4.3 How Do Adolescents Develop?

|

|

a. Remember the key terms related to adolescent development. |

List all of the boldface words and write down their definitions. |

b. Understand the physical changes in puberty. |

Summarize the changes in secondary and primary sex characteristics and when they occur in boys and girls, using your own words. |

c. Apply socio-emotional aspects of development to your own adolescence. |

Provide a description of the development of your sense of identity, including your ethnic identity and how you relate to family and friends. |

d. Analyze one aspect of cognitive development, a moral dilemma, in your own life. |

Describe three ways you could reason morally about a dilemma in your life based on Kohlberg’s theory. |

Do you remember when you began to go through adolescence? We all go through this stage, unless there is some problem with our physical development (as was the case with Brooke Greenberg, discussed in the chapter opener). This period starts at the end of childhood, about age 11 through 14, and lasts until about age 18 or 21. Your adolescent body was changing in major ways, growing larger and sometimes doing things beyond your control. Your emotions may have seemed uncontrollable as well. And you suddenly may have felt wildly attracted to people you never thought about before.

As children approach adolescence, all aspects of the self are changing. Physical changes occur, socio-emotional changes emerge as part of evolving relationships with parents and peers, and cognitive changes arise as part of the potential emergence of critical and analytical thinking. Taken together, changes in these three domains lay the foundation for the development of a sense of personal identity.

Adolescents Develop Physically

Physically, adolescence is characterized by the onset of sexual maturity and the ability to reproduce. Puberty, a roughly two-year developmental period, marks the beginning of adolescence. The first signs of puberty typically begin at about age 8 for girls and at about age 9 or 10 for boys. Most girls complete pubertal development by age 16 (Ge, Natsuaki, Neiderhiser, & Reiss, 2007; Herman-Giddens, Wang, & Koch, 2001; Sun et al., 2005) and boys finish by the age of 18 (Lee, 1980).

PUBERTY When you were around 10 or 12 years old, did you seem to grow overnight? This adolescent growth spurt—a rapid, hormonally driven increase in height and weight—is an obvious dividing line between childhood and puberty. During puberty, hormone levels increase throughout the body, stimulating many physical changes that allow us to develop into sexually mature adults.

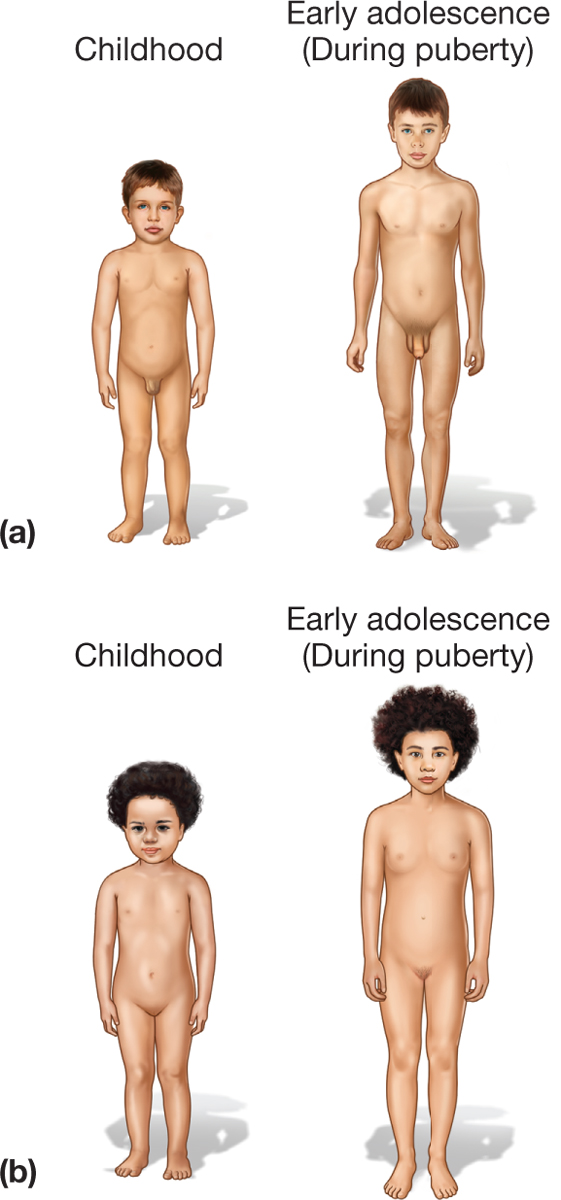

FIGURE 4.25

Physical Development During Adolescence

These graphics show how adolescents develop secondary sex characteristics during puberty that change them from looking like children to looking like adults. (a) Boys develop darker and thicker body hair on the legs, in the armpits, in the pubic area, and on the face and chest. They grow taller and gain muscle mass. Their jaw becomes more angular. (b) Girls develop darker and thicker body hair on the legs, in the armpits, and in the pubic area. They become taller, they grow breasts, their waists become more defined, and they gain more fat on their hips.

The first changes that occur are the secondary sex characteristics (Figure 4.25). Boys and girls start to experience greater growth of body hair, first as darker and thicker hair on the legs, then under the arms, then as pubic hair (Marshall & Tanner), then in other places. Boys’ muscle mass increases, their voices deepen, and their jaws become more angular. Girls lose baby fat on their bellies as their waists become more defined, and they also develop fat deposits on the hips and breasts (Lee, 1980). You will learn more about puberty, and how these changes affect the sexual desires of adolescents, in Chapter 10.

Puberty also brings the development of the primary sex characteristics. That is, the male and female external genitals and internal sex organs mature, menstruation begins in girls, and sperm develops in boys. These physical changes result in adolescents’ becoming sexually mature and able to reproduce.

Puberty may seem to be purely physical, but it is affected by environment. For example, a girl who lives in a stressful environment or has insecure attachments to caregivers is likely to begin menstruating earlier than a girl in a peaceful, secure environment (Wierson, Long, & Forehand, 1993). This finding suggests that a girl’s body responds to stress as a threat. Because the body feels threatened, it speeds up the ability to reproduce in order to continue the girl’s gene pool. Thus environmental forces trigger hormonal changes, which send the girl into puberty (Belsky, Houts, & Fearon, 2010). Because boys do not have an easily identifiable pubertal event like menstruation in girls, we know less about the effects of environment on puberty in boys. Boys and girls experience similar changes in brain development during adolescence, however, so researchers are able to identify a few key characteristics of the teenage brain.

BRAIN CHANGES DURING ADOLESCENCE While teenagers are experiencing pubertal changes, their brains also are in an important phase of reorganization. Synaptic connections are being refined, and gray matter is increasing. However, the frontal cortex of the brain is not fully developed until the early 20s. An adolescent’s limbic system—the motivational and emotional center of the brain—tends to be more active than the frontal cortex. As a result, although teenagers are able to think critically, they often have a difficult time doing so. Instead, they are more likely to act irrationally and engage in risky behaviors than adults are (Blakemore & Choudhury, 2006; Casey, Jones, & Somerville, 2011). Because teenagers have the ability to understand the consequences of their actions, it is important to help them learn about behavioral consequences. If parents, teachers, community members, and other adults are supportive and provide the proper guidance and discipline, adolescents will know that people who care about them will help them develop good decision-making skills (Steinberg & Sheffield, 2001).

Adolescents Develop Socially and Emotionally

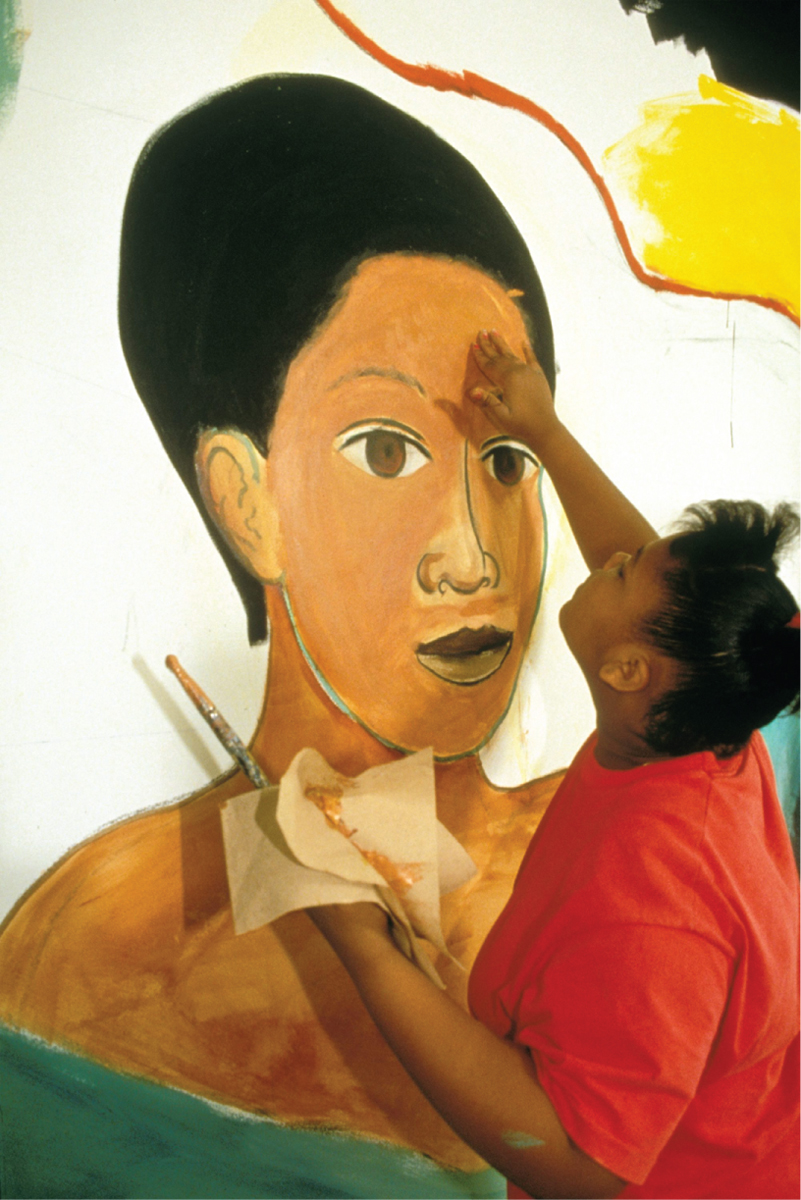

FIGURE 4.26

Development of Identity in a Teen

Who are you? What do you love? How do you see yourself? All adolescents face such questions as part of their socio-emotional development.

Adolescents may be physically able to reproduce, but they are still developing socially and emotionally. Typically, they are focused less on family at this age and more on themselves as they develop friendships and try to answer the question “Who am I?” The search for who each of us is as a person is at the core of socio-emotional development for every adolescent (Figure 4.26).

How we define ourselves is influenced by many factors, including the culture in which we are raised, our gender, and our beliefs about personal characteristics such as race, sex, and age. The quest for identity is an important challenge during development, especially in Western cultures, where individuality is valued. As adolescents seek to understand how they fit into the world and to imagine what kind of person they will become later in life, they build on the preceding developmental stages.

DEVELOPING A UNIQUE IDENTITY The psychologist Erik Erikson proposed a theory of human development based on the psychological challenges we face at different ages in our lives and how these challenges affect our social relationships. Erikson thought of psychosocial development as having eight stages, starting from an infant’s first year of life to old age (Table 4.1). Because it recognizes the importance of the entire life span, Erikson’s theory has been extremely influential in developmental psychology. However, a theory is only as good as the evidence that supports it, and few researchers have tested Erikson’s theory directly.

TABLE 4.1

Erikson’s Eight Stages of Psychosocial Development

STAGE |

AGE |

MAJOR PSYCHOSOCIAL CRISIS |

SUCCESSFUL RESOLUTION OF CRISIS |

1. Infancy |

0–2 |

Trust versus mistrust |

Children learn that the world is safe and |

2. Toddler |

2–3 |

Autonomy versus shame and |

Encouraged to explore the environment, |

3. Preschool |

4–6 |

Initiative versus guilt |

Children develop a sense of purpose by |

4. Childhood |

7–12 |

Industry versus inferiority |

By working successfully with others and |

5. Adolescence |

13–19 |

Identity versus role confusion |

By exploring different social roles, |

6. Young adulthood |

20s |

Intimacy versus isolation |

Young adults gain the ability to commit |

7. Middle adulthood |

30s to 50s |

Generativity versus stagnation |

Adults gain a sense that they are leaving |

8. Old age |

60s and beyond |

Integrity versus despair |

Older adults feel a sense of |

SOURCE: Erikson (1959).

Erikson thought of each life stage as having a major developmental “crisis”—a challenge to be confronted. All of these crises are present throughout life, but each takes on special importance at a particular stage. Although each crisis provides an opportunity for psychological development, a lack of progress may impair further psychosocial development (Erikson, 1980). However, if the crisis is successfully resolved, the challenge provides skills and attitudes that the individual will need to face the next challenge. Successful resolution of the early challenges depends on the supportive nature of the child’s environment as well as the child’s active search for information about what he is skilled at. According to Erikson’s theory, adolescents face perhaps the most fundamental challenge: how to develop an adult identity. This crisis of identity versus role confusion includes addressing questions about who we are. These questions concern our ethnic and cultural identity, how we relate to family and friends, and other individual characteristics.

ETHNIC IDENTITY Culture shapes much of who we are as we develop a full sense of identity during adolescence. Culture also determines whether each person’s identity will be accepted or rejected. In a multiracial country such as the United States, questions of racial or ethnic identity can be complicated. Forming an ethnic identity can be a particular challenge for adolescents of color.

Children entering middle childhood have some awareness of their ethnic identities. That is, they know the labels and attributes that the dominant culture applies to their ethnic group. During middle childhood and adolescence, children in ethnic minority groups often engage in additional processes aimed at ethnic identity formation (Phinney, 1990). The factors that influence these processes vary widely among individuals and groups.

For instance, a child of Mexican immigrants may struggle to live successfully in both a traditional Mexican household and a Westernized American neighborhood and school. The child may have to serve as a “cultural broker” for his family, perhaps translating materials sent home from school, calling government agencies or insurance companies, and handling more adultlike responsibilities than other children the same age. In helping the family adjust to the stress of life as immigrants in a foreign country, the child may feel additional pressures, but he may also develop important skills in communication, negotiation, and caregiving (Cooper, Denner, & Lopez, 1999). And by successfully negotiating these tasks, a child can develop a bicultural identity. That is, the child strongly identifies with two cultures and seamlessly combines a sense of identity with both groups (Vargas-Reighley, 2005). A child in this situation who develops a bicultural identity is likely to be happier, better adjusted, and have fewer problems in adult social and economic roles.

PARENTS AND PEERS If you were asked for one adjective that best describes “teenager,” what would you say? The odds are high that it would be rebellious. Recall from the opening story that even 19-year-old Brooke Greenberg, who was frozen in the body of a 19-month-old toddler, displayed this rebellious nature by refusing to do things she did not like. Throughout the world, it seems that as adolescents develop their own identities, they come into more conflict with their parents.

For most families, this conflict leads only to minor annoyances. It can actually help adolescents develop important skills, including negotiation, critical thinking, communication, and empathy (Holmbeck, 1996). According to Erikson’s theory, negotiating a pathway to a stable identity requires breaking away from childhood beliefs by questioning and challenging parental and societal ideas (Erikson, 1968). But even though adolescents and their parents may disagree and sometimes argue, across cultures parents have a great deal of direct influence on their children’s individual behaviors, values, and sense of autonomy (Feldman & Rosenthal, 1991). Parents also indirectly affect social development by influencing children’s choices about friends (Brown, Mounts, Lamborn, & Steinberg, 1993; Cairns & Cairns, 1994).

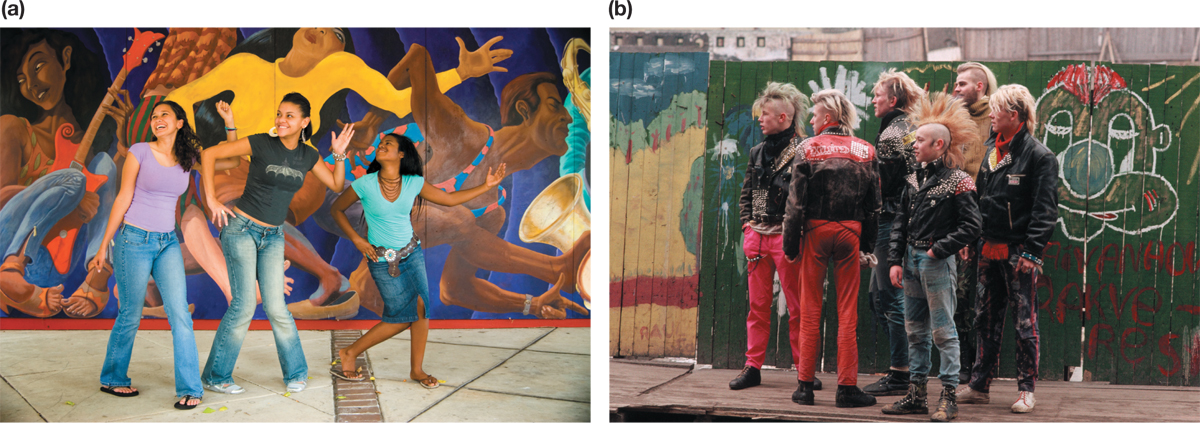

Peers play a crucial role in identity development. Peer groups are created when teenagers form friendships with others who have similar values and worldviews (Figure 4.27a). Observers outside the peer groups tend to place teenagers who dress or act a certain way into groupings, called cliques (Figure 4.27b). The observers often see members of cliques as virtually interchangeable, and community members may respond to all youths from that group in similar ways (Urberg, Degirmencioglue, Tolson, & Halliday-Scher, 1995). The teenagers, however, often see themselves as unique and individual, or as connected to a small subset of close friends, not just as members of a certain clique. The friendships created in these peer groups provide an important sense of belonging, social support, and acceptance.

FIGURE 4.27

Peers and Cliques

(a) Adolescents develop strong friendships with peers who share similar interests and values. (b) Outside observers might tend to place the young men in this peer group into a single clique, “punks,” and would tend to react to all of them in similar ways. Each adolescent, however, might view himself as an individual.

Adolescents Develop Cognitively

Teenagers may be rebellious, but they still need to make good decisions based on the rules of the culture they live in. Moral choices, large ones and small ones alike, affect other people. Ideally, the ability to consider questions about morality develops during childhood and continues into adulthood.

MORAL REASONING AND MORAL EMOTIONS Moral development is the way people learn to decide between behaviors with competing social outcomes. In other words, when is it acceptable to take an action that may harm others or that may break implicit or explicit social contracts? Theorists typically divide morality into moral reasoning, which depends on cognitive processes, and moral emotions. Moral emotions, such as embarrassment and shame, are considered self-conscious emotions. They are called self-conscious because they involve how people think about themselves. For example, the emotional experience of sadness might become the self-conscious emotional experience of shame when it is yourself you feel sad about. It is important to note, however, that moral reasoning is affected by moral emotions (Moll & de Oliveira-Souza, 2007). The development of moral emotions is vital to acting morally.

Psychologists who study the cognitive processes of moral behavior have focused largely on Lawrence Kohlberg’s stage theory. Kohlberg (1984) tested moral-reasoning skills by asking people to respond to hypothetical situations in which someone was faced with a moral dilemma. For example, should a person steal a drug to save his dying wife because he could not afford the drug? Kohlberg was most concerned with the reasons people provided for their answers, not just the answers themselves. He devised a theory of moral judgment that involved three main levels of moral reasoning.

At the preconventional level, people solve the moral dilemma in terms of self-interest. For example, a person at this level might say, “He should steal the drug because he could get away with it.” Or “He should not steal the drug because he will be punished.” At the conventional level, people’s responses conform to rules of law and order or focus on others’ approval or disapproval. For example, a person at this level might say, “He should take the drug because everyone will think he is a bad person if he lets his wife die.” Or “He should not take the drug because that’s against the law.” At the postconventional level, the highest level of moral reasoning, people’s responses center on complex reasoning. This reasoning concerns abstract principles that transcend laws and social expectations. For example, a person at this level might say, “He should steal the drug. Sometimes people have to break the law if the law is unjust.” Or “He should not steal the drug. If people always did what they wanted, it would be anarchy. Society would break down.” Thus Kohlberg believed advanced moral reasoning to include considering the greater good for all people and giving less thought to personal wishes or fear of punishment. You can learn more about Kohlberg’s stages of moral reasoning in the Learning Tip on p. 144.

LEARNING TIP: Applying Kohlberg’s Three Levels of Moral Development

LEARNING TIP: Applying Kohlberg’s Three Levels of Moral Development

This Learning Tip will help you understand Kohlberg’s three levels of moral reasoning by applying them to a situation you may be familiar with: adhering to the speed limit (or not!). Remember: Kohlberg’s levels are not based on whether a person chooses to do or not do something. They are based on the reasoning behind the person’s decision.

STAGE AND AGE OF |

MORAL REASONING |

EXAMPLE OF A PERSON |

|

Preconventional level: often seen in young children, but can be seen in other people too. |

Reasoning about a moral dilemma is based on self-interest, such as getting personal gains, making a good deal, and/or avoiding personal losses. |

“I’m driving the speed limit because my parents said that if I don’t get any speeding tickets for a year they will buy me a car for college.” |

“I have to drive faster than the speed limit. My boss will dock my pay if I’m late for work!” |

||

Conventional level: often seen in older children, most adolescents, and some adults. |

Reasoning about a moral dilemma is based on expectations, such as conforming to social norms to get approval from others and/or obeying legal rules. |

“Everyone is going faster than the speed limit on this highway! I am just keeping up with the speed of the other drivers.” “I’m driving only 20 mph because we are in a school zone. That’s the legal speed limit for driving near schools!” |

|

Postconventional level: seen in only a small proportion of adolescents and adults. |

Reasoning about a moral dilemma is based on “higher” principles, including people’s individual rights in a society and/or abstract ideas about justice and equality. |

“My wife was about to give birth. She was screaming, and I was afraid for her life and the life of our baby. I was driving too fast because surely people’s lives are more important than laws about the speed limit!” |

“It’s unjust that some groups of people are targeted for getting speeding fines more than other groups, so I am not going to obey the speed limit.” |

SOURCE: Kohlberg, 1984.

Not all psychologists agree with moral-reasoning theories such as Kohlberg’s. Critics fault these theories for emphasizing only the cognitive aspects of morality and neglecting emotional issues that influence moral judgments, such as shame, pride, or embarrassment. They believe that moral actions, such as helping others in need, are influenced more by emotions than by cognitive processes.

Finally, not everyone progresses through the stages of moral development at the same rate or in the same order. How can a parent, guardian, or other authority figure help guide a younger person’s moral development? According to the research, there is great value in showing the general consequence of a specific behavior. Saying “You made Chris cry. It’s not nice to hit, because it hurts people” is more effective than saying simply “Don’t hit people.” Such explanation promotes children’s sympathetic attitudes, appropriate feelings of guilt, and awareness of other people’s feelings. The resulting attitudes, feelings, and awareness then influence the children’s moral reasoning and behavioral choices, which also help instill moral values that guide behavior throughout life. This cycle of moral development can be readily seen in cases of bullying, as described in Using Psychology in Your Life.

USING PSYCHOLOGY IN YOUR LIFE:

Bullying

Have you ever been the victim of bullying? Have you seen children or adolescents being bullied? Have you ever bullied someone? Bullying is when someone repeatedly uses physical power or control over another person, behaving aggressively in a way that is unwanted (Espelage and Holt, 2012). There are many types of bullying:

• Physical: physical contact that hurts a person—for example, hitting, kicking, punching, taking away an item and destroying it—and physical intimidation, such as threatening someone and frightening him enough to make him do what the bully wants.

• Verbal: name-calling, making offensive remarks, or joking about a person’s appearance, religion, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation; and verbal intimidation.

• Social: spreading rumors or stories about someone, excluding someone from a group on purpose, or making fun of someone by pointing out her differences.

• Cyber: sending aggressive, threatening, and/or intimidating messages, pictures, or information using social media, computers (e-mail and instant messages), or cell phones (text messaging and voicemail).

Bullying is a complex behavior with many contributing factors. However, experts tend to agree that bullies might not strongly feel the moral emotions of guilt and shame (Hymel, Rocke-Henderson, & Bonanno, 2005). Bullies also often show increased moral disengagement, such as indifference or pride, when explaining their behavior and more-positive attitudes about using bullying to respond to difficult social situations. Because bullying tends to get people what they want and society traditionally turns a blind eye to it, bullying goes on. However, both kids who are bullied and those who bully others can have serious, lasting problems.

So what can you do? Here are three steps adults should take when they see an act of bullying occurring among children and adolescents:

1. Stop the bullying on the spot: Intervene in a calm and respectful manner, separate the children, make sure they are safe, and get any needed medical help.

2. Find out what happened: Once you have separated the kids, get all of their views on what happened. Seek evidence from other people who witnessed the act. Do not jump to conclusions or place blame.

3. Support the kids involved: Listen to the person being bullied, assure him that it’s not his fault, and work to resolve the bullying situation. Also work with the person doing the bullying to help him realize his behavior is wrong, understand why he bullies, and take steps to reduce the behavior.

By modeling good moral reasoning and good moral behavior, and reducing the rewards associated with bullying, you can help children and adolescents develop appropriate moral values. Even other kids can learn to be more than bystanders and help reduce bullying. For more information on how to respond to bullying and prevent it, visit www.stopbullying.gov.

|

|

■ During puberty, both males and females undergo physical changes, including development of secondary and primary sex characteristics and changes in the brain.

■ Adolescence is the time when teens develop socio-emotionally by trying to resolve the psychosocial conflict of identity versus role confusion.

■ The establishment of gender identity reflects the interaction of nature (biological factors of sex and hormones) and nurture (gender socialization).

■ During adolescence, cognitive development leads to more-sophisticated moral reasoning.

LEARNING GOALS

LEARNING GOALS READING ACTIVITIES

READING ACTIVITIES

4.3 CHECKPOINT:

4.3 CHECKPOINT: