LEARNING GOAL

Summarize the four stages of cognitive development.

LEARNING GOAL

Summarize the four stages of cognitive development.

Two-year-old Rowen is in her car seat looking at a book. She asks her father, who is driving the car, “What’s this?” Her father replies, “Sorry, I am looking at the road. I can’t see what you see there in the backseat.” But Rowen does not understand, so she keeps asking the same question. Young children cannot put themselves in another person’s shoes to understand what that person senses, thinks, or feels. However, through exchanges such as this one, children begin to learn more about the world around them. Like most children, Rowen will eventually realize that other people’s perspectives are different from her own. In other words, she will develop cognitively.

Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development The developmental psychologist Jean Piaget investigated how children’s thinking changes as they develop. By exploring the mental abilities of his own three children and many others, Piaget discovered that children’s minds truly do work in a different way than adults’ minds.

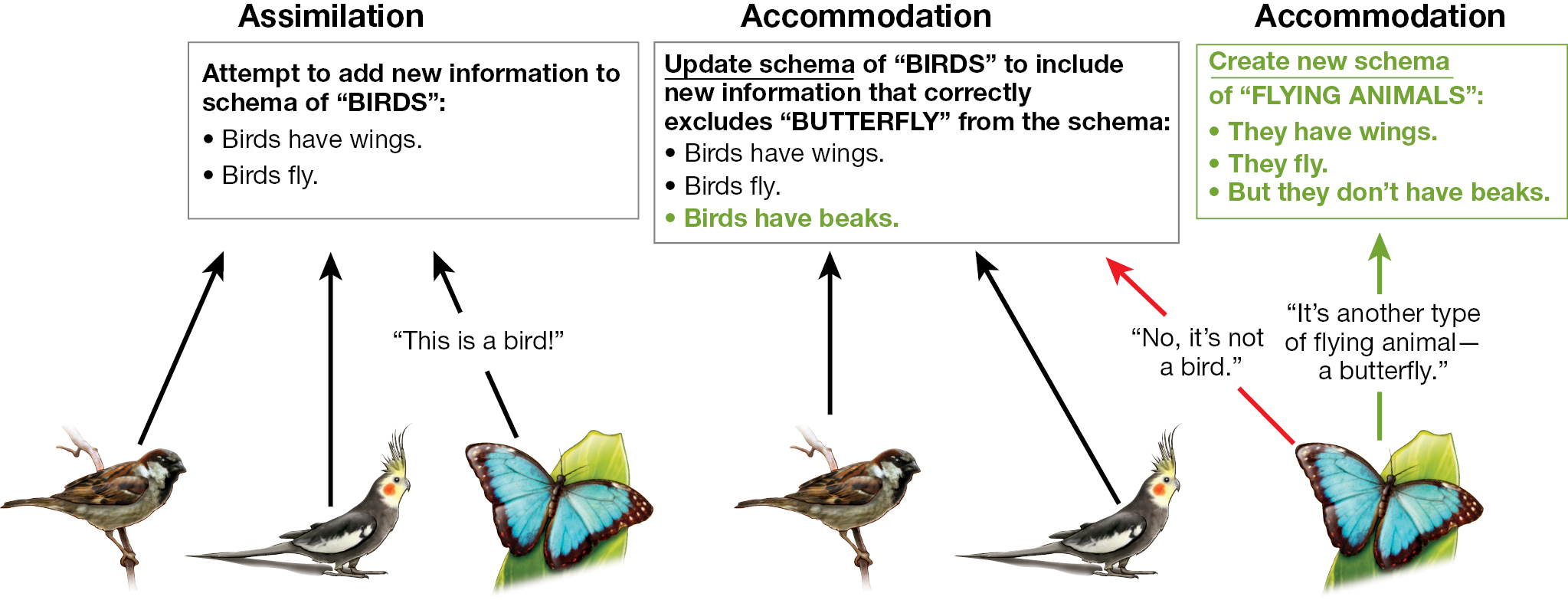

Specifically, Piaget proposed that we change how we think as we form new schemas, or ways of thinking about how the world works. Piaget described two ways that we develop a schema: through accommodation and assimilation, as summarized in the Learning Tip on page 150. During assimilation, we place a new experience into an existing schema. For example, a 2-year-old might see a butterfly for the first time and shout, “Bird!” After all, a butterfly has wings and flies, just as birds do. The child is trying to assimilate the idea of butterfly into the existing schema of birds. But the toddler’s parent says, “No, honey, that’s a butterfly! See, it doesn’t have a beak!”

