SECTION OBJECTIVES

- Explain the environmental significance of algae and their relatedness to plants.

- Describe the environmental role and health hazards of dinoflagellates.

SECTION OBJECTIVES

How do algae affect our health and environment? Eukaryotic microbes flourish in soil and water habitats, where they enrich the food web as producers and consumers. Major photosynthetic producers are the algae, especially the green algae (Figure 11.18). In freshwater and marine ecology, the algae, together with photosynthetic bacteria (cyanobacteria), are known as phytoplankton (discussed in Chapter 27). Algae and photosynthetic bacteria form the fundamental base of Earth’s food chain for all living things. They fix most of Earth’s carbon and produce most of the oxygen we breathe.

A light micrograph of a Volvox colony. The micrograph shows a large white translucent spherical structure, which comprises the Volvox colony. The diameter of the large sphere is approximately 300 micrometers. The colony is filled with numerous smaller green spherical structures that are about 70 micrometers in diameter. These are the progeny colonies.

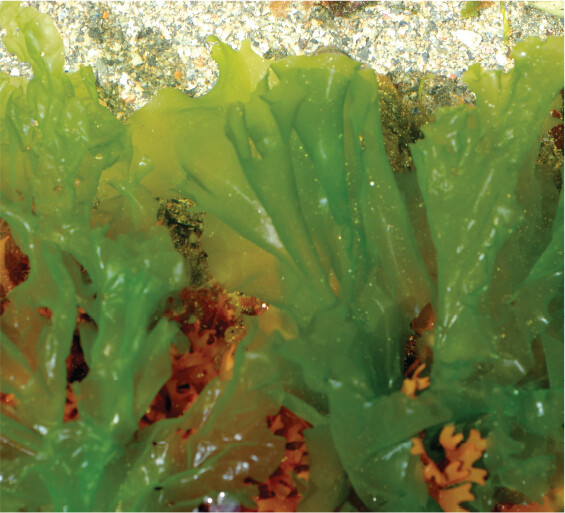

A photo of calcified stalks of Cymopolia. The photo shows shiny green crinkly vertical sheets. They consist of narrow stalks that flatten into broad, irregularly shaped sheets at their tops.

Algae are protists that conduct photosynthesis by using chloroplasts. Chloroplasts evolved from an ingested phototroph (the ancestor of modern cyanobacteria) by the process of endosymbiosis. An ancient proto-alga engulfed a photosynthetic cyanobacterium, perhaps with the aim of digesting it. But instead of being digested, the cyanobacterium provided photosynthetic carbon and received nutrients and protection in return from its host cell. This past evolutionary event—in a common ancestor of all plants—is known as primary endosymbiosis. Eventually, the cyanobacteria evolved into algal chloroplasts, organelles with genomes and structure greatly diminished compared with the original cyanobacteria. Some ancient algae then evolved into multicellular plants. In soil and water ecosystems, algae are consumed by many heterotrophic protists, such as amebas (discussed in the previous section).

Note: Cyanobacteria that cause toxic blooms on lakes are sometimes incorrectly called “algae.” The so-called algal blooms on lakes usually consist of cyanobacteria.

Note: Cyanobacteria that cause toxic blooms on lakes are sometimes incorrectly called “algae.” The so-called algal blooms on lakes usually consist of cyanobacteria.

Green algae make up the group Chlorophyta. Like plants, they are autotrophs, growing entirely through photosynthesis and absorption of minerals. Many green algae are unicellular, such as Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, a unicellular chlorophyte that serves as an important model system for genetics. C. reinhardtii has a symmetrical pair of flagella—a common pattern for green and red algae. The alga swims forward by bending its flagella back toward the cell, as if doing the breaststroke. C. reinhardtii cells are mostly haploid (n), reproducing by asexual cell division. But when conditions change, the haploid algae mate to undergo meiosis and form gametes. The gametes swim away and fuse with others to form 2n zygotes, whose reassorted genes may improve fitness in the new environment. Thus, C. reinhardtii undergoes environment-triggered alternation between diploid (2n) and haploid (n) forms. This alternation of diploid and haploid forms is similar to that of some fungal yeasts (see Section 11.2).

Other chlorophytes develop more complex multicellular forms. Volvox forms hollow spherical colonies, like a geodesic dome (Figure 11.18A), composed of cells similar to those of Chlamydomonas. Spirogyra is a filamentous pond dweller known for its spiral chloroplasts. In marine water, Cymopolia forms relatively large, calcified stalks of cells (Figure 11.18B). Still other marine algae grow in undulating sheets, such as Ulva, the “sea lettuce” familiar to swimmers. Sheets of Ulva can extend over many square meters, although they are only two cells thick.

The second group of “true algae,” also derived from primary endosymbiosis, is the red algae, or Rhodophyta. Rhodophytes are colored red by the pigment phycoerythrin, which absorbs efficiently in the blue and green range that chlorophytes fail to absorb. Because the red algae absorb wavelengths missed by the green algae, they can colonize deeper marine habitats, below the green algal populations. The most famous red alga is Porphyra, which forms large sheets harvested for food. Originally devised in Japan, sheets of Porphyra are used as nori to wrap sushi.

The primary endosymbiosis event that gave rise to green and red algae was the uptake of a cyanobacterium that evolved into the chloroplast, as discussed above. Later kinds of algae evolved through secondary endosymbiosis, in which one of the “true algae” was engulfed and incorporated again, retaining the chloroplast. Different events of engulfment by different kinds of protists led to the evolution of different types of algae, such as dinoflagellates, sargassum, kelps, and diatoms. Algae derived from secondary endosymbiosis show “mixotrophic” nutrition, involving both photosynthesis and heterotrophy. For example, dinoflagellates are predators of smaller protists.

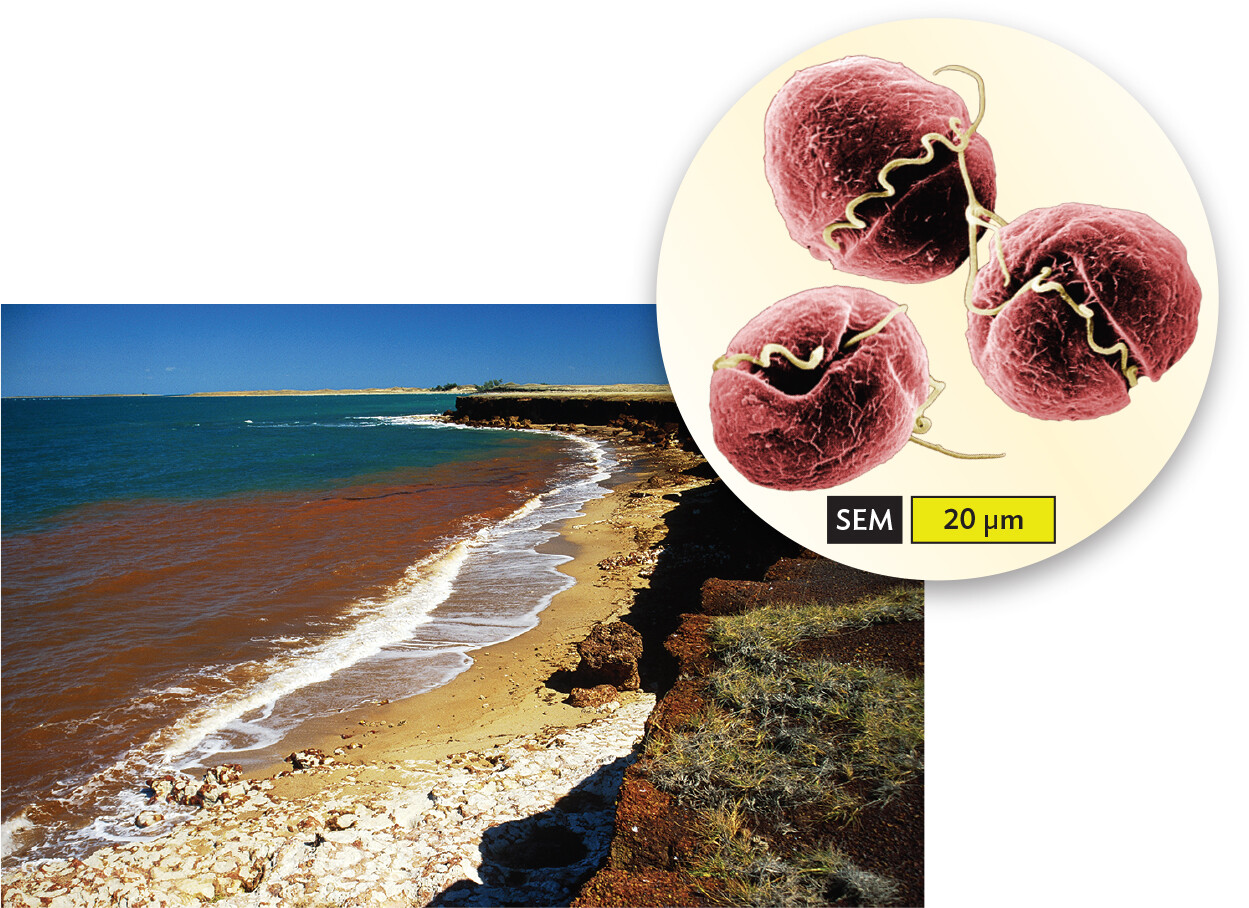

Dinoflagellates. The dinoflagellates are a major group of marine algae, essential to marine food chains (Figure 11.19A). Marine water may glow at night from Noctiluca, a dinoflagellate that exhibits bioluminescence. Other dinoflagellates make carotenoid pigments that are bright red. Blooms of red dinoflagellates such as Karenia brevis cause the famous red tide, which may have inspired the biblical story of the plague in which water turns to “blood” (Figure 11.19B). K. brevis releases neurotoxins that can be absorbed by shellfish, poisoning human consumers months or years later. In aquatic and coastal regions, such as the Chesapeake Bay, Pfiesteria dinoflagellates cause algal blooms and poison fish.

A scanning electron micrograph of Karenia dinoflagellates and a photo of a sandy beach with red tide. The first part is the micrograph. The cells are spherical and contain two flagella. One flagella wraps around the cell and the other floats freely behind the cell. The second part is the photo. The water is bright red near the shore. This discoloration is caused by a dinoflagellate bloom.

A. Karenia dinoflagellates. Each cell has one flagellum wrapped around it, whereas the other flagellum provides whiplike motion.B. “Red tide” caused by a bloom of dinoflagellates.

The armor-plated appearance of a dinoflagellate results from its stiff alveolar plates, composed of proteins or calcified polysaccharides. The complex outer cortex includes various toxin-emitting extrusomes and endocytic pores, as well as a species-specific pattern of alveolar plates. Like ciliates, dinoflagellates are highly motile, but instead of numerous short cilia, dinoflagellates possess just two long flagella, one of which wraps along a crevice encircling the cell (see Figure 11.19B). Like other secondary endosymbiont algae, dinoflagellates retain both the predatory ability of the second engulfing protist and the chloroplast derived from the ancestral alga—whose ancient ancestor engulfed a cyanobacterium that evolved into the chloroplast.

Certain dinoflagellates inhabit other organisms as mutualists, providing sugars from photosynthesis in exchange for a protected habitat. Their hosts include sponges, sea anemones, and, most important, reef-building corals. Coral endosymbionts, known as zooxanthellae, are vital to reef growth. The zooxanthellae are temperature sensitive, and their health is endangered by global warming. Rising temperatures in the ocean lead to coral bleaching (the expulsion of zooxanthellae), after which the coral dies.

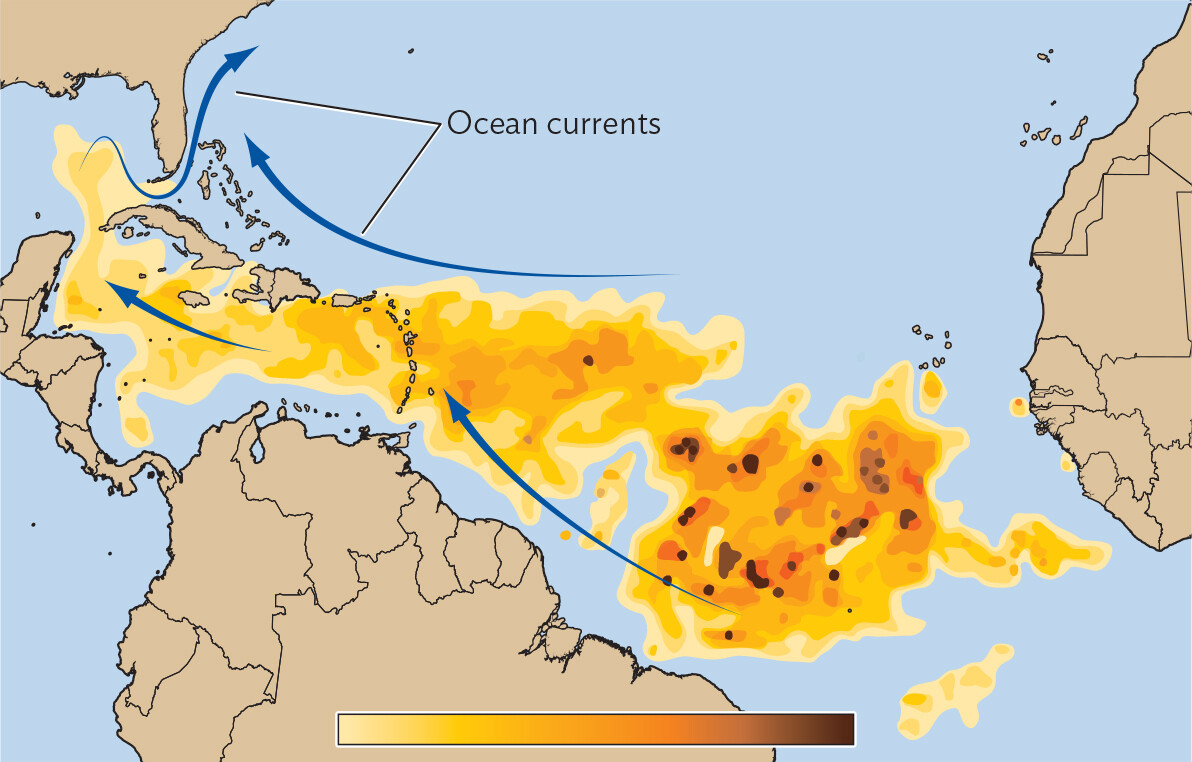

Sargassum. Other kinds of secondary endosymbiont algae are structured superficially like plants, including seaweeds such as kelps and Sargassum (Figure 11.20A). Sargassum grows stalks with leaflike blades and round gas bladders that keep the alga afloat, supporting a unique community of fish and invertebrates. It forms the basis of the Sargasso Sea, a region of the Atlantic Ocean bounded by currents that maintain a relatively intact mass of algae. But while Sargassum supports an important ecosystem, climate change has led to its overgrowth in other parts of the Atlantic (Figure 11.20B). Since 2011, Sargassum has increasingly disrupted beaches in Florida and the Caribbean, as in the great “blob” of 2023 that filled the Gulf of Mexico. Sargassum overgrowth results from warming ocean waters combined with nutrient-rich pollution.

A photo of Sargassum natans in the Sargasso sea. The brown algae Sargassum is a bush like structure with small flattened oval leaf like blades all around the branches. The algae has round gas bladders. It floats near the surface of the water. There is a small turtle swimming above the Sargassum.

A map of the Sargassum blob in the waters off the coasts of Florida, Mexico and northeastern South America. The blob extends from the Atlantic Ocean between South America and Africa to the Gulf of Mexico, following the direction of ocean currents. The blob is most dense in the Atlantic Ocean. There are fewer Sargassum in the blob once it reaches the Gulf of Mexico.

SECTION SUMMARY