SECTION OBJECTIVES

- Describe the structure of the fungal mycelium.

- Explain how fungi contribute to ecosystems.

- Describe how different types of fungi and microsporidians cause disease.

SECTION OBJECTIVES

How do fungi contribute to our ecosystems? Fungi are heterotrophs that catabolize (break down and oxidize) complex molecules from other organisms. They break down wood and leaves, including substances such as lignin that animals cannot digest. Many fungi are saprophytes (heterotrophs that live on dead organisms). They decompose plant detritus, recycling nutrients for other plants. Underground, fungal filaments called mycorrhizae (singular, mycorrhiza) extend the root systems of trees, forming a nutritional “internet” that interconnects plant communities. Mycorrhizae could have inspired the fictional underground tree network shown in the 2009 film Avatar.

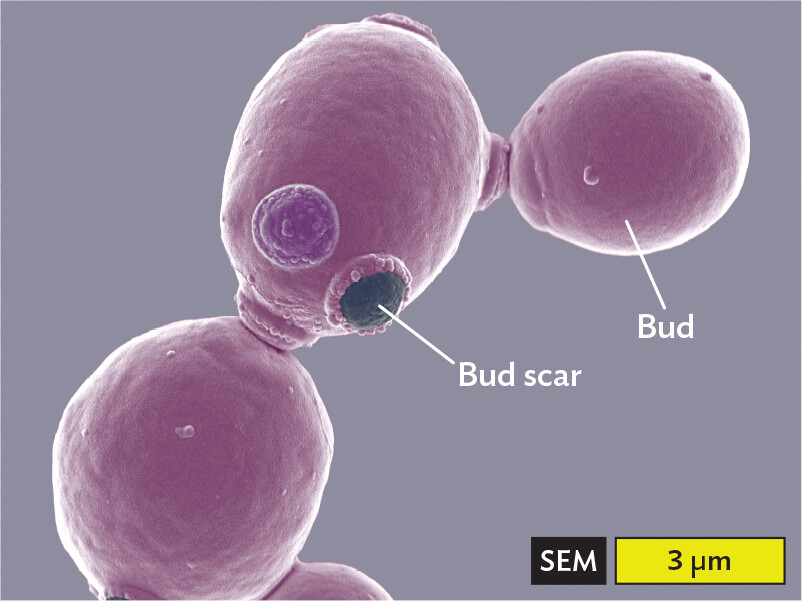

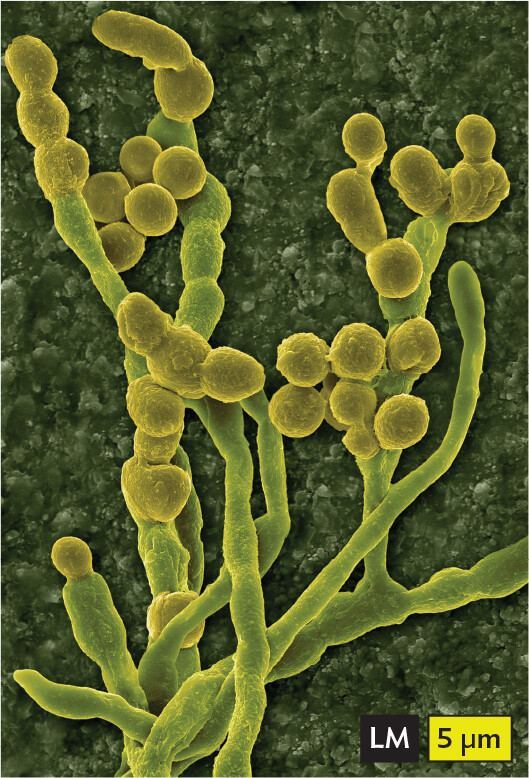

At the same time, some fungi are pathogens that threaten the lives of humans, animals, and plants. The yeast Candida albicans (Figure 11.4) is normally carried by most people, but it can kill a susceptible patient. The related yeast Candida auris is a deadly pathogen spreading in hospitals. C. auris is resistant to nearly all antifungal agents, and infected patients have a mortality rate of 35%.

A scanning electron micrograph of the structure of Candida albicans, a unicellular fungus. The micrograph shows three sphere shaped structures bridged together by small thick ring like structures. One of the sphere shaped structures on the top is smaller and has branched off of the sphere before it. It is labeled as the bud. On the surface of the sphere from which the bud came, there are two slightly elevated circular spots. One is purple and one is black. The black one is labeled bud scar. The size of the spheres and bud scar is approximately 3.5 and 1 micrometers, respectively.

Single-celled fungi are known as yeasts. Yeasts have the advantage of rapid growth and dispersal in aqueous environments. Many different single-celled yeasts evolved independently in different fungal taxa. Baker’s yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is used to leaven bread and to brew wine and beer. Other yeasts, such as Candida albicans, are important members of human vaginal biota. But C. albicans is also an opportunistic pathogen, causing vaginal infections as well as infections such as thrush in the mouth of patients with AIDS. Other yeasts that are opportunistic pathogens, commonly infecting AIDS patients, include Pneumocystis jirovecii, a yeast-form ascomycete; and Cryptococcus neoformans, a yeast-form basidiomycete.