LEARNING TIP Assimilation and Accommodation

The picture has two sections that are labeled as follows: Assimilation, and Accommodation. Accommodation is further divided into Update schema and creating a new schema. Assimilation: An illustration of a sparrow, parrot, and butterfly is shown. The three illustrations point to a text that reads, Attempt to add new information to the schema of "Birds": Birds have wings, Birds fly. A text about the butterfly reads This is a bird. Accommodation: An illustration of a sparrow, parrot, and butterfly is shown. The three illustrations point to a text that reads, Update schema of "Birds" to include new information that correctly excludes "Butterfly" from the schema: Birds have wings, Birds fly, Birds have beaks. A text above the butterfly reads, No it’s not a bird. Another text reads, Create new schema of “FLYING ANIMALS”: They have wings. They fly. But they don’t have beaks. A text above the butterfly reads “It’s another type of flying animal a butterfly.”

During accommodation, we create a new schema or dramatically alter an existing one to include new information that otherwise would not fit into the existing schema. In our example, the child must now accommodate the new information about beaks into the existing schema about birds. The child must also accommodate by creating a new schema about flying animals that can include “butterfly.” The constant repetition of assimilation and accommodation allows a child to develop increasingly complex schemas over time. These schemas allow the child to think in more sophisticated ways. Piaget’s research became the basis for his influential theory that children go through four progressively complex stages of cognitive development, as summarized in Figure 4.15.

![]() Piagetian Tasks Demonstration

Piagetian Tasks Demonstration

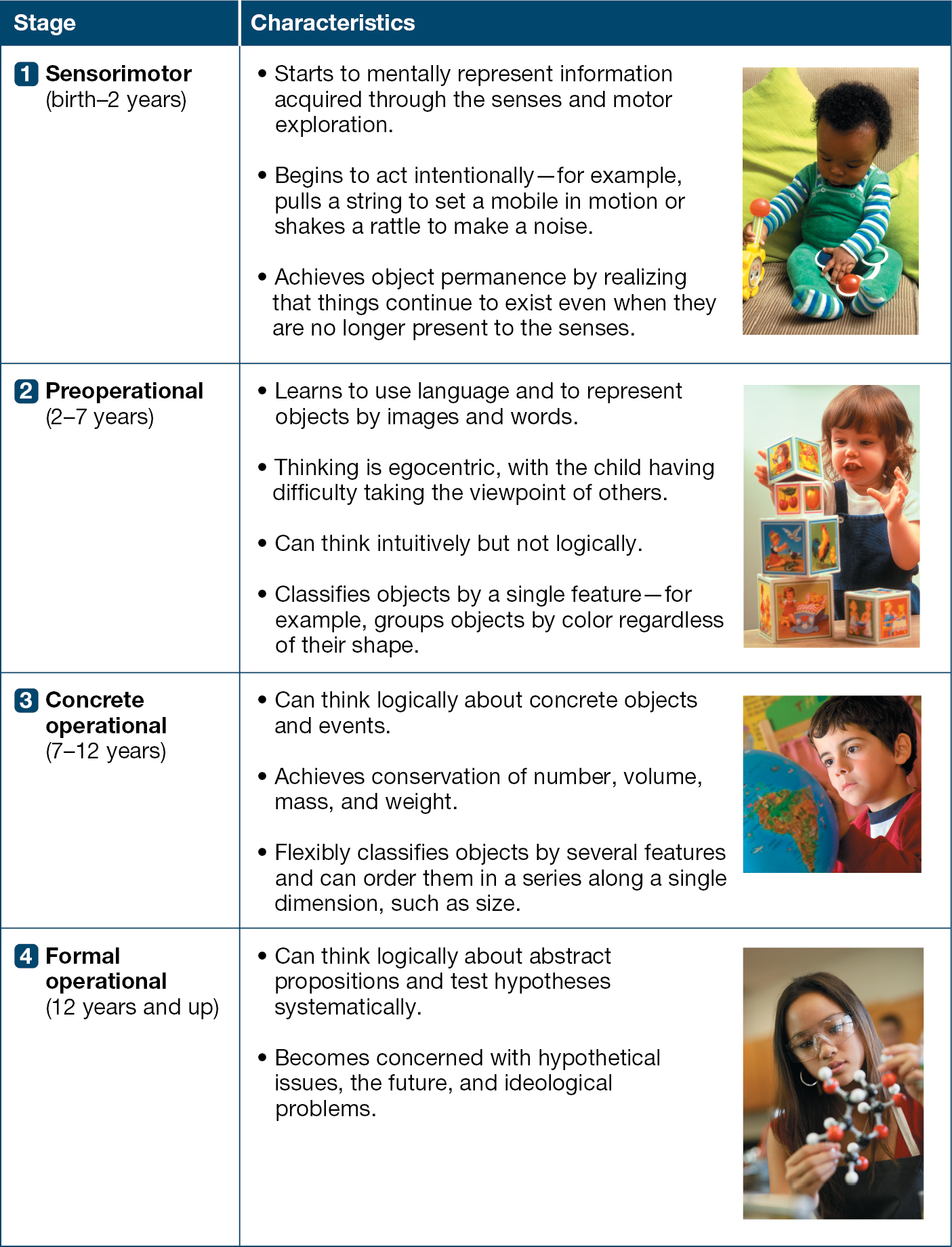

The table has five rows and two columns. The column header reads Stage and Characteristics.

FIGURE 4.15 Piaget’s Four Stages of Cognitive Development

Piaget described children’s thinking abilities across four stages of cognitive development. In which stage do children think intuitively rather than logically?

Sensorimotor Stage: Birth to 2 Years According to Piaget, children from birth until about age 2 are in the sensorimotor stage of cognitive development. During this period, they acquire information primarily through their senses and motor exploration. For example, they first learn reflexively, by sucking on a nipple, grasping a finger, or seeing a face.

As infants begin to control their motor movements, they develop their first schemas. These mental representations contain information about actions that can be performed on certain kinds of objects. For instance, the sucking reflex lets the infants realize they can suck other things, such as a bottle, a finger, a toy, or a blanket. Piaget described sucking other objects as an example of assimilation to the schema of sucking.

According to Piaget, one important cognitive concept developed in this stage is object permanence—the understanding that an object continues to exist even when it is hidden from view. Piaget noted that until 9 months of age, most infants will not search for objects they have watched someone hide under a blanket. At around 9 months, they will look for the hidden object by picking up the blanket. According to Piaget, a child’s full comprehension of object permanence is one key accomplishment of the sensorimotor period.

Preoperational Stage: 2 to 7 Years According to Piaget, children from about 2 to 7 years of age can begin to think about objects not in their immediate view. During this preoperational stage, children begin to think symbolically. For example, they can pretend that a stick is a sword or a wand. However, Piaget believed that children at this stage cannot think operationally—in other words, they cannot imagine the logical outcomes of performing certain actions on certain objects. Instead, they use intuitive reasoning based on superficial appearances. For example, if preoperational children are in a moving car with the sun shining in their eyes, they might complain that the sun is following them.

FIGURE 4.16 Egocentrism

This toddler is playing hide-and-seek with her mother. Because the toddler’s head is in the box and she cannot see her mother, she believes that her mother also cannot see her. The toddler is definitely in the preoperational stage.

Another cognitive characteristic of the preoperational period is egocentrism. Preoperational thinkers generally view the world through their own experiences. Their thought processes tend to revolve around their own perspectives. For example, 2-year-olds may play hide-and-seek by placing boxes over their heads, believing that if they cannot see other people, then other people cannot see them (Figure 4.16). Like Rowen, whom you met at the beginning of this section, egocentric children cannot put themselves in another person’s shoes.

Concrete Operational Stage: 7 to 12 Years At about 7 years of age, according to Piaget, children enter the concrete operational stage. They remain in this stage until adolescence. Piaget believed that humans do not develop logic until they begin to think about and understand operations. A classic operation is an action that can be undone: A light can be turned on and off, a stick can be moved across the table and then moved back, and so on. Children in this stage are not fooled by superficial transformations, such as how the volume of liquid can look different in glasses of varying size. Instead, they can reason logically about problems.

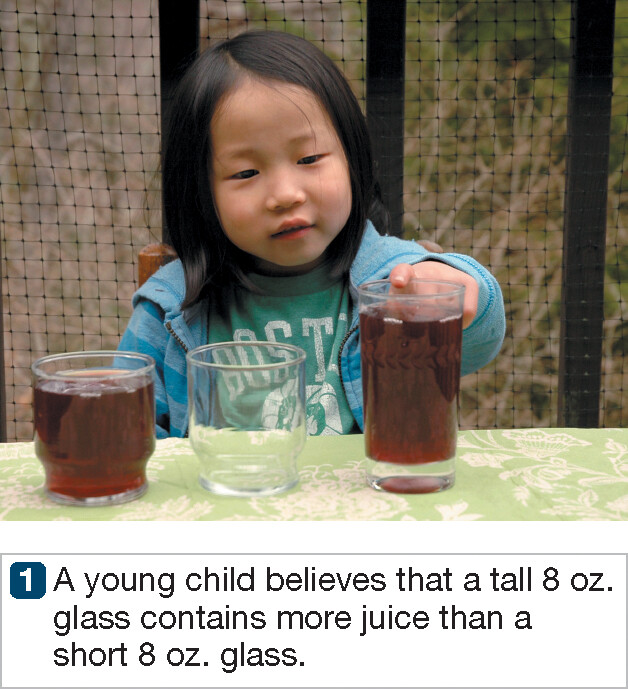

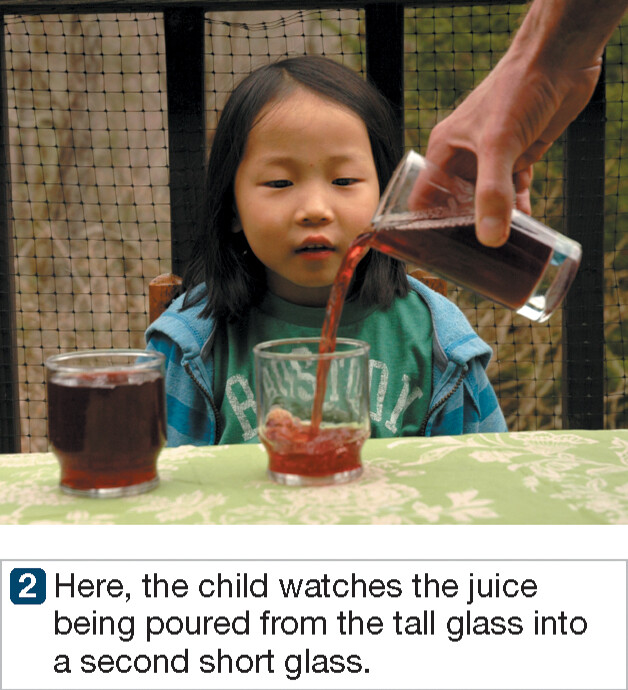

For instance, children at this stage understand the law of conservation. This law states that even if the appearance of a substance changes in one dimension, the properties of that substance remain unchanged. For example, if you pour water from a short, wide glass into a tall, narrow glass, the amount of water does not change. If you ask children in the concrete operational stage which glass contains more water, they will correctly say that both glasses have the same amount of liquid (Figure 4.17). By contrast, children in the preoperational stage will say that the tall, narrow glass contains more water because the water is at a higher level. Preoperational children will make this error even when they have seen someone pour the same amount of water into each glass or when they pour the liquid themselves. They cannot understand that the narrower diameter of the taller glass makes the water level higher.

The first photo depicts a girl looking at three glasses, two of which are filled with water and are the same size and one of which is empty and taller than the other two; the caption reads A child in the concrete operational stage understands that two identical short glasses contain the same amount of water. The second photo depicts the same girl watching one of the filled glasses be poured into the tall glass the caption reads Here, the child observes the water from one of the short glasses poured into the tall, narrower glass. The third photo depicts the girl looking at the filled tall glass next to the filled short glass; the caption reads When asked which one contains more water, the child will know that both glasses hold the same amount of water.

The first photo depicts a girl looking at three glasses, two of which are filled with water and are the same size and one of which is empty and taller than the other two; the caption reads A child in the concrete operational stage understands that two identical short glasses contain the same amount of water. The second photo depicts the same girl watching one of the filled glasses be poured into the tall glass the caption reads Here, the child observes the water from one of the short glasses poured into the tall, narrower glass. The third photo depicts the girl looking at the filled tall glass next to the filled short glass; the caption reads When asked which one contains more water, the child will know that both glasses hold the same amount of water.

The first photo depicts a girl looking at three glasses, two of which are filled with water and are the same size and one of which is empty and taller than the other two; the caption reads A child in the concrete operational stage understands that two identical short glasses contain the same amount of water. The second photo depicts the same girl watching one of the filled glasses be poured into the tall glass the caption reads Here, the child observes the water from one of the short glasses poured into the tall, narrower glass. The third photo depicts the girl looking at the filled tall glass next to the filled short glass; the caption reads When asked which one contains more water, the child will know that both glasses hold the same amount of water.

FIGURE 4.17Conservation Task Based on Volume

According to Piaget, children in the concrete operational stage reason logically, not intuitively as they did in the preoperational stage. As a result, these children can now understand the concept of conservation, which is shown here in a task focusing on the volume of a liquid.

Although using operations is the beginning of logical thinking in the concrete operational stage, Piaget believed that children at this stage reason only about concrete things. That is, they reason about objects they can act on in the world. They are not yet able to reason abstractly, or hypothetically, about what might be possible. Because they cannot do operations “in their heads,” children in first, second, and third grades often use objects to do math. For example, they may use their fingers to add and subtract. By using concrete information, children in this stage can think in much more logical ways than children in the preoperational stage. However, according to Piaget, they cannot truly engage in sophisticated abstract thinking until they reach adolescence.

Formal Operational Stage: 12 Years to Adulthood Piaget’s final stage of cognitive development is the formal operational stage. During this stage, people can reason in sophisticated, abstract ways. Formal operations involve critical thinking, such as the ability to form a hypothesis about something and test the hypothesis through logic. Critical thinking also involves using information to systematically find answers to problems. To study this ability, Piaget gave teenagers and younger children four flasks of colorless liquid and one flask of colored liquid. He then explained that the colored liquid could be obtained by combining two of the colorless liquids. Adolescents, he found, systematically try different combinations to obtain the correct result. Younger children just randomly combine liquids. Adolescents are also able to consider abstract notions and think about many viewpoints at once. This kind of thinking is characterized by an ability to envision the future and predict the consequences of certain actions.

Other Ways of Thinking About Cognitive Development Piaget’s theory revolutionized the understanding of cognitive development. And he was right about many things (Carpendale et al., 2020). For example, infants do learn about the world through sensorimotor exploration. Also, people do move from intuitive, illogical thinking to a more logical understanding of the world. However, modern research has revealed that we have to consider Piaget’s theory with flexibility.

For example, we now know that Piaget underestimated the ages at which certain skills develop. In his various studies, Piaget may have confused infants’ cognitive abilities with their physical capabilities. For this reason, he may have underestimated the age at which some thinking skills develop. For example, when contemporary researchers use age-appropriate methods, they find that object permanence develops in the first few months of life rather than at 8 or 9 months of age, as Piaget thought (Baillargeon, 1987). Similarly, numerous studies have indicated that infants even have a primitive understanding of some of the basic laws of physics (Spelke, 2016).

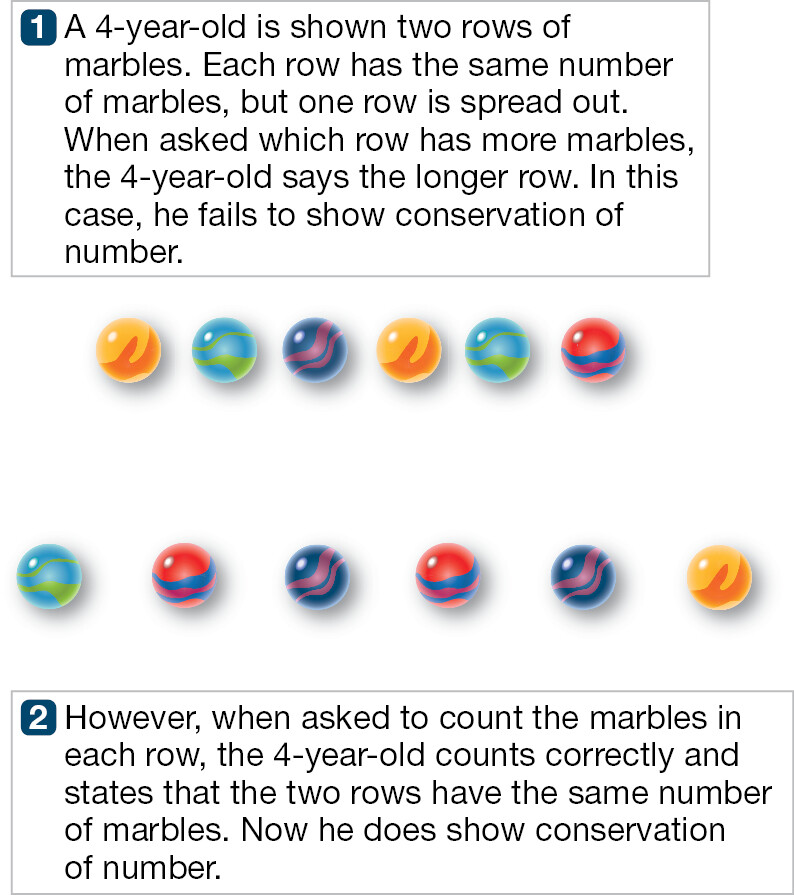

In the first row, there are six marbles close together in a line. In the second row, there are six marbles spread apart in a line. The first caption reads, A 4-year-old is shown two rows of marbles. Each row has the same number of marbles, but one row is spread out. When asked which row has more marbles, the 4-year-old says the longer row. In this case, he fails to show the conservation of numbers. The second caption reads, However, when asked to count the marbles in each row, the 4-year-old counts correctly and states that the two rows have the same number of marbles. Now he does show conservation of numbers.

FIGURE 4.19 Conservation Task Based on Number

When a task is performed in an age-appropriate manner, children are able to show conservation of number at a much younger age than they can show conservation of volume (see Figure 4.17). In which of the tasks shown here does the child show conservation of number?

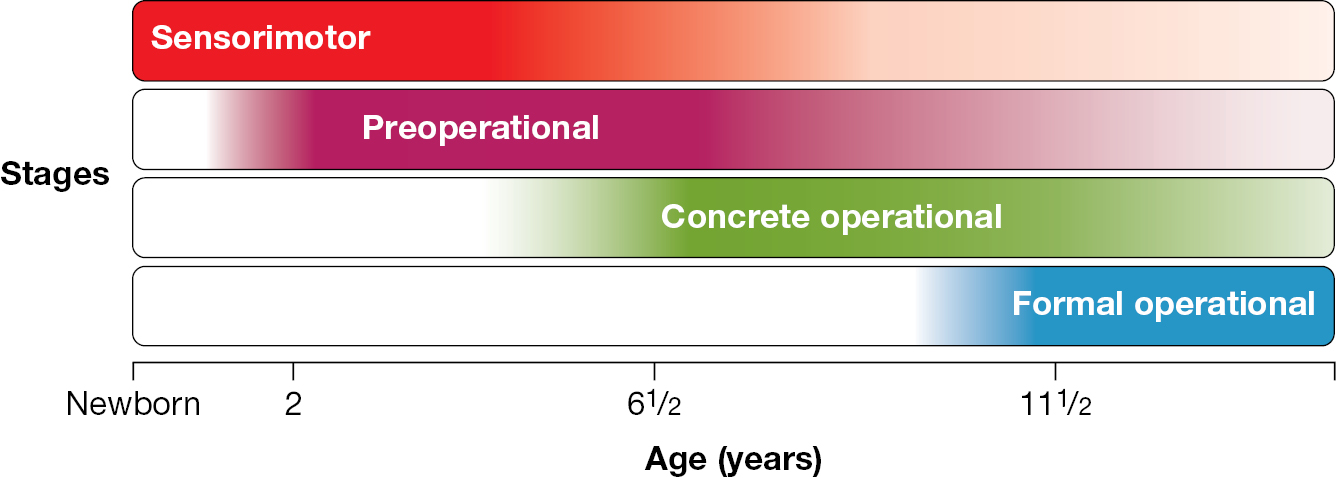

In addition, psychologists now think of cognitive development in terms of trends rather than strict stages. People gradually shift from one or more ways of thinking to other ways of thinking, so they may exhibit skills from different stages simultaneously (Figure 4.18). For example, even though particular children might not understand the conservation of volume (see Figure 4.17), they may be able to perform a conservation task based on number (Figure 4.19). This view of cognitive development is consistent with our understanding of brain development. Cognitive development may not necessarily follow strict and uniform stages, because different areas of the brain are responsible for different skills and these brain areas develop at different rates (Bidell & Fischer, 1995; Case, 1992).

Each stage is represented with a different color but doesn’t have any distinct ends to them. The beginnings are distinct as there is just white before but the ends fade away very slowly and there is some small amount of color through all the years shown (newborn to 15). The higher concentrations of color are associated with being close to Piaget’s stages. The sensorimotor stage is red and the bar is pinkish red up until around 7 years of age when it starts to fade. The preoperational stage is purple and starts around the age of one but it’s not solid purple until the age of two and starts to become less purple around the age of 8. The concrete operational stage is green and it doesn’t start until age 4 but isn’t fully green until 6.5 years of age. The formal operational stage is blue and starts around 10 but doesn’t become solid blue until age 12.

FIGURE 4.18 Trends in Cognitive Development

Modern interpretations view Piaget’s theory in terms of trends, not rigid stages. Children shift gradually in their thinking over a wider range of ages than previously thought, and they can demonstrate the thinking skills of more than one stage at a time.

Some approaches to understanding cognitive development focus on how social and cultural contexts affect the development of cognition and language. According to Lev Vygotsky, a contemporary of Piaget, humans are unique because they use symbols and psychological tools, such as speech, writing, maps, and art. Through these tools, people create culture. In turn, culture dictates what people need to learn and the sorts of skills they need to develop. For example, some cultures value science and rational thinking. Other cultures emphasize supernatural and mystical forces. These cultural values shape how people think about the world around them and relate to it. As children develop, their elementary capacities are gradually shaped by social and cultural contexts (Vygotsky, 1978). Parents, teachers, and older siblings help shape understanding by treating the young child as an apprentice learning the trade of becoming an independent thinker. These more knowledgeable other people provide scaffolding, or basic support and guidance, that helps the child move on to higher levels of thinking (Mermelshtine, 2017; Reynolds, 2021).

Developing Theory of Mind “I know just how you feel,” you say to a friend who is going through a bad breakup. But how do you know your friend’s thoughts or feelings? The ability to understand that other people have mental states that influence their behavior is called theory of mind (Baldwin & Baird, 2001). This ability develops sooner than Piaget’s theory predicts. For instance, beginning in infancy, children come to understand that other people have reasons for performing actions.

In one study that explored theory of mind (Behne et al., 2005), an adult began handing a toy to an infant but then stopped. On some trials, the adult acted unwilling to hand over the toy, teasing the infant with the toy or playing with it. On other trials, the adult became unable to hand it over, “accidentally” dropping it or being distracted by a ringing telephone. Infants older than 9 months showed greater signs of impatience—for example, reaching for the toy—when the adult was unwilling than when the adult was unable. This and other studies provide evidence that infants begin to read other people’s intentions in the first year of life (Brandone et al., 2020). By the end of their second year, perhaps even by 13–15 months of age, young children become very good at reading intentions (Baillargeon et al., 2016).

Part of growing out of egocentrism is recognizing that other people have their own desires, intentions, beliefs, and mental states (Beaudoin et al., 2020). As infants and children acquire theory of mind, they develop the ability to think in increasingly sophisticated ways. For instance, they begin to realize how best to ask their parents for treats, which jokes make other people laugh, and which hiding spots are best for hide-and-seek. By age 4, children understand that someone experiencing pain might like a hug (Decety et al., 2018). The capacity for theory of mind sets the foundation for developing meaningful social relationships with others.

LEARNING GOAL CHECK: REVIEW