|

Table 1.1

Microbes and Human History

|

|

Date

|

Microbial Discovery

|

Discoverer(s)

|

|

Microbes Impact Human Culture without Detection

|

|

10,000 BCE

|

Food and drink are produced by microbial fermentation.

|

People of Africa and Asia

|

|

1500 BCE

|

Tuberculosis, polio, leprosy, and smallpox are evident in mummies and tomb art.

|

People of Africa and Asia

|

|

1000 CE

|

Smallpox immunization is accomplished by transfer of secreted material.

|

People of Africa and Asia

|

|

1025 CE

|

Quarantine was invented to prevent spread of disease.

|

Avicenna, or Ibn Sina (Persia)

|

|

1300–1400 CE

|

The Black Death (bubonic plague) kills 17 million people in Europe and Asia.

|

Saint Catherine of Siena nursed plague victims (Italy).

|

|

Early Microscopy and Microbial Disease

|

|

1676

|

Microbes are observed under a microscope.

|

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (Netherlands)

|

|

1717

|

Smallpox is prevented by inoculation of pox material, a rudimentary form of immunization.

|

Lady Montagu brought from Turkey to England, and Onesimus brought from Africa to New England

|

|

1765

|

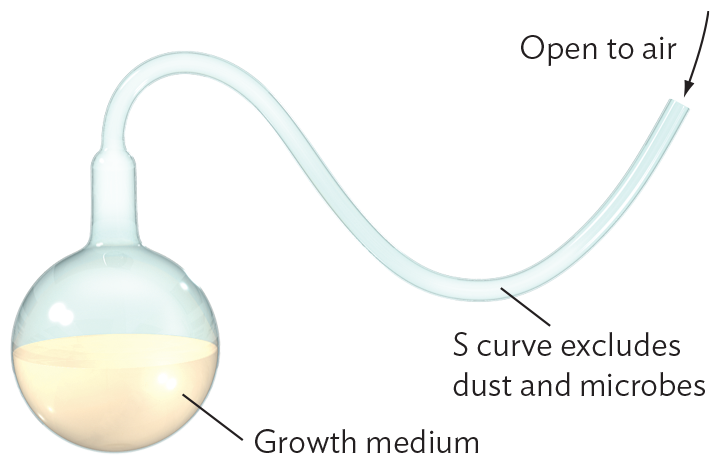

Microbes fail to grow after boiling in a sealed flask; evidence against spontaneous generation.

|

Lazzaro Spallanzani (Padua)

|

|

1798

|

Cowpox vaccination prevents smallpox.

|

Edward Jenner (England)

|

|

“Golden Age” of Microbiology as Science

|

|

1847–1867

|

Antisepsis prevents patient death during surgery and childbirth.

|

Ignaz Semmelweis (Hungary) and Joseph Lister (England)

|

|

1855–1867

|

Statistics show that poor sanitation leads to mortality (Crimean War).

|

Florence Nightingale (England)

|

|

1857–1881

|

Microbial fermentation produces lactic acid or alcohol. Microbes fail to appear spontaneously, even in the presence of oxygen. The first artificial vaccine is developed (against anthrax).

|

Louis Pasteur (France)

|

|

1877–1884

|

Bacteria are a causative agent in developing anthrax. The first pure isolate, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is cultured on a solid medium. Koch’s postulates demonstrate the microbial cause of diseases (anthrax and tuberculosis).

|

Robert Koch (Germany)

|

|

1884

|

Gram stain is devised to distinguish bacteria from human cells.

|

Hans Christian Gram (Denmark)

|

|

1889–1899

|

The concept of a virus is proposed to explain tobacco mosaic disease.

|

Martinus Beijerinck (Netherlands)

|

|

Biochemistry, Genetics, and Medicine

|

|

1900

|

Yellow fever is shown to be transmitted by mosquitoes.

|

Walter Reed (USA) and Carlos Finlay (Cuba)

|

|

1908

|

Antibiotic Salvarsan is synthesized to treat syphilis (chemotherapy).

|

Paul Ehrlich (USA) and Sahachirō Hata (Japan)

|

|

1911

|

Cancer in chickens can be caused by a virus.

|

Francis Peyton Rous (USA)

|

|

1918

|

Influenza A pandemic kills 50 million people worldwide.

|

Worldwide

|

|

1928

|

Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria are transformed by a genetic material from dead cells.

|

Frederick Griffith (England)

|

|

1929

|

Penicillin, the first widely successful antibiotic, is made by a fungus.

|

Alexander Fleming (Scotland), Howard Florey (Australia), and Ernst Chain (Germany)

|

|

1941

|

One gene encodes one enzyme in Neurospora (bread mold).

|

George Beadle and Edward Tatum (USA)

|

|

1941

|

Poliovirus is grown in human tissue culture.

|

John Enders, Thomas Weller, and Frederick Robbins (USA)

|

|

1944

|

DNA is the genetic material that transforms Streptococcus pneumoniae.

|

Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod, and Maclyn McCarty (USA)

|

|

1948

|

Protein structure of the alpha helix is discovered by X-ray crystallography.

|

Herman Branson, Linus Pauling, and Robert Corey (USA)

|

|

1952

|

DNA is injected into a cell by a bacteriophage.

|

Martha Chase and Alfred Hershey (USA)

|

|

Molecular Biology and Medicine

|

|

1953

|

The overall structure of DNA is a double helix, based on X-ray crystallography.

|

Rosalind Franklin and Raymond Gosling (England)

|

|

1953

|

Double-helical DNA consists of antiparallel chains connected by the hydrogen bonding of AT and GC base pairs.

|

James Watson (USA) and Francis Crick (England)

|

|

1961

|

Biochemical energy is stored in a proton gradient across the membrane of bacteria, mitochondria, and chloroplasts.

|

Peter Mitchell and Jennifer Moyle (England)

|

|

1968

|

Serial endosymbiosis explains the evolution of mitochondria and chloroplasts.

|

Lynn Margulis (USA)

|

|

1969

|

Retroviruses contain reverse transcriptase, which copies RNA to make DNA.

|

Howard Temin, David Baltimore, and Renato Dulbecco (USA)

|

|

1953–1971

|

Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) is developed for dehydration due to diarrhea and cholera, saving millions of lives.

|

Hemendra Chatterjee and Dilip Mahalanabis (India); Robert Phillips (USA)

|

|

1973

|

A recombinant DNA molecule is made in vitro (in a test tube).

|

Annie Chang, Stanley Cohen, Robert Helling, and Herbert Boyer (USA)

|

|

1977

|

A DNA sequencing method is invented and used to sequence the first genome of a virus.

|

Frederick Sanger, Walter Gilbert, and Allan Maxam (USA)

|

|

1977

|

Archaea are a third domain of life, the others being Bacteria and Eukaryotes.

|

Carl Woese (USA)

|

|

1979

|

Smallpox is declared eliminated—the culmination of worldwide efforts of immunology, molecular biology, and public health.

|

World Health Organization

|

|

Genomics and Medicine

|

|

1981

|

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) makes available large quantities of DNA.

|

Kary Mullis (USA)

|

|

1981–1983

|

AIDS pandemic begins (continues into present). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is discovered as the cause of AIDS.

|

Françoise Barré-Sinoussi and Luc Montagnier (France), Robert Gallo (USA), and others

|

|

1993

|

Gene therapy using a vector derived from HIV succeeds in treating severe combined immunodeficiency disorder (SCID).

|

Donald Kohn and others (USA)

|

|

1995

|

The first bacterial genome is sequenced: Haemophilus influenzae.

|

Craig Venter, Hamilton Smith, Claire Fraser, and others (USA)

|

|

1988–2013

|

Fecal microbiota transplant cures intestinal infections of drug-resistant Clostridioides difficile (CDI).

|

Thomas Borody and others (Australia and USA)

|

|

2014

|

Human Microbiome Project releases first compilation of microbes associated with healthy human bodies.

|

National Institutes of Health (USA)

|

|

2019

|

CRISPR gene editing is used to treat human patients for multiple myeloma, a cancer of white blood cells.

|

University of Pennsylvania

|

|

2019–2023

|

COVID-19 coronavirus is discovered and causes pandemic respiratory illness.

|

Li Wenliang (China)

|