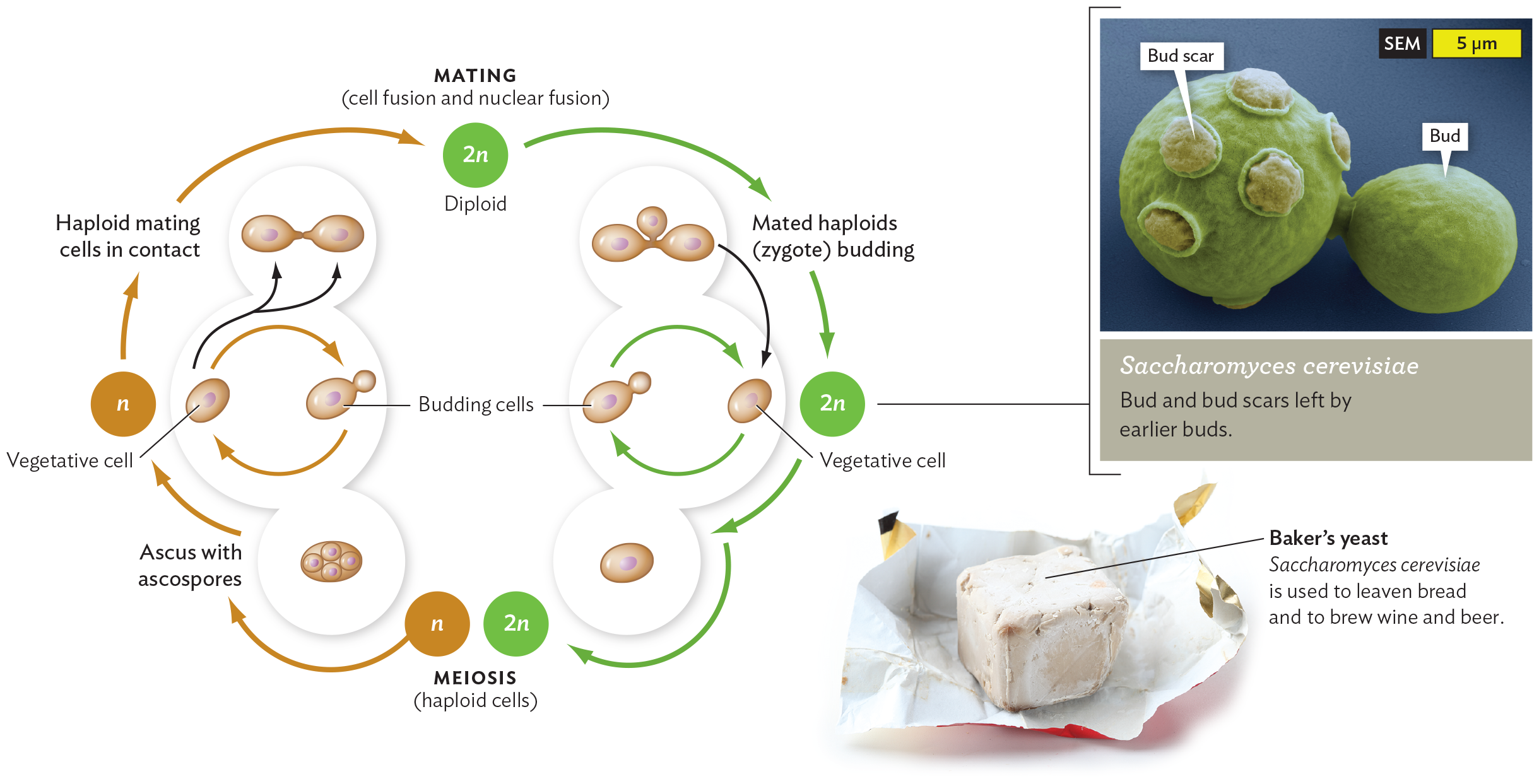

Some yeasts are asexual, whereas others, such as S. cerevisiae, undergo alternation of generations between diploid (2n) and haploid (n) forms (Figure 11.5). For S. cerevisiae, both haploid and diploid forms are single cells. The haploid (n) cells undergo several generations of mitosis and budding. This asexual reproduction is referred to as vegetative growth.

A diagram of the lifecycle of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, with an inset micrograph and photo. The diagram starts in the two N diploid stage, mating occurs via cell fusion and nuclear fusion. Mating results in mated haploids and zygote budding. An illustration shows two equal sized sphere shaped cells that are connected through a tubular like formation. A small sphere buds from the middle of the tubular formation. The mated haploids enter the 2 n stage. In this stage, the two equal sized sphere shaped cells separate from each other. One cell contains the attached bud, it is called the budding cell. The other cell is called the vegetative cell. These cycle between budding and vegetative states. Eventually, a single cell leaves this cycle and enters meiosis at 2 N. Meiosis generates haploid cells, designated n. An illustration shows an Ascus with ascospores. The ascus appears as a cell with four small cells inside. Each of the small cells has a nucleus. An arrow points to the next 1 n stage. In the second stage, there is one sphere shaped cell with a small bud sphere shaped structure as the budding cell and another sphere shaped cell as the vegetative cell. The cells cycle between budding and vegetative states. Eventually, the vegetative cell leaves the cycle and becomes two cells connected by a tubular structure. This represents haploid mating cells in contact. The haploid mating cells enter the 2 N, diploid mating process to start the lifecycle again. There is an inset micrograph of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae 2 N budding cell. The cell is spherical and is attached to an ovoid bud by a tubular structure. Circular bud scars cover the surface of the spherical cell. There is an inset photo of a cube of bakers yeast. It has a clay like texture.

At some point, however, various stress conditions, such as nutrient limitation, may lead the haploid cells to develop into gametes. The gametes are of two mating types. Cells of the two mating types may fertilize each other by fusing together and combining their nuclei to make a diploid (2n) zygote. The diploid cell—like the haploid cell—may undergo vegetative budding and reproduction. Under stress, however, a 2n cell may undergo meiosis, regenerating haploid cells. The haploid progeny possess chromosomes reassorted and recombined from those of their “parental” gametes.

Some fungi, such as C. albicans, can grow either as yeast or as filamentous fungi, depending on the environment; these are known as dimorphic fungi. Another dimorphic fungal pathogen is Blastomyces dermatitidis, the cause of blastomycosis, a type of pneumonia. B. dermatitidis grows as a yeast within the infected lung, but in culture and in soil environments it forms multicellular filaments. Filamentous fungi are described next.

CASE HISTORY 11.1

Fungus Growing in the Lung

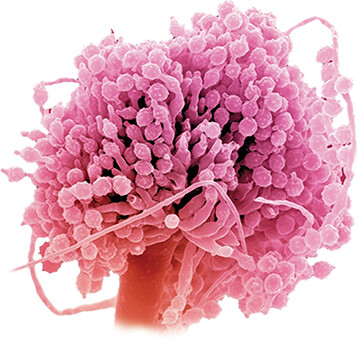

A scanning electron micrograph of Aspergillus. It is a stalk like structure with a bunch of tubules at the tip, each ending in small spherical shaped structures.

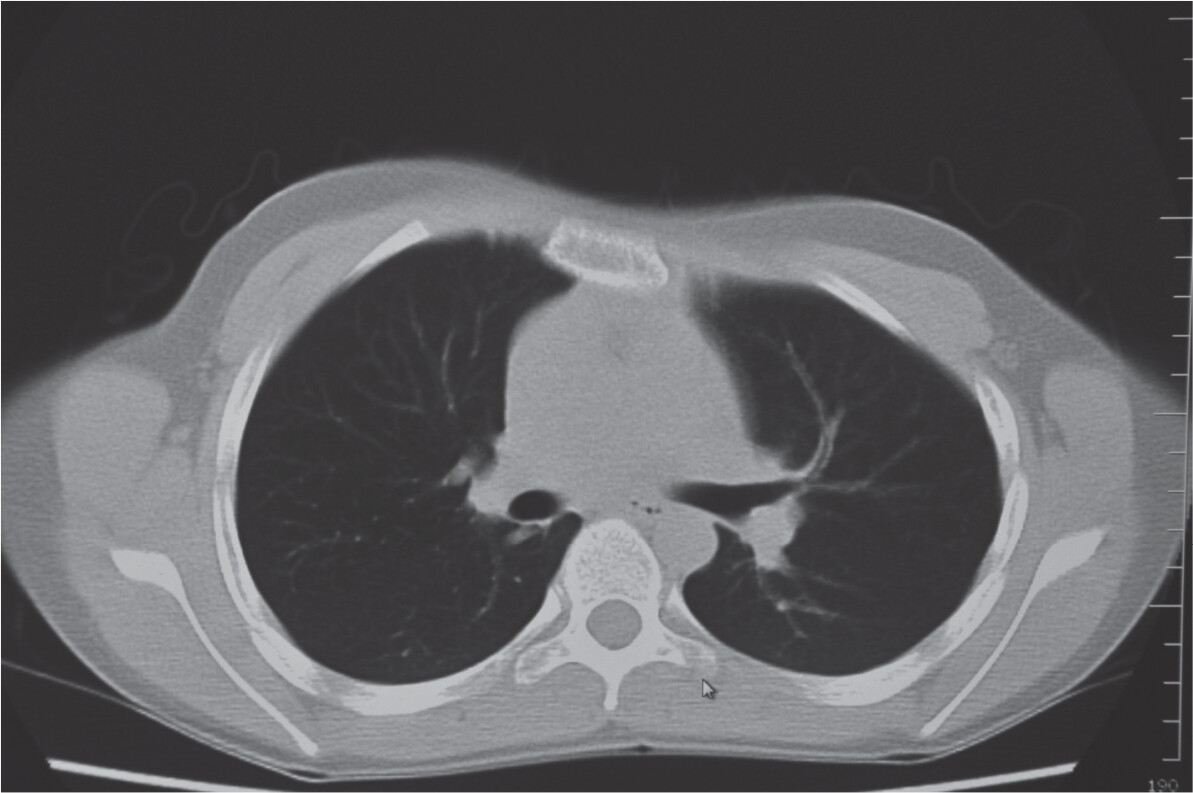

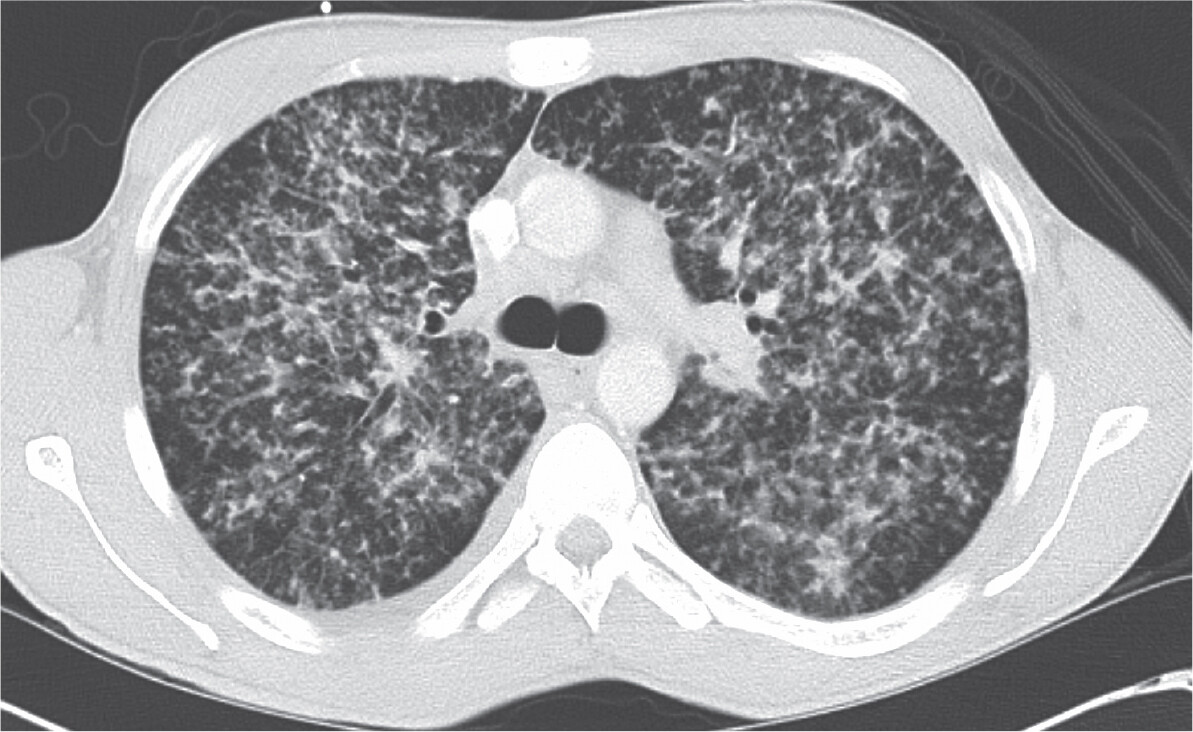

A photo of a chest C T scan of healthy lungs. The C T scan shows a top down view of the thoracic cavity. The heart can be seen in the center as an opaque gray oval. The lungs are to the left and right of the heart. They are mostly dark, indicating no obstructions. Thin, threadlike white lines pass through these spaces where the bronchi are located. Anterior to the heart is the sternum. Posterior to the heart is a vertebra of the spine. Thin rib bones are visible around the lungs. Fat, muscle and other tissue appears as opaque gray mass surrounding the previously described structures.

A photo of a chest C T scan of lungs infiltrated by Aspergillus mycelium. The C T scan shows a top down view of the thoracic cavity. The heart can be seen in the center as an opaque gray oval. The lungs are to the left and right of the heart. A web of white, fibrous like lines fill the lungs. These are the mycelia. Anterior to the heart is the sternum. Posterior to the heart is a vertebra of the spine. Thin rib bones are visible around the lungs. Fat, muscle and other tissue appears as opaque gray mass surrounding the previously described structures.

