. C. Smith et al., 2019; Wojcikowski & Kirk, 2013).

We’ve looked at specific ways in which this etext has been built to help you learn. Psychological science offers many other suggestions to help you succeed in college.

Distribute your practice.

Studies have shown that 25 to 50 percent of college students rely on cramming, or studying intensively on the night before an exam, because they have neglected their studies between exams (McIntyre & Munson, 2008). Research suggests that you may learn and retain much more information if you engage in distributed practice, spreading out your learning into shorter sessions over a longer period of time. Studies have shown that on average, people retain about 47 percent of studied information when they engage in distributed practice, but only about 37 percent when they cram (Cepeda et al., 2008).

Test yourself. Testing yourself is one of the best ways to learn. In fact, it is much more effective than rereading what you have already read, practicing with concept maps, or simply assessing what you know and do not know (Butler, 2010; Dunlosky et al., 2013; Karpicke & Blunt, 2011; Roediger & Karpicke, 2006). In addition, self-testing enhances your ability to answer similar types of questions on quizzes and exams. For example, the more you practice answering multiple-choice questions, the better you become at answering multiple-choice questions (Kang et al., 2007).

Take detailed and clear notes while listening to lectures.

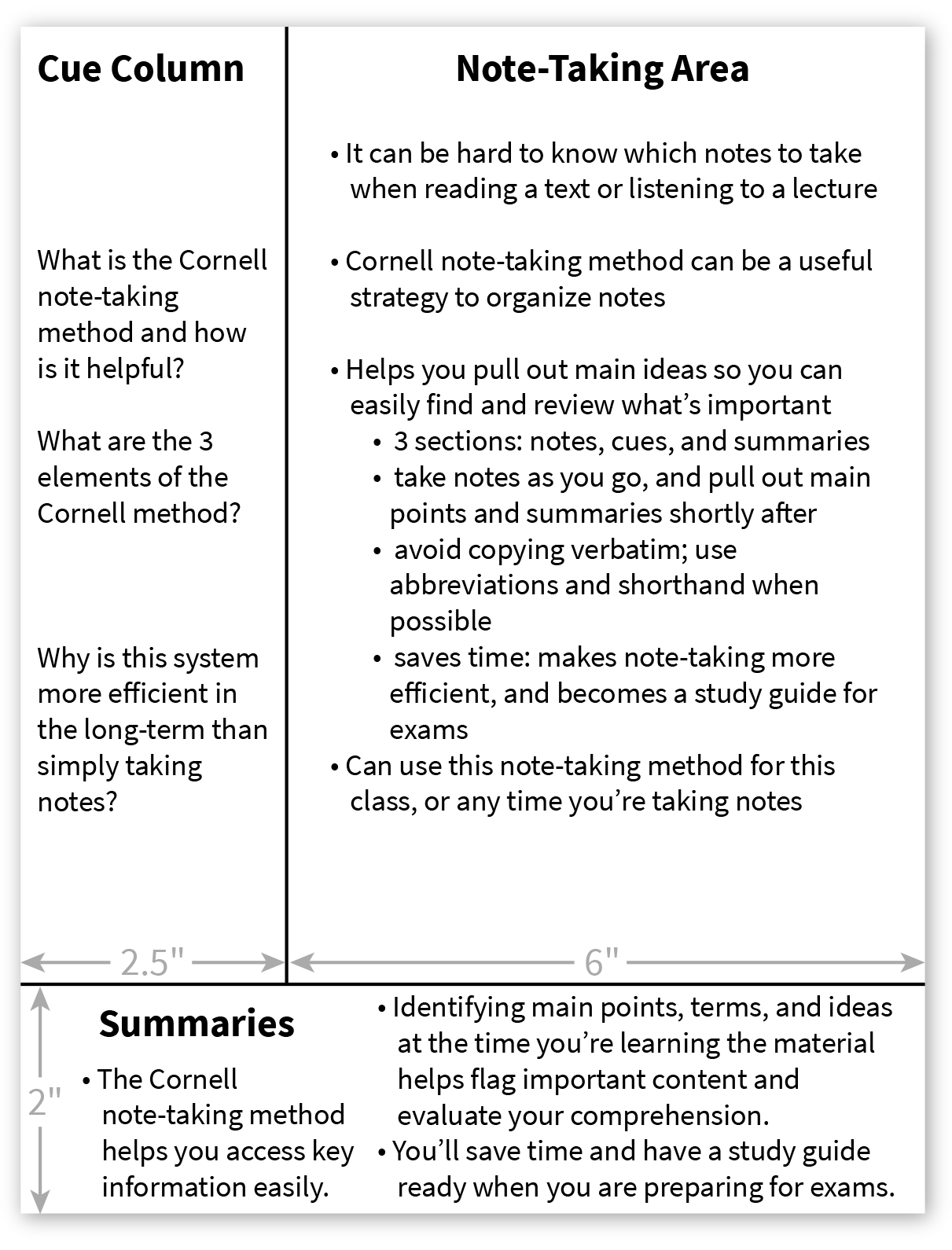

Human memory is subject to many errors (Schacter, 1999, 2001). A good way to avoid memory errors is to take good, but not exhaustive, lecture notes by hand. By doing so, you prevent yourself from having to fill in the gaps later on, perhaps introducing errors into your thinking. The Cornell note-taking method, outlined in FIGURE 1.27, can be quite effective. It allows you to quiz yourself on material as you review your notes, but the notes you take with the Cornell method should not be your sole method of reviewing the material as you prepare for an exam.

