4.2 How Do Infants and Children Develop Over Time?

|

|

a. Remember the key terms about how infants and children develop. |

List all of the boldface words and write down their definitions. |

b. Understand physical development in an infant. |

Summarize these motor and sensory changes in a table using your own words. |

c. Apply socio-emotional aspects of child development to real life. |

Describe the attachment style of an infant or child you know. |

d. Understand the four stages of cognitive development in children. |

Summarize the main aspects of development in each of the stages using your own words. |

e. Analyze the three stages of language development in childhood. |

Organize the three stages of development in a table that includes the typical age of the child and an example of what they might say. |

Have you ever seen a newborn baby? Do they seem completely helpless? In fact, babies arrive in the world with basic abilities that aid their survival. In infancy, beginning at birth and lasting between 18 and 24 months, babies can suck for nourishment and see the face of a caregiver who feeds them. They can cry when hungry, which makes parents want to feed them. Infants also smile and bond with caregivers, which develops attachments that aid their survival. And they can remember and learn. These abilities aid infants’ survival until childhood, which lasts from age 2 until about ages 11 to 14. Both infancy and childhood are times of great change across all three developmental domains: physical, cognitive, and socio-emotional.

Infants and Children Change Physically

As infants and children develop, the brain changes in two critical ways. First, myelinated axons form synapses with other neurons. Recall from Chapter 2 that myelin ensures efficient communication between neurons by functioning like the plastic that insulates electrical wires. The synaptic connections between neurons let regions of the brain communicate to process information. More of these connections develop than the infant brain will ever use, but this growth gives every brain the chance to adapt well to any environment. Second, over time and with experience, the synaptic connections change. Connections that are not used will decay and disappear. The loss of connections might seem like a bad thing, but it lets the brain process information more efficiently.

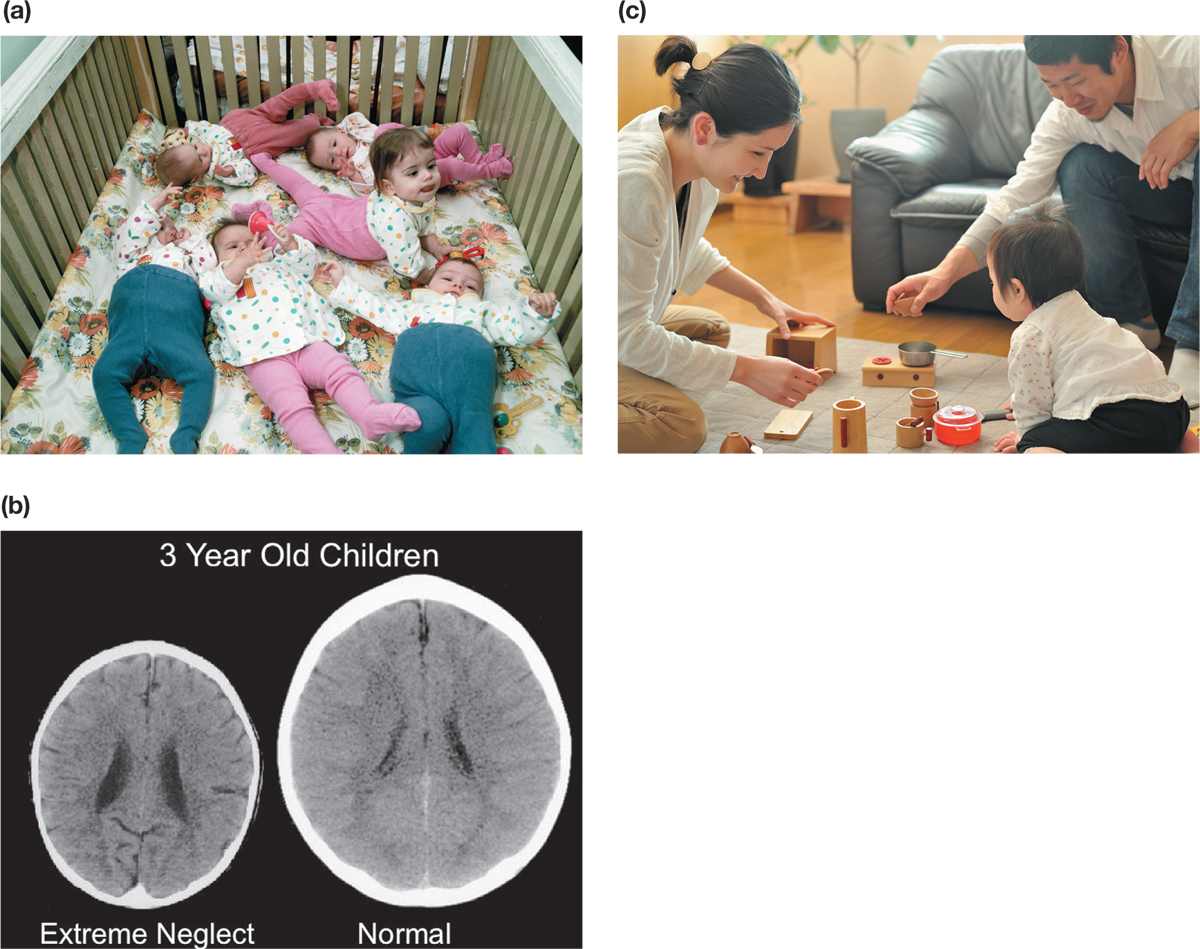

Unfortunately, sometimes infants and young children are raised in environments that do not stimulate their brains (Figure 4.8a). In these cases, very few synaptic connections are made. As a result, these under-stimulated brains will be less able to process complex information, solve problems, or allow the children to develop advanced language skills (Perry, 2002; Figure 4.8b, left side). But the reverse is also true: When infants and young children are able to explore the external world, and when they have ample opportunities to move, talk, and read, their brains are stimulated (Figure 4.8c). In short, when the brain is stimulated, the brain is encouraged to develop (Figure 4.8b, right side). And when the brain develops, it can support the individual’s rich physical, socio-emotional, and cognitive development.

FIGURE 4.8

Environmental Stimulation and Brain Development

(a) Some infants and children are raised in environments that provide little stimulation or comfort. (b) These images illustrate the impact of neglect on the developing brain. The brain scan on the left is from a 3-year-old child with minimal exposure to language, touch, and social interaction, who has a significantly smaller head. The brain scan on the right is from a healthy 3-year-old child with an average head size. (c) The best brain development takes place in environments with rich stimulation and comforting contact with caregivers.

INBORN REFLEXES Babies come into the world hardwired with basic motor reflexes that aid survival. For example, infants must eat in order to grow, and they are born with innate, unlearned reflexes that help them find food. When an infant is stroked at the corner of her mouth, she will show the rooting reflex. That is, she turns and opens her mouth in anticipation of food (Figure 4.9a). If she finds a nipple where she has turned, the infant will show the sucking reflex. Automatically closing her mouth on the nipple, she will begin to suck to eat (Figure 4.9b).

FIGURE 4.9

Infant Reflexes

Infants are born with innate abilities that help them survive, including the (a) rooting reflex, (b) sucking reflex, and (c) grasping reflex.

Another inborn reflex that aids survival is the grasping reflex (Figure 4.9c). If you stroke an infant’s palm, he automatically curls his fingers around the stroked area (see the Try It Yourself feature on p. 124). Some scholars believe that this survival mechanism persists from our prehistoric ancestors. Young primates need to be carried from place to place, so grasping their mothers is an adaptive reflex. Though such inborn reflexes help infants survive in the first months of life, being able to move on purpose is another matter entirely. Babies have to learn these motor skills.

TRY IT YOURSELF: Survival Reflexes

TRY IT YOURSELF: Survival Reflexes

If you know a newborn or a young infant, you can observe the innate survival reflexes. The baby can be anywhere from a day old to several months old, though babies show these reflexes less as they develop. Be sure to try this exercise when the baby is fully awake and alert and is in a comfortable and safe position—for example, nestled in a caretaker’s arms. But don’t freak out if the baby doesn’t display the expected results. Some deviation is perfectly acceptable. Anyone concerned about the development of a particular infant should seek the advice of a pediatrician.

Rooting reflex: Gently caress the baby’s cheek down to the corner of his mouth. The baby should turn his head toward the cheek that was stroked and might even open his mouth a bit.

Sucking reflex: If you have engaged the rooting reflex and the infant has opened his mouth, place the rubber tip of a pacifier or a baby bottle in the baby’s mouth. He may start to suck.

Grasping reflex: Place a finger in the palm of the baby’s hand, or gently stroke his palm, and the baby will close his fingers over his palm, perhaps around your finger.

MOTOR SKILLS Have you ever watched an infant trying to lift her head to look around? At first, the infant’s head wobbles on weak neck muscles. (This is why it is so important to cradle a baby’s head in your hand, so you can help control the head until the baby learns to do so herself.) It takes a lot of practice for the infant to learn to move her head—for example, to turn toward a voice she recognizes.

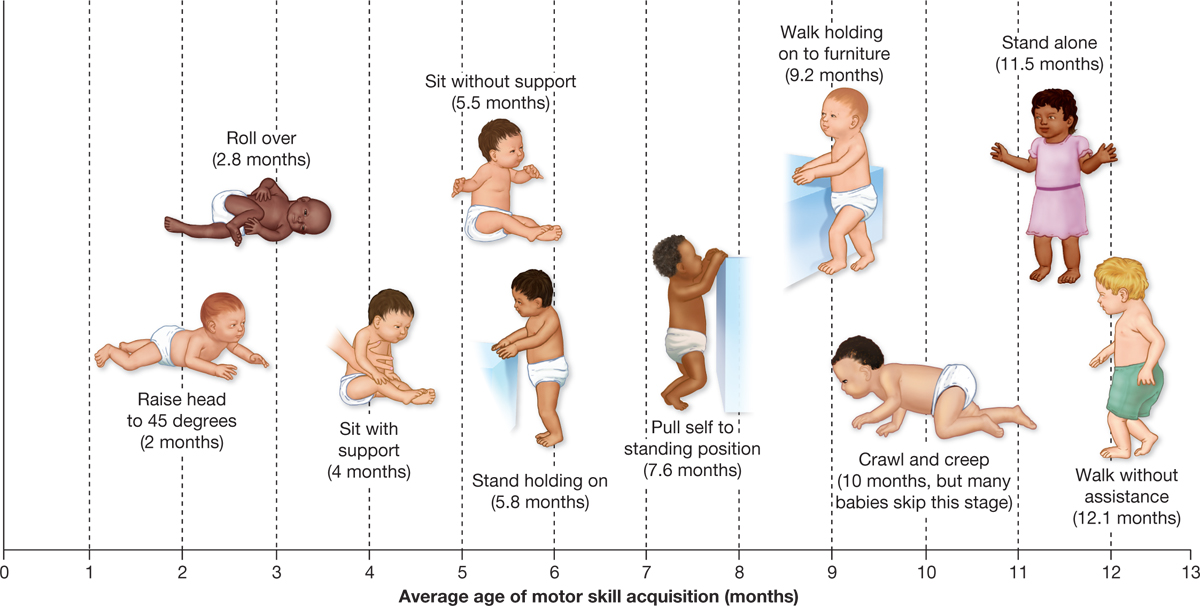

In the first years of life, children progress from moving their heads to sitting up, standing, and walking. The process of developing these motor skills is a sequence of steps that usually occur within a predictable range of ages. The process is called maturation (Figure 4.10). Maturation was originally thought to be determined only by nature, not by nurture. For an example of nature’s effects on development, consider that Brooke Greenberg could not walk primarily because of her biological deficits. But then, even in cases of normal brain development, occasionally an infant skips a step in maturation. The fact that not all babies crawl is an example of how nurture also affects maturation.

FIGURE 4.10

Physical Maturation and Learning to Walk

Usually, a human baby learns to walk without formal teaching, in a sequence that is typical of most humans. However, the age when a child develops a certain skill varies a lot, so the average age of acquisition is shown here. A child might deviate from this sequence—for example, by skipping the crawling phase—yet still develop normal walking abilities.

When infants sleep on their backs, they often skip the crawling phase. Perhaps infants who sleep on their backs do not develop the stomach muscles needed to crawl. In any case, pediatricians strongly recommend that infants sleep on their backs. Why? Since the mid-1980s, research has shown that placing infants on their backs for sleeping reduces the incidence of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Preventing SIDS is far more important than making sure that babies crawl before walking. And skipping the crawling phase does not affect long-term motor development! So some differences in maturation, caused by how an individual is nurtured, can be perfectly natural. You have to consider the circumstances.

DYNAMIC SYSTEMS PERSPECTIVE Development in physical, socio-emotional, and cognitive domains is a result of complex interactions. The factors involved are the person’s biology, the person’s active exploration of an environment, and the constant feedback provided within the person’s culture (Smith & Thelan, 2003). The dynamic systems theory of development can be seen in the way that children often achieve developmental milestones at different paces, depending on the culture in which they are raised (Figure 4.11).

FIGURE 4.11

Dynamic Systems Theory

Throughout life, every new behavior results from interactions between a person’s biology and that person’s cultural and environmental contexts.

As an example of the dynamic systems theory of development, one study (Super, 1976) focused on the motor development of Kipsigi infants in western Kenya. Kipsigi parents in the Kohwet village placed their babies in shallow holes in the ground so the babies could practice sitting upright. The parents also marched their babies around while placing their own arms under the babies’ arms, so the children could practice walking. These infants walked about 1 to 2 months earlier than American and European infants who spent a lot of time in cribs and playpens. But what about middle-class Kipsigi families who had moved to Westernized homes in a larger city? They let their infants both sleep in cribs and lie in playpens like their Western counterparts. However, they still deliberately taught their infants motor skills using traditional Kipsigi methods. These urban Kipsigi infants walked 2 weeks later than the rural infants in Kohwet but 1 week earlier than infants in Boston, Massachusetts. Clearly, the Kipsigi culture influences maturation differently depending on the environment.

SENSORY DEVELOPMENT To learn, infants need information. They get information from the world by hearing, seeing, smelling, tasting, and perceiving touch. Some of these sensory abilities are more fully developed at birth than others. The earliest fully developed sensory abilities are directly connected with the infant’s survival. For instance, 2-hour-old infants prefer sweet tastes to all other tastes (Rosenstein & Oster, 1988). This preference makes sense because breast milk is sweet, so infants are born with a built-in mechanism that makes them want to drink this nutritious milk. Infants also have a good sense of smell, especially for scents associated with feeding.

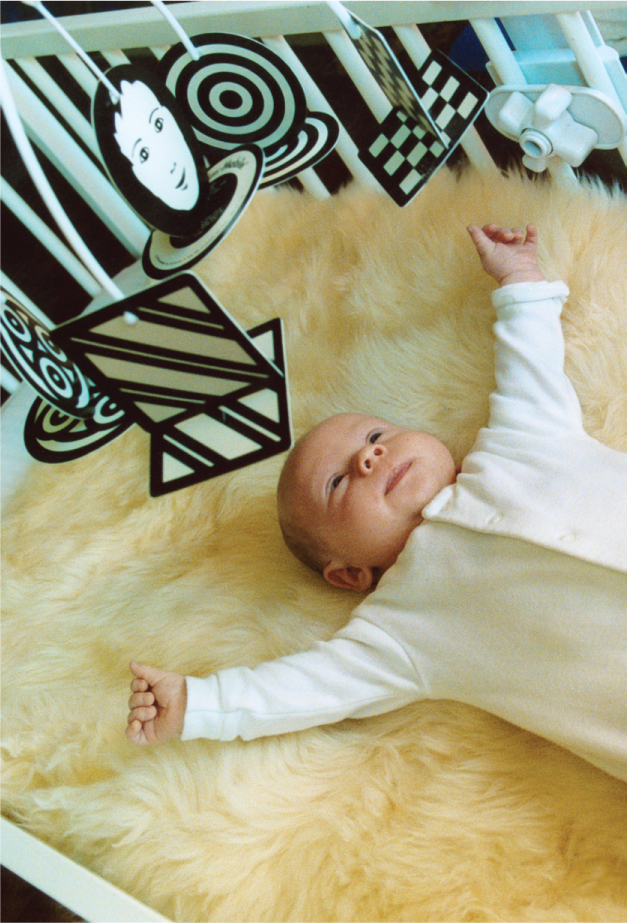

FIGURE 4.12

Babies Are Born Able to See High Contrast

The innate ability to see large blocks of black and white helps a baby survive. It lets the baby locate her mother’s nipple, which contrasts in color with the surrounding tissue, in order to eat.

When infants are born, they can also hear quite well. They startle at loud sounds and turn their heads in the direction of everyday sounds. Infants even hear well enough to prefer specific sounds. For instance, a newborn can change her sucking pattern in order to hear her mother’s voice (DeCasper & Fifer, 1980). The newborn’s ability to recognize and discriminate her mother’s voice makes sense because a fetus starts hearing that voice inside the womb at 4½ months. Infants’ abilities to recognize and locate sounds improve as they gain experience with objects and people and as the auditory cortex develops further. By the age of 6 months, babies hear nearly as well as adults (DeCasper & Spence, 1986).

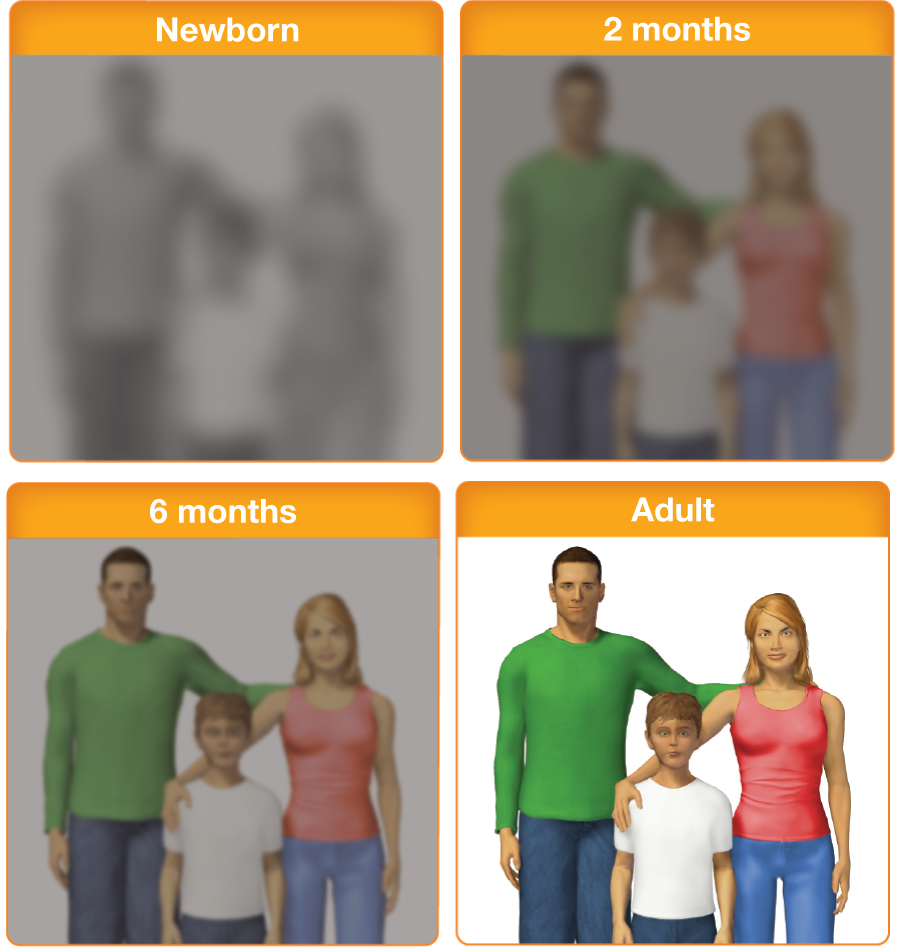

By contrast, newborns have quite poor vision. Initially they can see only about 8–12 inches from their heads and cannot make out differences between colors. They can see high-contrast patterns better than they see patches of gray (Fantz, 1966; Figure 4.12). These visual abilities are adaptive, because they let the infant focus on what is most important: the mother’s breast, which provides nutrition, and her face, which provides important social information.

By about 2 months, infants can see blue, green, and red. Their visual acuity for distant objects increases rapidly over the first 6 months (Figure 4.13; Teller, Morse, Borton, & Regal, 1974). As long as babies have access to rich visual experiences and the brain and parts of the eye develop normally, they can see in a way that is similar to adults when they are about a year old. Once again, development occurs thanks to complex interactions of dynamic systems.

FIGURE 4.13

Infants’ Visual Abilities Improve With Experience

Newborns have poor visual acuity and poor ability to see colors. These capacities improve rapidly over the first 6 months of life. At about a year of age, the infants’ visual abilities are similar to those of adults.

Infants and Children Change Socially and Emotionally

Humans are social animals. We spend a good part of our lives getting along with other people, or trying to. How do we learn how to do it? Infants and children develop socially and emotionally by interacting with others. Our early experiences with our primary caregivers—such as a mother, a father, a grandparent, a day care teacher—are critical for developing the bonds that are essential for socio-emotional development.

EARLY ATTACHMENT All infants—including those with brain damage and disabilities, such as Brooke Greenberg—have a fundamental need to form strong connections with caretakers. These connections help aid the infants’ survival. In order to develop these connections, all infants innately behave in ways that motivate adults to care for them over time and across situations (Bowlby, 1982).

FIGURE 4.14

Infant Attachment Behaviors

When newborns smile, it makes their caretakers want to care for them.

For example, an infant can cry immediately after birth. The crying causes caregivers to respond, typically by offering the newborn comfort, food, or both. In virtually every culture studied, men, women, and children raise the pitch of their voices when talking to babies. They know intuitively that babies can hear and will pay attention to high-pitched voices. In turn, the babies maintain eye contact with these people (Fernald, 1989; Vallabha, McClelland, Pons, Werker, & Amano, 2007). Eventually, between 4 and 6 weeks of age, infants display a first social smile, which creates powerful feelings of love in caregivers (Figure 4.14). When babies’ inborn behaviors create these connections, how do caregivers care for them?

During the late 1950s, psychologists believed infants mainly needed care in the form of food from their mothers. However, the psychologist Harry Harlow wondered if care was really about providing food, or about something else (Harlow & Harlow, 1966). To investigate this question, as you can see in the Scientific Thinking feature, Harlow placed infant rhesus monkeys in a cage with two surrogate “mothers.” One mother was made of wire and provided milk through a bottle. The second mother was made of soft terrycloth, but did not give milk. Harlow found that the monkeys approached the wire mother, the mother with food, only when they were hungry. The rest of the day, they clung to the cloth mother. To these monkeys, caring was really about having comforting contact, so they became attached to the soft, cloth mothers.

|

SCIENTIFIC THINKING: Attachment Is Due to Providing Contact |

Hypothesis: Infant monkeys will form an attachment to a surrogate mother that provides comfort.

Research Method: Infant rhesus monkeys were put in a cage with two different “mothers”:

1 One mother was made of soft cloth, but could not give milk. |

2 The other was made of hard wire, but could give milk. |

Results: The monkeys clung to the cloth mother and went to it for comfort in times of threat. The monkeys approached the mother with food only when they were hungry.

Conclusion: Infant monkeys will prefer and form an attachment to a surrogate mother that provides comfort over a wire surrogate mother that provides milk.

Note: Photographs are not available from the original experiments. These images are from the CBS television show Carousel, which filmed Harlow simulating versions of his experiments in 1962.

Question: How might these findings apply to understanding human children’s attachment to their caregivers?

To test this attachment, Harlow put a scary metal robot with flashing eyes and large teeth in the cage. Upon seeing the robot, the infants always ran to the cloth mother, never to the mother with food. Harlow repeatedly found that the infants were calmer, braver, and better adjusted overall when near the cloth mother. The mother-as-food theory of attachment was shown to be wrong. Harlow’s findings showed that comforting touch is critical in the socio-emotional development of infants.

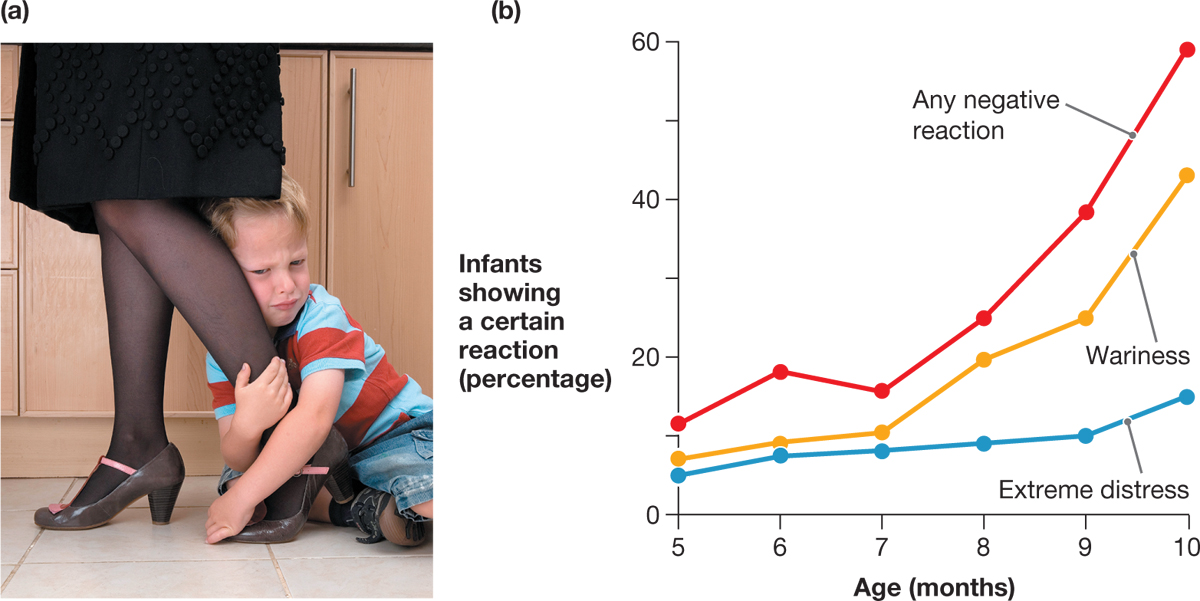

VARIATIONS IN ATTACHMENT Clearly, infants need physical closeness with and comfort from caregivers to develop socio-emotional bonds. At about 8 to 12 months, however, the infants begin to crawl or toddle and start to move away from caregivers. When they cannot see their attachment figures or are left with babysitters or strangers they don’t know, they often show signs of distress (Waters, Matas, & Sroufe, 1975; Figure 4.15). This phenomenon, separation anxiety, occurs in all human cultures. You’ve probably seen babies displaying separation anxiety. You can read about two typical situations in Has It Happened to You?

FIGURE 4.15

Separation Anxiety

(a) Beginning at about 8 months of age, infants show distress when separated from caregivers. (b) This separation anxiety increases dramatically as the infants approach their first year of life.

HAS IT HAPPENED TO YOU?

Separation Anxiety

Have you ever been in a room with a baby when the parent left for a minute? Or have you seen an infant left with a babysitter he didn’t know? How did the infant react in these situations? If he was 8–12 months old, he probably started to cry. The infant may have been experiencing separation anxiety, a condition of great distress when the caregiver is out of sight. It is a completely normal reaction for infants at this age. The infant was most likely fine as soon as a loved one comforted him. In fact, you were probably left more shaken by the experience than the infant was!

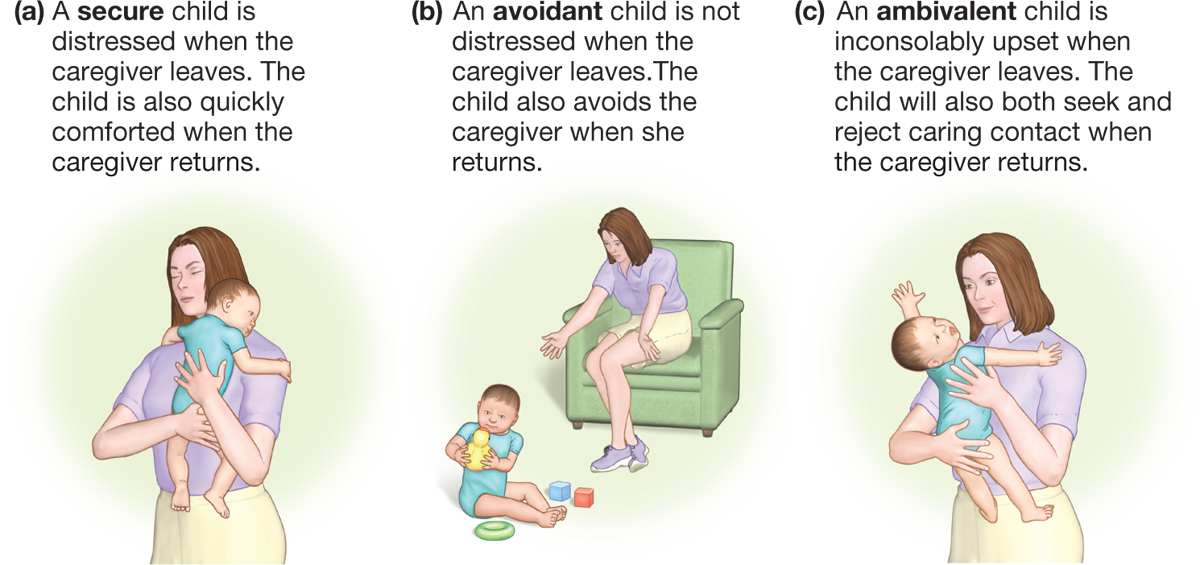

To study variations in infant attachment, the developmental psychologist Mary D. Salter Ainsworth created the strange-situation test. In a playroom, a child, a caregiver, and a friendly but unfamiliar adult participate in a series of separations and reunions between the child and each adult. The researchers observe the test through a one-way mirror in the laboratory and record the child’s responses to the caregiver and the stranger. The strange-situation test has revealed the three attachment styles children might have (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978).

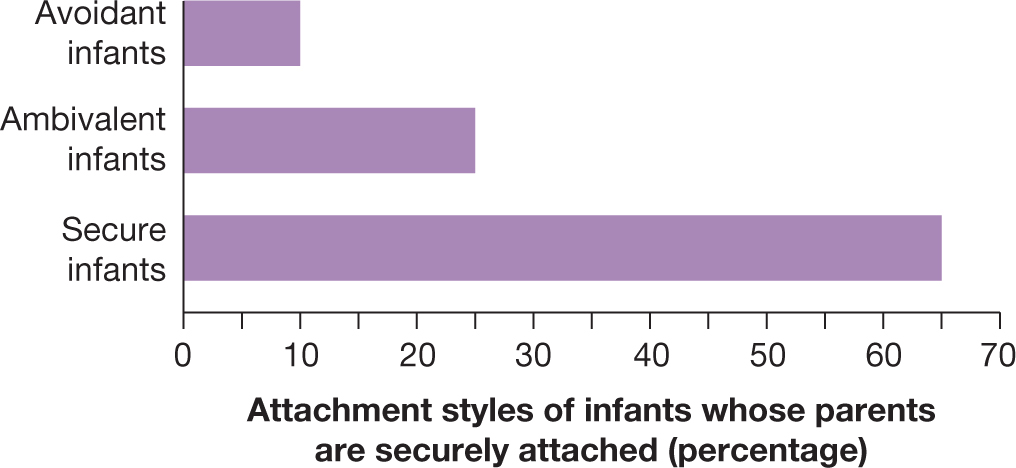

In secure attachment, the child is happy to play alone and is friendly to the stranger as long as the caregiver is present. When the caregiver leaves the playroom, leaving the child with the stranger, the child is distressed, whines or cries, and looks for the caregiver. When the caregiver returns, the child usually reaches out her arms to be picked up and is quickly comforted by the caregiver. The child then feels secure enough to return to playing (Figure 4.16a). Just as in Harlow’s findings, the caregiver is a source of security in times of distress. When parents have a secure attachment style, approximately 60 percent to 65 percent of their children also show secure attachment (Van IJzendoorn, 1995; Figure 4.17).

FIGURE 4.16

The Strange-Situation Test

This test is a method of exploring the attachment style of an infant or child. Attachment style is based on (1) how the child responds when the caregiver leaves her with a stranger, and (2) how the child responds when the caregiver returns. Shown here are (a) secure, (b) avoidant, and (c) ambivalent attachment styles.

FIGURE 4.17

Variations in Attachment Style

This chart breaks down what percentage of children (of parents who have a secure attachment style) show a secure, an avoidant, or an ambivalent attachment style.

The remaining 35 percent to 40 percent of children display one of the types of insecure attachment (see Figure 4.17). Those with avoidant attachment do not get upset or cry at all when the caregiver leaves. They may even prefer to play with the stranger rather than the caregiver during their time in the playroom. They may also avoid the caregiver upon the caregiver’s return (Figure 4.16b). Those with ambivalent attachment may cry a great deal when the caregiver leaves the room, yet both seek and reject caring contact when the caregiver returns and tries to calm them down (Figure 4.16c). Insecurely attached infants have learned that their caregiver is not available, or only inconsistently available, to soothe them when they are distressed. These children may be emotionally neglected or actively rejected by the people who take care of them.

Decades of research show that secure attachment is related to better socio-emotional functioning in childhood, better peer relations, and successful adjustment at school (e.g., Bohlin, Hagekull, & Rydell, 2000; Granot & Mayseless, 2001). In contrast, insecure attachments have been linked to poor outcomes later in life, such as depression and behavioral problems (e.g., Munson, McMahon, & Spieker, 2001). In cases of insecure attachment, interventions may help the caregivers learn the skills that increase the likelihood of forming secure attachments.

Infants and Children Change Cognitively

Two-year-old Rowen is in her car seat looking at a book. She asks her father, who is driving the car, “What’s this?” Her father replies, “Sorry, I am looking at the road. I can’t see what you see there in the backseat.” But Rowen doesn’t understand, so she keeps asking the same question. Young children cannot put themselves in another person’s shoes to understand what that person senses, thinks, or feels. However, through exchanges such as this one, children begin to learn about the world around them. Rowen, like most children, will eventually realize that other people’s perspectives are different from her own. In other words, she will develop cognitively.

DEVELOPING THEORY OF MIND Infants take a big step in cognitive development when they begin to understand who they are. We know a child has this ability if she recognizes herself in a mirror. If there is an infant in your life, you can follow the steps in Try It Yourself to see if he has developed this cognitive ability.

TRY IT YOURSELF: Development of Self-Recognition

TRY IT YOURSELF: Development of Self-Recognition

To determine whether an infant you know has developed the cognitive ability to recognize himself, gently place a red dot about the size of a dime on his nose, using red lipstick or face paint. Then, carefully, hold the infant in front of a mirror. If the infant can recognize himself, he will stare at the dot, touch it, or try to remove it. If the infant cannot recognize himself, he will not notice the red dot as unusual, so he won’t focus on it at all. If the infant does not show self-recognition, do this task again every few weeks. At a certain point, the infant will suddenly show this cognitive ability.

Once an infant becomes self-aware enough to recognize herself in a mirror, she can learn that her thoughts are different from those of other people (Gergely & Csibra, 2003; Sommerville & Woodward, 2005). The ability to understand that other people have minds and intentions is called theory of mind (Baldwin & Baird, 2001). In one study demonstrating theory of mind in infants, an adult begins handing a toy to an infant, but then stops. On some trials, the adult acts unwilling to hand over the toy, teasing the infant with the toy or playing with it herself. On other trials, the adult becomes unable to hand it over, “accidentally” dropping it or being distracted by a ringing telephone. Infants older than 9 months showed greater signs of impatience—for example, reaching for the toy—when the adult was unwilling than when the adult was unable (Behne, Carpenter, Call, & Tomasello, 2005).

This and other studies (e.g., Onishi & Baillargeon, 2005) provide strong evidence that children begin to read the intentions of other people in the first year of life. By the end of the second year, perhaps even by 13 to 15 months of age, children become very good at reading intentions (Baillargeon, Li, Ng, & Yuan, 2009). In other words, even though preschool-age children tend to view the world based only on their own perspectives, they have the cognitive ability to understand others’ perspectives. And as infants and children acquire theory of mind, they develop the ability to think in increasingly sophisticated ways.

PIAGET’S THEORY OF COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT As the movie Boyhood opens, the mother of 6-year-old Mason is scolding him. He ruined his teacher’s pencil sharpener by putting rocks in it. Mason’s mother can’t understand what he was thinking. “What were you going to do with sharpened rocks?” she asks. “I was trying to make arrowheads for my rock collection,” he explains. If you have ever spent time with a child, you may recognize this explanation as an example of “child logic.” This kind of logic makes no sense to an adult, but to a child it makes perfect sense.

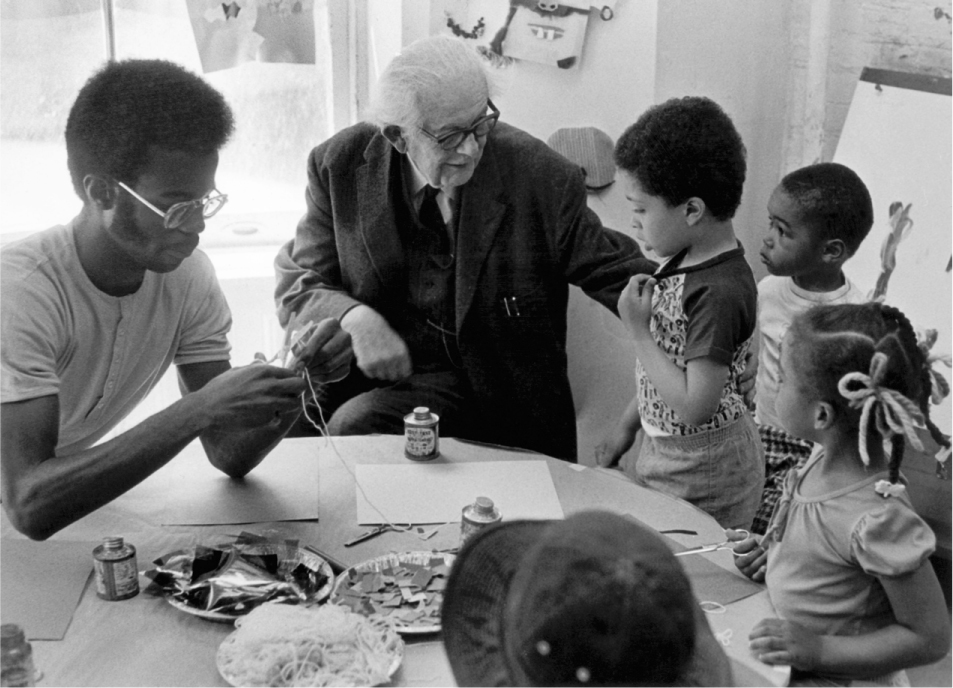

FIGURE 4.18

Jean Piaget

Piaget’s work with young children revealed that thinking becomes more sophisticated as we progress through several stages of cognitive development.

The developmental psychologist Jean Piaget investigated how children’s thinking changes as they develop (Figure 4.18). By exploring the mental abilities of his own three children and many others, Piaget discovered that children’s minds truly do work in a different way than those of adults.

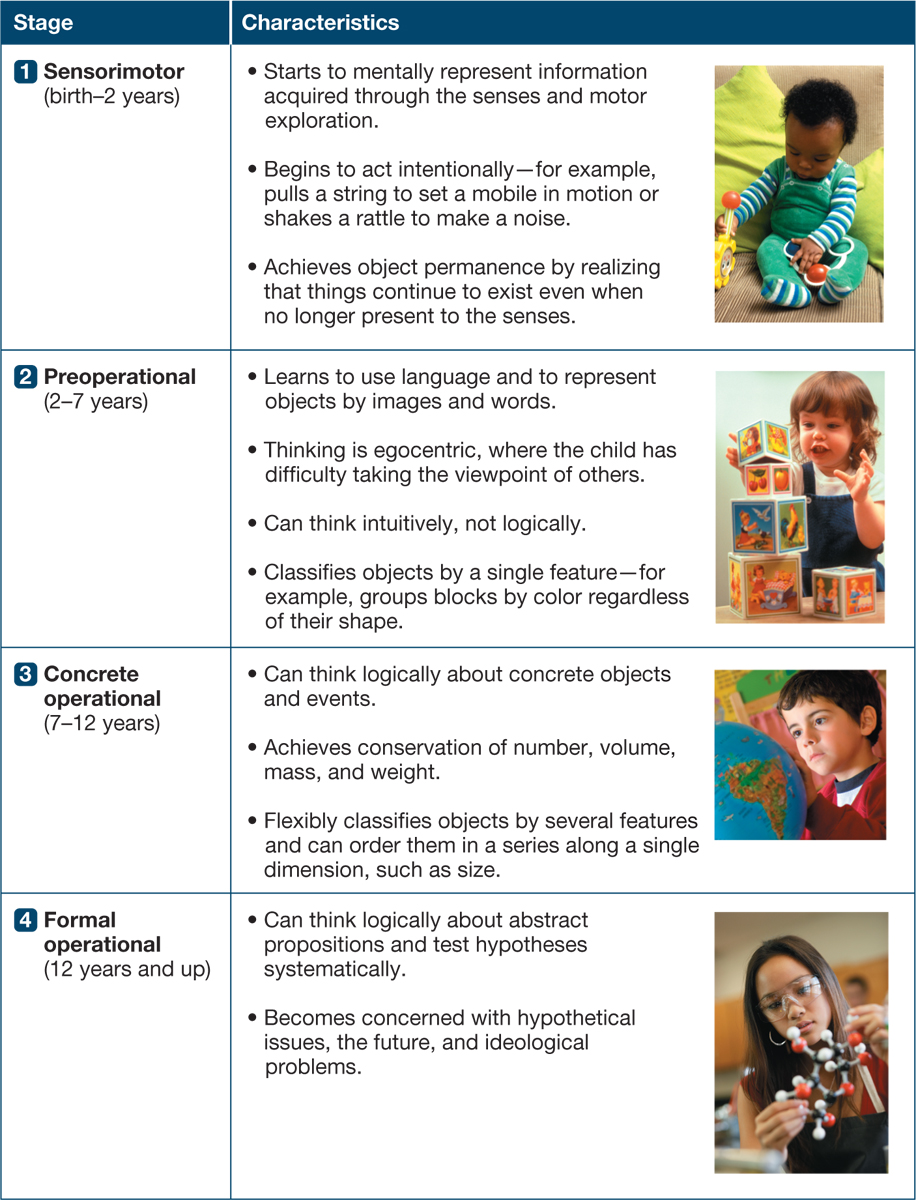

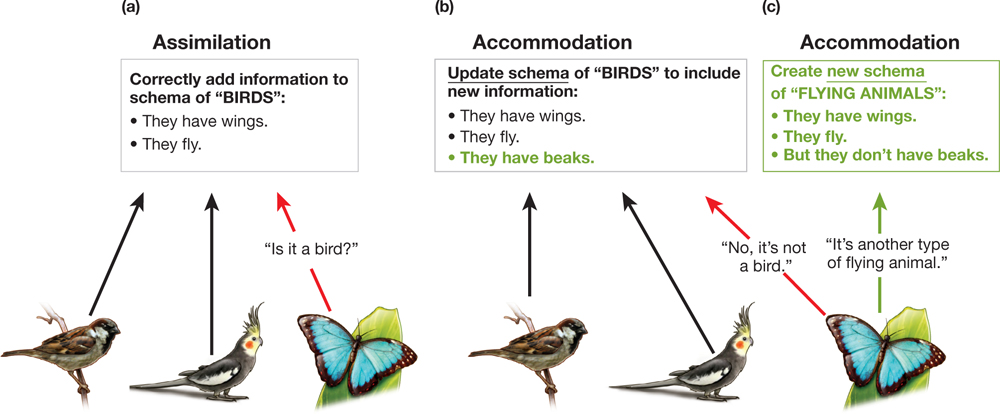

Specifically, Piaget proposed that we change how we think as we form new schemas, or ways of thinking about how the world works. Piaget described two ways that we develop a schema, which are shown in the Learning Tip. During assimilation, we place a new experience into an existing schema, which is a mental representation about that information. During accommodation, we create a new schema, or dramatically alter an existing one to include new information that otherwise would not fit into the schema. For example, a 2-year-old might see a butterfly for the first time and shout, “Bird!” After all, a butterfly has wings and flies just like birds. But the toddler’s parent says, “No, honey, that’s a butterfly! See, it doesn’t have a beak!” Now the child must accommodate this new information about beaks into the existing schema about birds. And he must also accommodate by creating a new schema about flying animals. The constant repetition of assimilation and accommodation allows a child to develop increasingly complex schemas over time. These schemas allow the child to think in more-sophisticated ways. Piaget’s research became the basis for his influential theory that children go through four progressively complex stages of cognitive development, which are summarized in Figure 4.19.

FIGURE 4.19

Piaget’s Four Stages of Cognitive Development

Piaget described how children’s thinking abilities are characterized across four stages of cognitive development.

LEARNING TIP: Assimilation and Accommodation

LEARNING TIP: Assimilation and Accommodation

Use this graphic to help you understand the difference between the two ways that thinking develops as described by Jean Piaget.

SENSORIMOTOR STAGE: BIRTH TO 2 YEARS According to Piaget, children from birth until about age 2 are in the sensorimotor stage of cognitive development. During this period, they acquire information primarily through their senses and motor exploration. For example, they first learn reflexively, by sucking on a nipple, grasping a finger, or seeing a face.

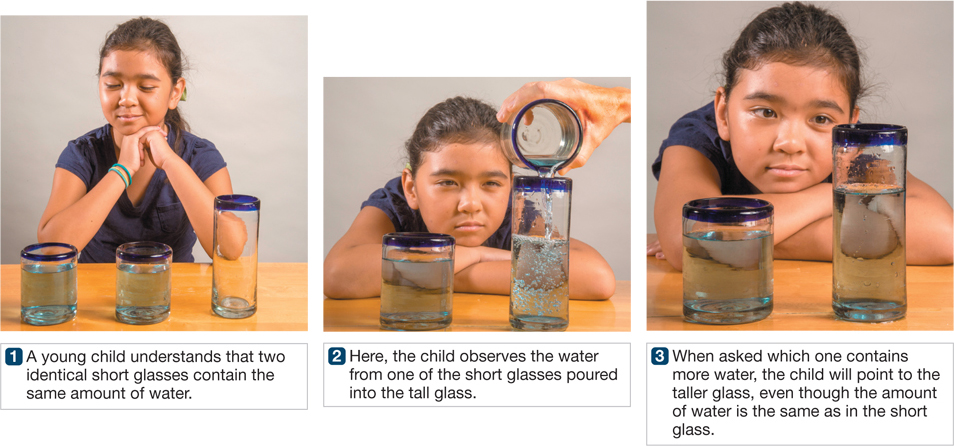

FIGURE 4.20

Conservation Task Based on Volume

In the preoperational stage, according to Piaget, children reason intuitively, not logically. As a result, these children cannot yet understand the concept of conservation, which is shown here in a task focusing on the volume of a liquid.

As infants begin to control their motor movements, they develop their first schemas. These mental representations contain information about actions that can be performed on certain kinds of objects. For instance, the sucking reflex lets the infant realize she can suck other things, such as a bottle, a finger, a toy, or a blanket. Piaget described sucking other objects as an example of assimilation to the schema of sucking. But sucking a toy or a blanket does not result in the same experience as the reflexive sucking of a nipple. The difference between these experiences leads the child to alter the sucking schema to include new experiences and information. For example, while sucking a blanket, she may create a new schema that includes using less force than sucking on a bottle. She uses the process of accommodation to create this new schema.

According to Piaget, one important cognitive concept developed in this stage is object permanence—the understanding that an object continues to exist even when it is hidden from view. Piaget noted that until 9 months of age, most infants will not search for objects they have seen being hidden under a blanket. At around 9 months, they will look for the hidden object by picking up the blanket. A child’s full comprehension of object permanence was, for Piaget, one key accomplishment of the sensorimotor period.

PREOPERATIONAL STAGE: 2 TO 7 YEARS According to Piaget, children from about 2 to 7 years of age can begin to think about objects not in their immediate view. They have developed mental representations of objects that are not in view. During this preoperational stage, children begin to think symbolically. For example, they can pretend that a stick is a sword or a wand. However, Piaget believed that children at this stage cannot think operationally—in other words, they cannot imagine the logical outcomes of performing certain actions on certain objects. Instead, they use intuitive reasoning based on superficial appearances.

For instance, children at this stage have no understanding of the law of conservation. This law states that even if the appearance of a substance changes in one dimension, the properties of that substance remain unchanged. For example, if you pour a short, wide glass of water into a tall, narrow glass, the amount of water does not change. But if you ask children in the preoperational stage which glass contains more, they will pick the tall, narrow glass because the water is at a higher level. The children will make this error even when they have seen someone pour the same amount of water into each glass or when they pour the liquid themselves. They cannot understand that it is the narrower diameter of the taller glass that makes the water level higher (Figure 4.20).

The lack of conservation skills is thought to be due to a key cognitive limitation of the preoperational stage: centration. This limitation occurs when a child cannot think about more than one aspect of a problem at a time. The child “centers” on only one detail of the problem, so his ability to think logically is limited.

FIGURE 4.21

Egocentrism

This toddler is playing hide and seek with her mother. Because the toddler’s head is in the box and she cannot see the mother, she believes that the mother also cannot see her. She is definitely in the preoperational stage.

Another cognitive characteristic of the preoperational period is egocentrism. Preoperational thinkers generally view the world through their own experiences. They can understand how others feel, and they are able to care about others, but their thought processes tend to revolve around their own perspectives. For example, a 2-year-old may play hide-and-seek by placing a box over her head, believing that if she cannot see other people, other people cannot see her (Figure 4.21). Instead of viewing this egocentric thinking as a limitation, modern scholars agree with Piaget that such “immature” skills prepare children to take special note of their immediate surroundings and learn as much as they can about how their own minds and bodies interact with the world. A clear egocentric focus prevents them from trying to expand their schemas too much before they understand how they think about and understand their own experiences (Bjorklund, 2007).

CONCRETE OPERATIONAL STAGE: 7 TO 12 YEARS At about 7 years of age, according to Piaget, children enter the concrete operational stage. They remain in this stage until adolescence. Piaget believed that humans do not develop logic until they begin to think about and understand operations. A classic operation is an action that can be undone: A light can be turned on and off, a stick can be moved across the table and then moved back, and so on. According to Piaget, when children are able to understand that an action is reversible, they can begin to understand concepts such as conservation. Children in this stage are not fooled by superficial transformations, such as how the volume of liquid can look different in glasses of varying size. Instead, they can reason logically about problems.

Although using operations is the beginning of logical thinking, Piaget believed that children at this stage reason only about concrete things. That is, they reason about objects they can act on in the world. They are not yet able to reason abstractly, or hypothetically, about what might be possible. Because they cannot do operations “in their heads,” children in first, second, and third grades often use objects to do math. They use their fingers to add and subtract, and they group objects, such as tokens, to multiply and divide. By using concrete information, children in this stage can think in much more logical ways than children in the preoperational stage. However, according to Piaget, they cannot truly engage in sophisticated abstract thinking until they reach adolescence.

FORMAL OPERATIONAL STAGE: 12 YEARS TO ADULTHOOD Piaget’s final stage of cognitive development is the formal operational stage. Here, people can reason in sophisticated, abstract ways. Formal operations involve critical thinking, characterized by the ability to form a hypothesis about something and test the hypothesis through logic. Critical thinking also involves using information to systematically find answers to problems. To study this ability, Piaget gave teenagers and younger children four flasks of colorless liquid and one flask of colored liquid. He then explained that the colored liquid could be obtained by combining two of the colorless liquids. Adolescents, he found, systematically try different combinations to obtain the correct result, whereas younger children just randomly combine liquids. Adolescents are also able to consider abstract notions and think about many viewpoints at once. Lastly, this kind of thinking is characterized by an ability to envision the future and predict the consequences of certain actions.

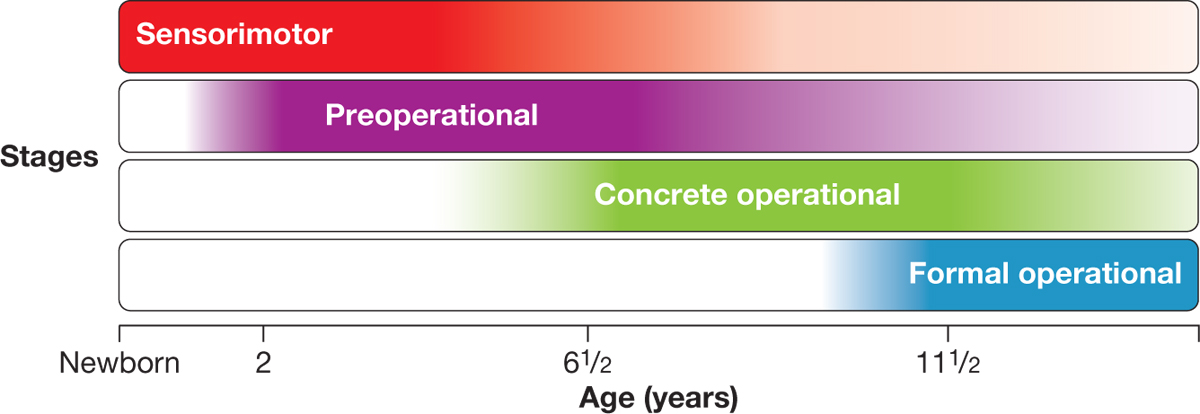

NEW WAYS OF THINKING ABOUT PIAGET’S THEORY Piaget’s theory revolutionized the understanding of cognitive development. And he was right about many things. For example, infants do learn about the world through sensorimotor exploration. Also, people do move from intuitive, illogical thinking to a more logical understanding of the world. However, modern research has revealed that we have to consider Piaget’s theory more flexibly.

For example, we now know that Piaget underestimated the ages at which certain skills develop. When contemporary researchers use age-appropriate methods they find that object permanence develops in the first few months of life, rather than at 8 or 9 months of age, as Piaget thought (Baillargeon, 1987). In his various studies, Piaget may have confused infants’ cognitive abilities with their physical capabilities. Because of this, he may have underestimated the age at which some thinking skills develop. For example, infants may not be able to grasp a hidden object, but they may still understand that it exists.

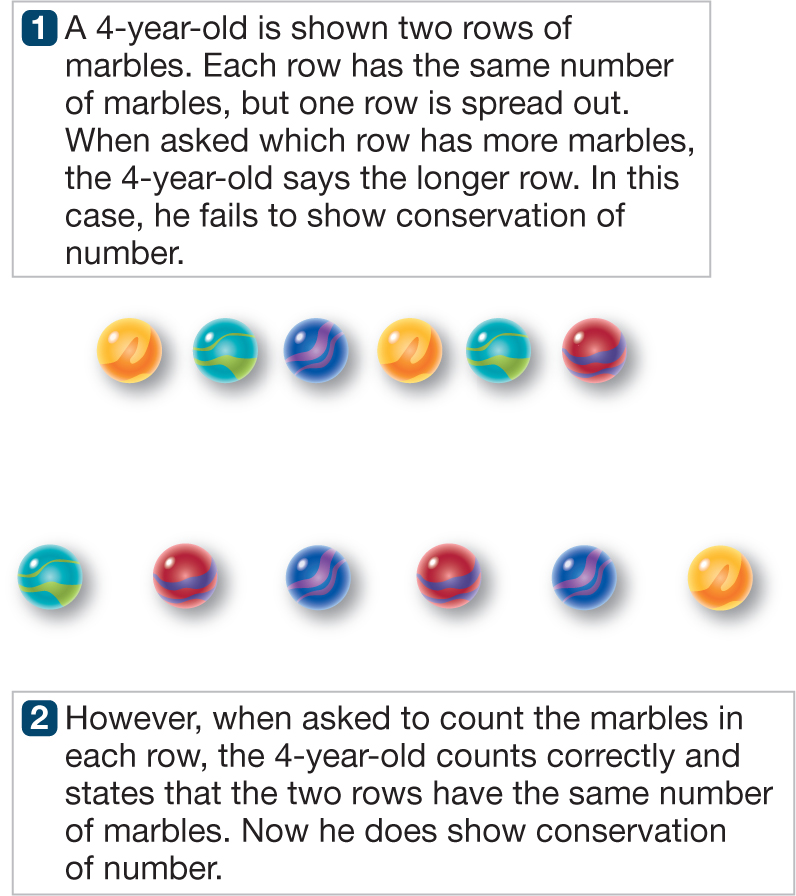

In addition, psychologists now think of cognitive development in terms of trends rather than strict stages. People gradually shift from one or more ways of thinking to other ways of thinking, so they may exhibit skills from different stages simultaneously (Figure 4.22). For example, while a certain child might not understand the conservation of volume (see Figure 4.20), she may be able to perform a conservation task based on number (Figure 4.23). This view of cognitive development is consistent with our understanding of brain development. Cognitive development may not necessarily follow strict and uniform stages, because different areas of the brain are responsible for different skills (Bidell & Fischer, 1995; Case, 1992; Fischer, 1980).

FIGURE 4.22

Trends in Cognitive Development

Modern interpretations view Piaget’s theory in terms of trends, not rigid stages. Children shift gradually in their thinking over a wider range of ages than previously thought, and they can demonstrate thinking skills of more than one stage at a time.

FIGURE 4.23

Conservation Task Based on Number

When a task is performed in an age-appropriate manner, children are able to show conservation of number much earlier than they can show conservation of volume (see Figure 4.20).

Language Develops in an Orderly Way

Recall that 19-year-old Brooke Greenberg, whose physical and mental development stopped when she was a toddler, could communicate only by making infant-like sounds. The ability to speak in sentences develops as the brain changes and as cognitive abilities become more sophisticated. It is important to recognize that as children develop social skills, they also improve their language abilities. Thanks to language, we can live in complex societies where our ability to communicate helps us learn the history, rules, and values of our culture. Language also helps us communicate across cultures and learn much more than other animals can. How do we develop our remarkable ability to use language?

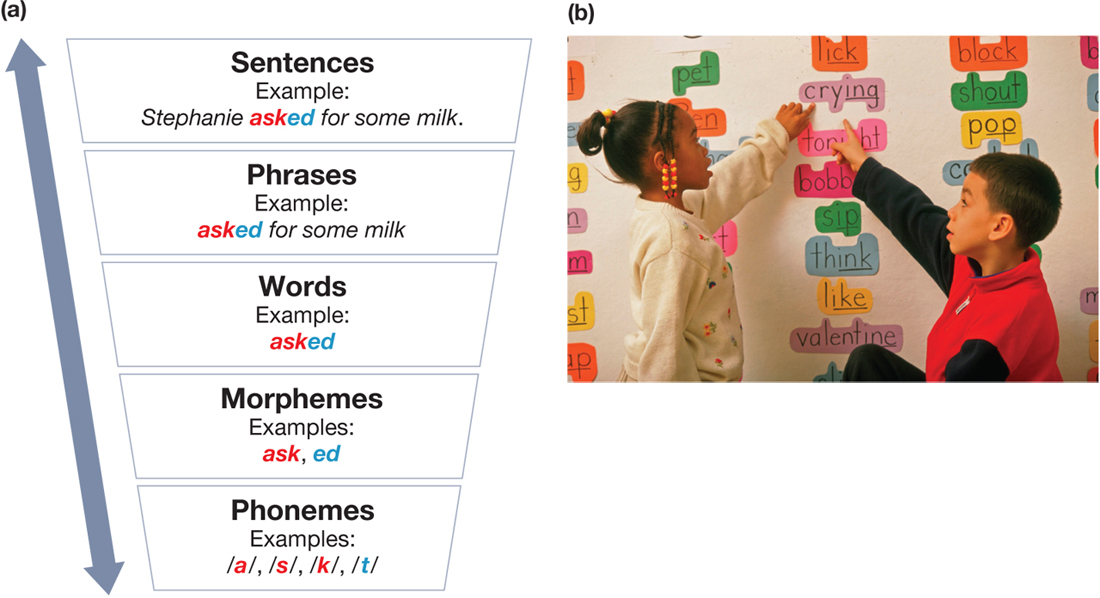

FIGURE 4.24

Organization of Language

(a) Language is organized hierarchically. Sentences and phrases are created from words, words are created from morphemes, and morphemes are created from phonemes. (b) In learning to read, these children are combining phonemes into morphemes.

FROM ZERO TO 60,000 Language is a system of using sounds and symbols according to grammatical rules. It can be viewed as a hierarchical structure. Sentences can be broken down into smaller units, called phrases, and phrases can be broken down into words (Figure 4.24a). Each word consists of one or more morphemes (the smallest units that have meaning, including suffixes and prefixes). Each morpheme consists of one or more phonemes (basic sounds; Figure 4.24b). For example, the word asked has two morphemes (“ask” and “ed”) and four phonemes (the sounds you make when you say the word: /a/s/k/t/). Syntax is the system of rules about how words are combined into phrases and how phrases are combined to make sentences. For example, English syntax dictates that we say Stephanie asked for some milk, not Stephanie some milk for asked.

Infants are born ready to learn language. In fact, the language or languages that mothers speak during pregnancy influence the listening preferences of newborns. For instance, Canadian newborns whose mothers spoke only English during pregnancy showed a strong preference for sentences in English as compared with sentences in Tagalog, a major language of the Philippines. Newborns of mothers who spoke both Tagalog and English during pregnancy paid attention to both languages (Byers-Heinlein, Burns, & Werker, 2010). Further, up to 6 months of age, a baby can discriminate all the speech sounds that occur in all languages, even if the sounds do not occur in the language spoken in the baby’s home (Kuhl, 2006; Kuhl et al., 2006; Kuhl, Tsao, & Liu, 2003).

From hearing sounds immediately after birth and then learning the sounds of their own languages, babies develop the ability to speak. Without working very hard at it, humans appear to go from babbling as babies to employing a full vocabulary of about 60,000 words as adults. Learning to speak follows a distinct path. During the first months of life, newborns’ actions—crying, fussing, eating, and breathing—generate all their sounds. In other words, babies’ first verbal sounds are cries, gurgles, grunts, and breaths. From 3 to 5 months, they begin to coo and laugh. From 5 to 7 months, they begin babbling, using consonants and vowels. From 7 to 8 months, they babble in syllables (ba-ba-ba, dee-dee-dee).

By the end of their first year, infants around the world are usually saying their first words. These first words typically combine phonemes into morphemes to label items in their environment (kitty, milk), simple action words (go, up, sit), quantifiers (all gone! more!), qualities or adjectives (hot), socially interactive words (bye, hello, yes, no), and even internal states (boo-boo after being hurt; Pinker, 1984). Thus even very young children use words to perform a wide range of communicative functions. They name, comment, and request.

By about 18 to 24 months, children’s vocabularies start to grow rapidly. They put words together and form basic sentences of roughly two words. Though these mini-sentences are missing some words, they have what is known as syntax. Typically, the word order indicates what has happened or should happen: For example, “Throw ball. All gone” translates as I threw the ball, and now it’s gone. The psychologist Roger Brown called these utterances telegraphic speech because the children speak as if they are sending a telegram. They put together bare-bones words according to correct syntax (Brown, 1973).

As children use language in increasingly sophisticated ways, they sometimes overapply regular grammar rules. This tendency is called overregularization. For example, when children learn that adding -ed makes a verb past tense, they add –ed to every verb, even verbs that do not follow that rule. Thus they may say “runned” or “holded” even though they may have said “ran” or “held” at a younger age. This trend usually lasts through the early elementary school years, when children begin to master irregular forms of words. Such overregularizations reflect an important aspect of language acquisition: Children are not simply repeating what they have heard others say. After all, they most likely have not heard anyone say “runned.” Instead, these errors occur because children recognize patterns in spoken grammar and then apply the patterns to new sentences they never heard before (Marcus, 1996; Marcus et al., 1992). Of course, as children gain experience using language with other people, they usually learn to correct these mistakes. By about age 6, children use language nearly as well as most adults. Their vocabulary will continue to grow throughout their lives.

|

BEING A CRITICAL CONSUMER: |

Daniel came home from work and was looking forward to spending some time with his 12-month-old daughter, Amy. He was enjoying watching her change every day. And it was particularly interesting to connect all the information about developmental psychology to what Amy was doing. A few months ago, Daniel had tested her motor reflexes. And a few weeks ago he had investigated whether she was showing any stranger anxiety. I won’t try that one again, Daniel thought. Boy, did she scream when I introduced her to the new sitter! Just last week, Daniel realized that Amy had acquired the skill of object permanence when she crawled to get a ball that had rolled out of sight under the couch. But although Amy was babbling a lot, she wasn’t speaking many words yet. Daniel wondered whether he could do anything to help Amy learn to speak. He remembered having seen lots of advertisements for media that claimed to teach babies how to talk. Daniel thought to himself, I have a little time before Mom brings Amy home. I’ll hop on the Web and see what I can find.

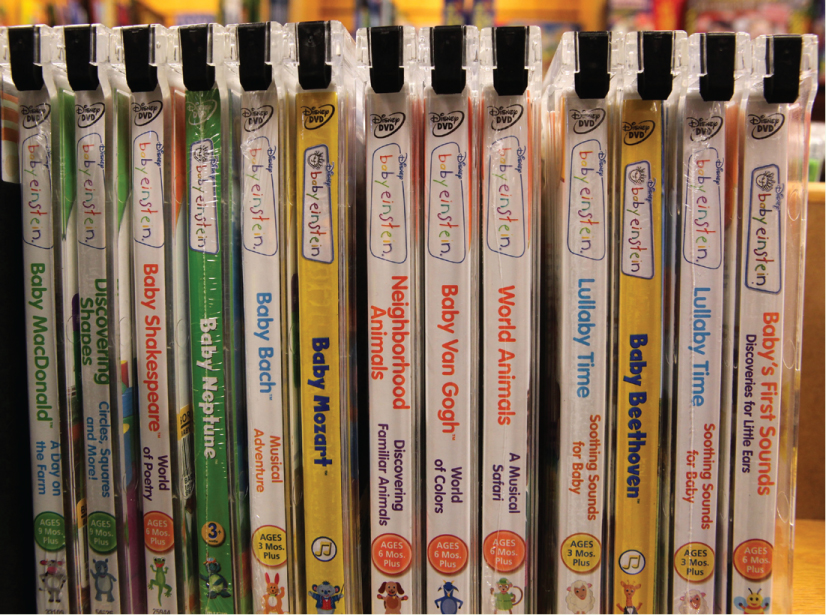

Daniel entered some search terms and immediately found information that seemed helpful. One product was a DVD from a well-respected company, which said it “introduces little ones to words and sign language.” Next to the picture of the DVD, Daniel saw testimonials from parents describing the positive effects of the product on their kids. Daniel thought about this information. Even the name of the product, “Baby Einstein,” suggests there is something genius-inducing about it!

As Daniel continued his search, he found one study stating that 76 out of the top 100 best-selling baby DVDs on Amazon made similar types of educational claims. Another article stated that educational DVDs geared toward infants earn about $500 million in sales every year. OK, so the companies advertise these products as educational. And they sell a lot of them. But do these products really work? Or are parents wasting their money? Or worse still, might these products adversely affect children? I need some scientific evidence!

Daniel decided to dig deeper. This time, he used Google Scholar to explore whether products like these would help kids learn to talk. Soon enough, he found believable information from scientific journals, not product advertisements. One study of 1,000 infants aged 7–16 months revealed that kids who watched the educational DVDs had poorer ability to understand spoken language than those kids who did not watch the DVDs. In fact, these infants knew about 6–8 fewer words for every hour that they watched the DVDs. Another study found that children between 12 and 15 months of age who watched the Baby Wordsworth DVD five times over two weeks showed no effect on either ability to understand or speak language.

It seems pretty clear that the educational claims these DVDs make are just for marketing purposes. It looks like they won’t help Amy learn to talk. I wonder what will help? In his searches for journal articles, Daniel repeatedly saw that the amount of time an infant was read to did predict language abilities. In addition, when caregivers actively read with children, pointing out pictures and words and discussing the story, these social interactions seemed to better support development of language skills than watching “educational” DVDs. That decides it for me! We are going to read books together every day for at least 20 minutes. And I will talk with Amy about the pictures on the pages and point out the various words to her. That way, I can do my part to help her learn to talk. And it will be fun to spend that time with her!

QUESTION

What was the DVD advertisement trying to get Daniel and other parents to believe? What evidence did Daniel find to refute these claims? What do you think is the most reasonable conclusion about the educational DVDs?

|

|

■ Infants are born with innate reflexes, but through experiences we learn to move and process sensory information.

■ Forming strong attachments with caregivers helps infants develop appropriate social interactions and emotion regulation.

■ Infants’ and children’s cognitive abilities become more advanced with time and experience as they move through four stages of cognitive development.

■ Children develop language skills starting with the production of phonemes and eventually moving to speaking full sentences.

LEARNING GOALS

LEARNING GOALS READING ACTIVITIES

READING ACTIVITIES

4.2 CHECKPOINT:

4.2 CHECKPOINT: