SECTION OBJECTIVES

- Distinguish between the signs and symptoms of a disease.

- Explain the role of immunopathogenesis in infectious disease.

- Describe the five basic stages of an infectious disease.

SECTION OBJECTIVES

How do we define disease? A disease is a disruption of the normal structure or function of any body part, organ, or system that can be recognized by a characteristic set of symptoms and signs (described shortly). An infectious disease, then, is a disease caused by a microorganism (bacterial, viral, or parasitic) that can be transferred from one host to another. Table 2.1 presents the terms commonly used to describe the features of infectious disease. It is critically important for you to learn these terms because they will be used repeatedly throughout this book and, very likely, in your future career.

|

Table 2.1 Terms Used to Describe Infections and Infectious Diseases |

||

|

Term |

Definition |

Example(s) |

|

Acute infection |

Infection in which symptoms develop rapidly; its course can be quick or protracted. |

Strep throat (Streptococcus pyogenes) |

|

Chronic infection |

Infection in which symptoms develop gradually, over weeks or months, and are slow to resolve (heal), taking 3 months or more. |

Tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) |

|

Subacute disease |

Infection in which symptoms take longer to develop than in an acute infection but arise more quickly than in a chronic infection. |

Subacute bacterial endocarditis (Enterococcus faecalis) |

|

Latent infection |

Infection that may occur after an acute episode; the organism is present, but symptoms are not. After time, the disease can reappear. |

Cold sores due to herpesvirus |

|

Focal infection |

Initial site of infection, from which organisms can travel via the bloodstream to another area of the body. |

Boils (Staphylococcus aureus) |

|

Disseminated infection |

Infection caused by organisms traveling from a focal infection to other parts of the body; when affecting several organ systems, it is called a systemic infection. |

Tularemia (Francisella tularensis) |

|

Metastatic infection |

Site of infection resulting from dissemination. |

Blastomycosis, fungal infection of the lung; can disseminate to form abscesses in the extremities (arms/legs) |

|

Bacteremia |

Presence of bacteria in blood; usually transient, little, or no replication. |

May occur during dental procedures (Streptococcus mutans) |

|

Septicemia |

Presence and replication of bacteria in the blood (blood infection). |

Plague (Yersinia pestis) |

|

Viremia |

Presence of viruses in the blood. |

HIV |

|

Toxemia |

Presence of toxin in the blood. |

Diphtheria, toxic shock syndrome |

|

Primary infection |

Infection in a previously healthy individual. |

Syphilis (Treponema pallidum) |

|

Secondary infection |

Infection that follows a primary infection; damaged tissue (e.g., lung) is more susceptible to infection by a different organism. |

Bacterial infection following viral influenza (Haemophilus influenzae) |

|

Mixed infection |

Infection caused by two or more pathogens. |

Appendicitis (Bacteroides fragilis and Escherichia coli) |

|

Iatrogenic infection |

Infection transmitted from a health care worker to a patient. |

Some septicemias (Staphylococcus aureus) |

|

Health care–associated infection (HAI) |

Infection acquired while receiving medical care; often preventable. An HAI acquired during a hospital stay is called a nosocomial infection. |

MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) |

|

Community-acquired infection |

Infection acquired in the community, not in a hospital. |

Some MRSA strains, influenza, HIV |

Most diseases are recognized by their signs and symptoms. A sign is something that can be observed by a person examining the patient; a runny nose, a rash, sweating, fever, and high blood pressure are examples of signs. Brandon’s lesion in the chapter-opening case history was an obvious disease sign. A symptom is something that can be felt only by the patient, such as pain or general discomfort (malaise). Some signs can also be called symptoms if the patient alone witnessed them. For example, a rash that went away before a clinician saw it would be a symptom that is reported to the clinician. A syndrome is a collection of signs and symptoms that occur together and signify a particular disease.

It is important to realize that many of the signs and symptoms of an infectious disease are actually caused by the host’s response to the infection (called immunopathology). Cells given the task of killing the microbe can also damage nearby host tissue, causing signs and symptoms such as runny nose, rash, and headaches. Even after an infectious disease has resolved, pathological consequences called sequelae (singular, sequela) may develop. For instance, the immune response to strep throat (caused by Streptococcus pyogenes) can produce heart damage (rheumatic fever) or kidney disease (acute glomerulonephritis) weeks after the infection has resolved.

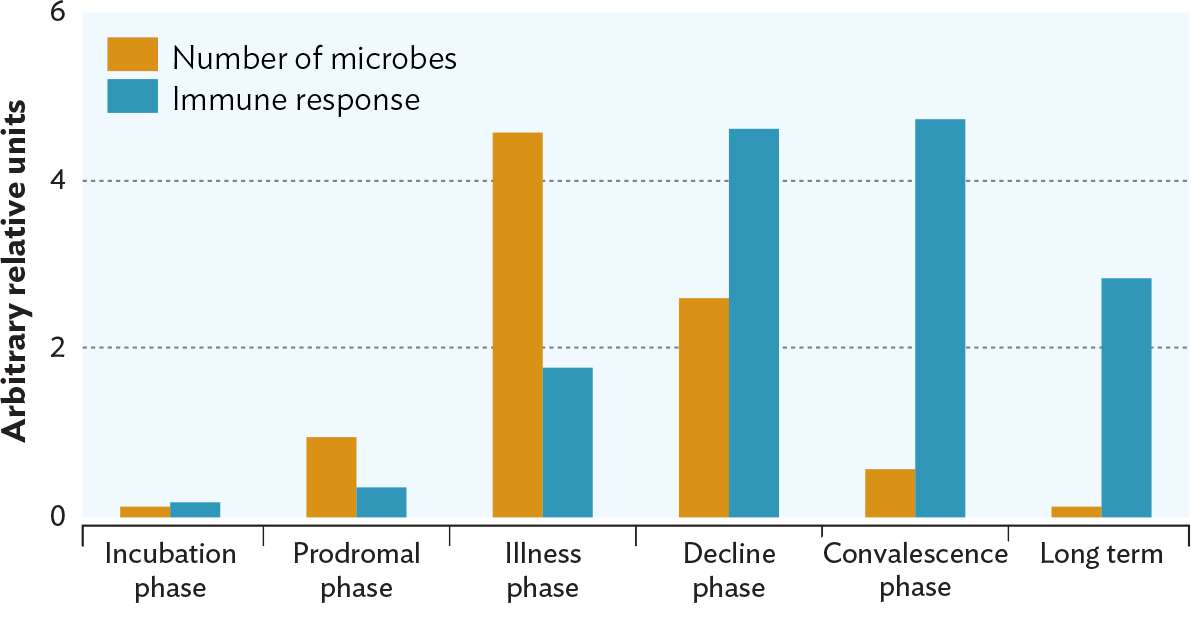

The stages (or phases) of a disease reflect how the contest between an infectious agent and a host progresses (Figure 2.8). At first, the microbe has the “upper hand” and the patient displays only minor, if any, signs or symptoms. After the immune system recognizes the threat, it begins to attack the invader, which can initially cause symptoms to worsen. As the immune system kills the pathogen, the symptoms decline in severity, and the host recovers. Most infections go through these stages, even when treated with antibiotics (although symptoms are much less severe).

A photo of a woman checking the temperature of a child. The woman is laying in bed next to the child and reading the temperature on a stick thermometer held out before her. The child appears to be feeling sick.

A bar chart of the relative number of microbes and intensity of the immune response at different phases of an infection. The X axis displays the six phases of infection. The phases are incubation phase, prodromal phase, illness phase, decline phase, convalescence phase, and long term. The Y axis displays arbitrary relative units from 0 to 6. Each infection phase has two vertical bars, orange representing number of microbes, and blue representing the immune response. The number of microbes and the immune response for the incubation phase is relatively low, around 0.1 for the number of microbes and 0.12 for the immune response. In the prodromal phase, the number of microbes is 1, and the immune response is 0.4. In the illness phase, The number of microbes is 4.5, and the immune response is 1.8. In the decline phase, the number of microbes is 2.75, and the immune response is 4.5. In the convalescence phase, the number of microbes is 0.75, and the immune response is 4.7. In the long term phase, the number of microbes is 0.1, and the immune response is 3.

The incubation phase is the time after a microbe first infects a person until the first signs of disease appear. Depending on the disease, patients may be contagious—that is, able to transmit the organism to someone else—even though they themselves appear healthy. For instance, a child with chickenpox can start to shed virus 5 days before the rash appears. A patient with COVID-19 can shed the SARS-CoV-2 virus for 2 days before symptoms appear. During an incubation period, the pathogen is trying to replicate to larger and larger numbers before the immune system knows it’s under attack. Actually, most infections never progress to active disease, because the invading microbe succumbs to early host defenses. This explains why people who have never had symptoms of Lyme disease or COVID-19, for example, can have antibodies against Borrelia burgdorferi or SARS-CoV-2, respectively, in their blood. How long the incubation period lasts before signs of disease appear depends on many factors, including the infectious dose, the host’s health status, and the tools of pathogenicity available to the microbe.

The prodromal phase (or prodrome), which develops after the incubation phase, is short and may not even be apparent. It involves vague symptoms, such as headache or a general feeling of malaise (fatigue and mild body discomfort), that warn of more serious signs and symptoms to come. For example, a child infected with measles virus will experience a prodromal phase marked by fever and a runny nose before the characteristic red, spotty rash develops. As with the incubation period, people in the prodromal phase can spread the microbe to others.

The illness phase begins when typical symptoms and signs of the disease appear. The pathogen reaches peak numbers during this phase. Symptoms start to develop once the immune system begins attacking the organism or virus. The point at which disease symptoms are most severe is called the acme. The battle between microbe and host is at its peak during this time. Fever is a sign or symptom often seen during the illness phase.

Fever, though uncomfortable, is actually a protective mechanism to fight infection. High body temperatures can help our immune system function better and can inhibit microbial growth. Children can generally tolerate a fever of 41°C (106°F), but for adults, 39.4°C (103°F) is about the safe limit. Above that temperature, brain damage can occur. How fever is triggered and why it is important is discussed further in Section 15.6, where inflammation and the immune response are covered.

The decline phase of a disease begins as the immune system becomes proficient at killing the pathogen, the invader’s numbers begin to decrease, and the patient’s symptoms subside. Host defenses have won. As the infection recedes, fewer pyrogens (the compounds that trigger fever) are made, and the body’s thermostat is reset to the lower temperature. To restore body temperature, blood vessels will dilate to lose heat (vasodilation), and the patient will start to sweat. These are the signs that a fever is “breaking.”

Convalescence is the period after the decline phase, once symptoms have completely disappeared. The patient begins to recover strength and normal health. The immune system remains at the ready as the patient recovers, but its ability to attack the same invader will wane over the years.

When discussing infectious diseases, we often use the terms “morbidity” and “mortality.” Morbidity refers to the existence of a disease state and the rate of incidence of the disease. Incidence refers to new cases of the disease that develop during a given period of time, usually a year (see Chapter 26). You do not have to die to be included in a morbidity statistic; you only need to be sick. Mortality, on the other hand, is a measure of how many patients have died from a disease. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) publishes a report called the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) that discusses current outbreaks, statistics, and other health topics. Table 2.1 lists several other terms often used by medical professionals that you should master before proceeding.

SECTION SUMMARY

— Incubation period, when the organism begins to grow but symptoms have not developed

— Prodromal phase, which can be unapparent or show vague symptoms

— Illness phase, when signs and symptoms are apparent and the immune system is fighting the disease

— Decline phase, when the numbers of pathogens decrease and symptoms abate

— Convalescence, when symptoms are gone and the patient recovers

Thought Question 2.3 Why would quickly killing a host be a bad strategy for a pathogen?

The goal of any microbe is to maintain its species. If a microbe does not have an opportunity to easily spread to a new host, killing its host is tantamount to suicide.

Thought Question 2.4 Chapter 1 explained Koch’s postulates and how they are used to determine the etiology of a disease (see Figure 1.13). The postulates say that you must find the same organism in each case of a disease in order to say that the organism causes the disease. Suppose three individuals with septicemia (a blood infection) have been admitted to the hospital. The clinical laboratory identifies E. coli in the blood of one, Enterococcus in the blood of another, and Yersinia pestis in the blood of the third. Do these findings defy Koch’s postulates? After all, the same organism was not identified in each case.

The key in this case is that you know blood should not harbor any microorganisms. So the question is not whether you always find E. coli in someone with septicemia, but rather, do you ever find a case of septicemia when there is no bacteria in the patient’s blood? The answer is no. Yet the blood of anyone with clear signs of septicemia will contain some species of bacteria. The species of pathogen can be different for different cases.