SECTION OBJECTIVES

- Describe the parasitic cycles of worms, including roundworms, flukes, and tapeworms.

- Describe the parasitic cycles of arthropods, including ticks, mites, and bloodsucking insects.

SECTION OBJECTIVES

What kinds of parasites are actually multicellular animals? Many invertebrate animals are small enough to require a microscope to see; however, they evolved from animals and possess all the major organ systems of animals, such as a nervous system and digestive tract. Invertebrates such as insects and nematode worms are essential to the food webs of soil and ocean. An example is the worm Caenorhabditis elegans (Figure 11.21). At the same time, certain kinds of invertebrate animals are parasites, primarily worms and arthropods. Some grow much larger than microbes, although their infection cycles resemble those of microbial pathogens.

A light micrograph of the free living nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. The micrograph shows a long C shaped organism with tapered ends, one more tapered than the other. It has green splotches within. It also has clear pill shaped structures inside. The length and width at the center of the nematode are approximately 550 and 40 micrometers, respectively.

Invertebrate parasites, like the protozoan parasites discussed earlier, commonly cycle through more than one host, such as human and insect or human and domestic animal. Typically there is a definitive host (where sexual reproduction occurs) and an intermediate host (asexual reproduction only). In some cases, the human or animal may be an incidental host—that is, a host in which the parasite may grow and cause serious morbidity but cannot be transmitted to other hosts.

Worms are multicellular animals that possess fully differentiated organs. Although they are invertebrates, their body plans have surprising complexity, in some cases comparable to that of vertebrates. The free-living soil nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (Figure 11.21) serves as a major model system for the study of human development. The entire genome of C. elegans has been mapped, and many of the worm’s genes have homologs in the human genome that are involved in vital processes related to neural development, aging, and cancer.

Parasitic worms are called helminths. Helminths are wormlike invertebrates that do not share a unique clade (taxonomic group sharing a common ancestor). While most worms are nonparasitic and provide important ecosystem functions (such as that of earthworms), the parasitic worms cause a tremendous global burden of morbidity and mortality. In developed countries, humans can usually avoid parasitic worms by practicing good hygiene (washing hands) and wearing shoes, but once a person is infected, the parasite may be hard to eliminate.

Helminths include three categories:

Nematodes. Nematodes are diverse animals, with species adapted to all kinds of ecosystems; about half the known species are free-living. One nematode species—dubbed “the worm from hell”—was identified in a gold mine more than 3 km below Earth’s surface, where the temperature reaches 48°C (118°F). These worms graze on biofilms of bacteria indigenous to the mine.

Unfortunately, some species of nematodes are human parasites. Nematode parasites cause some of the most widespread and debilitating human infections worldwide.

CASE HISTORY 11.3

Dotty’s Itch

A micrograph of a pinworm. The pinworm has a C shaped structure with tapered ends and a darker part along the inside of the body. There is a section where the darker shape inside tapers off and then gets thick again before tapering completely.

