SECTION OBJECTIVES

- Describe examples of how microbes contribute to natural ecosystems.

- Explain how mitochondria and chloroplasts evolved by endosymbiosis.

SECTION OBJECTIVES

How do microbes shape Earth’s environment? Koch’s growth of microbes in pure culture was a major technological advance that led to amazing revelations in microbial physiology and biochemistry. In hindsight, this discovery eclipsed the equally important study of microbial ecology. Microbes contribute vital ecological functions, cycling the many minerals essential for all life and filtering water for entire ecosystems (Figure 1.19). Just a tiny fraction of all microbial species can be cultured in the laboratory—the rest make up most of Earth’s entire biosphere, and only the outer skin of Earth supports complex multicellular organisms. These unseen microbial members of our ecosystems contribute vital functions such as nitrogen fixation. And the depths of Earth’s crust, to at least 2 miles down—as well as the atmosphere 10 miles out into the stratosphere—remain the habitat of microbes. So, for the most part, Earth’s ecology is microbial ecology.

A photo of a wetland in the Everglades. There is a region of dark murky water with lily pads floating on top, shrubs at the banks, a plain of grass in the background, and a blue cloudy sky above.

The first microbiologists to culture microbes in the laboratory selected the kinds of nutrients that feed humans, such as beef broth or potatoes. Some of Koch’s contemporaries, however, suspected that other kinds of microbes living in soil or wetlands existed on more exotic fare. Soil samples were known to oxidize hydrogen gas, and this activity was eliminated by treatment with heat or acid, suggesting microbial origin. Ammonia in sewage was oxidized to nitrate, and this process was eliminated by antibacterial treatment. These findings suggested the existence of microbes that “ate” hydrogen gas or ammonia instead of beef or potatoes, but no one could isolate these microbes in culture.

Among the first to study microbes in natural habitats was the Russian scientist Sergei Winogradsky (1856–1953). Winogradsky waded through marshes (wetlands) to discover new forms of microbes. In wetlands Winogradsky discovered microbes whose metabolism is very different from human digestion. For example, species of the bacterium Beggiatoa oxidize hydrogen sulfide (H2S) to sulfuric acid (H2SO4). Beggiatoa fixes carbon dioxide into biomass without consuming any organic food. Organisms that feed solely on inorganic materials such as iron or ammonia are known as lithotrophs. Today, wetland microbes are known for their critical roles in environmental quality (Figure 1.19). Wetland microbes support the food web of animals and plants, and they filter the groundwater that we eventually drink.

The lithotrophs that Winogradsky studied could not be cultured on Koch’s plate media containing agar or gelatin. The bacteria that Winogradsky isolated grew only on inorganic minerals. For example, nitrifiers convert ammonia to nitrate, forming a crucial part of the nitrogen cycle in natural ecosystems. Winogradsky cultured nitrifiers on a completely inorganic solution containing ammonia and silica gel, which supported no other kind of organism. This experiment was an early example of enrichment culture, the use of selective growth media that support certain classes of microbial metabolism while excluding others (discussed in Chapter 6). Enrichment culture is important in clinical microbiology labs to help identify the specific microbes that cause disease.

Winogradsky and later microbial ecologists showed that bacteria perform unique roles in the global interconversion of inorganic and organic forms of nitrogen, sulfur, phosphorus, and other minerals. Without these essential conversions (nutrient cycles), no plants or animals could live. Bacteria and archaea fix nitrogen (N2) by reducing it to ammonia (NH3), the form of nitrogen assimilated by plants. This process is called nitrogen fixation. Other bacterial species oxidize ammonium ions (NH4+) in several stages back to nitrogen gas. (Global cycles of nutrients are presented in Chapter 27.)

Within plant cells, certain bacteria fix nitrogen as partners of a host organism, a relationship called mutualism. Mutualism is a form of symbiosis, the growth of two species in intimate association; in mutualism, the partners receive essential benefits from each other. Bacteria that fix nitrogen in a mutualism within a plant cell are also called endosymbionts (meaning “inside symbionts”), organisms living inside a larger organism. Endosymbiotic bacteria provide nutrients to their host cell, which in turn provides protection and nutrients to the endosymbionts. Endosymbiotic bacteria known as rhizobia induce the roots of legumes (beans and lentils) to form special nodules to facilitate bacterial nitrogen fixation. Rhizobial endosymbiosis was first observed by Martinus Beijerinck.

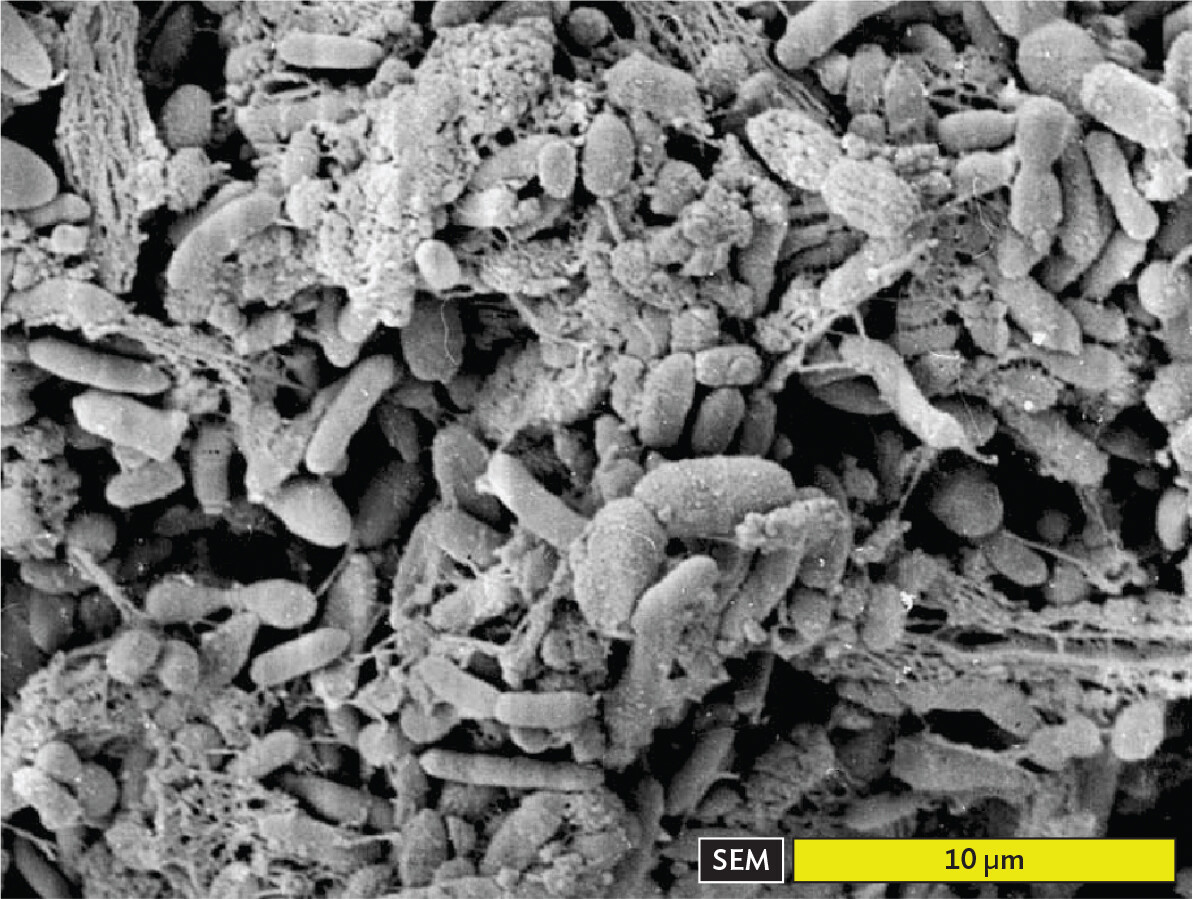

Communities of bacteria serve animals as digestive endosymbionts (Figure 1.20). Such a community is known as a digestive microbiome. Animals such as cattle and termites require a digestive microbiome to break down cellulose and other plant polymers. Even humans obtain as much as 15% of our nutrition from bacteria growing in our colon. Increasingly, the human digestive microbiome is considered an organ of the human body, with a role in medical conditions ranging from obesity to depression. Amazingly, bacteria from feces can actually cure a life-threatening disease. The transfer of fecal bacteria from one person to another, known as fecal microbiota transplant, was approved in 2013 by the FDA to treat infections of drug-resistant Clostridioides difficile (presented in Chapter 16 IMPACT).

A scanning electron micrograph of a biofilm with various digestive bacteria in the human intestine. The bacteria are packed tightly together. Some are thin and rod shaped, others are thick and spherical. Strands of partially digested food particles are visible among the bacterial cells. The cells are all 5 micrometers or less in maximum dimension. They cover a region greater than 30 micrometers in any direction.

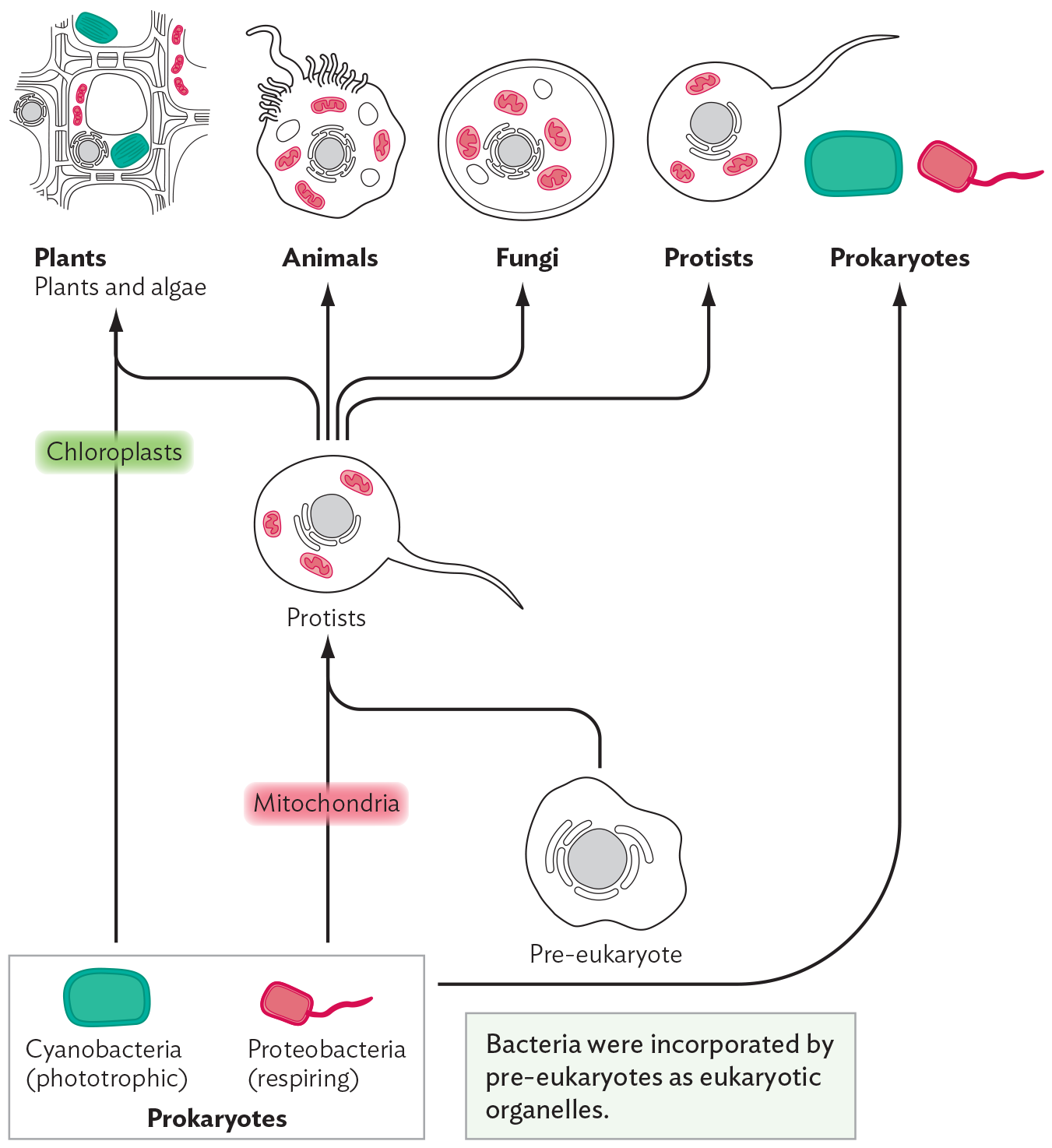

Microbial endosymbiosis, in many diverse forms, is widespread in all ecosystems. Many interesting cases involve animal or human hosts. The endosymbiotic origin of eukaryotic cells was proposed by Lynn Margulis (1938–2011), of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst (Figure 1.21). Margulis tried to explain how eukaryotic cells came to contain mitochondria and chloroplasts, membranous organelles that possess their own chromosomes. She proposed that eukaryotes evolved by merging with bacteria to form composite cells by intracellular endosymbiosis, in which one cell internalizes another that grows within it. The endosymbiosis may ultimately generate a single organism whose formerly independent members are now incapable of independent existence.

A flow chart demonstrating the five kingdom classification scheme, modified by endosymbiosis theory. There is a box labeled Prokaryotes, containing cyanobacteria, shown as an oblong green rectangle, and proteobacteria, shown as a smaller oblong rectangle in red with a tail. The cyanobacteria are labeled as phototrophic and the proteobacteria are labeled as respiring. An arrow labeled Chloroplasts points from Cyanobacteria to plants and algae, which are represented by a network of rectangular cells. An arrow labeled Mitochondria points from the proteobacteria to a circular cell with a tail labeled Protists. Near the prokaryotes, there is a pre eukaryotic cell. This cell is irregularly shaped and contains several organelles. A note reads, bacteria were incorporated by pre eukaryotes as eukaryotic organelles. There is an arrow pointing from Pre eukaryote to Protists as well. From Protists, arrows point to several groups. These groups are Plants and algae, Animals, Fungi, and Protists. Finally, there is an arrow pointing from the original box of Prokaryotes up to the top where Prokaryote is written next to the other groups.

A photo of Lynn Margulis. She is standing in a greenhouse filled with many tall, leafy green plants. Margulis is smiling at the camera. She has short dark brown hair. She is wearing a bright purple collared shirt.

Margulis proposed that early in the history of life, respiring bacteria similar to E. coli were engulfed by pre-eukaryotic cells, where they evolved into mitochondria, the eukaryote’s respiratory (energy-generating) organelle. Similarly, a phototroph related to cyanobacteria was taken up by a eukaryote, giving rise to the chloroplasts of phototrophic algae and plants. Ultimately, DNA sequence analysis produced compelling evidence of the bacterial origin of mitochondria and chloroplasts. Both these classes of organelles contain circular molecules of DNA, whose sequences show unmistakable homology (similarity) to those of modern bacteria. DNA sequences and other evidence established the common ancestry of mitochondria and respiring bacteria, and of chloroplasts and cyanobacteria.

The endosymbiotic origin of mitochondria has medical importance because mitochondria still share key properties with bacteria. Such properties include the structure and function of the respiratory complex. Mitochondrial defects cause human diseases, including a form of epilepsy associated with malformed muscle fibers (myoclonic epilepsy with ragged-red fibers, or MERRF). The similarity between mitochondria and bacteria also limits the use of certain antibiotics, such as those that kill bacteria by inhibiting respiratory proteins embedded in the membrane. Bacteria have the respiratory proteins in their cell membrane, whereas human mitochondria have similar proteins in the mitochondrial inner membrane.

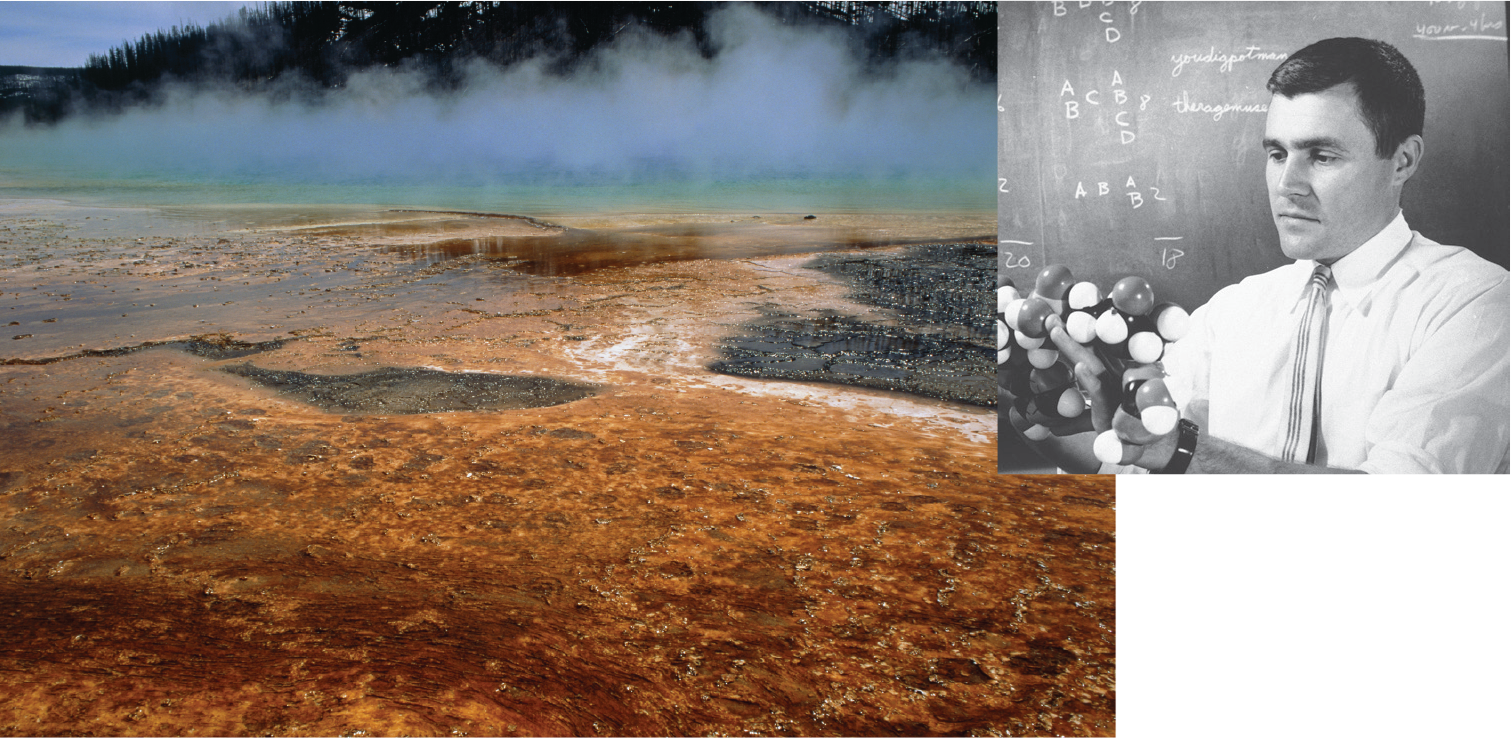

We continue to discover surprising new kinds of microbes deep underground and in places previously thought uninhabitable, such as the hot springs of Yellowstone National Park (Figure 1.22A). Microbes shape our biosphere and provide new tools that impact human society. For example, a bacterial DNA polymerase (a DNA-replicating enzyme) from a Yellowstone hot spring is used for the PCR technology that identifies pathogens in ill patients.

A photo of hot springs in Yellowstone National Park and a historic photo of Carl Woese. The first part is the photo of the hot springs. There is a shallow, steaming pool with a bright orange red floor. The second part is the photo of Woese. Woese is holding a ball and stick model of a complex molecule. He is dressed in a collared shirt and tie and has a contemplative expression on his face.

A. Yellowstone National Park hot springs contain archaea growing above 80°C (176°F) in water containing sulfuric acid. B. Carl Woese proposed that Archaea constitute a third domain of life.

In 1977, Carl Woese (1928–2012), of the University of Illinois (Figure 1.22B), discovered that some of the microbes from Yellowstone hot springs have genomes very different from those of all other known life forms. The genomes of these microbes had diverged so far from that of any known bacteria that the newly discovered prokaryotes were seen as a distinct form of life—the archaea (introduced in Section 1.1). Archaea living in extreme environments produce exceptionally sturdy enzymes that can be used for biotechnology.

SECTION SUMMARY

Thought Question 1.4 Suppose a microbiologist isolates microbes from 2 miles below Earth’s surface. Would these microbes be likely to cause disease in humans?

Microbes from deep in Earth’s crust would have evolved and adapted to conditions very different from those of the human body, such as the absence of oxygen and the scarcity of organic molecules. It is unlikely that such microbes could grow in a human body. Microbes that cause disease generally have evolved for many generations in intimate association with humans or with animals closely related to humans.