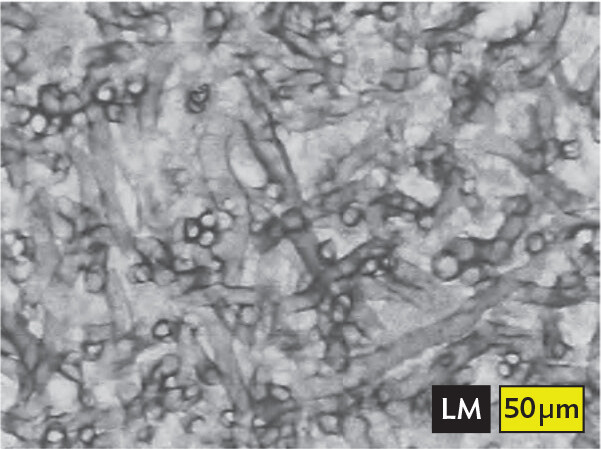

A light micrograph of Aspergillus mycelium invading the lungs. The micrograph shows numerous tubular structures ending with small circles. The size of one of the tubes is approximately 60 micrometers in length and 10 micrometers in width. The mycelia are packed tightly into the bronchi and alveoli of the lung.

Aspergillus is a filamentous fungus of the ascomycete group (see Table 11.2). Filaments of Aspergillus typically grow on soil or indoors on air conditioner coils or as basement mold. It forms spores that can reach significant concentrations in the air, where they are taken into the lungs and may cause allergic reactions. In patients with impaired immune function, Aspergillus spores may germinate and grow “fungus balls” that require surgical removal. The fungus is a common source of hospital-acquired (nosocomial) infection. In Frank’s case, however, the infection was community acquired. Frank’s predisposing conditions (depressed immune function due to diabetes and smoking) had allowed the fungal infection to take hold.

|

Table 11.2 Fungi |

|

|

Phylum and Genus |

Habitat or Disease |

|

Ascomycetes |

Form asci, pods of eight spores |

|

Aspergillus |

Breaks down plant detritus; infects lungs of immunocompromised patients |

|

Candida |

Yeast infections; thrush; opportunistic pathogen |

|

Penicillium |

Grows on bread and fruit; original source of penicillin |

|

Saccharomyces |

Ferments beer and bread dough |

|

Stachybotrys |

Black mold; contaminates dwellings |

|

Trichophyton |

Ringworm and athlete’s foot skin infections |

|

Basidiomycetes |

Mushrooms and mycorrhizae |

|

Amanita |

Extremely poisonous; produces alpha-amanitin toxin |

|

Lycoperdon |

Edible mushrooms |

|

Chytridiomycetes |

Motile zoospores with single flagellum |

|

Batrachochytrium |

Global disease of frogs |

|

Zygomycetes |

Saprophytes, insect pathogens, and mycorrhizae |

|

Rhizopus |

Bread mold; food production (tempeh) |

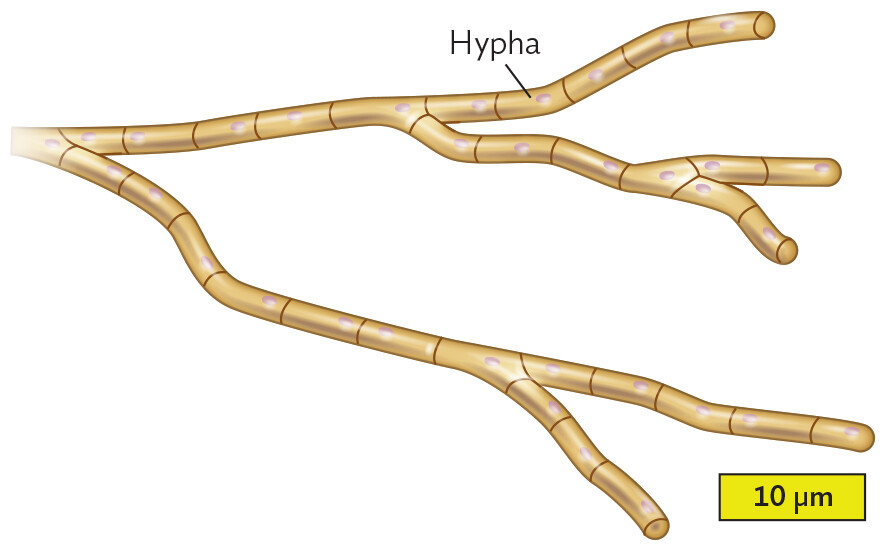

Many fungi grow as multicellular branched filaments called hyphae (singular, hypha; Figure 11.7A). The hyphae undergo a life cycle that produces spores for dissemination. Inhalation of fungal spores can lead to aspergillosis and histoplasmosis, conditions particularly dangerous for immunocompromised patients. Other fungi cause skin infections such as ringworm and athlete’s foot (medical term, tinea pedis). Examples of fungi commonly found in humans or in our environment are presented in Table 11.2.

A scanning electron micrograph of fungal mycelium. The micrograph shows numerous long tubular branch like structures tangled together. The width of the branches is approximately 1 to 3 micrometers.

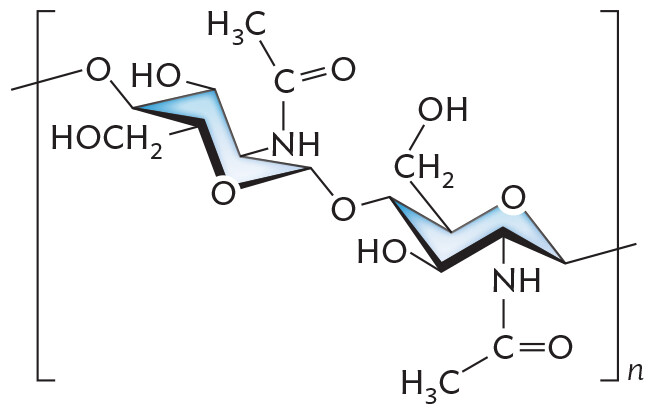

An illustration of the chemical structure of Chitin. The illustration is a chemical structure of Chitin consisting of polymers of N acetyl glucosamine. The single bond O molecule bonds the two hemiacetal ring structures at the fourth position.

An illustration of the structure of fungal hyphae. It shows a tubular structure branched into two with further subbranches. The tubes are labeled hyphae. The branches are segmented and each segment has a small sphere like structure present within. The width of the hypha is approximately 2 micrometers. The hypha extends more than 50 micrometers.

Hyphae have tough cell walls that are composed of chitin, an acetylated amino-polysaccharide stronger than steel (Figure 11.7B). Its strength derives from multiple hydrogen bonds between fibers. Hyphae grow by extending multinucleated cells (Figure 11.7C). As a fungal hypha extends, its nuclei divide mitotically without cell division. The hyphae form branching tufts called a mycelium (plural, mycelia). The mycelium may grow large enough to be seen as a fuzzy colony or puffball. As the hypha expands, its chitinous cell wall enables it to penetrate softer materials, such as plant or animal cells.

The biosynthesis of chitin provides a target for antifungal agents such as nikkomycin Z. Another drug target is the membrane lipid ergosterol, an analog of cholesterol not found in animals or plants. Ergosterol biosynthesis is inhibited by antifungal agents called triazoles.

The hyphal growth process means that most fungal forms are nonmotile. Fungi cannot ingest particulate food, as do protists. This is because their cell walls cannot part and re-form like the flexible pellicle of amebas and ciliates does (discussed next, in Section 11.3). Instead, fungi secrete digestive enzymes and then absorb the broken-down molecules from their environment. Fungi such as Aspergillus produce toxins (called mycotoxins) that contaminate food and harm human health. But fungi are so effective at secreting small molecules that they are engineered for biotechnology to make medical products; engineered Aspergillus is a billion-dollar industry.

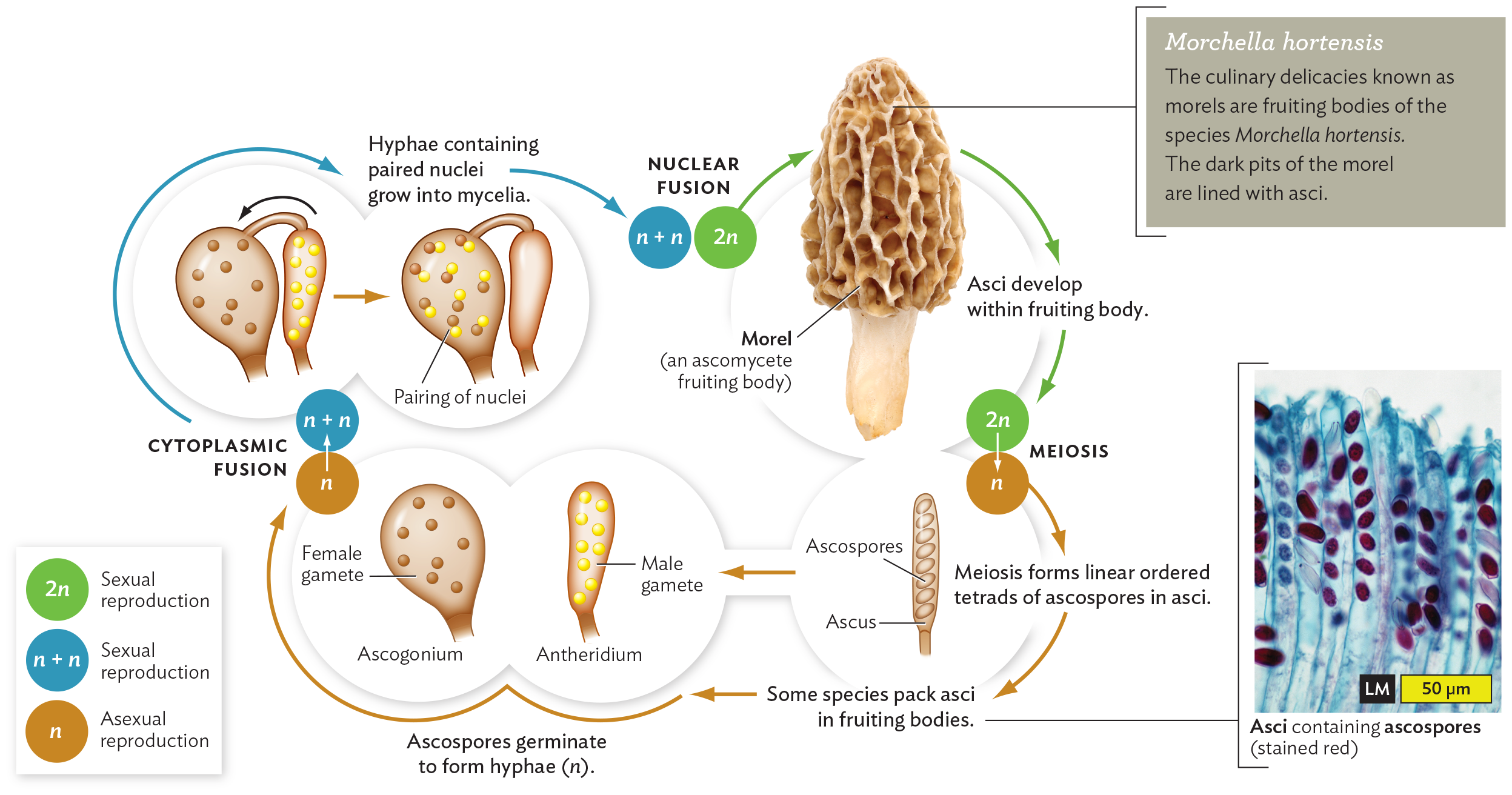

Filamentous fungi can expand at great length by asexual division (mitosis). Eventually, however, they run out of nutrients, and the cells undergo meiosis to form gametes. The gametes develop into spores for dispersal. An example of a spore-forming life cycle is that of ascomycete fungi such as Aspergillus or Morchella (Figure 11.8). In an ascomycete, the tips of the diploid mycelium undergo meiosis and develop into haploid ascospores within pods called asci (singular, ascus). The ascospores disperse until they germinate in a region of fresh resources. Each ascus undergoes cell divisions to form a haploid mycelium, which is male or female. The male and female structures fuse, followed by migration of all the male nuclei into the female structure. The paired nuclei then undergo several rounds of mitotic division while migrating into the growing mycelium. In the mycelial tips, the paired nuclei finally fuse (becoming 2n) and re-form a diploid mycelium. Overall, the diploid-haploid life cycle enables a fungus to respond genetically to environmental change by reassorting its genes through meiosis and fertilization. Gene reassortment provides new genotypes, some of which may increase survival in the changed environment.

A diagram of the lifecycle of an ascomycete with an inset photo of a morel mushroom and a micrograph of asci. The diagram is divided into three sections, 2n, n and n plus n. n describes asexual reproduction. The n section starts with an ascus containing ascospores. These are haploid structures. The caption reads, Meiosis forms linear ordered tetrads of ascospores in asci. An arrow pointing to the next stage reads, Some species pack asci in fruiting bodies. In the next stage, there is the Ascogonium and the antheridium. The Ascogonium contains small spherical structures showing the female gamete. The antheridium contains small spherical structures showing the male gamete. The caption reads, Ascospores germinate to form hyphae, n. The schematic now transitions from n to n plus n. This transition occurs via cytoplasmic fusion. n plus n describes sexual reproduction. In the next stage, cytoplasmic fusion occurs between the Ascogonium and antheridium through a tubular connecting structure. The male gametes are transferred into the Ascogonium. The nuclei pairing occurs inside the ascogonium. The caption reads, Hyphae containing paired nuclei grow into mycelia. The schematic now transitions from n plus n to 2 n via nuclear fusion. 2 n describes sexual reproduction. A thick stalk with a conical tip shows the diploid fruiting body, called an ascomycete. The conical tip contains dark pits and lines. This is a morel mushroom. The caption reads, Asci develop within the fruiting body. A second text box reads as follows. Morchella hortensis. The culinary delicacies known as morels are fruiting bodies of the species Morchella hortensis. The dark pits of the morel are lined with asci. The diploid, 2 n, state is converted to haploid, n, state through meiosis. There is an inset micrograph of asci containing ascospores. The asci are flattened tubes packed with oval structures that stain red. The oval structures are ascospores.

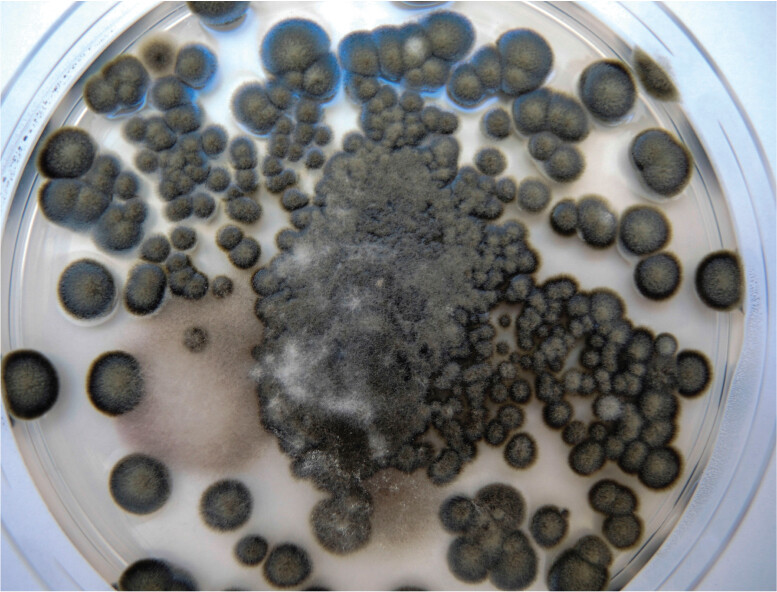

Some fungi pack their asci (or other spore-producing forms) into a larger structure called a fruiting body. Ascomycetes such as Aspergillus and Penicillium mold form relatively small fruiting bodies, called conidiophores, that disperse airborne spores. Conidiospore-forming ascomycetes are the major type of mold associated with dampness in human dwellings; they caused massive damage to homes flooded in the wake of Hurricane Katrina (see IMPACT).

A micrograph of the structure of mold. This species of mold consists of long tubular structures with circular tips at the ends. The tips are depressed in the center.

impact

Mold after Hurricane Katrina

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, much of the city of New Orleans was flooded. Entire neighborhoods were submerged for days or weeks. The flooding of homes full of drywall and organic materials made ideal conditions for the growth of “mold,” which generally consists of airborne ascomycete fungi. Mold grew not only on the materials submerged but also on the surfaces above, exposed to water-saturated air. Figure IMPACT 11.1 shows how mold grew up to 3 feet above the flood line (the highest level submerged) within the kitchen of a flooded home. Unfortunately, most homeowner insurance policies covered only damage “up to the flood line.”

A photo of a student pointing to mold on a wall. The student is wearing a mask and protective gloves. The student points to the lower flood line with one hand and to mold colonies on the wall above with the other hand. The flood line is a dark horizontal band of dried mud and debris that passes across the wall. Parallel lines of mud extend below the flood line. The mold colonies are many black cloudy circles that grow above the flood line.

Mold growing on damp surfaces releases spores into the air. Inhaled mold spores cause respiratory problems, even at relatively low levels (such as 2,000 spores per cubic meter). In New Orleans after the waters receded, the mold counts in the air inside homes reached as high as 650,000 spores per cubic meter. Such spore levels cause asthma attacks and hypersensitivity pneumonitis, a condition in which fever rises and the lungs fail. All remediation workers were advised to wear an N95 respirator mask. The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) found that even after all contaminated items—including furniture, carpets, and drywall down to the studs—had been removed from flooded homes, airborne spore counts still reached 70,000.

The most common types of mold found by the NRDC researchers were ascomycetes such as Cladosporium (Figure IMPACT 11.2). Cladosporium species form black or dark green colonies of conidia that readily break off and become airborne. Other ascomycetes found at high levels included Aspergillus and Penicillium species. These organisms occur at low levels even in clean air. Their spores cause allergy attacks and infect immunocompromised individuals. Some ascomycete molds produce mycotoxins, fungal toxins that cause long-term health problems. In addition, some flooded homes showed significant levels of Stachybotrys species, known as “black mold,” a possible cause of neurological problems and immunosuppression. Once these molds establish growth, their eradication is a major challenge.

A light micrograph of Cladosporium cladosporioides. The light micrograph shows branching tubes, the hyphae, with small spherical spore like structures at the end. The size of the spores and the width of the hypha are approximately 4 and 2 micrometers, respectively.

A photo of Cladosporium mold growing on a petri plate. Numerous black circular structures are found all around the Petri dish. They grow up off of the petri plate, forming dome shapes and they form a mound in the middle that has some white wisps at the top. There are some thin light gray spongy films on the plate too.

What can homeowners and communities do to decrease the incidence and prevalence of harmful airborne fungi?

The fruiting bodies of other ascomycete fungi can be impressively large and edible as prized foods. Morels (Morchella hortensis; see Figure 11.8) and truffles (Tuber aestivum) form large, mushroom-like fruiting bodies whose ascospores are dispersed by animals attracted by their delicious flavor. The famous truffles grow underground, where human collectors traditionally use muzzled pigs to detect and unearth them.

SECTION SUMMARY

Thought Question 11.1 For a fungus, what are the advantages of growing a mycelium? What are the advantages of growing as a single-celled yeast?

Mycelial growth enables coordinated expansion into a food resource, such as a host tissue. The large size of the mycelium enables the fungus to avoid being engulfed by amebas or host macrophages. Single-celled yeasts, however, can disperse readily to new habitats, finding new resources to exploit.