THE ACCURACY OF PERSONALITY JUDGMENT

People are constantly making personality judgments, and these judgments are consequential. Judgments of the personalities of others influence who you will befriend, date, hire, or avoid. Judgments of your own personality will affect what you attempt to accomplish and your view of your own worth (self-esteem, see Chapter 14). Therefore, it’s important to know when and to what degree these judgments are accurate.

It might surprise you, therefore, to learn that for an extended period of time (about 30 years) many psychologists went out of their way to avoid researching accuracy. Although research on the topic was fairly active from the 1930s to about 1955, after that the field fell into a lull, from which it began to emerge only in the mid-1980s (Funder & West, 1993).

There are several reasons why research on accuracy experienced this lengthy hiatus (Funder, 1995; Funder & West, 1993). The most basic reason is that researchers were stymied by a fundamental problem: How can personality judgments be judged as right or wrong (Hastie & Rasinski, 1988; Kruglanski, 1989)? Some psychologists believed this question was unanswerable because any attempt to answer it would simply pit one person’s assessment of accuracy against another’s. Who decides which is right?

This point of view was bolstered by the philosophy of constructivism, which is widespread throughout modern intellectual life (Stanovich, 1991). Slightly simplified, this philosophy holds that reality, as a concrete entity, does not exist. All that does exist are human ideas, or constructions, of reality. This view finally settles the age-old question, “If a tree falls in the forest with no one to hear, does it make a noise?” The constructivist answer: No. A more important implication is that there is no way to regard one interpretation of reality as accurate and another interpretation as inaccurate, because all interpretations are mere social constructions.

“If a tree falls in the forest with no one to hear, does it make a noise?” The constructivist answer: No.

This idea that, since there is no reality, judgmental accuracy cannot be assessed meaningfully is still quite fashionable in certain intellectual circles.8 Nevertheless, I reject it (Funder, 1995). I find the philosophical outlook of critical realism more reasonable (Rorer, 1990). This philosophy prescribes that you gather all the information that might help you determine whether or not the judgment is valid and then make the best determination you can. The task remains perfectly reasonable, even necessary, though the accuracy of the outcome will always be uncertain (Cook & Campbell, 1979; Cronbach & Meehl, 1955).

Criteria for Accuracy

There is a simpler way to think of this issue. A personality judgment rendered by an acquaintance or a stranger can be thought of as a kind of personality assessment or even a personality test of the sort considered in Chapter 2. If you think of a personality judgment as a test, then the considerations discussed in the previous two chapters immediately come into play. Assessing the accuracy of a personality judgment becomes equivalent to assessing the validity of a personality test. And there is a well-developed and widely accepted method for that.

The method is called convergent validation. It can be illustrated by the duck test: If it looks like a duck, walks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, it is very probably—but still not absolutely positively—a duck. (Maybe it’s a sophisticated Disney audio-animatronic machine built to resemble a duck, but probably not.) Convergent validation is achieved by assembling diverse pieces of information, such as appearance, walking and swimming style, and quackiness, that “converge” on a common conclusion: Beyond a reasonable doubt, it’s a duck. The more items of diverse information that converge, the more confident the conclusion (J. Block, 1989, pp. 236–237).

More information

A photo shows two ducks in a pond.

For personality judgments, the two primary converging criteria are interjudge agreement and behavioral prediction. If I judge you to be highly conscientious, and so do your parents, and so do your friends, and so do you, it is more likely than not—though not certain—that you are highly conscientious. Moreover, if my judgment that you are highly conscientious converges with the subsequent empirical fact that you arrive on time for almost all your class meetings for the next three semesters, thereby demonstrating predictive validity, then my judgment of you is even more probably correct (although 100 percent certainty is never attained).

In sum, psychological research can evaluate personality judgments by asking two questions (Funder, 1987, 1995, 1999): (1) Do the judgments agree with one another? (2) Can they predict behavior? So, let’s use these criteria to evaluate accuracy in various circumstances, beginning at the beginning, with first impressions.

First Impressions

As soon as you meet a person, you start to make judgments of their personality—and they are doing exactly the same thing to you. Neither of you can really help it. Personality judgments are made quickly and almost automatically (Hassin & Trope, 2000). You have no doubt heard the cliché that a person doesn’t get a second chance to make a first impression. Are such first impressions at all accurate?

One early study found that after undergraduates sat together in small groups for 15 minutes without talking, their ratings of each other correlated better than r = .30 on the traits of extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness to experience (Passini & Norman, 1966). Turning again to the Binomial Effect Size Display (BESD) described earlier, this means that rating a stranger in this situation on these three traits is about twice as likely to be right as wrong (Table 4.3). Other studies also suggest that first impressions have some validity. A glance at someone’s face can be enough to make surprisingly accurate judgments of the degree to which someone is dominant or submissive (D. S. Berry & Wero, 1993), their sexual orientation (Rule & Ambady, 2008a), or even, in the case of business executives, how much profit their company makes (Rule & Ambady, 2008b).

Table 4.3 ACCURACY OF STRANGERS’ JUDGMENT OF PERSONALITY

|

Self-Judgment |

|||

|

Others’ Judgment |

High |

Low |

Total |

|

High |

65 |

35 |

100 |

|

Low |

35 |

65 |

100 |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

200 |

Note: These are results of a hypothetical study with 200 participants, where self–other r = .30.

How is this degree of accuracy possible? Apparently, there really are configural aspects of the face that allow a number of psychological aspects to be judged with a degree of validity, although it seems to be difficult, if not impossible, to say exactly what these are. Mysterious, right? Still, the message is that the human face contains far more information about personality than psychologists would have guessed just a few years ago. This fact may be one reason that research has shown that job interviews done over the telephone are not as valid for judging personality as those that are conducted face-to-face (Blackman, 2002a, 2002b). Now, of course, many interviews are conducted virtually via Zoom and other platforms that share video images. Are they as good as interviews done in person? As of now, we don’t know; more research really is needed.9

Moderators of Accuracy

When is accuracy more or less likely? The answer depends on several influences that in psychological parlance are called moderator variables. Research has focused on four potential moderator variables that make accurate judgments of personality more or less likely: (1) the judge, (2) the target (the person who is judged), (3) the trait that is judged, and (4) the information on which the judgment is based.

THE GOOD JUDGE

The oldest question in accuracy research is this: Who are the best judges of personality? Numerous studies tackled this question during the pre-1955 wave of research (Taft, 1955). A satisfying answer turned out to be surprisingly elusive. Early studies found that a good judge in one context or of one trait might not be a good judge in other contexts or with other traits. Disappointment with this vague conclusion may be one reason why the first wave of accuracy research waned in the mid-1950s (Funder & West, 1993). But the pessimism was probably premature, because the original research was conducted using inadequate statistical methods (Colvin & Bundick, 2001; Cronbach, 1955).

The later wave of accuracy research addressed a variety of interesting questions. For example, who are the better judges of personality, women or men? In a study that gathered personality ratings from strangers who sat around a table together for a few minutes but had no chance to speak, women were better than men at judging two traits (extraversion and positive emotionality) but not others (Ambady et al., 1995). A further study in which groups including men and women had a chance to interact found that women were generally more accurate in overall judgments, but only because they had a more accurate view of what the “normative” or average person is like (M. Chan et al., 2011). Overall, a review of the relevant research has concluded that, although the difference is not large, women are usually better judges of people (Hall et al., 2016).

Good judges of personality may be more positive in general. People whose typical or “stereotypic” judgments tend to describe others in favorable terms also tend to be more accurate, because most people actually are generally honest, friendly, kind, and helpful, which is nice to know (Vogt & Colvin, 2003). Therefore, the positive outlook on life that is characteristic of people who are psychologically well adjusted can lead them to be better judges of others (Human & Biesanz, 2011b). Good judges also have greater “cardiac vagal flexibility,” which is a measure of heart function associated with social sensitivity10 (Human & Mendes, 2018), and they also score higher on a test of “dispositional intelligence” (Table 4.4). On the flip side, judges characterized by the “dark triad” traits of psychopathy, Machiavellianism (manipulativeness), and sadism11 tend to judge people both negatively and inaccurately (K. H. Rogers et al., 2018).

Table 4.4 SAMPLE ITEMS FROM A TEST OF DISPOSITIONAL INTELLIGENCE

|

1. Coworkers who tend to express skepticism and cynicism are also likely to: a. Have difficulty imagining things b. Get upset easily c. Dominate most interactions d. Exhibit condescending behavior |

|

2. A teacher who has a tendency to discuss philosophical issues is likely to: a. Make plans and stick to them b. Do things by the book c. Come up with bold plans d. Prefer to deal with strangers in a formal manner |

|

3. Which of the following situations is most relevant to the trait of sociability?

a. A week after taking a final exam, you go to the professor’s office to find out your final grade and you run into a classmate there. While you are both waiting for your grades, your classmate tells you he found the course difficult and is concerned about his performance. b. You have just heard that your supervisor received a promotion that your supervisor has wanted for a long time. c. Over the last two years, you have been employed at a job that entails working by yourself. Your boss offers you a chance to do essentially the same thing but in a group of coworkers. |

|

4. Which of the following situations is most relevant to the trait of empathy?

a. You bump into the athlete you know was largely responsible for the team losing a recent game. b. Some of your friends have just told you they are planning to go skydiving and have signed up for a free introductory jump. c. Over the last two years, you have been employed at a job that entails working by yourself. Your boss offers you a chance to do essentially the same thing but in a group of coworkers. |

ANSWERS: 1 (d); 2 (c); 3 (c); 4 (a). The complete test has 45 items.

Source: Christiansen et al. (2005), pp. 148–149.

Maybe it’s more important to understand normal people than it is to understand unusual people, because most people are by definition normal.

A final question is: What use is it to be a good judge of personality? It is easy to imagine specific cases where it’s important to be right, when deciding whether to loan somebody some money or when choosing a roommate, for example. But little research, so far, has investigated the general benefits of being a good judge. One study found, perhaps surprisingly, that being a good judge of “distinctive” aspects of personality, of being able to distinguish how people are different from each other, didn’t seem very useful. But people who were better “normative” judges of personality, meaning that they correctly understood what most people are like, were more likely to enjoy outcomes such as better interpersonal control, more support from other people, positive emotional experiences, and satisfaction with life (Letzring, 2015). Maybe it’s more important to understand normal people than it is to understand unusual people, because most people are by definition normal.

THE GOOD TARGET

When it comes to accurate judgment, who is being judged might be even more important than who is doing the judging. An intriguing analysis by Canadian psychologists Lauren Human and Jeremy Biesanz appears to show just that (Figure 4.3). People differ quite a lot in how accurately they can be judged. Everyday experience would seem to bear this out. Some people seem as readable as an open book, whereas others seem more closed and enigmatic. Why? Or, as the classic personality psychologist Gordon Allport asked in this context, “Who are these people?” (Allport, 1937, p. 443; Colvin, 1993).

More information

Two bell curves show the degree of individual difference in a good judge and a good target. For the first graph, the x-axis is labeled “good judge slope” and the y-axis is labeled “density”. The slope is tall and thin with a sigma-hat of .04. For the second graph, the x-axis is labeled “good target slope” and the y-axis is labeled density. The slope is shorter and wider with a sigma-hat of .20.

Source: Human & Biesanz (2013), p. 249.

More information

A photo shows a headshot of psychologist Lauren Human.

According to psychologist Lauren Human (Figure 4.4), “judgable” people are those about whom others reach agreement most easily, because they are the ones whose behavior is most predictable from judgments of their personalities (Human et al., 2014). In other words, judgability is a matter of “what you see is what you get.” The behavior of judgable people is organized coherently; even acquaintances who know them in separate settings describe essentially the same person (Wallace & Biesanz, 2020). Furthermore, the behavior of such people is consistent; what they do in the future can be predicted from what they have done in the past. We could say that these individuals are stable and well organized, or even that they are psychologically well adjusted (Colvin, 1993; Human et al., 2014).12 Judgable people also tend to be extraverted and agreeable (Ambady et al., 1995), although there are sometimes disadvantages to being extraverted. Extraverts sometimes just talk too much and listen too little, which can get in the way of them accurately judging the people they are talking with (Cochran et al., 2018).

Theorists have long postulated that it is psychologically healthy to conceal as little as possible from those around you and to manifest the real you, what is sometimes called the “transparent self” (Jourard, 1971). If you exhibit a psychological façade that produces large discrepancies between the person “inside” and the person you display “outside,” you may feel isolated from the people around you, which can lead to unhappiness, hostility, and depression. Acting in a way that is contrary to your real personality is a lot of work and can be psychologically exhausting (Gallagher et al., 2011). Evidence even suggests that concealing emotions may be harmful to physical health (D. S. Berry & Pennebaker, 1993; Pennebaker, 1992).

Judgability itself—that is, the “what you see is what you get” factor—might be a part of psychological adjustment precisely because it stems from behavioral coherence and consistency.13 As a result, even new acquaintances of judgable people are able to accurately judge otherwise difficult-to-observe attributes such as “remains calm in tense situations,” “does a thorough job,” and “has a forgiving nature” (Human & Biesanz, 2011a).

More information

A sketch depicts a portrait of a person. On the right half of the portrait, the face appears with normal characteristics of eyes, ears, nose, and mouth. The left half is distorted and no key features can be detected.

THE GOOD TRAIT

All traits are not created equal—some are much easier to judge accurately than others. For example, more easily observed traits, such as “talkativeness,” “sociability,” and other traits related to extraversion, are judged with much higher levels of interjudge agreement than are less visible traits, such as cognitive and ruminative styles and habits (Funder & Dobroth, 1987). For example, you are more likely to agree with your acquaintances, and they are more likely to agree with each other, about whether you are talkative than about whether you tend to worry and ruminate. This finding holds true even when the people who judge you are strangers and have observed you for only a few minutes (Funder & Colvin, 1988; see also Watson, 1989) or even less (Carney et al., 2007). In general, a trait like extraversion, which is reflected by overt behaviors such as high energy and friendliness, is easier to judge than a trait like emotional stability, which is reflected by anxieties, worries, and other mental states that may not be visible on the outside (S. S. Russell & Zickar, 2005). And behaviors of other people are easier to rate than their beliefs and values (Paunonen & Kam, 2014). To find out about less visible, more internal traits like beliefs or tendencies to worry, self-reports (S-data; see Chapter 2) are more informative (Vazire, 2010).

GOOD INFORMATION

The final moderator of judgmental accuracy is the amount and kind of information on which the personality judgment is based.

Amount of Information

Despite findings about first impressions summarized earlier in this chapter, it still seems to be the case that more information is usually better, especially when judging certain traits. One study found that, while traits such as extraversion, conscientiousness, and intelligence could be judged with some degree of accuracy after only 5 seconds of observation, traits such as neuroticism (emotional instability), openness, and agreeableness needed several minutes at least (Carney et al., 2007). Another study found that people were more accurate in judging each other after interacting twice, compared to just once (Cochran et al., 2018). In a study that examined more extended acquaintanceship, participants were judged both by people who had known them for at least a year and by strangers who had viewed the participants only for about 5 minutes on a videotape. Personality judgments by the close acquaintances agreed much better with the participants’ self-judgments than did judgments by strangers (Funder & Colvin, 1988).

More information

A photo shows a headshot of psychologist Melinda Blackman.

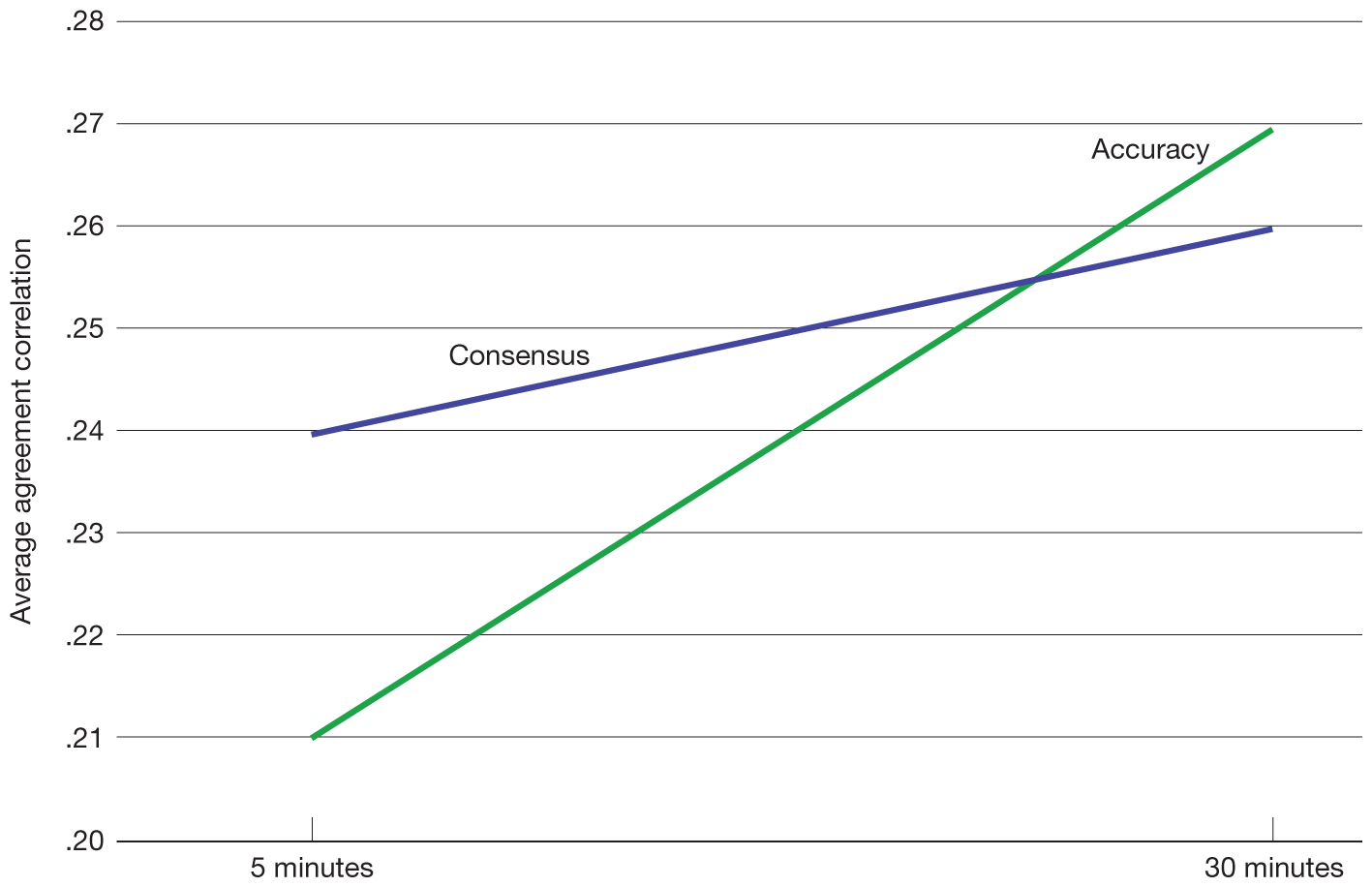

There is at least one interesting wrinkle to the effect of the quantity of information on accuracy. According to a study I did with former student (and current professor) Melinda Blackman (Figure 4.5), if judges are given more information, this will improve the agreement between their judgments and the target individual’s self-judgments, but it does not necessarily affect their agreement with each other (Blackman & Funder, 1998). Judges watched a series of videotapes of pairs of people having conversations. Some judges saw only one 5-minute tape, some saw two tapes (for a total of 10 minutes), and so on, up to those who saw six tapes for a total of 30 minutes of observation. Then they tried to describe the personality of one person they watched.

The results are illustrated in Figure 4.6. Consensus, or the agreement among judges, was almost as good at the beginning as it became by the end; it did not change significantly between the judges who watched 5 minutes versus those who watched 30 minutes of videotape. But accuracy, here indexed by the agreement between their descriptions and the targets’ own self-descriptions, did improve both noticeably and to a statistically significant degree.

More information

A line graph plots the average agreement correlation for consensus and accuracy over time. There are two lines shown: Consensus and Accuracy. The Consensus line starts at the coordinate (5 minutes, 0.24 agreement correlation) and ends at (30 minutes, 0.26 agreement correlation). The Accuracy line starts at the coordinate (5 minutes, 0.21 agreement correlation) and ends at (30 minutes, 0.27 agreement correlation).

Source: Blackman & Funder (1998), p. 177.

What caused this difference between consensus and accuracy? The cause seems to be that judges’ first impressions of their target agree with each other because they are based on superficial stereotypes and other potentially misleading cues. Because these stereotypes are shared among judges, the judges tend to agree with each other even if they are largely wrong. After observing the target for a period of time, however, judges begin to discard these stereotypes and see the person as the person really is. The result is not so much increased agreement among the judges as it is an improvement in the accuracy of what they agree on (for a related finding, see Biesanz et al., 2007).

Quality of Information

The amount of information available is important, but so is its quality. Common experience suggests that sometimes one can learn a lot about someone very quickly, and one can also “know” someone for a long time and learn very little. It depends on the situation and the information that it yields. For example, it can be far more informative to observe a person in a weak situation, in which different people do different things, than in a strong situation, in which social norms restrict what people do (Snyder & Ickes, 1985). This is why behavior at a party is more informative than behavior while riding a bus. At a party, extraverts and introverts act very differently, and it is not difficult to see who is which; on a bus, almost everybody just sits there. This is probably also why, according to some research, unstructured job interviews, where the interviewer and interviewee can talk about whatever comes to mind, are more valid for judging an applicant’s personality than are highly structured interviews where the questions are rigidly scripted in advance (Blackman, 2002b).

The quality of information that one gains in a more intimate relationship can promote more accurate judgment (Connelly & Ones, 2010, Study 2). This information can include the something extra that can be learned by observing people in a difficult or emotionally arousing situation. Watching how people act in an emergency or their response to a letter of acceptance or rejection from medical school, or even having a romantic encounter with someone, can reveal aspects of personality that you might not otherwise have suspected. One study showed that observing people in a stressful situation—for example, when they had to make a short speech while being video recorded—led to more accurate judgments of neuroticism than observations in a situation that was more relaxed (Hirschmüller et al., 2015). The best situation for judging someone’s personality is one that brings out the trait you want to judge. To evaluate a person’s approach toward work, the best thing to do is to observe the person working. To evaluate the person’s sociability, observations at a party would be more informative (Freeberg, 1969; Landy & Guion, 1970).

More information

A photo shows a headshot of psychologist Tera Letzring.

One innovative study evaluated the effect of quality of information using recorded interviews. Participants listened to people being asked either about their thoughts and feelings or about their daily activities and then tried to describe their personalities by rating a set of 100 traits. It turned out that listening to the thoughts-and-feelings interview “produced more ‘accurate’ social impressions, or at least impressions that were more in accord with speakers’ self-assessments prior to the interviews and with the assessments made by their close friends, than did [listening to] the behavioral . . . interviews” (Andersen, 1984, p. 294). In another study, psychologist Tera Letzring (Figure 4.7) found that people who met in an unstructured situation, where they could talk about whatever they wanted, made judgments of each other that were more accurate than judgments by those who met under circumstances that offered less room for idle chitchat (Letzring et al., 2006). Having a chance to talk is especially important for judging the ways in which people are “distinctive,” or different from each other (Letzring & Human, 2014) .

The accurate judgment of personality, then, depends on both the quantity and the quality of the information on which it is based. More information is generally better, but it is just as important for the information to be relevant to the traits that one is trying to judge.

The Realistic Accuracy Model

To bring sense and order to the wide range of moderators of accuracy, it is helpful to back up a step and ask how accurate personality judgment is possible in the first place. At least sometimes, people manage to accurately evaluate one or more aspects of the personalities of the people they know. How is this possible? One explanation is in terms of the Realistic Accuracy Model (RAM) (Funder, 1995).

THE FOUR STAGES OF RAM

In order to get from an attribute of an individual’s personality to an accurate judgment of that trait, four things must happen (Figure 4.8). First, the person being judged must do something relevant, that is, informative about the trait to be judged. Second, this information must be available to a judge. Third, this judge must detect this information. Fourth and finally, the judge must utilize this information correctly.

More information

A diagram depicts the realistic accuracy model. On the left is a profile image of a person looking to the right labeled “target”, with an arrow pointing to the right to a text box that reads “relevance”, with another arrow to another text box that reads “availability”, with another arrow to another text box that reads “detection”, with another arrow to another text box that reads “utilization” with another arrow that points to a profile image of a person labeled “judge” looking back at the target. An arrow that connects the target to the judge is labeled “accuracy”.

For example, consider attempting to judge someone’s degree of courage. This may not be possible unless a situation comes along that allows a courageous person to reveal this trait. But if the target of judgment encounters a burning building, rushes in, and saves the family inside, then the person has done something relevant. Next, this behavior must occur in a manner and place that make it possible for you, as the judge, to observe it. Someone might be doing something extremely courageous right now, right next door, but if you can’t see it, you may never know and never have a chance to assess accurately that person’s courage. But let’s say you happen by just as the target of judgment rescues the last member of the family from the flames. Now the judgment has passed the availability hurdle. That is still not enough: Perhaps you were distracted, or you are perceptually impaired (you broke your glasses in all the excitement), or for some other reason you failed to notice what happened. But if you did notice, then the judgment has passed the detection hurdle. Finally, you must accurately remember and correctly interpret the relevant, available information that you have detected. If you infer that this rescue means the target person rates high on the trait of courage, then you have passed the utilization stage and achieved, at last, an accurate judgment.

This model of accurate personality judgment has several implications. The first and most obvious implication is that accurate personality judgment is difficult. Notice how all four of the hurdles—relevance, availability, detection, and utilization—must be overcome before accurate judgment can be achieved. If the process fails at any step—the person in question never does something relevant, or does it out of sight of the judge, or the judge doesn’t notice, or the judge makes an incorrect interpretation—accurate personality judgment will fail.

The second implication is that the moderators of accuracy discussed earlier in this chapter—namely, good judge, good target, good trait, and good information—must be a result of something that happens at one or more of these four stages. For example, a good judge is someone who is good at detecting and utilizing behavioral information (McLarney-Vesotski et al., 2011). Good targets behave in accordance with their personality (relevance) in a wide range of situations (availability). A good trait is one that is displayed in a wide range of contexts (availability) and is easy to see (detection). Similarly, knowing someone for a long time in a wide range of situations (good information) can enhance the range of behaviors a judge sees (availability) and the odds that the judge will begin to notice patterns that emerge (detection).

IMPROVING ACCURACY

A third implication of this model might be the most important of all. According to RAM, the accuracy of personality judgment can be improved in four ways. Traditionally, efforts to improve accuracy have focused on attempts to get judges to think better, to use good logic and avoid inferential errors. These efforts are worthwhile, but they address only one stage—namely, utilization—out of the four stages of accurate personality judgment. Improvement could be sought at the other stages as well (Blanch-Hartigan & Cummings, 2021; Funder, 2003).

For example, consider the consequences of being known as a “touchy” person: People are more cautious or restrained when such a person is around. They avoid discussing certain topics and doing certain things whenever that person is present. As a result, the touchy person’s judgment of these acquaintances will become stymied at the relevance stage—that is, relevant behaviors that otherwise might have been performed in the person’s presence will be suppressed, along with the ability to judge these acquaintances accurately. A boss who blows up at bad news will lead employees to hide their mistakes, thus interfering with the availability of relevant information. As a result, the boss will be clueless about the employees’ actual performance and abilities and maybe even about how well the company is doing.

The situation in which a judgment is made can also affect its accuracy. Meeting someone under tense or distracting circumstances is likely to interfere with the detection of otherwise relevant and available information, again causing accurate judgment to be stymied. People on job interviews or first dates may not always be the most accurate judges of their interviewers or dates.

So maybe you can become a better judge of personality by attending to relevant cues. But it can involve more than that. You could elicit cues by asking questions, steering the conversation, or acting in such a way as to get the person to reveal what you want to know (Pick & Neuberg, 2022). Probably even better, you could also try to create an interpersonal environment where other people can be themselves and feel free to let you know what is really going on. It may be difficult to avoid situations where tensions and other distractions cause you to miss what is right in front of you. But it might be worth bearing in mind that your judgment in such situations may not be completely reliable, and to try to remember to calm down and be attentive to the other person as well as to your own thoughts, feelings, and goals.

Glossary

- constructivism

- The philosophical view that reality, as a concrete entity, does not exist and that only ideas (“constructions”) of reality exist.

- critical realism

- The philosophical view that the absence of perfect, infallible criteria for determining the truth does not imply that all interpretations of reality are equally valid; instead, one can use empirical evidence to determine which views of reality are more or less likely to be valid.

- convergent validation

- The process of assembling diverse pieces of information that converge on a common conclusion.

- interjudge agreement

- The degree to which two or more people making judgments about the same person provide the same description of that person’s personality.

- behavioral prediction

- The degree to which a judgment or measurement can predict the behavior of the person in question.

- predictive validity

- The degree to which one measure can be used to predict another.

- moderator variable

- A variable that affects the relationship between two other variables.

- judgability

- The extent to which an individual’s personality can be judged accurately by others.

Endnotes

- Also sometimes in politics, where “alternative facts” battle with objective truth.Return to reference 8

- An intriguing topic for future research concerns the appearance-changing software commonly available on video platforms. If you use the “enhance appearance” option in an online interview, will you be more likely to get the job?Return to reference 9

- In other words, sensitive judges are good-hearted.Return to reference 10

- The exact term used in the study was “everyday sadism.” Really, every day?Return to reference 11

- It is reasonable to wonder whether this can go too far. A person who is rigid and inflexible might be judged easily but would not be well adjusted. But remember that “behavioral consistency” means maintaining one’s individual distinctiveness, not acting the same way in all situations.Return to reference 12

- As we shall see in Chapter 16, the reverse pattern of erratic and unpredictable behavior and emotions is a hallmark of the very serious syndrome called borderline personality disorder.Return to reference 13