More information

An example of the Cornell note-taking method is shown in which it describes the Cornell note-taking method. This method divides notes into three sections: cue column, note-taking area, and summaries. The cue column appears on the left-hand side of the page and is two and a half inches in width. Text in the cue column reads as follows: What is the Cornell note-taking method and how is it helpful? What are the 3 elements of the Cornell method? Why is this system more efficient in the long-term than simply taking notes? The Note-Taking Area is a column six inches in width and features several bulleted notes. The notes read as follows: First bullet point: It can be hard to know which notes to take when reading a text or listening to a lecture. Second bullet point: Cornell note-taking method can be a useful strategy to organize notes. Third bullet point: Helps you pull out main ideas so you can easily find and review what’s important. Sub-notes of third bullet point: 3 sections: notes, cues, and summaries. Take notes as you go, and pull out main points and summaries shortly after. Avoid copying verbatim; use abbreviations and shorthand when possible. Saves time: makes note-taking more efficient, and becomes a study guide for exams. Fourth major bullet point: Can use this note-taking method fo this class, or any time you’re taking notes. The bottom two inches of the page is the summaries section, which features three bullet points. First bullet point: The Cornell note-taking method helps you access key information easily. Second bullet point: Identifying main points, terms, and ideas at the time you’re learning the material helps flag important content and evaluate your comprehension. Third bullet point: You’ll save time and have a study guide ready when you are preparing for exams.

FIGURE 1.27 The Cornell Note-Taking Method

The Cornell note-taking method is an excellent way to organize your notes for easy reference and self-review. Divide your page into three sections: (1) The note-taking area is the bulk of your page. Use this space to jot down key concepts, paraphrasing in your own words and using abbreviations whenever possible. (2) The cue column is a space to remind yourself what was important from your reading or lecture. Either as you are taking notes or within 24 hours after, identify the important themes that you may be tested on. Add these to the cue column, lining up your cues with the relevant notes to easily locate the answers to your questions. Then use the cue column to study for exams. (3) Use the summary section to write brief summaries of the material. Immediately or with 24 hours of writing your notes, reflect on the main concepts and takeaway points. Your note-taking section may be messy and your cue column may not convey a complete picture of the material, so use the summary area to organize your notes and identify the main themes or ideas. Summarizing helps you evaluate your understanding of the material as you go along, and it also provides an excellent resource for review when you’re studying for exams.

Manage your time.

Many college courses meet only two or three times per week, and you are expected to do much of your learning on your own time outside of the classroom. Time management is a key aspect of self-regulated learning (Wolters et al., 2017). The following suggestions may be helpful: End each day by planning your activities for the next day. Use a calendar (paper or electronic, whichever you prefer) to map out your responsibilities for each week, including the time that you need to spend studying and preparing for tests. To make major projects less intimidating, break them down into smaller tasks that do not deplete all your energy. Reward yourself for achieving milestones or completing assignments (The College Board, 2011).

Focus. Whether you are researching, reading, studying, or writing, focus on the task at hand. Eliminate distractions by turning off the television, the streaming music service, and your mobile phone. Do not multitask, because research has shown that the human mind cannot effectively multitask, despite many people’s beliefs that they are effective multitaskers (Sanbonmatsu et al., 2013; Willingham, 2010). One study of nonacademic distractions—such as folding laundry, watching videos, and texting—that people engaged in while attempting to learn online showed that the multitaskers received significantly lower test scores (Blasiman et al., 2018).

Manage your technology.

One study estimated that college students spend about 24 hours per week attending classes and studying—and almost as much time (21 hours per week) talking face to face, texting, talking on the phone, and using social network sites (T. L. Hanson et al., 2010). Several studies have linked excessive online activity, such as gaming and social networking, with lower grades, and one U.S. survey showed that 47 percent of the heaviest users of the internet were receiving mostly C grades or lower (S.-Y. Chen & Fu, 2008; Rideout et al., 2010; J. L. Walsh et al., 2013).

These studies do not prove that heavy internet use causes poor grades. That is, the studies show correlation rather than causation, an important distinction covered in Study Unit 2.8. However, it seems safe to suggest that turning off your cell phone while you are studying is a good idea. Or, if you are using your cell phone to study, turn off all unrelated apps and notifications (FIGURE 1.28).

FIGURE 1.28 Using Technology Wisely

This student is using technology as part of his learning, not as a distraction from his learning.

Stay motivated.

Attitude matters. One study reported that academic self-efficacy (organizational skills and attention to study), along with the ability to manage time and stress, are good predictors of grade point average (Chemers et al., 2001). Self-discipline, which involves showing up for class, is better than intelligence scores at predicting school performance, school attendance, and academic achievement (Duckworth et al., 2009; Duckworth & Seligman, 2017; Janosz, 2012; Krumrei-Mancuso et al., 2013). Although these studies show that self-discipline is related to course achievement, not that self-discipline causes courses achievement, much anecdotal evidence suggests that those who study hard and stay motivated perform better in college courses.

Find a study partner or join a study group. Group study can increase motivation and learning (J. A. McCabe & Lummis, 2018; Riel & Fulton, 2001). In addition, an excellent way to learn something is to teach it to someone else (Hoogerheide et al., 2019).

Learn as you go.

Use what you learn in Interactive Psychology: People in Perspective to help you manage stress (see Study Unit 10.18), improve your memory (see Study Unit 7.1), and stay healthy (see Study Unit 10.1).

To assess your study strengths and weaknesses, complete the metacognitive inventory in INTERACTIVE FIGURE 1.29.

Glossary

- metacognition

- An awareness and understanding of your own thought processes.