5.1 How Do Sensation and Perception Affect Us?

|

|

a. Remember the key terms about sensation and perception. |

List all of the boldface words and write down their definitions. |

b. Apply the four steps from sensation to perception to your life. |

Using a sensory input you have experienced, describe the four steps from sensation to perception. |

c. Understand absolute threshold and difference threshold. |

Use your own words to compare absolute threshold and difference threshold. |

d. Apply signal detection theory to real life. |

Use signal detection theory to explain the four ways new parents could respond to their baby’s crying. |

Imagine you take half a grapefruit out of the refrigerator and dig into it with a spoon. Some juice splashes out of the fruit and hits your nose and mouth. What do your senses tell you? You smell some strong fragrance. You feel something cold on your skin. You taste something sharp on your tongue. So far, your experience consists of raw sensation. Your sensory systems have detected features of the juice.

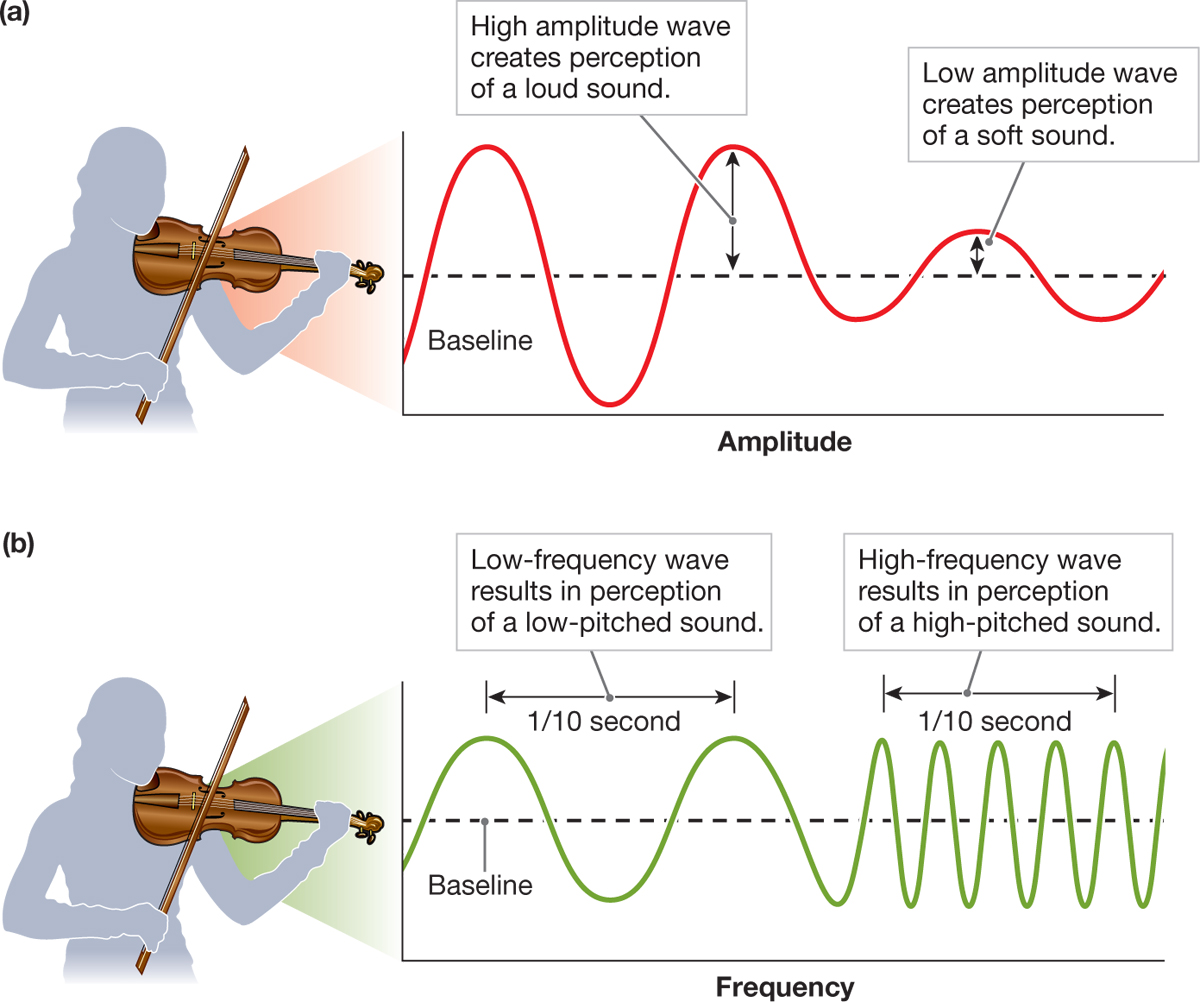

Sensation is the detection of physical stimuli from the world around us and the sending of that information to the brain. Physical stimuli can be light waves, sound waves, food molecules, odor molecules, temperature changes, or pressure changes on the skin. In sensing the splash of the grapefruit juice, you are sensing food molecules, odor molecules, slight temperature changes, and slight pressure changes.

Perception is the brain’s further processing of sensory information. This processing results in our conscious experience of the world. The essence of perception is interpreting sensation. That is, our perceptual systems (as opposed to our sensory systems) translate sensation into information that is meaningful and useful. In the above example, perception is interpretation of the sensory stimuli of cold droplets, a strong smell, and a sharp taste as qualities of grapefruit.

But even when people experience the exact same sensory input (sensation), they experience that input differently (perception). If you like grapefruit, you might experience this splash as at least partly pleasant. If you dislike grapefruit—suppose your father has insisted that you eat it—you might experience the splash as totally unpleasant. The Try It Yourself exercise on p. 158 will help you begin to understand the differences between sensation and perception.

TRY IT YOURSELF: Sensation and Perception

TRY IT YOURSELF: Sensation and Perception

If you and your friends look at the same car, will you all agree on the color? Check it out with this example:

1. Look only at the picture of the car. Decide what color the car is. Then look at the color bar and decide which color sample is most similar to how you see the color of the car. Write down both of your answers.

2. Now ask a few other people to do the things in step 1.

3. Most likely, some people have labeled the car color the same way you did. Some people have chosen different labels. However, the label a person chooses for the color doesn’t tell us what that person has actually perceived.

4. But even people who labeled the car the same way you did might have chosen a different color sample from the one that you chose. This result suggests you had different perceptions of the same color.

What does this demonstration show? The sensory input, the sensation, is the same for people. Yet each person has a unique perception of that input. Taken together, sensation and perception make up all of our individual experiences with the world.

Our Senses Detect Physical Stimuli, and Our Brains Process Perception

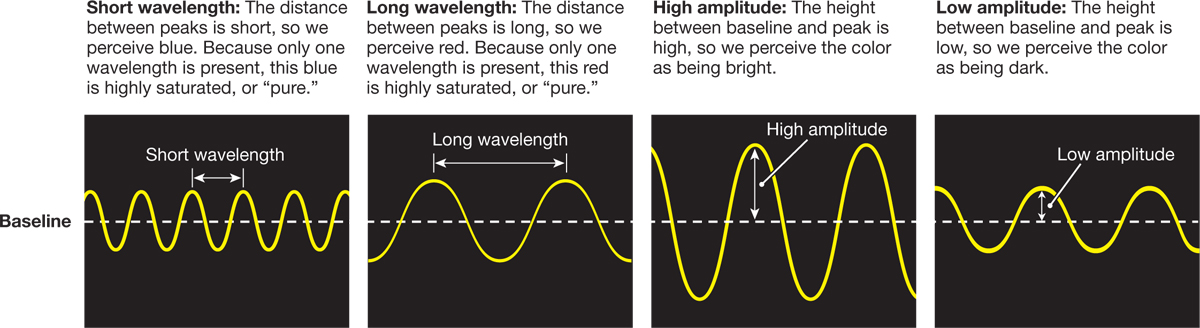

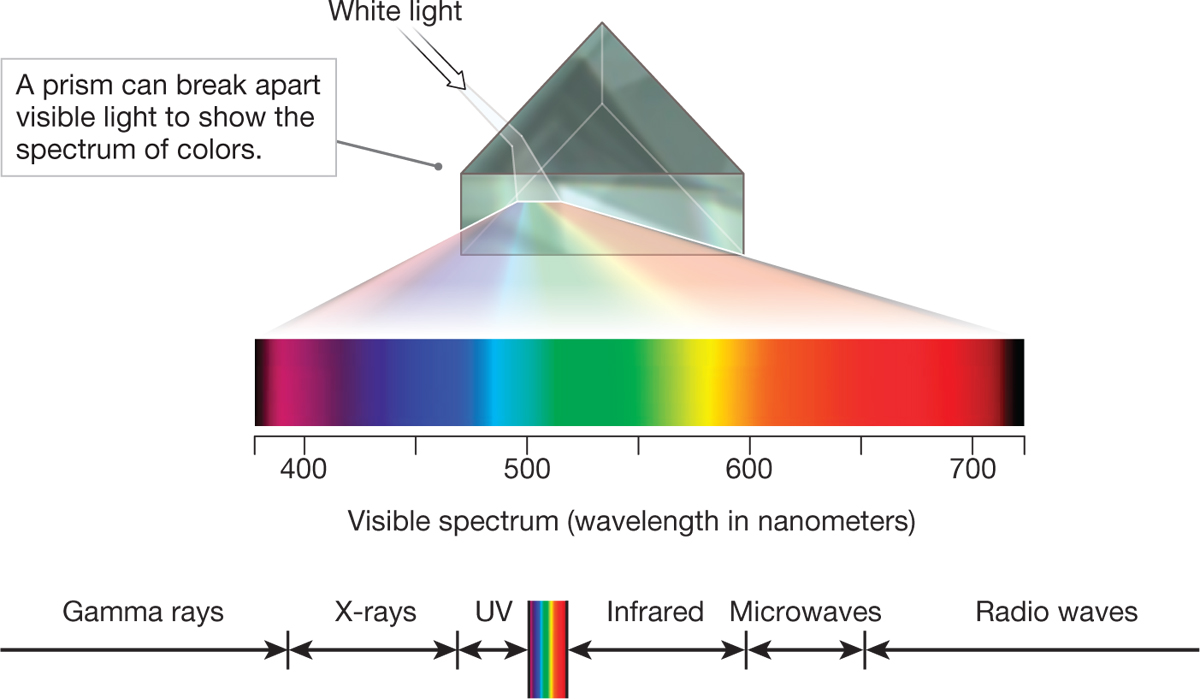

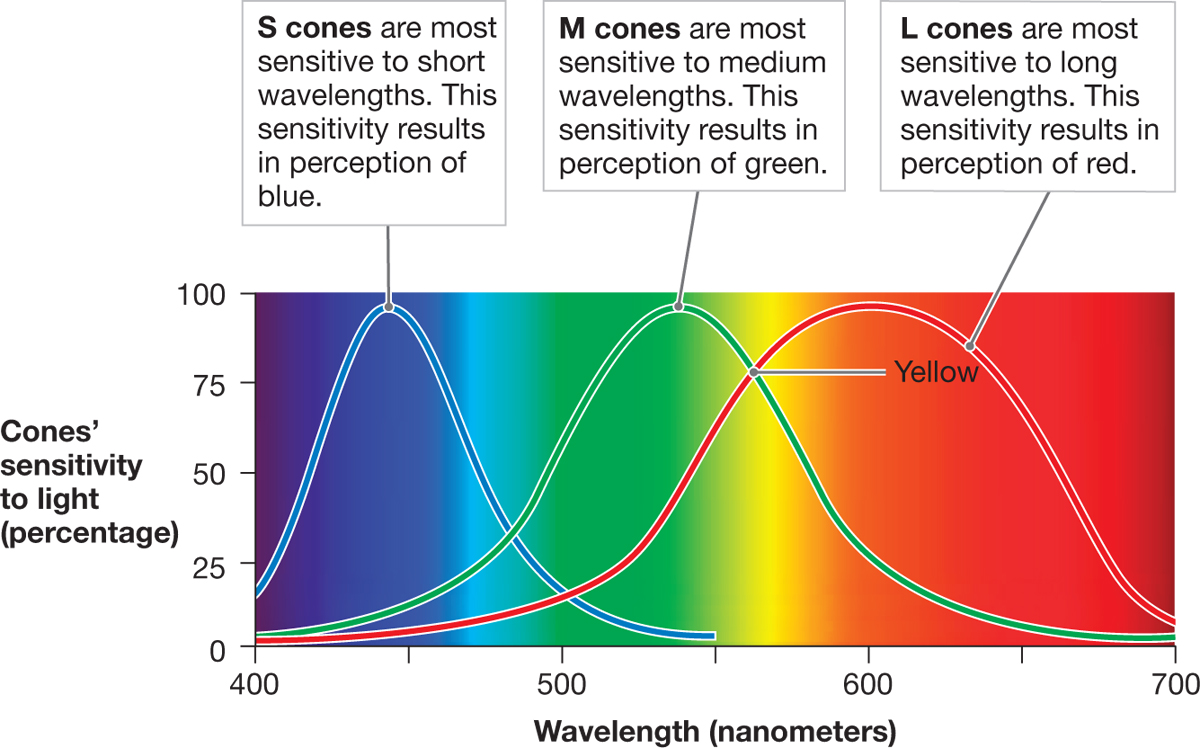

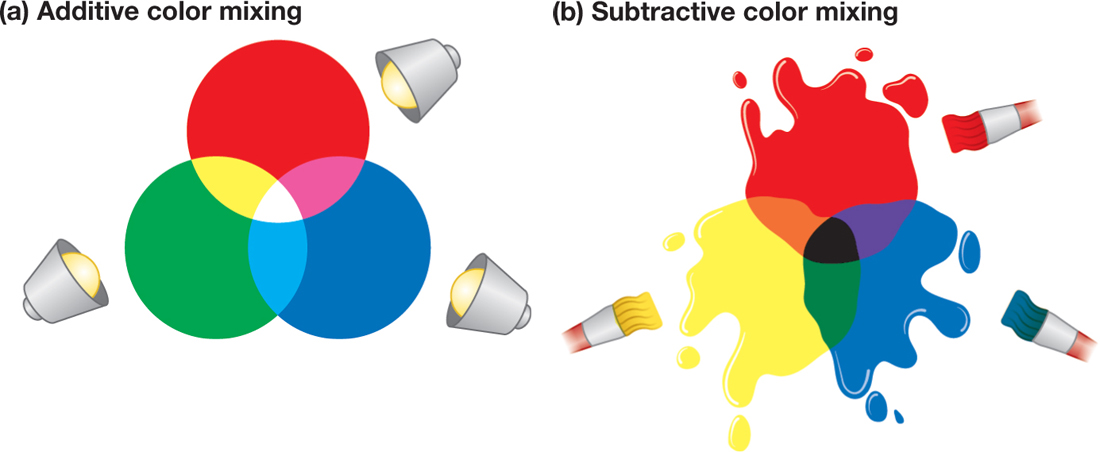

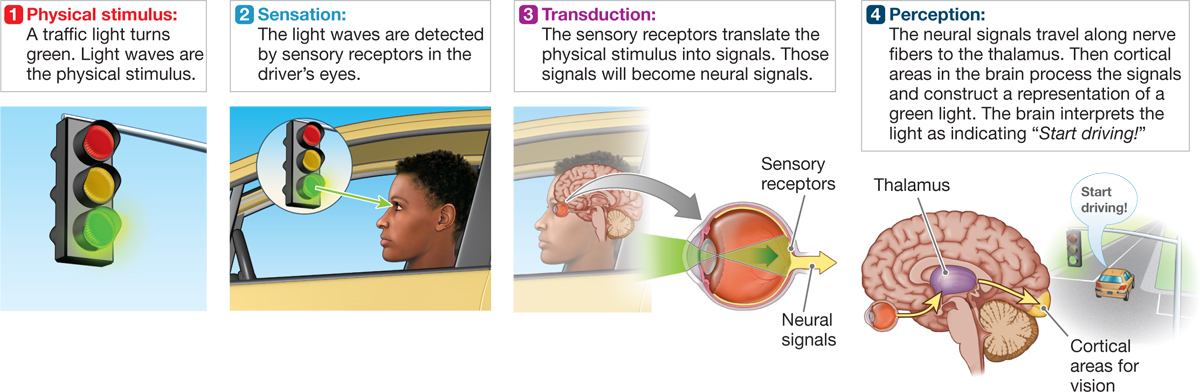

Suppose you are driving, and the traffic signal changes from red to green. Believe it or not, there is actually no red or green color in the signal or in the light you see. Instead, your eyes and brain enable you to see the redness or greenness of the light. Objects in the physical world don’t actually have color. Each object reflects light waves of particular lengths. Our visual systems interpret those waves as different colors.

So how do light waves get changed into information that the brain can process? Special cells in our eyes respond to these different wavelengths and change that physical signal into information that the brain can interpret. If you are driving and your brain receives information about a green traffic light, your brain most likely will interpret that light as meaning “Go.”

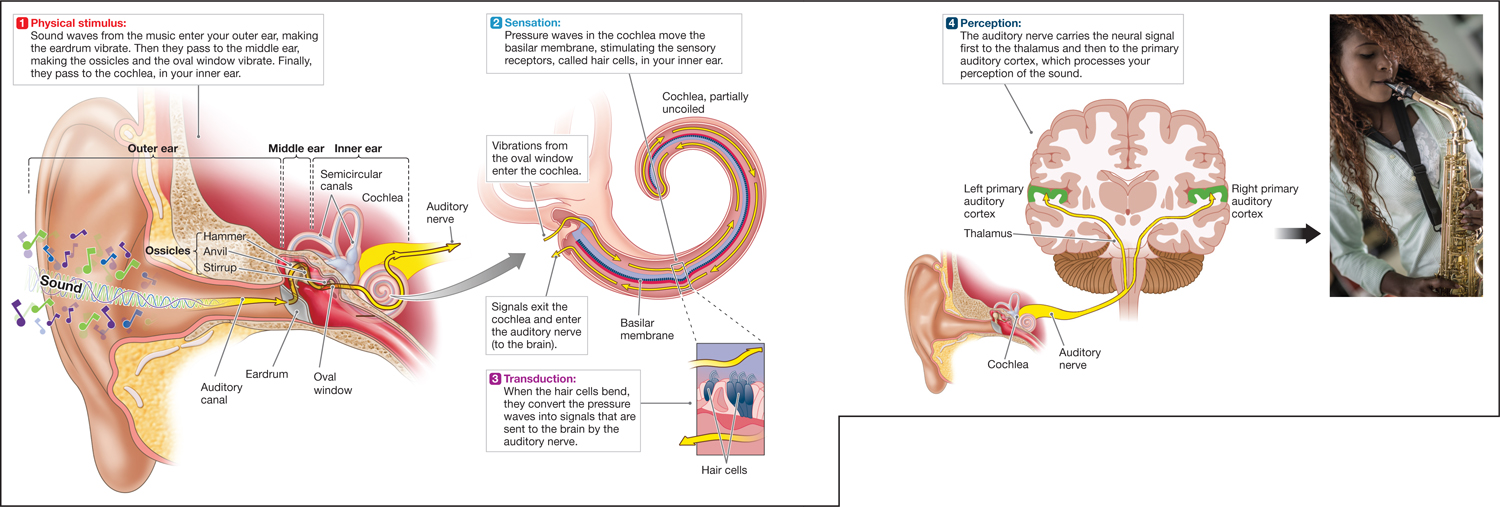

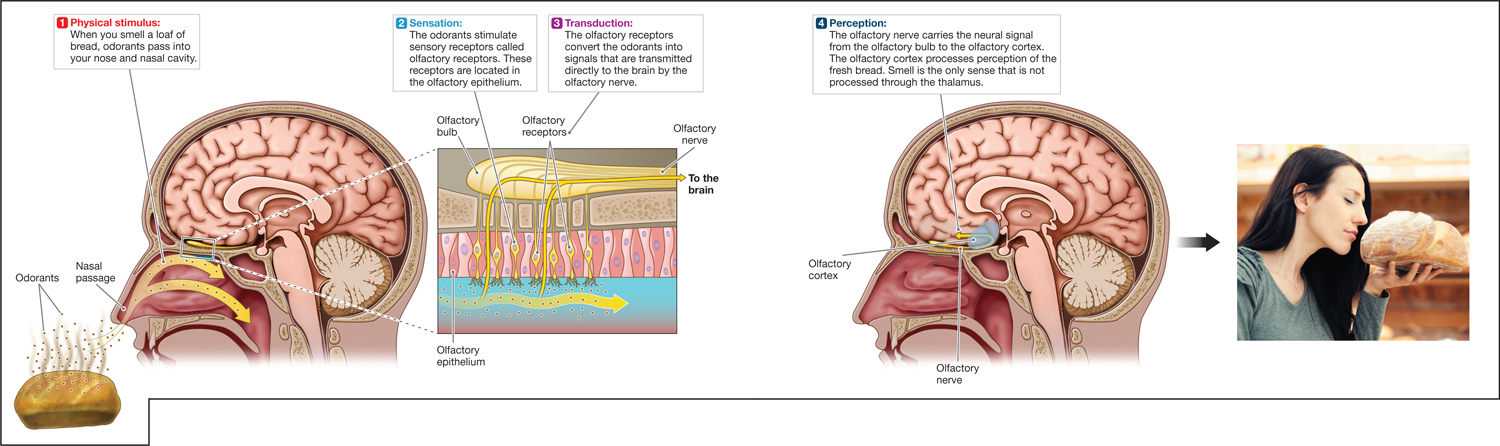

FROM SENSATION TO PERCEPTION To understand more clearly both sensation and perception, imagine that you drive up to a traffic signal as it turns green. The green light is actually the physical stimulus in the form of light waves (Figure 5.2, Step 1). That stimulus is detected by specialized cells called sensory receptors. The receptors’ detection of the stimulus is sensation (see Figure 5.2, Step 2).

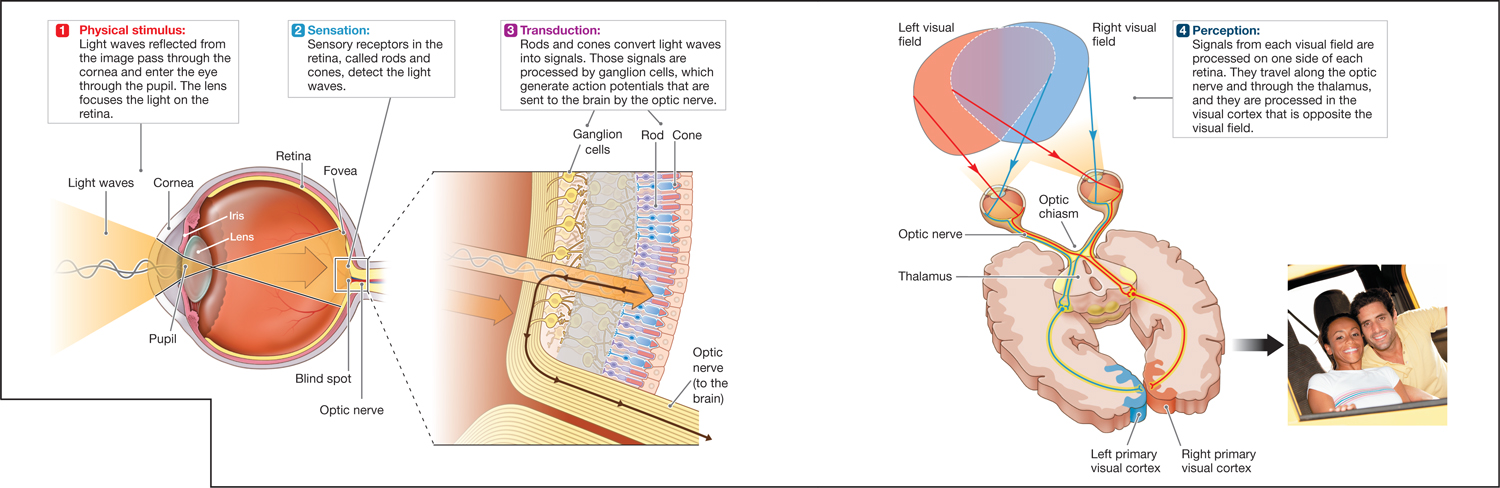

FIGURE 5.2

From Sensation to Perception

Here is a summary of the four steps in the process of changing sensory input into a personal experience. The example is for sensation and perception of vision, but the steps in general also apply to hearing, taste, smell, and touch. However, information about smell is not processed through the thalamus.

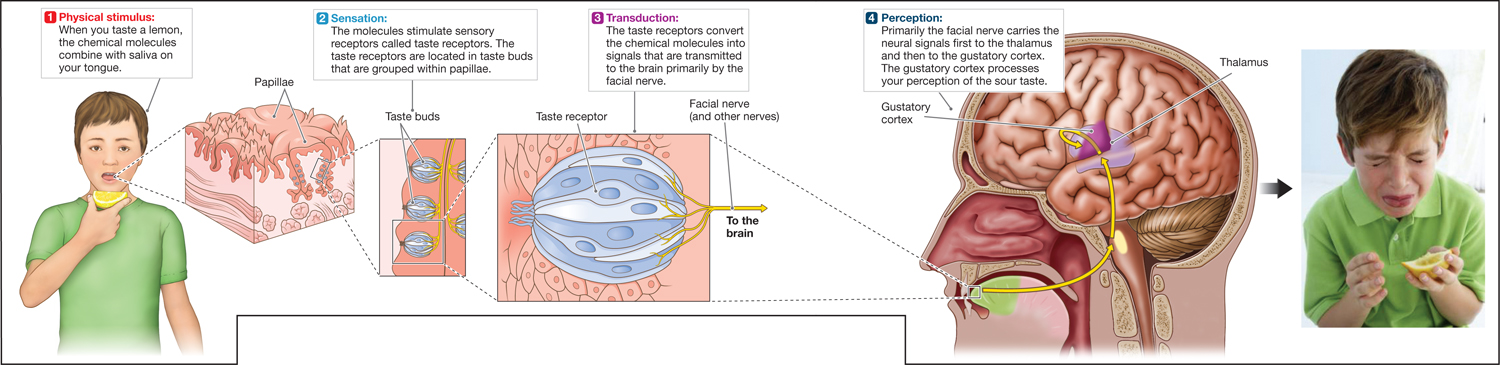

In a process called transduction, the sensory receptors change the stimulus input to signals that the brain can understand (see Figure 5.2, Step 3). In some cases, such as taste, transduction directly results in neurons’ firing action potentials (to review the firing of action potentials, see Chapter 2). For vision, more processing must happen before the information is coded as action potentials. When the brain does process the action potentials, you will interpret them as green light. You will also register the meaning of that traffic signal as “Go.” This further processing of the information following transduction is perception (see Figure 5.2, Step 4).

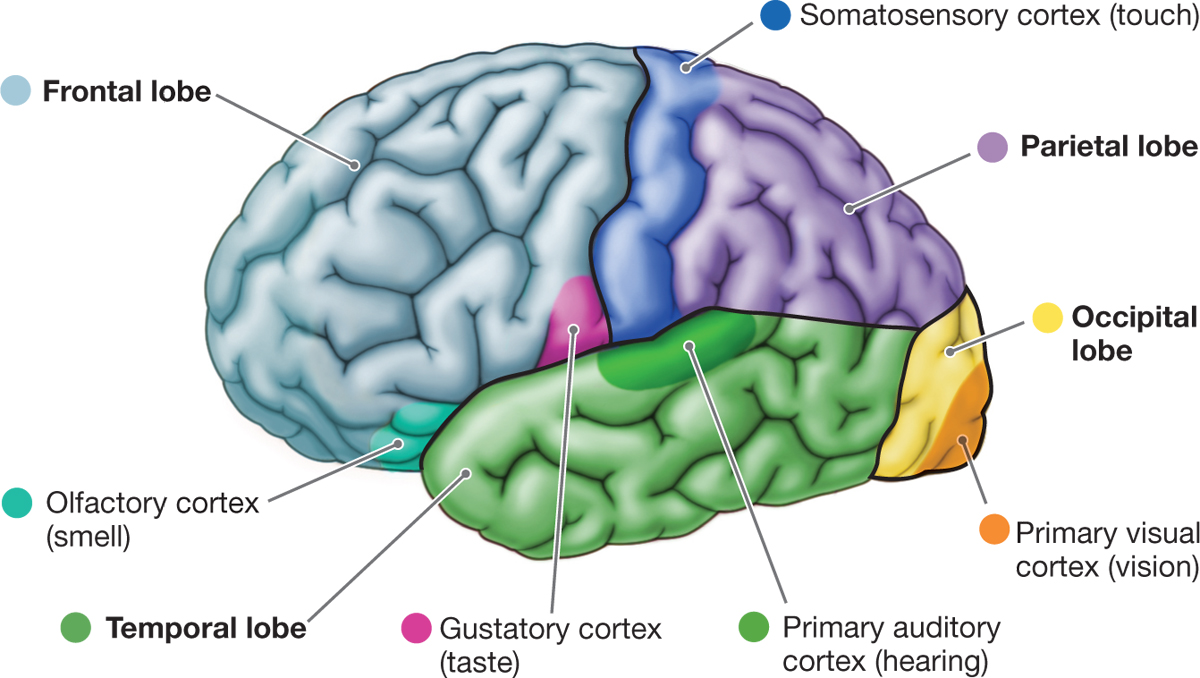

This example demonstrates the general processes of sensation and perception. However, the details are slightly different for each sense. In this chapter, you will learn about the four steps of sensation and perception for each major sensory system. In each case, a physical stimulus is detected, specialized sensory receptors transduce the stimulus information, and neurons fire action potentials. These action potentials are the sensory information that is sent to specific regions of the brain for interpretation (Figure 5.3).

FIGURE 5.3

The Brain’s Primary Sensory Areas

Except for smell, all sensory input is first processed through the thalamus. Then inputs are sent to cortical regions that process information about vision, hearing, taste, smell, and touch.

The sum of this activity, across all of your senses, is your huge range of perceptions. And your perceptions add up to your experience of the world. If you get splashed with grapefruit juice or see the color of a traffic light, your sensations and perceptions enable you to interpret the information and respond appropriately. For example, you decide the juice is delicious or you accelerate the car.

There Must Be a Certain Amount of a Stimulus for Us to Detect It

Stop reading for a moment and listen. What do you hear? Perhaps voices in the next room or music down the hall. But can you hear the buzzing of the fly that you see on the window across the room? How much physical stimulus is required for our sense organs to detect sensory information? How much change in the physical stimulus is required before we notice that change in the sensory information?

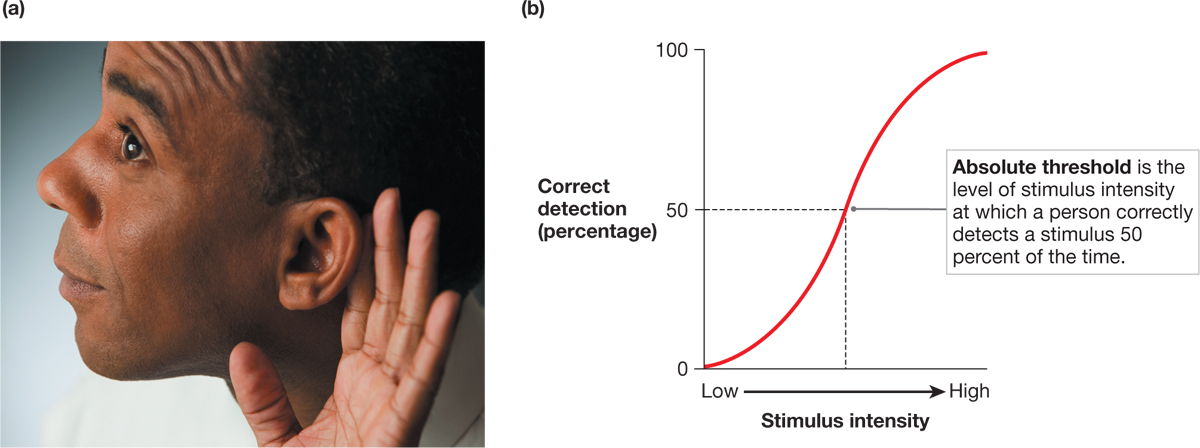

THRESHOLD TO DETECT SENSORY INFORMATION An enormous amount of physical stimulation from the world around you reaches your sensory receptors. Even so, you do not notice much of it. Physical stimulation has to go beyond some level before you experience a sensation. The absolute threshold is the minimum amount of physical stimuli required before you detect the sensory input (Figure 5.4). You can also think of the absolute threshold as the smallest amount of a stimulus a person can detect half of the time the stimulus is present. For instance, how loudly must someone in the next room whisper for you to hear it? In this case, the absolute threshold is the quietest whisper you could hear half the time. Table 5.1 lists some approximate minimum levels of physical stimuli that are required to detect sensory input for each sense.

FIGURE 5.4

Absolute Threshold

(a) Can this man detect a soft sound, such as a whisper? (b) This graph shows the relationship between the intensity of stimulus input and a person’s ability to correctly detect the input. The absolute threshold is the point of stimulus intensity that a person can correctly detect half the time.

TABLE 5.1

Absolute Threshold to Detect Input for Each Sense

SENSE |

MINIMUM SENSORY INPUT REQUIRED FOR DETECTION |

Taste |

1 teaspoon of sugar in 2 gallons of water |

Smell |

1 drop of perfume diffused into the entire volume of six rooms |

Touch |

A fly’s wing falling on your cheek from a distance of 0.04 inch |

Hearing |

The tick of a clock at 20 feet under quiet conditions |

Vision |

A candle flame 30 miles away on a dark, clear night |

SOURCE: Galanter (1962).

A difference threshold is the smallest difference that you can notice between two pieces of sensory input. In other words, it is the minimum amount of change in the physical stimulus required to detect a difference between one sensory experience and another. Suppose your friend is watching a television show. You are reading and not paying attention to what’s on the screen. If a commercial comes on that is louder than the show, you might look up, noticing that something has changed. In this case, the difference threshold is the minimum change in volume required for you to detect a difference.

The difference threshold increases as the stimulus becomes more intense. Say you pick up a 1-ounce jar of spice and a 2-ounce jar of spice. You will easily detect the difference of 1 ounce. Now pick up a 5-pound package of flour and a package that weighs 5 pounds and 1 ounce. The same difference of 1 ounce between these two will be harder to detect, maybe even impossible to detect.

The principle at work here is called Weber’s law. This law is based on the work of the nineteenth-century psychologist Ernst Weber. The law states that the just-noticeable difference between two sensory inputs is based on a proportion of the original sensory input rather than on a fixed amount of difference. What does that mean? Assume the overall stimulus input is less intense (as in the case of the 1-ounce container). A specific change in input (say 1 ounce) can easily be detected by a person. But now assume the original stimulus is more intense (as in the case of the 5-pound package). That same change in input (1 ounce) is much harder to detect. Weber’s law may sound complex. But as shown in Has It Happened to You?, we experience difference thresholds all the time.

HAS IT HAPPENED TO YOU?

Difference Threshold

Have you ever been in a car and had to keep turning up the music so that you could hear it above the wind or road noise? You may have turned it up a bit but heard no difference in loudness. So you turned it up a bit more. And maybe even louder still, until you could finally hear the music. This example illustrates the difference threshold. You could not detect small changes in loudness because the music was already so loud. But later on, when you entered the car under quieter conditions, you were probably shocked at how loud the music really was.

SIGNAL DETECTION THEORY The concept of an absolute threshold means that either you saw something or you did not. Your detection depended on whether the intensity of the sensory input was above or below the threshold. But can your judgment also affect your ability to detect sensory input? Signal detection theory accounts for human judgment in sensation. This theory states that detecting a sensory input, called the signal, requires making a judgment, called the response, about the presence or absence of the signal, based on uncertain information (Green & Swets, 1966).

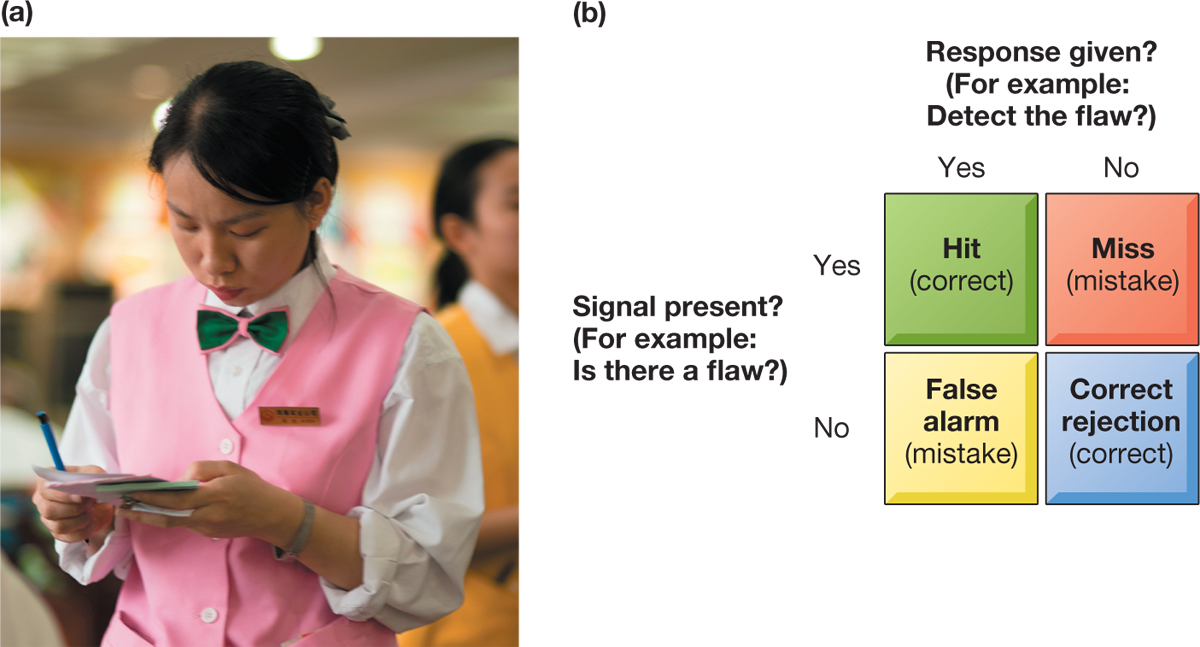

To understand this theory, think about the many jobs where people have to decide if items are imperfect. In restaurants, servers check the food before it goes out to the customers. In retail stores, employees check products before they go on display. Signal detection theory explains how situations like these can have one of four outcomes (Figure 5.5). If a signal is present—such as a flaw in a food order—and the person responds to it, the outcome is called a hit. If the person does not respond to the signal, the outcome is a miss. By contrast, if there is no signal but the person responds anyway, the outcome is a false alarm. If there is no signal and the person does not respond, the outcome is a correct rejection.

FIGURE 5.5

Signal Detection Theory

(a) Have you ever had a job where you had to look for flaws in food orders or products? (b) According to signal detection theory, there are four possible outcomes when a person is asked to detect the presence of a sensory input, such as a flaw. These outcomes depend on whether an input is present. They also depend on the person’s ability to judge the presence of an input. This theory accounts for people’s biases in making judgments about whether a stimulus is present.

The person’s sensitivity to the signal is usually computed by comparing the hit rate with the false alarm rate. This comparison corrects for any bias the participant might bring to the situation. Signal detection theory also explains how a worker can be biased in situations like these. Imagine that a server gets paid extra money every time he notices that an order has a flaw, such as the wrong vegetable, and asks the cook to correct that flaw before the order goes to the table. Or imagine that a retail worker receives a bonus every time she detects damaged goods and removes them from the shelves. This financial incentive will result in workers being biased toward responding when they see flaws. This bias will result in more hits but also more false alarms. By contrast, imagine the worker has to pay a financial penalty every time he wrongly delays a food order or she wrongly removes a retail product. The worker will have the opposite bias: toward not responding to a flaw. This bias will result in more misses but also more correct rejections.

Signal detection theory helps us understand how a person can be biased toward responding, or not responding, even given the same amount of sensory input. As you can imagine, all sorts of factors influence the decision to respond to a particular sensory input. Consider, for example, the person’s experience, motivation, attention, training, and knowledge of the consequences of whatever response is made.

SENSORY ADAPTATION Our sensory systems are tuned to notice changes in our surroundings. It is important for us to be able to notice such changes because they might require responses. It is less important to keep responding to unchanging stimuli. Sensory adaptation is a decrease in sensitivity to a constant level of stimulation.

For example, imagine that you are studying and work begins at a nearby construction site. When the equipment starts up, the sound seems particularly loud and annoying. After a few minutes, the noise seems to have faded into the background. If a stimulus is presented continuously, the responses of the sensory systems that detect it tend to diminish over time. Similarly, when a continuous stimulus stops, the sensory systems usually respond strongly as well. If the construction noise suddenly halted, you would likely notice the silence.

|

|

■ Sensation is the detection of light, sound, touch, taste, and smell. Perception is how the brain interprets this information.

■ Sensory receptors transduce sensory input into signals. Except for smell, this information is sent to the thalamus and relevant parts of the cortex for further processing.

■ Absolute threshold and difference threshold describe how much physical stimulus must be present for detection to happen.

■ Signal detection theory explains how our judgments affect our ability to detect input.

■ Our senses adapt to constant stimulation and detect changes in our environment.

LEARNING GOALS

LEARNING GOALS READING ACTIVITIES

READING ACTIVITIES

5.1 CHECKPOINT:

5.1 CHECKPOINT: