LEARNING GOAL

Describe diversity and identify three ways that diversity is increasing in psychology.

LEARNING GOAL

Describe diversity and identify three ways that diversity is increasing in psychology.

The topics studied in modern psychology are becoming more varied thanks to research across the interconnected domains of psychology. But not just the areas of inquiry are changing. Today, different types of people with varying life experiences are now more likely to become psychologists. Psychologists are also recruiting a wider array of people to participate in their research to ensure that their conclusions apply as widely as possible. In addition, students who take psychology classes increasingly come from all walks of life.

Diversity Has Many Benefits To understand how psychology and psychologists are changing today, we must understand what diversity is. At its most basic level, diversity refers to those characteristics that make us seem different from one another in a specific context or situation. Diversity among people is extremely complex. It can pertain to characteristics that are visible (skin color) or not (national origin) and to characteristics that are inborn (genetic traits) or changeable (language). Thus, diversity includes all of the many differences we experience in terms of race, ethnicity, biological sex, national origin, culture, language, religion, sexual orientation, gender, age, political affiliations, socioeconomic status, abilities, values, characteristics, preferences, and more.

Demographic trends reveal that modern societies have become increasingly diverse (Ramos et al., 2016). And research suggests that increasing diversity also brings social and educational benefits for students (Smith & Schonfeld, 2000), improves some types of group problem solving (Hong & Page, 2004), and aids society at large by helping people adapt, increase their flexibility, and become more creative (Jones et al., 2014). Because of the importance of diversity, you will encounter this theme repeatedly in the textbook with respect to the psychologists discussed, the research described, the study participants recruited, the examples given, and the images displayed.

Psychologists Today Are More Diverse Looking back at Figure 1.7, what do the three people in the photo, who are credited with the birth of experimental psychology, have in common? You may be thinking that they all appear to be White men. The photo reflects the dominant thinking at the start of the twentieth century that only White men had the ability to succeed in higher education and that it was socially unacceptable for other people to pursue advanced degrees. For this reason, the early history of psychology was not characterized by much diversity. Yet some early psychologists fought to break down these barriers.

For example, Mary Whiton Calkins was one of the first female graduate students in psychology (Figure 1.10a). She attended Harvard University (at that time a men’s college) in 1890, but even though she completed all of the requirements for a doctorate in psychology she was denied the degree because she was a woman. Although Calkins was later offered a doctorate from Radcliffe College, the women’s college associated with Harvard, Calkins turned it down on principle. Nonetheless, in 1905 she became the first woman to be elected president of the American Psychological Association. In addition, her research on memory has been very influential.

FIGURE 1.10Psychologists Who Paved the Way for Diversity in the Field

(a) In 1890, Mary Whiton Calkins was one of the first female graduate students in psychology, but she was denied the doctoral degree she had earned because she was a woman. Her influential research into memory helped her become the first woman to be elected president of the American Psychological Association. (b) In 1920, Francis Cecil Sumner became the first Black person in the United States to earn a doctorate in psychology. He founded the department of psychology at Howard University.

In 1920, Francis Cecil Sumner (Figure 1.10b) became the first Black person in the United States to be awarded a doctoral degree in psychology. In fact, Sumner was one of only 11 Black people to earn a doctorate in any field between 1876 and 1920, compared to the 10,000 White recipients of doctoral degrees (Guthrie, 1998). Throughout his career, Sumner encountered difficulties from both White colleagues and Black people as he tried to walk the fine line of advancing the status of Black people in the United States (Black et al., 2004). Eventually, Sumner went on to found the Department of Psychology at Howard University.

Today, psychologists are becoming much more diverse (American Psychological Association, 2020b) with data from 2019 showing that 70 percent of psychologists in the workforce identify as women. Since 2004, the percentage of psychologists from underrepresented groups has increased from 10 percent to 16 percent. In 2019, 7 percent of psychologists identified as Hispanic, 4 percent as Asian, 3 percent as Black, and 2 percent as a person of color from another group. Although this is good news, we need more information about the many ways in which psychologists vary beyond race and ethnic affiliation—for example, in terms of biological sex, gender identity, country of origin, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, differences in abilities, and more.

Although psychologists are becoming more diverse, the discipline must continue to cultivate diversity in professional psychologists (Figure 1.11). One way to encourage people from diverse backgrounds to become psychologists is to have a wide array of professional organizations to support them, such as the Association of Black Psychologists (https://www.abpsi.org/), the National LatinX Psychological Foundation (https://www.nlpa.ws/), the Asian American Psychological Association (https://aapaonline.org/), the American Arab, Middle Eastern, and North African Psychological Association (https://www.amenapsy.org/), and the American Indian and Alaska Native Society of Indian Psychologists (https://www.nativepsychs.org/).

The headshots, from left to right, are as follows: Row 1: Germine H. Awad - prejudice, racism, and discrimination; Serena Chen - self and identity, self-compassion, social power and inequality; Stephen L. Chew - student learning, memory, cognitive basis of effective teaching; Lisa M. Diamond - development and expression of gender and sexuality across the life span. Row 2: Angela Duckworth - self-control, behavior change, grit; Milton A. Fuentes - Latinx, multicultural, and family psychology; motivational enhancement; Ebony Glover - biological or social basis of fear, anxiety, mental health; Patrick R. Grzanka - intersectionality, sexualities and gender, reproductive justice. Row 3: Jacqueline S. Gray - mental health among American Indians; Lasana T. Harris - social, legal and economic decision-making, moral judgments, emotional processing; Neil A. Lewis, Junior - identity, motivation, social disparities; Michelle Nario-Redmond - disability identity, ableism, and reducing prejudice. Row 4: Viji Sathy - broadening participation in STEM, quantitative psych and assessment, inclusive teaching; Danielle A. Sheypuk - disability, dating, and sexuality; Sanjay Srivastava - interpersonal perception, personality dynamics and development, psychology of online societies; Simine Vazire - psychological research methods and practices, how research is evaluated.

FIGURE 1.11 Psychology Is a Field Where You Can Belong

Psychologists today identify in ways that make them, and their work within the field, unique. The people shown here reflect just a tiny amount of the diversity in the field of psychology, which has a responsibility to make psychology a career that is available to all who want to pursue it. For more information, see the American Psychological Association’s Diversity Initiative at https://www.apa.org/pubs/authors/diversityinitiative.

In short, there are many benefits of having greater diversity among psychologists, especially given that people’s own experiences can be the spark that lights a fire to investigate specific psychological phenomena. You will read about the contributions of many psychologists from diverse backgrounds and identities throughout every chapter of this book.

Psychology Research Must Include Diverse Participants If psychologists themselves are becoming more diverse, what about the people who participate in their research? An important study found that 96 percent of the participants in psychology research lived in Western, industrialized countries such as the United States, even though just 12 percent of the world’s population lives in these countries (Arnett, 2008). In addition, 80 percent of the participants in the studies were students in undergraduate psychology courses. But are the mental processes, behaviors, and brain activity of these participants similar to those of people from more diverse backgrounds? To answer this question, some psychologists today explore whether or not psychological processes are similar across diverse groups of people.

Let’s consider what happens when psychologists begin to include more diverse people as participants in their research. Consider this question: How do you respond when you are faced with a really stressful event, such as having to quarantine or wear a face mask during a pandemic? Early research on the topic of stress revealed that animals, including humans, show a fight-or-flight response, in which they either lash out at what is causing them stress or run from it (Cannon, 1932). However, prior to 1995 only 17 percent of participants in stress response research were female, so these results were based mainly on the reactions of male participants (Taylor et al., 2000). When research began to include more female participants, researchers found that females were more likely to respond to stress with a tend-and-befriend response, in which they care for others and develop social networks to provide support (Taylor et al., 2000). For people, the results suggest that some psychological processes can vary based on gender. Because this research used a more diverse group of participants, we now know more about how people of different genders in general tend to respond to stress.

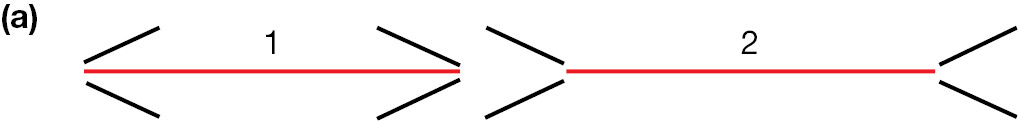

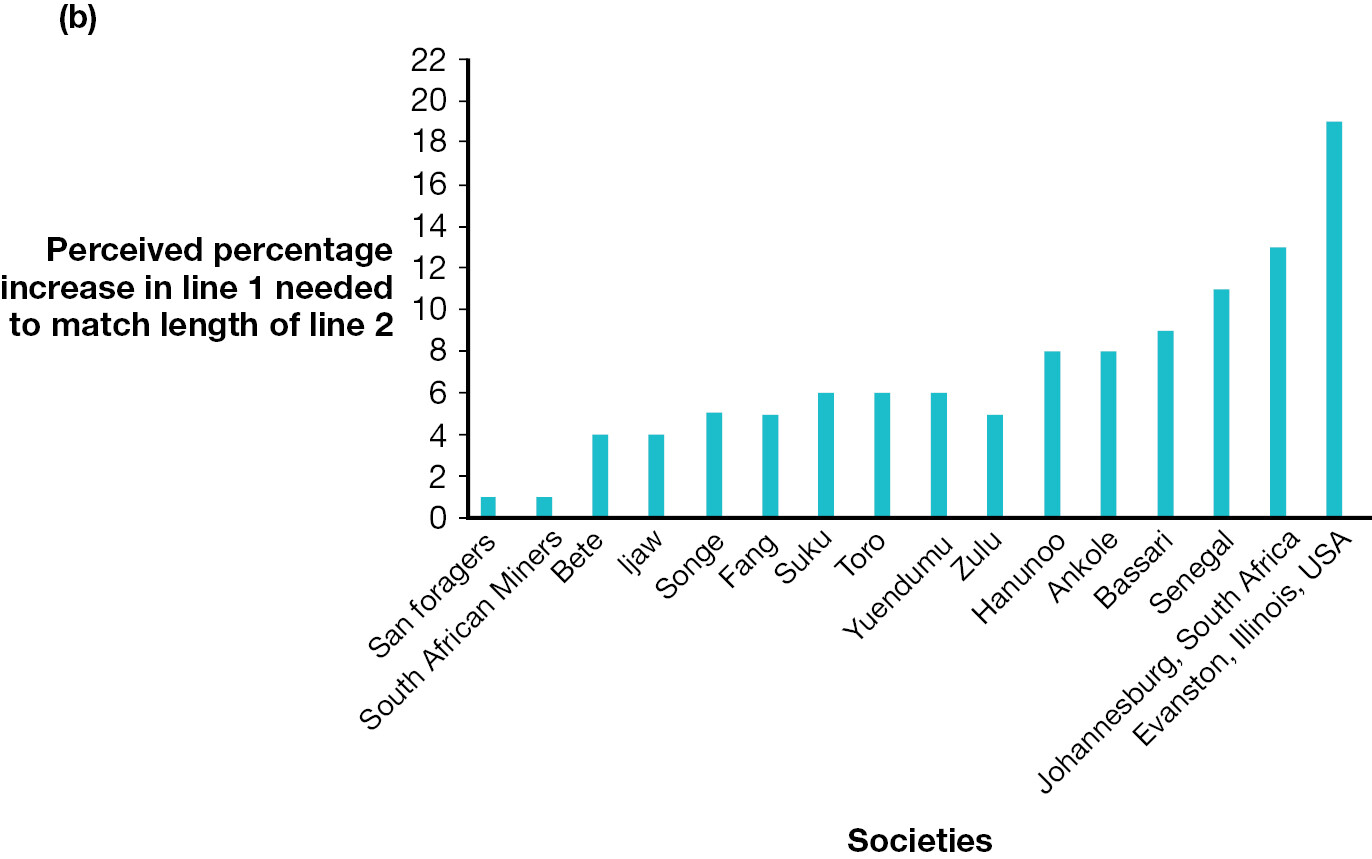

As another example, look at Figure 1.12a on page 22, which is called the Müller-Lyer illusion. Are lines 1 and 2 the same length or different lengths? If you are like the participants in a research study that took place in Evanston, Illinois, in the United States, then you probably think that line 2 is longer. But, as Figure 1.12b shows, research participants from small societies of people who forage, hunt, and farm for a living, such as the San foragers of the Kalahari, perceive the two lines as almost the exact same length (Segall et al., 1966). In fact, the two lines are exactly equal in length. Yet Americans fall prey to this illusion while people from small-scale societies tend not to see the illusion. These results suggest that the culture of research participants can affect their psychological processes. In this case, the researchers suggested that exposure to the straight lines and 90-degree angles that are commonly seen in modern societies may influence how visual perception develops, resulting in the illusion that line 2 is longer.

The diagram shows two identical lines, labeled 1 and 2. At the left end point of line 1, two small lines diverge to the right with equal slopes, one upward, and one downward. At the right end point of line 1, two small lines diverge to the left with equal slopes, one upward, and one downward. At the left end point of line 2, two small lines diverge to the left with equal slopes, one upward, and one downward. At the right end point of line 2, two small lines diverge to the right with equal slopes, one upward, and one downward. This forms an illusion, making line 2 appear longer than line 1.

The bar graph shows Perceived percentage increase in line 1 needed to match length of line 2 along the vertical axis, ranging from 0 to 22 in increments of 2. The heights of the bars are as follows: San foragers, 1; South African miners, 1; Bete, 4.2; Ijaw, 4.2; Songe, 5.4; Fang, 5; Suku, 6.2; Toro, 6.2; Yuendumu, 6.2; Zulu, 5; Hanunoo, 8; Ankole, 8; Bassari, 8.8; Senegal, 11; Johannesburg, South Africa, 12.2; Evanston, Illinois, U S A, 20. All values are approximate.

FIGURE 1.12People Across Cultures Perceive the Müller-Lyer Illusion Differently

(a) When viewing the Müller-Lyer illusion shown here, participants must judge the lengths of lines 1 and 2. Do you see the two lines as the same length or one line as longer? In fact, the two lines are of equal length. (b) Research shows that participants across cultures do not perceive these lines in the same way. Participants from the United States tend to say that line 1 must be lengthened by about 20 percent to equal the length of line 2. Participants from small-scale societies, such as the San foragers from the Kalahari, tend to say that line 1 does not need to be lengthened hardly at all to equal the length of line 2.

A review of psychological research has identified many differences in psychological processes between educated participants from Western, industrialized, rich, and democratic countries and participants from other cultures (Henrich et al., 2010). Some of the affected processes include many aspects of spatial cognition, visual perception, memory, attention, categorization, and moral reasoning. Moreover, variability in participants’ psychological processes can be predicted based on how “culturally distant” the participants are from the dominant culture in the United States (Muthukrishna et al., 2020). For this reason, to see the greatest range in psychological processes, psychologists should conduct research with participants from diverse backgrounds, as in the example with the Müller-Lyer illusion. This idea is very important because psychologists use empiricism to investigate people’s mental activities, behaviors, and brain processes, with the goal of applying their findings as widely as possible. In every chapter of this textbook you will have the opportunity to learn about the psychological processes of diverse people.

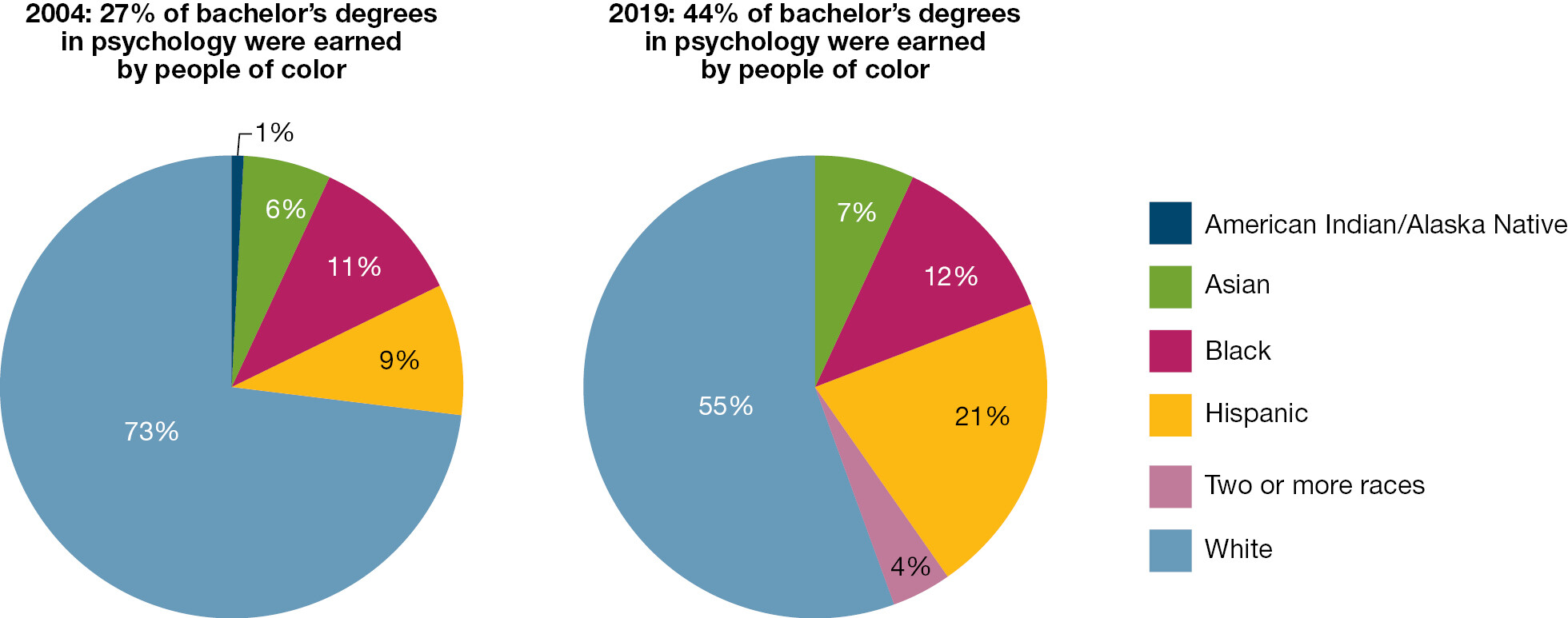

Psychology Students Are Also More Diverse Psychology has come a long way since the turn of the nineteenth century, when Mary Whiton Calkins and Francis Cecil Sumner started to pave the way for people from diverse backgrounds to study psychology. Today, more women students pursue psychology than ever before. In 2019, 79 percent of graduates earning bachelor’s degrees in psychology were women (American Psychological Association, 2020c). In addition, psychology students are increasingly diverse in terms of their race and ethnicity (Figure 1.13). Whereas only 27 percent of students earning a bachelor’s degree in psychology in 2004 were people of color, by 2019 that percentage had risen to 44 percent. Of these psychology graduates in 2019, 21 percent identified as Hispanic, 12 percent as Black, 7 percent as Asian, and 4 percent as multiracial. However, the relative proportion of people of color earning advanced degrees in psychology is lower than it is for bachelor’s degrees, which suggests that the field can do more to support advanced training for a more diverse population of students who want to pursue an advanced degree in psychology.

The first pie chart depicts the People of Color Earning Bachelor’s Degrees in Psychology in 2004. The data are as follows: White, 73 percent; Black, 11 percent; Hispanic, 9 percent; Asian, 6 percent; American Indian or Alaska Native, 1 percent. The second pie chart depicts the People of Color Earning Bachelor’s Degrees in Psychology in 2019. The data are as follows: White, 55 percent; Hispanic, 21 percent; Black, 12 percent; Asian, 7 percent; Two or more races, 4 percent.

FIGURE 1.13 More People of Color Are Earning Bachelor’s Degrees in Psychology

Between 2004 and 2019, the number of people of color who earned bachelor’s degrees in psychology increased by 17 percent. Note that in 2004 no data are shown for people who were two or more races. Also, in 2019 the rates of American Indians/Alaska Natives earning bachelor’s degrees in psychology were not distinguishable from zero, so no data for these groups are shown on the chart.

In short, regardless of who you are in terms of your age, biological sex, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, or other factors, there are more opportunities in psychology today for you, and students like you, than ever before (Figure 1.14).

FIGURE 1.14Psychology Students Are More Diverse Than Ever Before

Regardless of your age or how you think of yourself, there are people like you who are studying psychology at your school, across your country, and in other parts of the world.

LEARNING GOAL CHECK: REVIEW & APPLY