LEARNING GOAL

Summarize the six strategies for learning how to learn.

LEARNING GOAL

Summarize the six strategies for learning how to learn.

Have you ever read a textbook chapter and then realized you had no idea what it said? Have you ever done poorly on a test and then realized you had not really learned the material? Have you ever pulled an all-nighter to cram for an exam and then flunked it? If you have ever experienced situations in which your personal thoughts on how best to study have failed you, then you are not alone.

Fortunately, you can benefit from research on the science of learning in psychology and other fields, such as education. That is, you can use psychological principles to improve your study habits, your learning, and your academic performance (American Psychological Association, 2020a). The Learning to Learn figure on page 7 summarizes six important learning strategies that will have a major IMPACT—Improving, Monitoring, Practicing, Attending, Connecting, and Thinking Deeply—on your ability to succeed in this or any other course. You will learn more about these strategies in other Learning to Learn figures throughout this book, and you will practice them when you see IMPACT Learning Pauses in the margins.

IMPACT LEARNING PAUSE

Are You Practicing?

Practicing the right way improves learning. Follow these suggestions to use repeated practice in every chapter.

Improving When you have a growth mindset, you recognize that your intelligence and skills are not fixed. Instead, you believe that you can increase your knowledge and skills even in areas that are challenging for you. The key to a growth mindset is believing that you have a choice about what you think and how you act. That is, you can improve your learning and performance when you make an effort to work hard, use good study strategies, and get helpful feedback from others. Research reveals the educational benefits of a growth mindset, which include persisting even after a failure and increasing academic achievement (Dweck, 2019). Students who have underachieved in school or whose families do not have a high level of income may benefit even more than others from adopting a growth mindset (Sisk et al., 2018; Yeager et al., 2016). In addition, adopting a growth mindset helps both low- and high-performing students seek out educational experiences that are more challenging (Paunesku et al., 2015). In other words, you can start improving now by choosing to have a growth mindset.

A text at the top reads: “Psychological research reveals six strategies that help you improve your study skills, learn more, and succeed in school. Throughout this book, Learning to Learn figures further explain each strategy, and Learning Pause activities provide opportunities to practice each strategy. Start using psychology to learn psychology - or anything else”. The first strategy is “Improving”, and depicts an illustration of a woman sitting at a desk and holding up a sheet of paper. A trash can is beside her, filled with crumpled papers. The text beside reads: “When you adopt a growth mindset, you believe you can do the hard work to change how you think, feel, and act to improve in the areas you have identified”. The second strategy is “Monitoring”, and depicts an illustration of a woman looking at a board containing a checklist. The text beside reads: “Self-regulated learning helps you set goals, plan your studying, use good study strategies, and check your progress”. The third strategy is “Practicing”, and depicts an illustration of a man sitting at a desk, with a laptop open and a candle placed on a book. A cyclic flow chart is depicted above him. The text beside reads: “By actively answering questions across several study sessions, you use repeated practice, which will improve your quiz and test performance”. The fourth strategy is “Attending”, and depicts an illustration of a person wearing headphones, looking into a laptop. A mobile device is placed away from him on another table, with a “no” sign on it. The text beside reads: “By focusing your selective attention on what you need to study and by ignoring distractions, you will remember better”. The fifth strategy is “Connecting”, and depicts an illustration of a woman thinking of an idea. A board beside her has a flowchart on it. The text beside reads: “You can use cues to help you remember when you connect new information with your own knowledge, skills, and experiences”. The sixth strategy is “Thinking Deeply”, and depicts an illustration of a woman sitting at a desk in such a way that her chair is tilted slightly back and her feet are on the desk. She is thinking about D N A structure, a newborn bay, and an adult man. The text beside reads: “When you use elaboration, you use an active process of explaining ideas and giving examples in order to learn better”. The first letters of each strategies are underlined, forming the word Impact.

Monitoring Imagine you are going on vacation and you get in the car and drive. You do not think of your destination or how you will get there, and you do not check that you are on the right route. Will this approach get you to where you want to go? It certainly will not. This example reveals the importance of monitoring your goals and the methods you use to achieve them. Monitoring is one of many skills that are a part of self-regulated learning (Usher & Schunk, 2018; Winne, 2018). When you engage in monitoring, you set measurable learning goals, make specific study plans (including managing how much time you need to study), use effective strategies to reach your goals, check your learning several times along the way to ensure you are on track, and make changes as needed. Research has suggested that self-monitoring may help you reach your academic goals (Ghanizadeh, 2017).

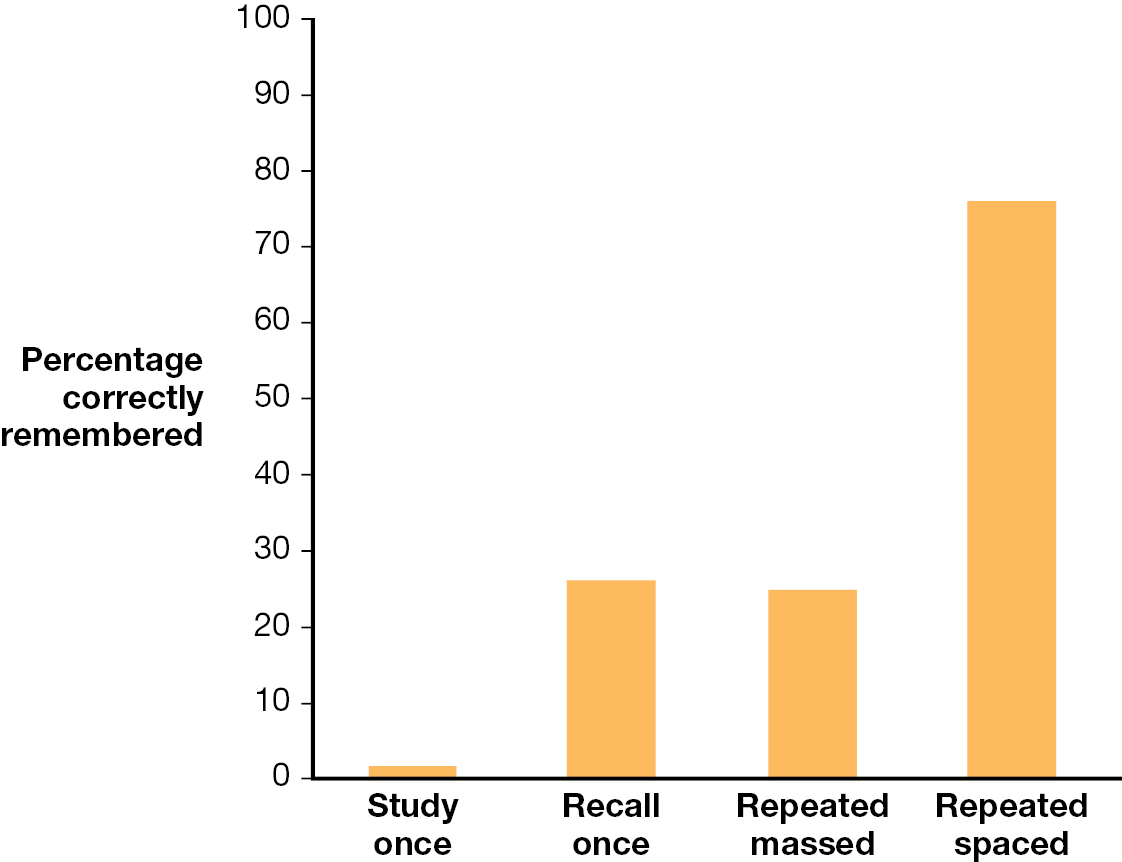

The vertical axis is labeled Percentage correctly remembered, and ranges from 0 to 100 in increments of 10. The data from the graph is as follows: Study once, 2 percent; Recall once, 27 percent; Repeated massed, 26 percent; Repeated spaced, 76 percent. All values are approximate.

FIGURE 1.2 Practicing Can Improve Learning

Students studied vocabulary words by (1) reading a word definition (Study Once), (2) typing the definition (Recall Once), (3) typing the definition three times in a row (Repeated Massed), and (4) typing the definition three times spaced across a study session (Repeated Spaced). A week later, students remembered more words if they had practiced with them three times spaced across the session.

Practicing “Practice makes perfect.” This common phrase suggests that all practice is equal, but it is not. For example, contrary to what you may believe, rereading is not an effective strategy to practice with material you are trying to learn (Dunlosky et al., 2013; Miyatsu et al., 2018). Instead, practicing is effective only if it forces you to actively think to remember the material you learned (Karpicke, 2017). The very effective method of repeated practice includes answering sample quiz or practice test questions, such as those found in this book in the Learning Goal Checks, figures, and the Practice Test at the end of each chapter (Adesope et al., 2017; Roediger & Karpicke, 2006; Bertilson et al., 2021). It is also related to better academic performance—for example, on tests. (For a review, see McDermott, 2021.) In fact, repeated practice is effective for students regardless of their personal characteristics (Bertilsson et al., 2021) and is related to better academic performance—for example, on tests (for a review, see McDermott, 2021). In addition, as Figure 1.2 shows, practicing a concept is even more effective when you space your practice within one study session (Karpicke & Bauernschmidt, 2011) or across study sessions over days (Wiseheart et al., 2019). Combining these practicing strategies is a powerful study strategy (J. J. Janes et al., 2020).

Attending Like many students, you may believe you can multitask and still study effectively. But if you are focusing on YouTube while you study at home or on your Snapchat streaks while you are in class, then you are not focusing on what you are supposed to be learning. According to the principle of selective attention, you can focus on only so much at one time. You must therefore focus on what is important and ignore what is not important. In fact, research suggests that heavy media multitasking is related to negative effects on attention and memory (Uncapher & Wagner, 2018). Furthermore, studies have found that students who use Facebook, send text messages, and surf the internet during class do more poorly in college courses than students who do not (Gingerich & Lineweaver, 2014; Junco & Cotten, 2012). Even students who are sitting near someone who is surfing the Web during class receive lower grades (Sana et al., 2013). So, to maximize your learning, turn off your electronic devices and stop focusing on what is not important. Instead, start attending to what you need to learn.

Connecting You may now see that learning how to study in the right way can create powerful learning. In fact, when you see a relationship between new information and information you already know, your brain naturally uses that relationship as a connection that helps you remember that new information. Therefore, to learn new material, you should try to create as many connections with it as possible. One way to do so is to relate new ideas to facts and skills you already know (Alexander et al., 1994; Ambrose & Lovett, 2014; Campbell & Campbell, 2008; Wade & Kidd, 2019). For example, you can connect new information you are learning with knowledge and skills you already have, whether that new information is about parenting, playing soccer, fixing cars, traveling, or anything else. These connections provide important cues that help you organize new information when you experience it and access it later on from your memory (Willingham, 2010).

IMPACT LEARNING PAUSE

Are You Thinking Deeply?

Learning Goals in each study unit aid you in thinking deeply about the information. Use these elaboration techniques to truly learn the information.

Thinking Deeply If you think learning is easy, then you are probably not doing it very effectively. Learning the right way is hard work, and some of your strategies may not be very effective. For example, although highlighting material is a very popular study method with students, it is not usually effective because it does not require you to do much thinking about the information (Dunlosky et al., 2013; Miyatsu et al., 2018). By contrast, explaining concepts and giving examples of them from your own life are related to better memory and learning (Dunlosky et al., 2013). These strategies work because every time you learn something, you create “memory traces” in your brain. When you work deeply with the information by explaining it or giving examples, you strengthen the memory traces and you are more likely to remember it later on. You can start using this thinking strategy, called elaboration, immediately to improve your academic success.

LEARNING GOAL CHECK: REVIEW