EVALUATING THE STRENGTH OF A FINDING

Psychologists, being human, like to brag. They do this when they describe how well their personality measurements can predict behavior and also when they talk about the strength of other research findings. Often—probably too often—they use words such as “large,” “important,” or even “dramatic.” Nearly always, they describe their results as “significant.” These descriptions can be confusing because there are no rules about how the first three terms can be employed. “Large,” “important,” and even “dramatic” are just adjectives and can be used at will. However, there are formal and rather strict rules about how the term significant can be employed.

Significance Testing

A significant result, in research parlance, is not necessarily large or important, let alone dramatic. But it is a result that would be unlikely to appear if everything were due only to chance. This is important, because in any experimental study the difference between conditions will almost never11 turn out to be exactly zero, and in correlational studies finding a precisely zero relation between X and Y is equally rare. So, how large does the difference between the means of two conditions have to be, or how big does the correlation need to be, before we will conclude that these are numbers we should take seriously?

The most commonly used method for answering this question is null-hypothesis significance testing (NHST). NHST attempts to answer the question, “What are the chances I would have found this result if in fact nothing were really going on?” The basic procedure is taught in every beginning statistics class. A difference between experimental conditions or a correlation coefficient is said to be “significant” if it’s so large that it’s unlikely to have happened just by chance. Researchers employ various statistical formulas, some quite complex, to calculate just how unlikely. The answer is expressed as a probability called the p-level.

For example, look back at the results in Figures 3.4 and 3.5. These findings might be evaluated by calculating the p-level of the difference in means (in the experimental study in Figure 3.4) or of the correlation coefficient (in the correlational study in Figure 3.5). In each case, the p-level is the probability that a difference of that size (or larger) would be found, if the actual size of the difference were zero. (This possibility of a zero result is called the null hypothesis.) If the result is significant, the common interpretation is that the statistic probably did not arise by chance; its real value, sometimes called the population value, is probably not zero, so the null hypothesis is incorrect, and the result is big enough to take seriously.

This traditional method of statistical data analysis is deeply embedded in the scientific literature and current research practice and is almost universally taught in beginning statistics classes. But I would not be doing my duty if I failed to warn you that insightful psychologists have been critical of this method for many years (e.g., Rozeboom, 1960), and the frequency and intensity of this criticism have only increased over time (e.g., Cumming, 2012, 2014; Dienes, 2011; Haig, 2005). Indeed, some psychologists have long suggested that conventional significance testing should be banned altogether (Hunter, 1997; F. L. Schmidt, 1996)! That may be going a bit far, but NHST does have some serious problems. This chapter is not the place for an extended discussion, but it might be worth a few words to describe some of the more obvious difficulties (see also Cumming, 2014; Dienes, 2011).

One problem with NHST is that the underlying logic is difficult to describe precisely, and its interpretation—including the interpretation given in many textbooks—is frequently wrong. It is not correct, for example, that the significance level provides the probability that the research (non-null) hypothesis is true. A significance level of .05 is sometimes taken to mean that the probability that the research hypothesis is true is 95 percent! Nope. I wish it were that simple. Instead, the significance level gives the probability of getting the result one found if the null hypothesis were true. One statistical writer offered the following analogy (Dienes, 2011): The probability that a person is dead, given that a shark has bitten the person’s head off, is 1.0. However, the probability that a person’s head was bitten off by a shark, given that the person is dead, is much lower. Most people die in less dramatic fashion. The probability of the data given the hypothesis, and of the hypothesis given the data, is not the same thing. And the latter is what we really want to know.

Believe it or not, I really did try to write the preceding paragraph as clearly as I could, and I even included a vivid example concerning a shark to illustrate the point. But if you still found the paragraph confusing, you are in good company. One study found that 97 percent of academic psychologists, and even 80 percent of methodology instructors, misunderstood NHST in an important way (Krauss & Wassner, 2002). The most widely used method for interpreting research findings is so confusing that even experts often get it wrong. This cannot be a good thing.

Traditional significance tests have one final problem: The p-level addresses only the probability of one kind of error, conventionally called a Type I error. A Type I error involves deciding that one variable has an effect on, or a relationship with, another variable, when really it does not. But there is another kind: A Type II error involves deciding that one variable does not have an effect on, or relationship with, another variable, when it really does. Unfortunately, there is no way to estimate the probability of a Type II error without making extra assumptions (Cohen, 1994; Dienes, 2011).

What a mess. The bottom line is this: When you take a course in psychological statistics, if you haven’t already, you will probably have to learn about significance testing and how to do it. Despite its many and widely acknowledged flaws, NHST remains in wide use and, for better or worse, seems firmly cemented in the foundation of research methodology (Krauss & Wassner, 2002). But it is not as useful a technique as it looks at first, and psychological research practice seems to be moving slowly, ever so slowly, but surely away (Cumming, 2014). The p-level at the heart of NHST is not completely useless; it can serve as a rough guide to the strength of one’s results (J. I. Krueger & Heck, 2018). However, sooner or later, evaluating research will come to focus less on statistical significance and more on effect size and replication, the two topics to be considered next.

Effect Size

All scientific findings are not created equal. Some are bigger than others, which raises a question that must be asked about every result: How big is it? Is the effect or the relationship we have found strong enough to matter, or is its size too trivial to care about? Because this is important to know, psychologists who are better analysts of data do not just stop with significance. They move on to calculate a number that will reflect the magnitude, as opposed to the likelihood, of their result. This number is called an effect size (Grissom & Kim, 2012).

An effect size is more meaningful than a significance level. Don’t take my word for it; the principle is official: The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, which sets the standards that must be followed by almost all published research in psychology, explicitly says that the probability value associated with statistical significance does not reflect “the magnitude of an effect or the strength of a relationship. For the reader to fully understand the magnitude or importance of a study’s findings, it is almost always necessary to include some index of effect size” (American Psychological Association, 2010, p. 34).

Many measures of effect size have been developed, including standardized regression weights (beta coefficients), odds ratios, relative risk ratios, and a statistic called Cohen’s d (the difference in means divided by the standard deviation). The most commonly used and my personal favorite is the correlation coefficient. Despite the name, its use is not limited to correlational studies. As we saw earlier in this chapter, the correlation coefficient can be used to describe the strength of either correlational or experimental results (Funder & Ozer, 1983).

CALCULATING CORRELATIONS

To calculate a correlation coefficient, in the usual case, you start with two variables, and arrange the scores into columns, with each row containing the pair of scores for one participant. These columns are labeled x and y. Traditionally, the variable you think is the cause (or the IV) is put in the x column and the variable you think is the effect (or the DV) is put in the y column. So, in the example considered earlier in this chapter, x was “anxiety” and y was “performance.” Then you apply a common statistical formula (found in any statistics textbook) to these numbers or, more commonly, you punch the numbers into a computer or maybe even a handheld calculator.12

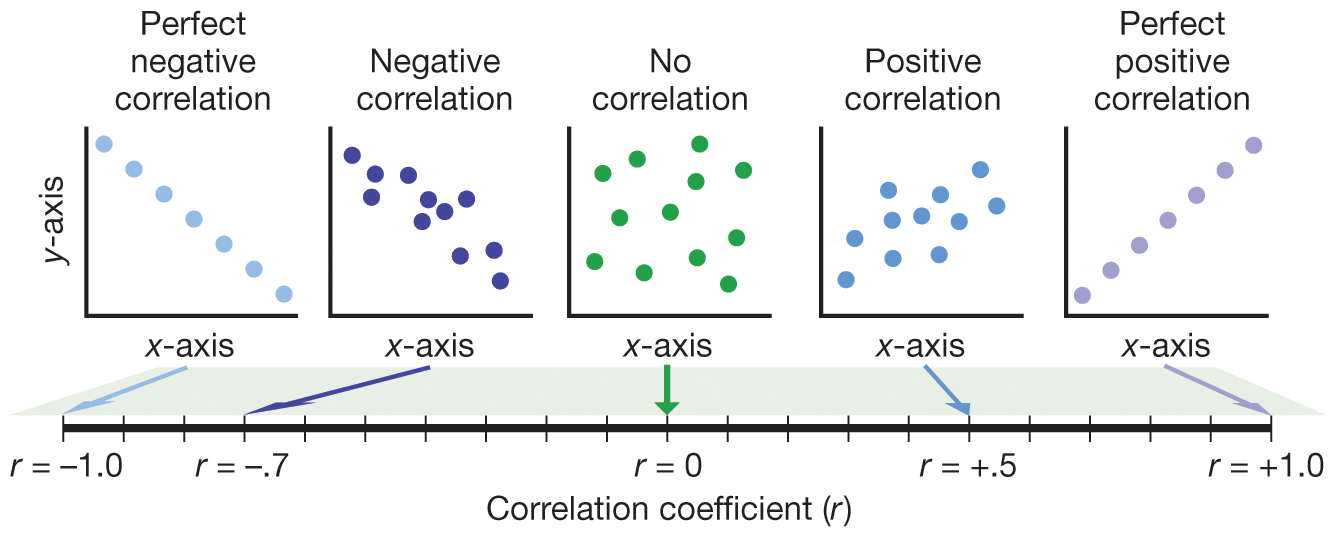

The result is a correlation coefficient (the most common is the Pearson r). This is a number that—if you did the calculations right—is somewhere between +1 and –1 (Figure 3.6). If two variables are unrelated, the correlation between them will be near zero. If the variables are positively associated—that is, as one goes up, the other tends to go up too, like height and weight—then the correlation coefficient will be greater than zero (i.e., a positive number). If the variables are negatively associated—that is, as one goes up, the other tends to go down, like anxiety and performance in the example we used earlier—then the correlation coefficient will be less than zero (i.e., a negative number). Essentially, if two variables are correlated (positively or negatively), this means that one of them can be predicted from the other. For example, Figure 3.5 showed that if I know how anxious you are, then I can predict (to a degree) how well you will do on a math test.

More information

Five scatter plots are shown, each representing a different correlation. A perfect negative correlation occurs on a scatter plot that has a negative slope and has a correlation coefficient of negative 1.0. A negative correlation occurs on a scatter plot that has a negative slope and has negative correlation coefficient. No correlation occurs when the scatter plot has no general trend, and the correlation coefficient is zero. A positive correlation occurs on a scatter plot that has a positive slope and has positive correlation coefficient. A perfect positive correlation occurs on a scatter plot that has a positive slope and has a correlation coefficient of 1.0. Below the scatter plots is a number line showing the different values of correlation coefficients that range from negative 1.0 to 1.0.

CONFIDENCE INTERVALS

Researchers routinely report the statistical significance of correlations, but we’ve already seen some of the problems with that practice. A better although related approach is to calculate the confidence interval of the correlation, which can tell you given certain statistical assumptions the range of values within which the true or population correlation is likely to be found. For example, if a researcher finds a correlation of .30 in a sample of 200 participants, the 95 percent confidence interval ranges from .17 to .42, meaning that correlation in the wider population has a 95 percent chance of being in that range—or, to put it another way, a 5 percent chance of being outside that range.13

INTERPRETING CORRELATIONS

Once you’ve got an estimate of the size of a correlation, and even a confidence interval that tells you how precise this estimate is, you are still left with one more question: Is this correlation big or little?

One commonly taught but, in my opinion, misleading way to evaluate correlations is to square them,14 which tells “what percent of the variance the correlation explains.” This certainly sounds like what you need to know, and the calculation is wonderfully easy. For example, a correlation of .30, when squared, yields .09, which means that “only” 9 percent of the variance is explained by the correlation, and the remaining 91 percent is “unexplained.” Similarly, a correlation of .40 means that “only” 16 percent of the variance is explained and 84 percent is unexplained. That seems like a lot of unexplaining, and so such correlations are often viewed as small.

Yet, this conclusion is not correct (Ozer, 1985).15 Worse, it is almost impossible to understand. We need a better way to evaluate the size of correlations. A suggestion that I and my longtime colleague Dan Ozer have proposed is a very loose rule of thumb: A correlation of .05 is very small, .10 is small, .20 is medium, .30 is large, and .40 is very large (Funder & Ozer, 2019). Moreover, even small effects by these standards can be important as they accumulate over time. The correlation between a single at-bat and getting a hit for a Major League player is r = .06, yet across a long season this difference can add up to a huge effect on win–loss records and millions of dollars in player salaries (Abelson, 1985). Similarly, personality traits that have seemingly small effects day-to-day can accumulate to important long-term differences in life outcomes. Be just a little bit friendlier to people every day; over time you will become a more popular person. I promise.

Replication

Beyond the size of a research result, no matter how it is evaluated, is a second and even more fundamental question: Is the result dependable, something you could expect to find again and again, or did it merely occur by chance? As was discussed previously, null-hypothesis significance testing (NHST) is traditionally used to answer this question, but it is not really up to the job. A much better indication of the stability of results is replication. In other words, do the study again. Statistical significance is all well and good, but there is nothing quite as persuasive as finding the same result repeatedly, with different participants and in different labs (Asendorpf et al., 2013; Funder et al., 2014).16

The principle of replication seems straightforward, but it has led to a remarkable degree of controversy—not just within psychology but also in many areas of science. One early spark was an article, written by a prominent medical researcher and statistician, entitled “Why most published research findings are false” (Ionnadis, 2005). That title certainly got people’s attention! The article focused on biomedicine but addressed reasons why findings in many areas shouldn’t be completely trusted. These reasons include the proliferation of small studies with weak findings, researchers reporting only selected analyses rather than everything they find, and the undeniable fact that researchers are rewarded with grants and jobs for studies that get interesting results. Another factor is publication bias, in which studies with strong results are more likely to be published than studies with weak results, leading to a research literature that makes effects seem stronger than they really are (Polanin et al., 2016).

Worries about the truth of published findings spread to psychology a few years later, in a big way, when three things happened almost at once. First, an article in the influential journal Psychological Science illustrated how researchers could make almost any data set yield significant findings through techniques such as deleting unusual responses, adjusting results to remove the influence of seemingly extraneous factors, and neglecting to report experimental conditions or even whole experiments that fail to get expected results (Simmons et al., 2011). Such questionable research practices (QRPs) have also become known as p-hacking, a term that refers to hacking around in one’s data, running one analysis after another, until one finds the necessary degree of statistical significance, or p-level, that allows the findings to be published. To demonstrate how this could work, Simmons and his team massaged a real data set to “prove” that listening to the Beatles song “When I’m 64” actually made participants younger!

Coincidentally, at almost exactly the same time, the prominent psychologist Daryl Bem published an article in a major journal purporting to demonstrate a form of ESP called “precognition,” reacting to stimuli presented in the future (Bem, 2011). And then, close on the heels of that stunning event, another well-known psychologist, Diederik Stapel, was exposed for, quite literally, faking his data, writing down and erasing data points so that his studies always worked (Bhattacharjee, 2013). The two cases of Bem and Stapel were different because nobody suggested that Bem committed fraud, but nobody seemed to be able to repeat his findings either, suggesting that flawed (but common) practices of data analysis were to blame (Wagenmakers et al., 2011). For example, it was suggested that Bem might have published only the studies that successfully demonstrated precognition, not the ones that failed. One thing the two cases did have in common was that the work of both researchers had passed through the filters of scientific review that were supposed to ensure that published findings can be trusted.

And this was just the beginning. Before long, one widely accepted finding in psychology after another became called into question as researchers found that they were unable to repeat it in their own laboratories (Open Science Collaboration, 2015). One example is a study that I happily (and credulously) described in previous editions of this very book, a study that purported to demonstrate a phenomenon sometimes called “elderly priming” (Z. Anderson, 2015; Bargh et al., 1996). College student participants were “primed” with thoughts about old people by having them unscramble words such as “DNLIRKWE” (wrinkled), “LDO” (old), and (my favorite) “FALODRI” (Florida). Others were given scrambles of neutral words such as “thirsty,” “clean,” and “private.” The remarkable—even forehead-slapping—finding was that when they walked away from the experiment, participants in the first group moved more slowly than participants in the second group! Just being subtly reminded about concepts related to being old, it seemed, is enough to make a person act old.

I reported this fun finding in previous editions because the measurement of walking speed seemed like a great example of B-data, as described in Chapter 2, and also because I thought readers would enjoy learning about it. That was my mistake! The original study was based on just a few participants17 and later attempts to repeat the finding, some of which used much larger samples, were unable to do so (e.g., Z. Anderson, 2015; Doyen et al., 2012). In retrospect, I should have known better. Not only were the original studies very small, but also the finding itself is so remarkable that extra-strong evidence should have been required before I believed it.18 Findings that seem too good to be true, to psychologists and non-psychologists alike, tend to be the ones least likely to replicate (Hoogeveen et al., 2020).

By now, this pattern has emerged over and over: An intriguing finding is published and gets a lot of attention, and even makes it into textbooks. Then follow-up studies show that the finding is difficult or impossible to replicate. And then, sadly, more often than not, the follow-up studies are largely ignored! One recent wide-ranging review reported that findings shown to be non-replicable continue to be cited anyway at almost the same pace as before (P. T. von Hippel, 2022).

Scientific conclusions are the best interpretations that can be based on the evidence at hand. But they are always subject to change.

The questionable validity of the many findings that researchers tried and failed to replicate stimulated lively and sometimes acrimonious exchanges in forums ranging from academic symposia and journal articles to impassioned tweets, blogs, and Facebook posts.19 At one low point, a prominent researcher complained that colleagues attempting to evaluate replicability were “shameless little bullies.” But over time, cooler heads prevailed, and insults gave way to positive recommendations for how to make research more dependable (Funder et al., 2014; Shrout & Rodgers, 2018). These recommendations include using larger numbers of participants than have been used traditionally, disclosing all methods, sharing data, and reporting studies that don’t work, not just the ones that do (these are core tenets of what has become known as “open science,” considered later in this chapter). The most important recommendation—and one that really should have been followed all along—is to never regard any one study as conclusive proof of anything, no matter who did the study, where it was published, or what its p-level was (Donnellan & Lucas, 2018). The key attitude of science is—or should be—that all knowledge is provisional. Scientific conclusions are the best interpretations that can be based on the evidence at hand. But they are always subject to change.

Glossary

- Type I error

- In research, the mistake of thinking that one variable has an effect on, or relationship with, another variable, when really it does not.

- Type II error

- In research, the mistake of thinking that one variable does not have an effect on or relationship with another, when really it does.

- effect size

- A number that reflects the degree to which one variable affects, or is related to, another variable.

- correlation coefficient

- A number between –1 and +1 that reflects the degree to which one variable, traditionally called y, is a linear function of another, traditionally called x. A negative correlation means that as x goes up, y goes down; a positive correlation means that as x goes up, so does y; a zero correlation means that x and y are unrelated.

- confidence interval

- An estimate of the range within which the true value of a statistic probably lies.

- replication

- Doing a study again to see if the results hold up. Replications are especially persuasive when done by different researchers in different labs than the original study.

- publication bias

- The tendency of scientific journals preferentially to publish studies with strong results.

- questionable research practices (QRPs)

- Research practices that, while not exactly deceptive, can increase the chances of obtaining the result the researcher desires. Such practices include deleting unusual responses, adjusting results to remove the influence of seemingly extraneous factors, and neglecting to report variables or experimental conditions that fail to yield expected results. Such practices are not always wrong, but they should always be questioned.

- p-level

- In null hypothesis statistical testing, the calculated probability that an effect of the size (or larger) obtained by a study would have been found if the actual effect in the population were zero.

- p-hacking

- Analyzing data in various ways until one finds the desired result.

Endnotes

- Actually, never.Return to reference 11

- Programs to calculate the correlation coefficient are also available online. One easy to use and free calculator can be found at https://www.socscistatistics.com/tests/pearson/default2.aspx.Return to reference 12

- An easy to use online calculator for confidence intervals is at https://www.statskingdom.com/correlation-confidence-interval-calculator.html.Return to reference 13

- The reason for doing this has to do with converting variation, which is deviation from the mean, into variance, which is squared deviation from the mean.Return to reference 14

-

I have found that many of my colleagues, with PhD’s in psychology themselves, resist accepting this fact because of what they were taught in their first statistics course long ago. All I can do is urge that they read the Ozer (1985) paper just referenced. To encapsulate the technical argument, “variance” is the sum of squared deviations from the mean; the squaring is a computational convenience but has no other rationale. However, one consequence is that the variance explained by a correlation is in squared units, not the original units that were measured. To get back to the original units, just leave the correlation unsquared. Then, a correlation of .40 can be seen to explain 40 percent of the (unsquared) variation, as well as 16 percent of the (squared) variance.Return to reference 15

- R. A. Fisher, usually credited as the inventor of NHST, wrote “we may say that a phenomenon is experimentally demonstrable when we know how to conduct an experiment that will rarely fail to give us a statistically significant result” (1966, p. 14).Return to reference 16

- Actually, there were two studies, each with 30 participants, which is a very small number by any standard.Return to reference 17

- The twentieth-century astronomer Carl Sagan popularized the phrase “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence,” but David Hume wrote back in 1748 that “No testimony is sufficient to establish a miracle, unless the testimony be of such a kind, that its falsehood would be more miraculous than the fact which it endeavors to establish” (Rational Wiki, 2018).Return to reference 18

- As we all know, tweets, blogs, and Facebook posts don’t always bring out the best in people.Return to reference 19