VIDEO

Lighting and Character in Atonement

The remaining chapters in this book describe the major formal aspects of film—narrative, mise-en-scène, cinematography, acting, editing, sound—to provide you with a beginning vocabulary for talking about film form more specifically. Before we study these individual formal elements, however, let’s briefly discuss three fundamental principles of film form:

Light is the essential ingredient in the creation and consumption of motion pictures. Movie images are made when a camera lens focuses light onto either film stock or a digital video sensor. Movie-theater projectors and video monitors all transmit motion pictures as light, which is gathered by the lenses and sensors in our own eyes. Movie production crews—including the cinematographer, the gaffer, the best boy, and many assorted grips and assistants—devote an impressive amount of time and equipment to illumination design and execution. Yet it would be a mistake to think of light as simply a requirement for a decent exposure. Light is more than a source of illumination; it is a key formal element that film artists and technicians carefully manipulate to create mood, reveal character, and convey meaning.

One of the most powerful black-and-white films ever made, John Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath (1940), tells the story of an Oklahoma farming family forced off their land by the violent dust storms that plagued the region during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The eldest son, Tom Joad, returns home after serving a prison sentence only to find that his family has left their farm for the supposedly greener pastures of California.

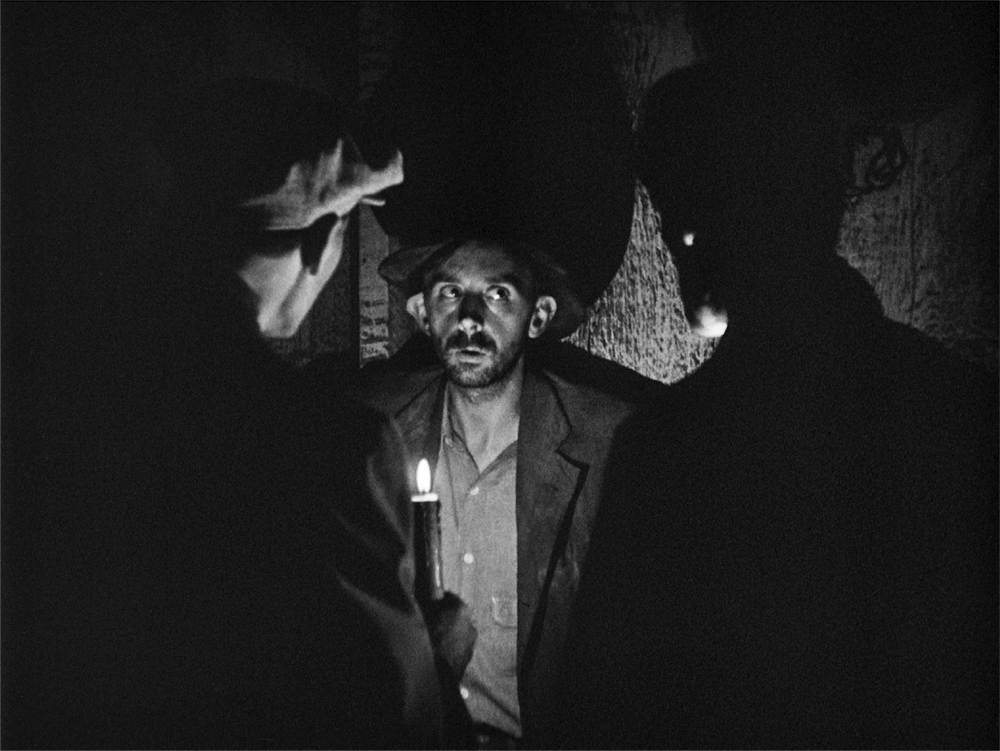

Tom and an itinerant preacher named Jim Casy, whom he has met along the way, enter the Joad house, using a candle to help them see inside the pitch-black interior. Lurking in the dark, but illuminated by the candlelight (masterfully simulated by cinematographer Gregg Toland), is Muley Graves, a farmer who has refused to leave Oklahoma with his family. As Muley tells Tom and Casy what has happened in the area, Tom holds the candle so that he and Casy can see him better [1], and the contrasts between the dark background and Muley’s haunted face, illuminated by the flickering candle, reveal their collective state of mind: despair. The unconventional direction of the harsh light distorts the characters’ features and casts elongated shadows looming behind and above them [2]. The story is told less through words than through the overtly symbolic light of a single candle.

Expressive use of light in The Grapes of Wrath

Strong contrasts between light and dark (called chiaroscuro) make movies visually interesting and focus our attention on significant details. But that’s not all that they accomplish. They can also evoke moods and meanings, and even symbolically complement the other formal elements of a movie, as in these frames from John Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath (1940).

Muley’s flashback account of the loss of his farm reverses the pattern. The harsh light of the sun that, along with the relentless wind, has withered his fields beats down upon Muley, casting a deep, foreshortened shadow of the ruined man across his ruined land [3]. Such sharp contrasts of light and dark occur throughout the film, thus providing a pattern of meaning.

It is useful to distinguish between the luminous energy we call light and the crafted interplay between motion-picture light and shadow known as lighting. Light is responsible for the image we see on the screen, whether photographed (shot) on film or video or created with a computer. Lighting is responsible for significant effects in each shot or scene. It enhances the texture, depth, emotions, and mood of a shot. It accents the rough texture of a cobblestoned street in Carol Reed’s The Third Man (1949), helps to extend the illusion of depth in Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941), and emphasizes a character’s subjective feelings of apprehension or suspense in such film noirs as Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944). In fact, lighting often conveys these things by augmenting, complicating, or even contradicting other cinematic elements within the shot (e.g., dialogue, movement, or composition). Lighting also affects the ways that we see and think about a movie’s characters. It can make a character’s face appear attractive or unattractive, make the viewer like a character or be afraid of her, and reveal a character’s state of mind.

These are just a few of the basic ways that movies depend on light to achieve their effects. We’ll continue our discussion of cinema’s use of light and manipulation of lighting later (Chapter 5 examines lighting as an element of mise-en-scène; Chapter 6 includes information and analysis of lighting’s role in cinematography; Chapter 11 covers how motion-picture technologies capture and use light). For now, it’s enough to appreciate that light is essential to movie meaning and to the filmmaking process itself.

We need light to make, shape, and see movies, but it takes more than light to make motion pictures. As we learned in Chapter 1, movement is what separates cinema from all other two-dimensional pictorial art forms. We call them movies for a reason: cinema’s expressive power largely derives from the medium’s fundamental ability to move. Or, rather, it seems to move. As we sit in a movie theater, believing ourselves to be watching a continually lit screen portraying fluid, uninterrupted movement, we are actually watching a quick succession of still photographs called frames. There is still some debate among cognitive scientists as to exactly why the brain processes a rapid series of still images as continuous movement. Essentially, when viewing successive images depicting only slight differences from frame to frame at a high enough speed, the brain’s visual systems respond using the same motion detectors used to perceive and translate real motion in our everyday lives. For our purposes, what’s important is (a) it works, as the marvelously expressive medium we’re studying could not exist without this convenient brain glitch, and (b) we recognize the still photographic frame as the basic building block of motion pictures.

VIDEO

Lighting and Character in Atonement

Lighting and character in Atonement

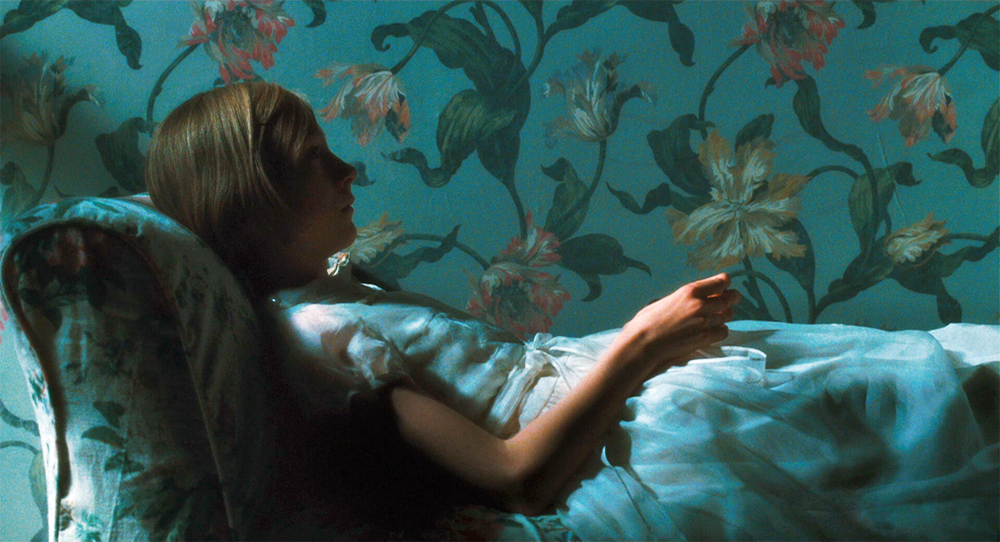

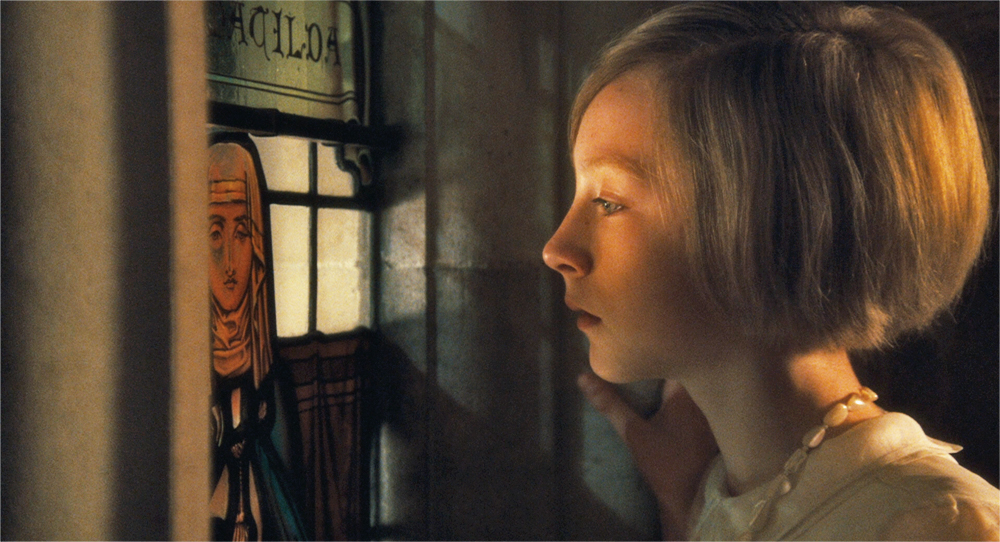

Filmmakers often craft the interplay between illumination and shadow to imply character state of mind. The tragic romance of Atonement (2007; director Joe Wright) hinges on the actions of a precocious thirteen-year-old, Briony Tallis. Lives are irrevocably altered when Briony’s adolescent jealousy prompts her to accuse the housekeeper’s son Robbie of rape. As events unfold, a series of different lighting designs are employed to enhance our perception of Briony’s evolving (and often suppressed) emotions as she stumbles upon Cecilia and Robbie making love in the library [1], catches a startled glimpse of her cousin’s rape [2], accuses Robbie of the crime [3], guiltily retreats upon Robbie’s arrival [4], contemplates the consequences of her actions [5], and observes Robbie’s arrest [6].

In the early days of cinema, when these continuous successions of frames were shot and shown using long strips of celluloid film, filmmakers and exhibitors discovered that the shooting and projection of at least 24 images per second was needed to present smooth, natural-looking movement. Projectors were developed that could perform a complex mechanical task 24 times every second: shine light through a frame to project its image, and then move the next frame into place for its moment of projection. A shutter was used to block the light and thus obscure the mechanical movement of each new frame being moved into place, so that the screen was actually momentarily dark at least 24 times every second. Aspects of eye and brain function that blend rapid flashes of light and momentarily retain an image after the eye records it make those moments of darkness undetectable. New rotating multi-blade shutters were soon developed that momentarily interrupted the projection of each frame with a microsecond of black screen, so that audiences were actually seeing two projections of each frame before the projector mechanism replaced it with the next frame. By further increasing the number of projected images flashing across the screen each second, these shutters helped to further smooth the appearance of motion and eliminate any visible flicker on-screen. These days, when most movies are shot on high-definition video using digital cameras, and virtually every movie is viewed digitally—whether in a movie theater using a digital projector or on a digital TV or other device—the brief moments of black are no longer necessary. Most movies are still shot and projected at 24 frames per second, although some recent films (such as Peter Jackson’s Hobbit trilogy) have experimented with higher frame rates.

Some of the arts, such as architecture, are concerned mostly with space; others, such as music, are related mainly to time. But movies manipulate space and time equally well, so they are both a spatial and a temporal art form. Movies can move seamlessly from one space to another (say, from a room to a landscape to outer space), or make space move (as when the camera turns around or away from its subject, changing the physical, psychological, or emotional relationship between the viewer and the subject), or fragment time in many different ways. Only movies can record real time in its chronological passing as well as subjective versions of time passing—slow motion, for example, or extreme compression of vast swaths of time.

On the movie screen, space and time are relative to each other, and we can’t separate them or perceive one without the other. The movies give time to space and space to time, a phenomenon that art historian and film theorist Erwin Panofsky describes as the dynamization of space and the spatialization of time.1 To understand this principle of “co-expressibility,” compare your experiences of space when you watch a play and when you watch a movie. As a spectator at a play in the theater, your relationship to the stage, the settings, and the actors is fixed. Your perspective on these things is determined by the location of your seat, and everything on the stage remains the same size in relation to the entire stage. Sets may change between scenes, but within scenes the set remains, for the most part, in place. No matter how skillfully constructed and painted the set is, you know (because of the clear boundaries between the set and the rest of the theater) that it is not real and that when actors go through doors in the set’s walls, they go backstage or into the wings at the side of the stage, not into a continuation of the world portrayed on the stage.

By contrast, when you watch a movie, your relationship to the space portrayed on-screen can be flexible. You still sit in a fixed seat, but the screen images move: the spatial relationships on the screen may constantly change, and the film directs your gaze. Suppose, for example, that during a scene in which two characters meet at a bar, the action suddenly flashes forward to their later rendezvous at an apartment, then flashes back to the conversation at the bar, and so on; or a close-up focuses your attention on one character’s (or both characters’) lips. A live theater performance can attempt versions of such spatial and temporal effects, but a play can’t do so as seamlessly, immediately, persuasively, or intensely as a movie can. If one of the two actors in that bar scene were to back away from the other and thus disappear from the screen, you would perceive her as moving to another part of the bar, that is, into a continuation of the space already established in the scene. You can easily imagine this movement due to the fluidity of movie space, more of which is necessarily suggested than is shown.

The motion-picture camera doesn’t simply record the space in front of it: it deliberately determines and controls our perception of cinematic space. In the hands of expressive filmmakers, the camera selects what space we see and uses framing, lenses, and movement to determine exactly how we see that space. This process, by which an agent transfers something from one place to another (in this case, the camera transferring aspects of space to the viewer) is known as mediation. When we watch a movie, especially under ideal conditions with a large screen in a darkened room, we identify with the lens. In other words, viewers exchange the viewpoint of their own eyes for the mediated viewpoint of the camera. The camera captures space differently than do the eyes, which have peripheral vision and can only move through space (and time) along with the rest of the body. The camera’s viewpoint is limited only by the edges of the frame. It fragments space into multiple edited images that can jump instantaneously between different angles and positions, looking through variable lenses that present depth and perspective in a number of ways. And yet, because of our natural tendency to use visual information to understand the space around us, the brain is able to automatically accept and process the camera’s different way of seeing and use that mediated information to comprehend cinematic space.

VIDEO

Manipulating Space in The Gold Rush

Manipulating space in The Gold Rush

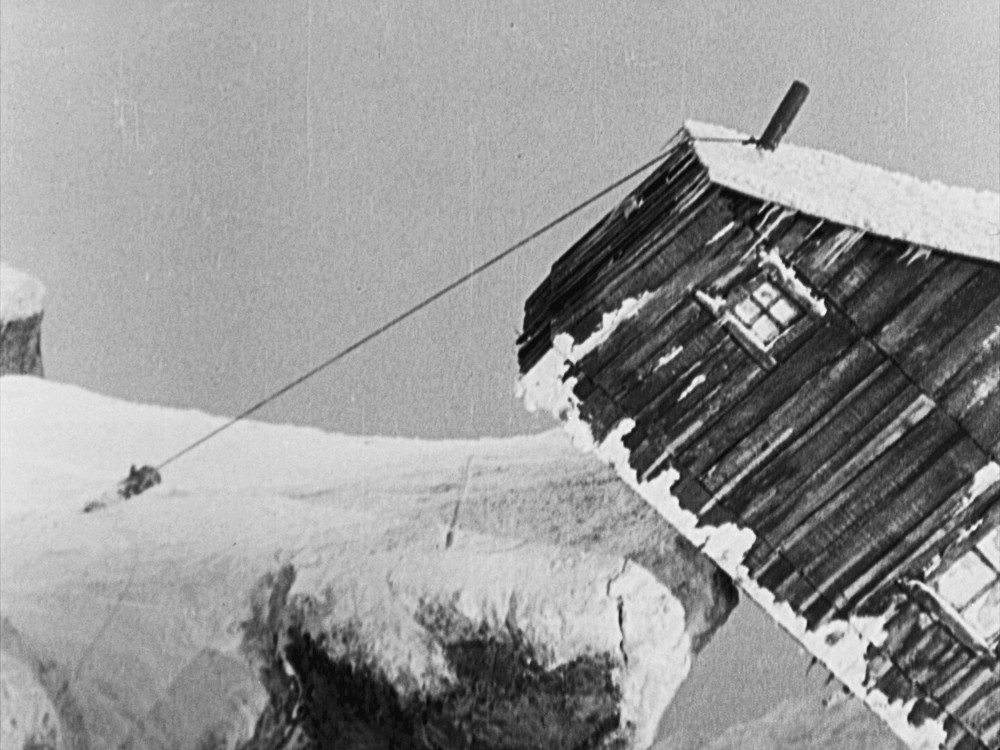

Film editing can convince us that we’re seeing a complete space and a continuous action, even though individual shots have been filmed in different places and at different times. In Charles Chaplin’s The Gold Rush (1925), an exterior shot of the cabin [1] establishes the danger that the main characters only slowly become aware of [2]. As the cabin hangs in the balance [3], alternating interior and exterior shots [4–6] accentuate our sense of suspense and amusement.

Cinema’s ability to mediate space is illustrated in Charles Chaplin’s The Gold Rush (1925). This brilliant comedy portrays the adventures of two prospectors: the “Little Fellow” (Chaplin) and his partner, Big Jim McKay (Mack Swain). After many twists and turns of the plot, the two find themselves sharing an isolated cabin. At night, the winds of a fierce storm blow the cabin to the edge of a cliff, leaving it precariously balanced on the brink of an abyss. Waking and walking about, the Little Fellow slides toward the door (and almost certain death). The danger is established by our first seeing the sharp precipice on which the cabin is located and then by seeing the Little Fellow sliding toward the door that opens out over the chasm. Subsequently, we see him and Big Jim engaged in a struggle for survival that requires them to maintain the balance of the cabin on the edge of the cliff.

The suspense exists because individual shots—one made outdoors, the other safely in a studio—have been edited together to create the illusion that they form part of a complete space. As we watch the cabin sway and teeter on the cliff’s edge, we imagine the hapless adventurers inside; when the action cuts to the interior of the cabin and we see the floor pitching back and forth, we imagine the cabin perched precariously on the edge. The experience of these shots as a continuous record of action occurring in a complete (and realistic) space is an illusion that no other art form can convey as effectively as movies can.

The manipulation of time (as well as space), a function of editing, is handled with great irony, cinematic power, and emotional impact in the “baptism and murder” scene in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972). This 5-minute scene consists of thirty-six shots made at different locations. The primary location is a church where Michael Corleone, the newly named godfather of the Corleone mob, and his wife, Kay, attend their nephew’s baptism. Symbolically, Michael is also the child’s godfather. Coppola cuts back and forth between the baptism; the preparations for five murders, which Michael has ordered, at five different locations; and the murders themselves.

Each time we return to the baptism, it continues where it left off for one of these cutaways to other actions. We know this from the continuity of the priest’s actions, Latin incantations, and the Bach organ music. This continuity tells us not only that these actions are taking place simultaneously but also that Michael is involved in all of them, either directly or indirectly. The simultaneity is further strengthened by the organ music, which underscores every scene in the sequence, not just those that take place in the cathedral. As the priest says to Michael, “Go in peace, and may the Lord be with you,” we are left to reconcile this meticulously timed, simultaneous occurrence of sacred and criminal acts.

Movies manipulate time

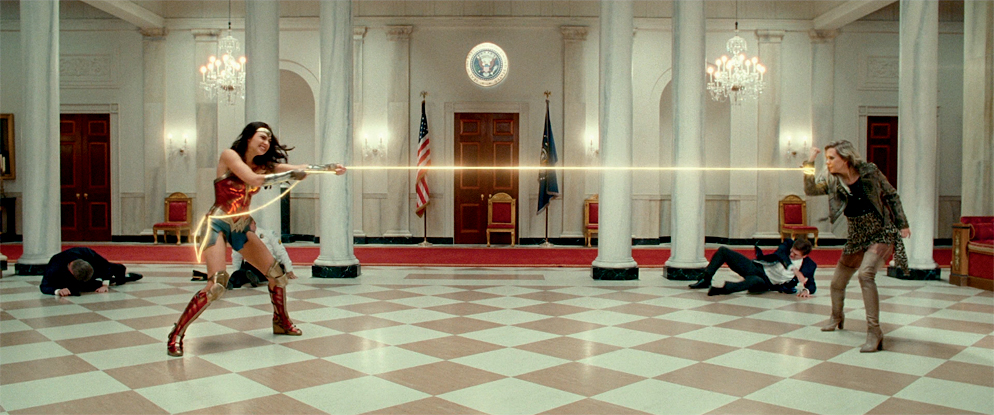

A number of recently released films offer ample evidence that rearranging chronology isn’t the only way movies manipulate time. During fight scenes in Wonder Woman 1984 (2020; director Patty Jenkins), the title character’s powers are visualized using speed ramping, a technique in which action speeds up and slows down within a single shot [1]. In Cathy Yan’s Birds of Prey (2020), the frenetic way that time speeds up, jumps forward, rewinds, and freezes in place reflects the manic energy of the narrator (and main character), Harley Quinn [2]. The past and the present intersect for a detective in Don’t Let Go (2019; director Jacob Estes) when his recently murdered niece starts calling him from an alternate timeline [3]. The Netflix series Russian Doll (2019; creators Natasha Lyonne, Amy Poehler, and Leslye Headland) and the romantic comedy Palm Springs (2020; director Max Barbakow) [4] share a similar time-sensitive premise. Each takes place all in one day, but that day is repeated multiple times as the protagonists struggle to break free of the time loop they’re stuck inside. The protagonist of Charlie Kaufman’s surreal I’m Thinking of Ending Things (2020) has the opposite problem. Her awkward trip to meet her boyfriend’s parents ricochets unpredictably between different time frames, perspectives, and realities [5]. Some characters in Christopher Nolan’s Tenet (2020) have the ability to reverse entropy, causing a “time inversion” that gives us scenes in which time seems to move forward for some characters while simultaneously running in reverse for others [6].

The parallel action sequences in The Silence of the Lambs, Way Down East, and The Godfather are evidence of cinema’s ability to use editing to represent multiple events occurring at the same instant. Some movies, like BlacKkKlansman (2018; director Spike Lee), do parallel action one better, using a split screen to show the concurrent actions simultaneously.

Split screen manipulates time and space

Most movies use crosscutting techniques like parallel action to represent more than one event occurring at the same moment. City of God (2002; directors Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund) sometimes breaks with convention and splits the screen into multiple frames to present a more immediate depiction of simultaneous action [1]. This split screen from Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018; directors Bob Persichetti, Peter Ramsey, and Rodney Rothman) manipulates time and space in a different way. Multiple actions are presented simultaneously, but all of the events depicted occurred not just in different places but at different times as well [2].

Movies frequently rearrange time by organizing story events in nonchronological order. Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941) and Todd Haynes’s I’m Not There (2007) both begin their exploration of a life with that character’s death and, for the rest of the film, shuffle the events leading up to that opening conclusion. Movies such as Love and Mercy (2014; director Bill Pohlad) inform our perspective on characters and events by alternating between past and present time frames. The science-fiction film Arrival (2016; director Denis Villeneuve) reorders time in ways that challenge viewer expectations of chronology (and consciousness) when scenes initially assumed to take place in the past are revealed to be glimpses of future events. A number of films, most famously Christopher Nolan’s Memento (2000) and Gaspar Noé’s Irréversible (2002), transpose time by presenting their stories in scene-by-scene reverse chronological order. All of these approaches to rearranging time allow filmmakers to create new narrative meaning by juxtaposing events in ways linear chronology does not permit.

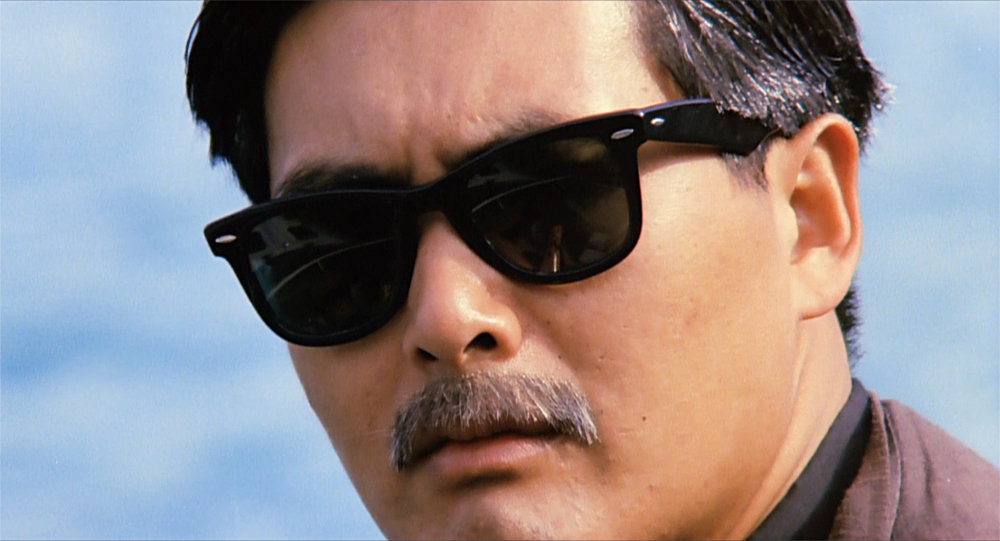

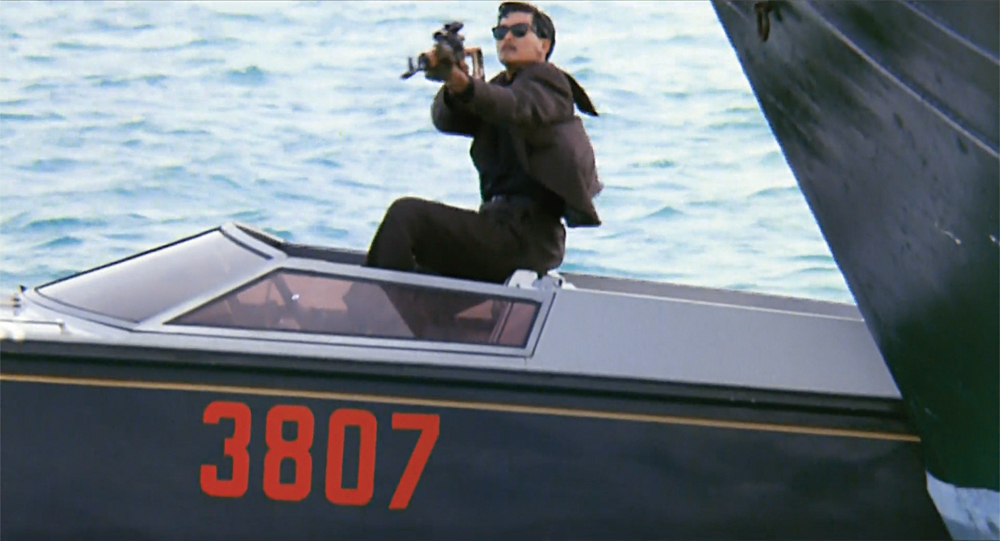

John Woo’s 1989 action extravaganza The Killer maintains conventional chronology but uses many other expressive manipulations of time to tell its story of a kindhearted assassin and the relentless cop determined to capture him. Each of the film’s many gun-battle scenes features elegant slow-motion shots of either the antihero or one of his unfortunate rivals delivering or absorbing multiple bullets. The slow motion invites the audience to pause and savor an extended moment of stylized violence. The sequences also employ occasional bursts of fast motion that have the opposite effect. These sudden temporal shifts allow Woo and film editor Fan Kung Ming to choreograph cinematic patterns and rhythms that give their fight scenes a dizzying kinetic energy that borders on the outrageous.

Woo expands the audience’s experience of time at key points in the story by fragmenting the moment preceding an important action. The film’s climactic gunfight finds the hit man and the cop allied against overwhelming forces. The sequence begins with several shots of an army of trigger-happy gangsters bursting into the isolated church where the unlikely partners are holed up. The film extends the brief instant before the bullets fly with a series of twelve shots, including a panicked bystander covering her ears, a priest crossing himself, and the cop and killer exchanging tenacious glances. The accumulation of these time fragments holds us in the moment far longer than the momentum of the action could realistically allow. The sequence’s relative stasis establishes a pattern that is broken by the inevitable explosion of violence. Later, a brief break in the combat is punctuated by a freeze-frame (in which a still image is shown on-screen for a period of time), another of Woo’s time-shifting trademarks. Bloodied but still breathing, the newfound friends emerge from the bullet-ridden sanctuary. The killer’s fond glance at the cop suddenly freezes into a still image, suspending time and motion for a couple of seconds. The cop’s smiling response is prolonged in a matching sustained freeze-frame. As you may have guessed, The Killer is an odd sort of love story. With that in mind, we can see that these freeze-frames do more than manipulate time; they visually unite the two former foes, thus emphasizing their mutual admiration.

One of the most dazzling manipulations of both space and time the movies have to offer was perfected and popularized by Lana and Lilly Wachowski (as the Wachowski brothers) with their 1999 science-fiction film, The Matrix. This effect, known—for reasons that will become obvious—as bullet time, is critical to one of the film’s pivotal scenes. In the scene, the hacker-turned-savior-of-humanity Neo transcends real-world physics and bends the Matrix to his purposes for the first time. When one of the deadly digital henchmen known as agents shoots at Neo, the action suddenly reverts to stylized slow motion as Neo literally bends over backward to avoid the projectiles. The slow motion allows us to see “speeding” slugs and lends a balletic grace to Neo’s movements. But what makes the moment magical—and conveys our hero’s newfound mastery—is the addition of an extra and unexpected time reference: a swooping camera that circumnavigates the slo-mo action at normal real-time speed. To achieve this disorienting and spellbinding combination of multiple speeds, the filmmakers worked with engineers to develop new technology in a process that resembled sequence photography experiments from the earliest days of motion-picture photography (see illustrations on p. 41). Neo’s dodging dance was shot not by one motion-picture camera, but by 120 still cameras mounted in a roller-coaster-style arc and snapping single images in a computer-driven, rapid-fire sequence. When all those individual shots are projected in quick succession, the subject appears to move slowly while the viewpoint of the camera capturing that subject maintains its own independent fluidity and speed.

Manipulating time in The Killer

The world-weary title character in John Woo’s The Killer (1989) is an expert assassin attempting to cash in and retire after one last hit. Woo conveys the hit man’s reluctance to kill again by expanding the moment of his decision to pull the trigger. Film editor Fan Kung Ming fragments the dramatic pause preceding the action into a thirty-four-shot sequence that cuts between multiple images of the intended target [1], the dragon-boat ceremony he is officiating [2, 3], and the pensive killer [4, 5]. The accumulation of all these fragments extends what should be a brief moment into a tension-filled 52 seconds. When the killer finally does draw his weapon, the significance of the decision is made clear by the repetition of this action in three shots from different camera angles [6–8]. The rapid-fire repetition of a single action is one of cinema’s most explicit manipulations of time.

Movement in The Matrix

For Lana and Lilly Wachowski’s The Matrix (1999), special effects supervisors Steve Courtley and Brian Cox employed a setup much like that used by early pioneers of serial photography (see Chapter 10). They placed 120 still cameras in an arc and coordinated their exposures using computers. The individual frames, shot from various angles but in much quicker succession than is possible with a motion-picture camera, could then be edited together to create the duality of movement (sometimes called bullet time) for which The Matrix is famous. The camera moves around a slow-motion subject at a relatively fast pace, apparently independent of the subject’s stylized slowness. Despite its contemporary look, this special effects technique is grounded in principles and methods established during the earliest years of motion-picture history.