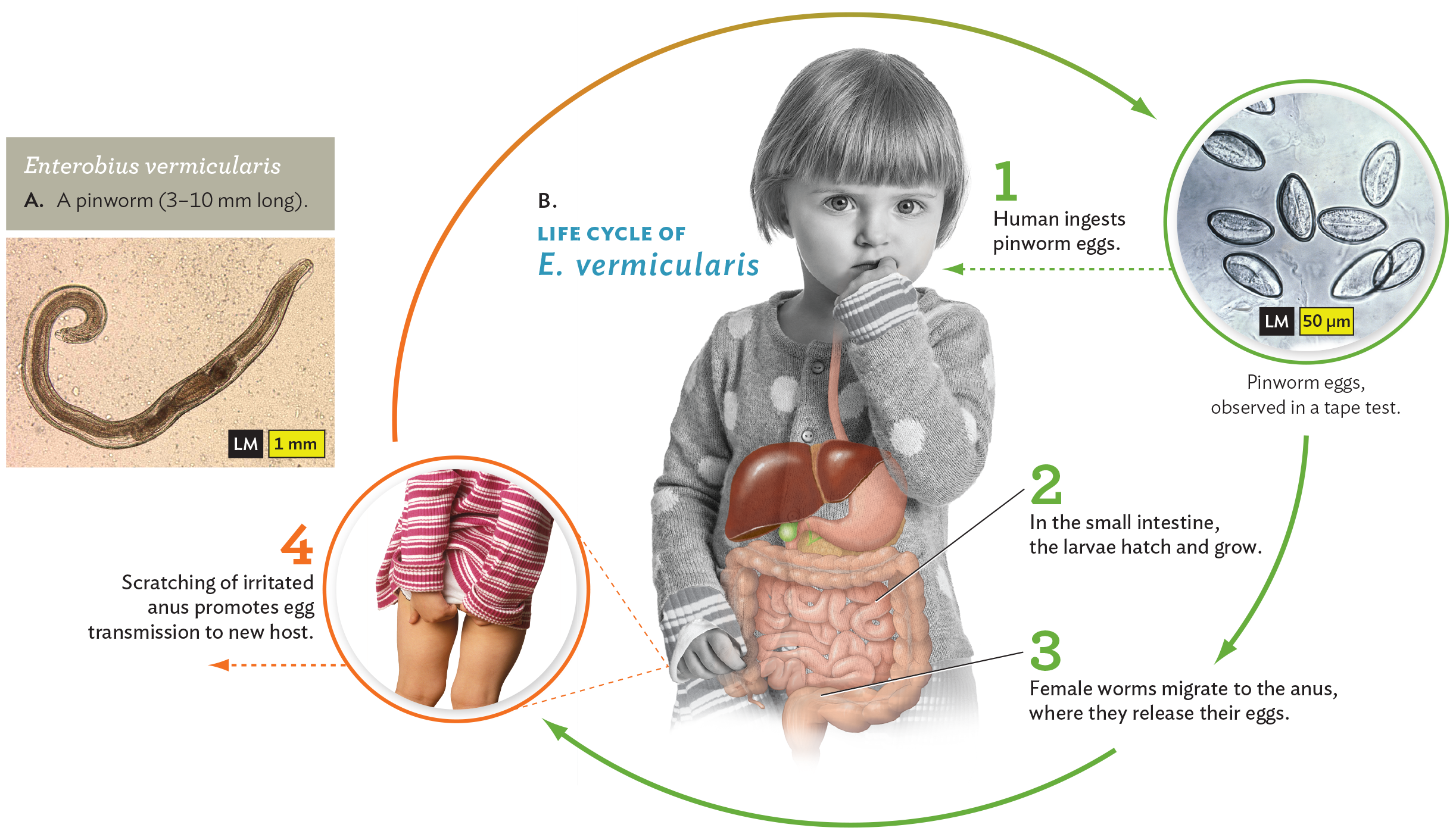

A light micrograph of Enterobius vermicularis and a diagram of its life cycle. The first part is the micrograph. E vermicularis, the pinworm, has a tube shaped cell body with one tapered end and one rounded end. The tapered end is curled into a C shape. The second part is the diagram of the pinworm life cycle. In step 1, a human ingests pinworm eggs. This is shown via an example photo of a child putting their fingers in their mouth. An inset light micrograph shows pinworm eggs observed in a tape test. In step 2, the pinworm larvae hatch and grow in the small intestine. In step 3, female worms migrate to the anus, where they release their eggs. This causes anal irritation and discomfort, shown via a photo of a person holding their buttocks in pain. In step 4, scratching of the irritated anus promotes egg transmission to a new host. This leads to the ingestion of eggs by a human, starting the cycle again.

Pinworms are small, white nematodes of the species Enterobius vermicularis. They infect only humans and are the most prevalent helminth infection in the United States and Europe, possibly infecting 25%–50% of the population. Children commonly ingest pinworms by sucking dirty fingers. Eggs can also be ingested from airborne dust. In the small intestine, the larvae hatch and grow, absorbing nutrition from the host. Usually, larval growth is unnoticed unless there is an exceptionally large number of worms. The female worms migrate to the anus, where they release their eggs. The perianal (around the anus) movement of worms causes irritation, leading to scratching of the anus; in the process, the host’s fingernails pick up eggs for transfer elsewhere.

When left untreated, pinworms can lead to complications, such as malabsorption of nutrients and anorexia related to the host’s immune response. In addition, secondary bacterial infection may occur at the perianal site of scratching or at the vulva or other places where the worms may migrate by mistake. The eggs persist for several weeks outside and are transmitted easily by contact with hands or with contaminated bedding. They are also transmitted by sexual contact.

Because transmission occurs readily within a household, all family members must be treated. The drug mebendazole, a selective inhibitor of worm microtubule biosynthesis, is effective against a broad spectrum of nematodes, including roundworm (Ascaris), whipworm, threadworm, and hookworm.

Pinworms are exclusive to humans, but other nematodes infect domestic animals and can be transmitted to humans. The roundworm Toxocara infects 14% of people in the United States and is contracted mainly from dogs. Toxocariasis commonly lacks symptoms, but complications can occur, such as blindness. To avoid parasites, all dogs and cats should receive monthly medication.

Worms called hookworms (Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus) are common in the southern United States and in tropical regions around the world. Their cycle differs from that of pinworms. Unlike pinworms, hookworm larvae grow in the soil, feeding on soil microbes until they penetrate the host skin, often through the soles of bare feet. The hookworms travel through the blood until they penetrate the alveoli in the lungs and then are coughed up to the throat and ingested. Within the small intestine, the hookworms latch onto the intestinal lining and suck blood. Their offspring then exit in the feces. Large numbers of hookworms can cause anemia and protein insufficiency. Hookworm prevalence is the source of health disparities, with highest prevalence in impoverished communities (see Health Equity on page 343).

Another parasitic nematode is Trichinella spiralis, the cause of trichinosis. T. spiralis is named for the spiral-form cysts made by worm larvae embedded in muscle. The parasite may be transmitted to humans who eat raw or undercooked pork; this is why cooking directions traditionally specify that pork should be “well-done.” Bear meat and horse meat can also carry T. spiralis. Once ingested, the larvae mature in the intestinal mucosa, mate, and produce progeny larvae. The new larvae now encyst in the host muscles, where they may cause pain and eventually death. In recent years, trichinosis has become rare in industrial countries, but it remains a problem in developing countries.

In tropical regions, severely debilitating worm infections are caused by various kinds of tiny filarial worms that grow within the blood, lymph, or subcutaneous fatty tissues. Most species are transmitted by biting flies, although some are transmitted by aquatic arthropods. Once introduced by an insect, the filariae (singular, filaria) reproduce and multiply to enormous numbers throughout the host’s surface tissues. This large number of worms is necessary to ensure a high population within the tiny amount of blood meal taken by an insect, enabling transmission to the next host. For some species, such as Brugia malayi, the large numbers of worms in the lymphatic system may block the lymphatic ducts, leading to swelling of the body parts (a condition called elephantiasis). More will be said about elephantiasis in Chapter 21 (see Figure 21.28). Other filarial diseases include river blindness (Onchocerca volvulus), in which worm-induced corneal inflammation leads to blindness; and guinea worm disease (Dracunculus medinensis), in which worms form painful blisters on the skin until they are released outside into water.

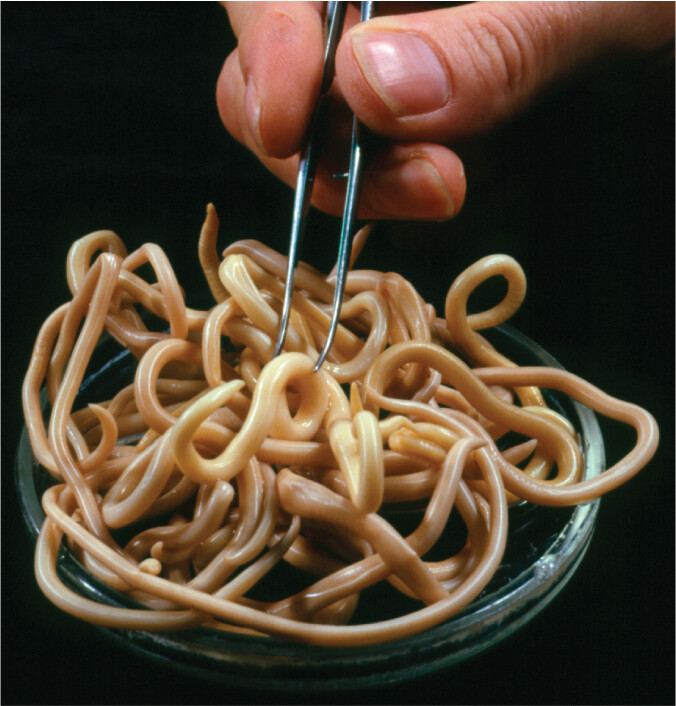

Roundworms such as Ascaris lumbricoides can grow to relatively large sizes within the human digestive tract, and their effects may be lethal (Figure 11.23). Ascaris worms cause infection by ingestion of eggs from soil. The worm eggs then develop into worms within the digestive tract, where they increase in size indefinitely and can obstruct the intestine. In some cases, worms may invade the lungs or other organs, causing life-threatening damage.

A photo of a pile of roundworms, Ascaris lumbricoides, on a Petri plate. Each roundworm has a long tubular structure. The worms are tangled together and twisted in all directions. One is being handled with sharp edged forceps.

Within the intestine, the worms produce eggs that exit the anus. Defecation outdoors in soil may lead to transmission to other people who unknowingly pick up the eggs on hands or feet. Roundworms infect a billion people worldwide, primarily in tropical areas, as well as the southern United States. Antihelminthic medications treat roundworms successfully when caught early, but the removal of larger worms may require surgical intervention.

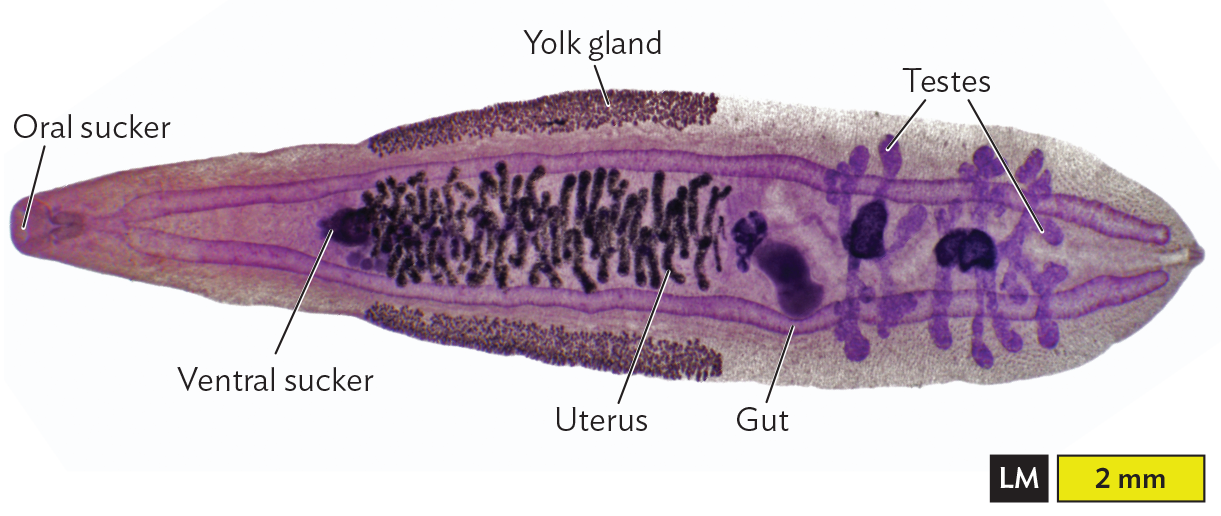

Trematodes. Trematodes (flukes) infect many kinds of animals, though most species require a mollusk as their primary host. Trematodes are flatworms (phylum Platyhelminthes). Like roundworms, they have an internalized mouth, “throat” (pharynx), and digestive tube, but the tube ends in one or more pouches called ceca (singular, cecum). Because the worm lacks an anus, it must expel its wastes back out the mouth. A fluke usually has two suckers—one near its mouth and one on the ventral side of the body. The mouth sucker ingests nutrients from the host.

Different fluke species preferentially attach to different internal organs, such as the liver, the lung, or the intestine. One example is the liver fluke, Clonorchis sinensis (Figure 11.24). The fluke arises from eggs ingested by a snail, where the larvae develop into a free-swimming form. The swimming larvae then penetrate the skin and flesh of a fish, where they develop into a secondary form. If the fish is raw or undercooked when ingested by a person, the parasite may attach to the person’s bile duct, where it grows and matures, producing eggs that exit through the bowel and anus. This fluke can grow to 2.5 cm; others can grow as long as several meters. Prolonged growth of the fluke is associated with secondary infections and predisposition to cancer.

A labeled light micrograph of the structure of the liver fluke, Clonorchis sinensis. The liver fluke is long horizontally with one tapered end. At the tapered end, the very tip is stained pink and there’s a little indent labeled oral sucker. A tubular structure connects the oral sucker to the ventral sucker, about 1 millimeter away in the direction of the organism’s interior. After the ventral sucker, closer to the center of the organism, there are many brown pill shapes clustered together. The uterus encloses this cluster of pill shaped structures. A thick band above and below the uterus is the yolk gland. Beyond the uterus is the gut and the testes. The gut is darker staining and consists of tubular structures. The terminal end of the body has two larger sac like structures with tubular branches coming off of them. These tube like structures are the testes. The liver fluke is about 5.5 millimeters long and 1.5 millimeters wide.

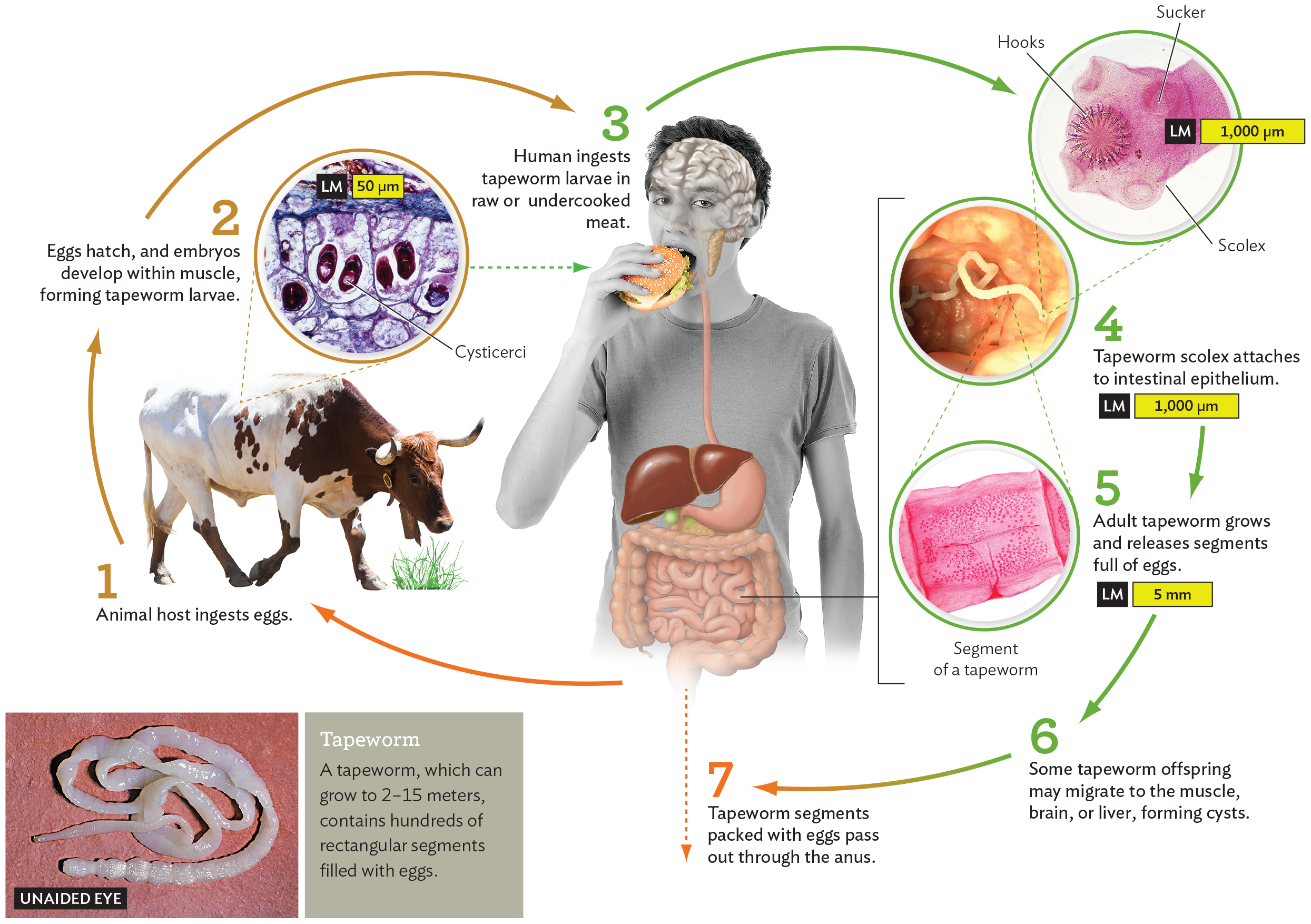

Cestodes. Tapeworms (cestodes) are transmitted through larvae embedded in uncooked meat. Different species are found in pork (Taenia solium), beef (Taenia saginata), and fish (Diphyllobothrium). Infection with fish tapeworms has historically been very common in regions of Asia and South America, where raw fish is routinely consumed. In the United States, the growing popularity of raw-fish dishes such as sushi and ceviche has led to an increase in the incidence of fish tapeworm infections.

Tapeworms are flatworms (Platyhelminthes), and their form is very different from that of both flukes and roundworms. The tapeworm is composed of a head and successive segments, which form out of the head and then are gradually pushed down in a tail that may grow 2–15 meters in length (Figure 11.25). The head of the tapeworm, called the scolex, has a special sucker device. Each segment of the tapeworm contains both male and female reproductive organs, which may fertilize each other or cross-fertilize with another segment. Tapeworm segments packed with ova (eggs) pass out through the anus of the host, where the segments appear like moving bits of rice. The segments fall to the ground, where some other host may ingest them. A tapeworm may grow for many years inside the digestive tract of a host without notice, until some of its offspring (larval form) migrate to the muscle, brain, or liver. In these internal organs, the tapeworm larvae may form cysts, leading to muscle pain and neurological symptoms such as seizures.

A diagram of the life cycle of a tapeworm. In step 1, an animal ingests tapeworm eggs. This is shown via an inset photo of a cow grazing. In step 2, the eggs hatch and embryos develop within muscle, forming tapeworm larvae. There is an inset micrograph showing cysticerci within muscle tissue. The cysticerci are oval shaped and stain darkly in comparison to the surrounding tissue. In step 3, a human ingests tapeworm larvae in raw or undercooked meat. This is shown via an inset photo of a person eating a hamburger. Illustrated organs are overlayed on the photo, including the brain, the parotid salivary glands, the esophagus, liver, stomach, gallbladder, small intestine and colon. In step 4, the tapeworm scolex attaches to intestinal epithelium. This is shown in an endoscopy photo of a tapeworm within an intestine. An inset micrograph shows the structure of a tapeworm scolex in greater detail. In step 5, an adult tapeworm grows and releases segments full of eggs. An inset micrograph shows a segment of a tapeworm containing many tiny eggs. In step 6, some tapeworm offspring may migrate to the muscle, brain, or liver, forming cysts. In step 7, tapeworm segments packed with eggs pass out through the anus. This sets the grounds for an animal host to ingest eggs, starting the cycle anew. To the side of the diagram, there is an inset photo of a tapeworm on a flat surface. It has a long, shiny tubular structure coiled into a pile. A caption reads, a tapeworm, which can grow to 2 to 15 meters, contains hundreds of rectangular segments filled with eggs.

From a global standpoint, parasitic worms cause substantial health problems, particularly for children, in whom malnutrition leads to stunted mental and physical development. At the same time, because worms are so prevalent, a hypothesis has been proposed that the human immune system evolved for optimal function in the presence of a modest number of helminths. This hypothesis is supported by the negative correlations observed between the prevalence of helminths and prevalence of autoimmune disorders such as asthma, eczema, and Crohn’s disease. Such diseases are common in urban areas with good hygiene but are rare in rural areas with poor hygiene and high worm prevalence. The hypothesis suggests that in the absence of helminths, components of the immune system that evolved to fight worms attack the body’s own tissues instead. The concept has led researchers to test the possibility that modest exposure to helminths may help prevent autoimmune disorders (discussed in Chapter 16). Although the hypothesis is unproven, it is being tested in clinical trials in which Crohn’s patients are exposed to pig parasites that stimulate the human immune system but cannot complete an infection cycle in humans.

Arthropods are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton and jointed appendages; the group includes insects and arachnids (spiders and mites). Many arthropods are free-living, but others are parasites with complex life cycles. Some arthropods are ectoparasites, attaching to the surface of a human or other vertebrate. Others are parasites that burrow into the flesh. Some arthropod parasites suck blood and then fall off, whereas others inject their eggs to develop for many weeks or months inside the host. As we saw for worms, arthropod parasites of humans may be acquired from the environment, or they may be highly infectious, acquired from other infected humans.

Arachnid parasites. Members of the arachnid group Acari are eight-legged mites and ticks. They include many species that are parasites of animals and plants throughout terrestrial habitats. Most people have Dermodex mites living in their hair follicles and facial pores.

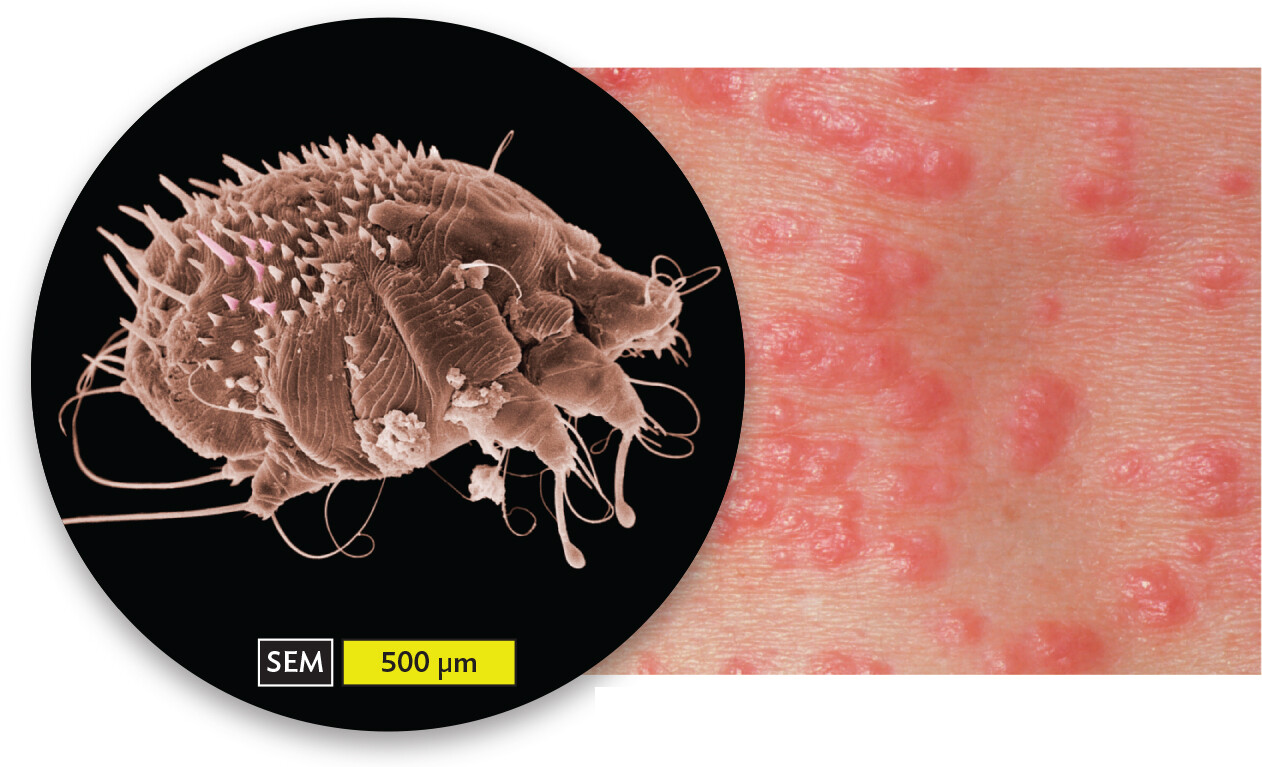

Certain types of mites cause mange (in animals) and scabies (in animals or humans), a condition also known as acariasis (Figure 11.26). Scabies in humans is caused most often by the “human itch mite,” Sarcoptes scabiei. The mites attach to the skin by suckers and then burrow under the skin by using special mouthparts and cutting surfaces on their forelegs. As the mites burrow into the skin, they lay eggs that hatch into larvae. The larvae come out of the skin to attach to a hair follicle, where they feed and molt until they reach the eight-legged adult stage; then they drop off to find new hosts. The movement of mites and larvae within the skin causes intense itching, as does the allergic reaction to the eggs. Itching and scratching lead to scabs, as well as hair loss.

A scanning electron micrograph of Sarcoptes scabiei variant hominis and a photo of a scabies rash. The first part is the micrograph. The Sarcoptes scabiei variant hominis mite has a rounded body structure. Legs project from the front and rear ends. The rear exterior and upper covering of the mite is covered in spiky protrusions. Thin, wispy strands extend from various parts of the mites body. The second part is a photo of the rash. The scabies rash presents as clusters of bright red, shiny bumps on the skin.

A. Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis, the mite that causes scabies in humans.B. The rash of scabies.

Mites are highly infectious; they are typically found at the wrists and other body parts that often come in contact with another person. Mites spread rapidly in groups of people in close quarters, such as a school dormitory or nursing home.

Ticks (order Ixodida) resemble mites in their eight-legged form, but they are larger and usually do not burrow completely in the skin. Ticks are ectoparasites that suck blood for nutrients to produce eggs and then fall off to disperse their progeny. Ticks often go unnoticed by their hosts, but they are vectors for many serious disease agents, including bacteria, protozoa, and viruses. The deer tick, Ixodes scapularis (Figure 11.27), is famous for carrying the spirochete of Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi. Once the tick attaches to the host, the spirochete slowly migrates from the tick’s digestive tract to its salivary gland and then into the host. Other ticks carry pathogens that cause anaplasmosis, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and tularemia.

A photo of an engorged deer tick on the skin. The deer tick has a spherical bead like body with three small pairs of legs on its ventral side. Its body is engorged to the point that it looks similar to an inflated balloon. The length of the tick is approximately 5 millimeters.

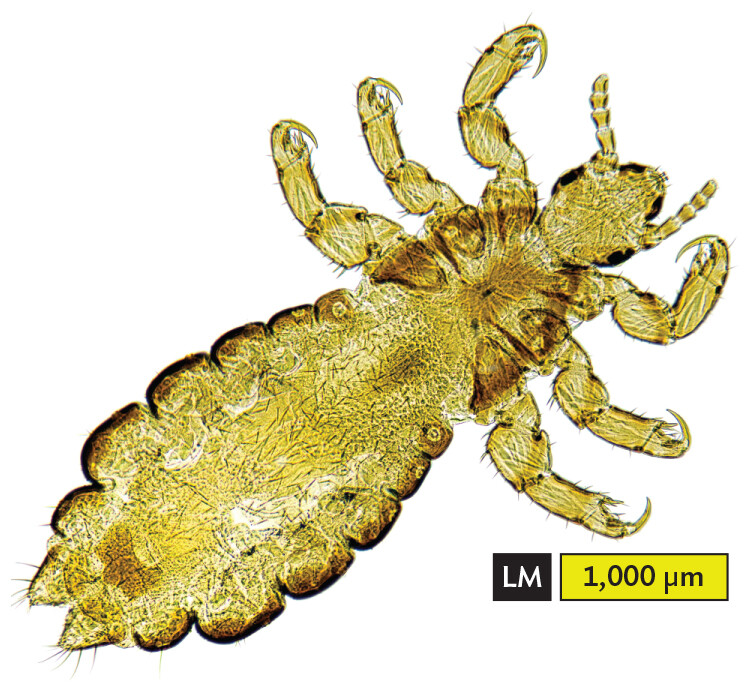

Insect parasites. Parasitic insects are six-legged, with or without wings. The most famous infectious parasitic insects are sucking lice (suborder Anoplura). Lice have been given many colorful names throughout history and were immortalized by Robert Burns in his poem “To a Louse.”

Sucking lice are wingless ectoparasites that suck blood and then produce eggs (Figure 11.28). Lice tend to be highly specific to one host species, and different body sites are preferred by different louse species, such as head lice, body lice, and pubic lice (sexually transmitted). Head lice attach their eggs to a hair. Despite good hygiene, head lice spread readily among people in close quarters, such as schools and army barracks; lice are difficult to eliminate because the eggs are attached firmly and are not killed by normal shampoos, requiring special medication. Body lice lay their eggs in hair or clothing. Pubic lice, Pthirus pubis, commonly called “crabs,” specifically infect the pubic hair. To a lesser extent, pubic lice infect the hair of eyebrows, eyelashes, and armpits. Their transmission is usually through sexual contact (although the dismayed sexual partner is sometimes assured that it “could have been the eyebrows”).

A light micrograph of a head louse. The louse has a transparent structure with three distinct parts, the head, the thorax and the abdomen. The small head has two antennae structures pointing out from it. The thorax connects the head and the abdomen. Three pairs of legs extend from the thorax. The segmented abdomen is an elongated ovoid shape. The length of the head louse is approximately 3500 micrometers in total.

A scanning electron micrograph of head lice on hair. The micrograph shows two lice each holding on to the hair strands using their legs. There are three parts to their bodies, the head, the thorax and the abdomen. The abdomen is heavily segmented. They have three pairs of legs that extend from the thorax. The length of the head of each louse is approximately 1 millimeter and the length of the whole louse is about 6 to 7 millimeters.

Another human parasite common throughout history is the flea; as poet Ogden Nash wrote, “Adam had ’em.” Fleas (order Siphonaptera) are wingless insect parasites in which the adults jump instead of crawl, so they spend less time than lice directly on their host, although they can jump on and off. After sucking blood, fleas produce larvae that spin a cocoon and can remain dormant for many months, until they sense the presence of a host. Fleas often alternate among different animal hosts, such as cats or dogs, although a given flea species usually has a preference for a particular animal species. Fleas carry various kinds of pathogens, most famously the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis (see Section 10.3).

Other insects, such as mosquitoes, alight briefly on their host to suck blood and then depart to produce eggs. Mosquito eggs require stagnant water to develop into larvae that pupate. Mosquitoes themselves are technically not parasites, but they carry and transmit many kinds of pathogens, such as the malaria parasite and the yellow fever virus.

A different kind of reproductive strategy is that of the botfly (such as Dermatobia hominis, which seeks a human host). The adult botfly does not feed at all, but it attaches its eggs to a smaller fly, seemingly innocuous, which then deposits the botfly eggs on a host animal or human. Each egg burrows under the skin, where it develops as a larva. The parasitic larvae do not kill the host, but their presence can be painful. The larva ultimately crawls out from the host and falls off to the ground in order to pupate.

health equity

Hookworms from Open Sewage

It may come as a surprise to learn that more than a million American citizens lack a proper sewage system for their homes—and in some cases are fined for their inability to pay for it. Lack of sewage treatment leads to developmental problems and diarrhea, as well as to infections by parasites such as hookworms. But some state and local governments overlook the problem. In one Alabama county where the cost of a septic system nearly exceeds the median income, the local health department reported “no hookworm” in the community—yet 30% of residents tested positive for hookworm.

In rural counties of Alabama, hookworm infections disproportionately affect low-income Black families. Instead of fixing the sewage systems in these counties, the state prosecuted residents for wastewater violations. In effect, citizens were punished for lacking access to basic sanitation, something taken for granted by most American communities.

To address the problem, an organization now called the Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice filed a lawsuit against the state. The lawsuit was finally settled in 2023—the first settlement of an environmental justice case under federal civil rights laws. In the settlement, the US Department of Justice and Department of Health and Human Services required the state of Alabama to suspend arrest warrants and criminal penalties for residents lacking sanitation. Instead, the state must assess and address the wastewater management systems of counties with septic problems. In addition, a public health awareness campaign was required to educate citizens on their rights and options to achieve effective sanitation that can prevent hookworm and other diseases.

A growing problem worldwide is the bedbug (Figure 11.29). Human bedbugs (Cimex lectularius) find their hosts at night while their human targets are asleep; the bugs detect the host mainly from the exhaled carbon dioxide. Unnoticed, the bedbugs suck the host’s blood and depart to lay eggs. Their bites lead to allergic reactions and psychological trauma. Bedbugs were nearly eradicated from the United States in the mid-twentieth century by the use of DDT and other pesticides. Today, bedbugs resist the older pesticides and can be killed only by newer chemicals that are restricted because of their side effects. Elimination is possible but costly, and the persistent bugs spread especially fast through the homes of senior citizens who cannot afford home treatment. Hotels, movie theaters, and homes of all economic levels are now affected. Some bedbugs reportedly carry dangerous pathogens, such as MRSA, although their ability to transmit disease remains unproven.

A photo of a person holding a jar containing bed bugs. The bugs are collected in a large pile at the bottom of the glass jar.

A photo of a bed bug on skin. The bug has a broad, flattened head that narrows to a pointed clypeus. The clypeus pierces into the skin. Behind its head, the bed bug has a broad thorax and an elongated ovoid abdomen. It has three pairs of bent legs that extend from the thorax. The abdomen is segmented throughout its length. The length of the bedbug is approximately 3.5 millimeters.

SECTION SUMMARY

Thought Question 11.5 The X-Files episode “The Host” depicts a human-sized worm as a “liver fluke” that is claimed to have a “scolex” and to regenerate from a cut piece. Which two different kinds of worms are confused in this description?

The X-Files episode referred to the worm as a “fluke” that attached to the bile duct of a liver, but the parasite’s head was depicted as a “scolex.” The scolex is a specialized form with hooks and suckers found on a tapeworm, not a fluke. In addition, the ability of a cutoff piece (a segment) to reproduce is characteristic of a tapeworm, not a fluke.

Thought Question 11.6 Overall, why do eukaryotic parasites show such a wide range of size? What selective forces favor large size, and what forces favor small size?

The advantage of large size, for a parasite, is that larger organisms can consume more food to produce large numbers of progeny. On the other hand, the larger parasite is more likely to shorten the life span of the host. The smaller the parasite, the greater the number of individuals that can be made with finite resources. So, many kinds of parasites alternate between large and small developmental stages. An extreme example is tapeworms, which may grow to many meters in length, with a large number of independently reproductive segments. The ova and larvae, however, are microscopic, so large numbers can be made.