TYPOLOGICAL APPROACHES TO PERSONALITY

Over the years of successfully applying the three trait approaches, some psychologists have occasionally expressed misgivings about the whole enterprise. What if important differences between people are not just quantitative but qualitative? The trait approach typically assumes that all people can be characterized on a common scale. You might score high on extraversion and I might score low, but at least we are on the same scale. But what if some differences between people are matters not of degree but of kind? If your extraversion is fundamentally different from my shyness, then to summarize this difference by comparing our extraversion scores might be a little like comparing apples to oranges by giving both of them scores in “appleness” and concluding that oranges score lower.

Evaluating Typologies

Of course, it is one thing to raise doubts like these and quite another to say what the essential types of people really are. To typify all individuals, one must “carve nature at its joints” (as Plato reportedly said), by finding the exact dividing lines that distinguish one type of person from another. The further challenge is to show that these divisions are not just a matter of degree, that different types of people are qualitatively, rather than quantitatively, distinct. Repeated attempts did not achieve notable success over the years, leading one reviewer to summarize the literature in the following manner:

Muhammad Ali was reputed to offer this typology: People come in four types, the pomegranate (hard on the outside, hard on the inside), the walnut (hard-soft), the prune (soft-hard), and the grape (soft-soft). As typologies go, it’s not bad—certainly there is no empirical reason to think it any worse than those we may be tempted to take more seriously. (Mendelsohn et al., 1982, p. 1169)

Nonetheless, interest in typological conceptions of personality revived a bit (Kagan, 1994; Robins et al., 1998) after psychologist Avshalom Caspi (1998) reported some surprising progress: Across seven different studies with diverse participants all over the world, three types showed up again and again. One of the types is the well-adjusted person, who is adaptable, flexible, resourceful, and interpersonally successful. Then there are two maladjusted types: Maladjusted overcontrolling people are too uptight for their own good, denying pleasure needlessly, and being difficult to deal with on an interpersonal level. Maladjusted undercontrolling people have the opposite problems of being too impulsive, prone to be involved in activities such as crime and unsafe sex, and tending to wreak general havoc on other people and themselves. This is an interesting typology because it suggests that there is one way to be well adjusted but two ways to have psychological problems.

The types received wide attention by researchers and were found repeatedly in samples of participants in North America and Europe (Alessandri et al., 2014; Asendorpf & van Aken, 1999; Asendorpf et al., 2001). One analysis showed that people classified into a particular type were likely to belong to the same type four years later (Specht et al., 2014). But older people were less likely to belong to the undercontrolled type and more likely to belong to the well-adjusted or (as these investigators called it) “resilient” type than younger people.

Other work limits these conclusions in an important way. When thinking about personality types, one should keep two questions in mind. First, are different types of people, as identified by the typological approach, qualitatively and not just quantitatively different from each other? That is, are they different from each other in ways that conventional trait measurements cannot capture? The possibility that this is the case—namely, the apples-versus-oranges issue—is a big part of the reason psychologists viewed personality types as potentially important. However, the answer to this question turned out to be a pretty solid no. Knowing a person’s personality type adds little or nothing to the ability to predict behavior or life outcomes, beyond what can be done using the traits that define the type (Costa et al., 2002; McCrae et al., 2006).

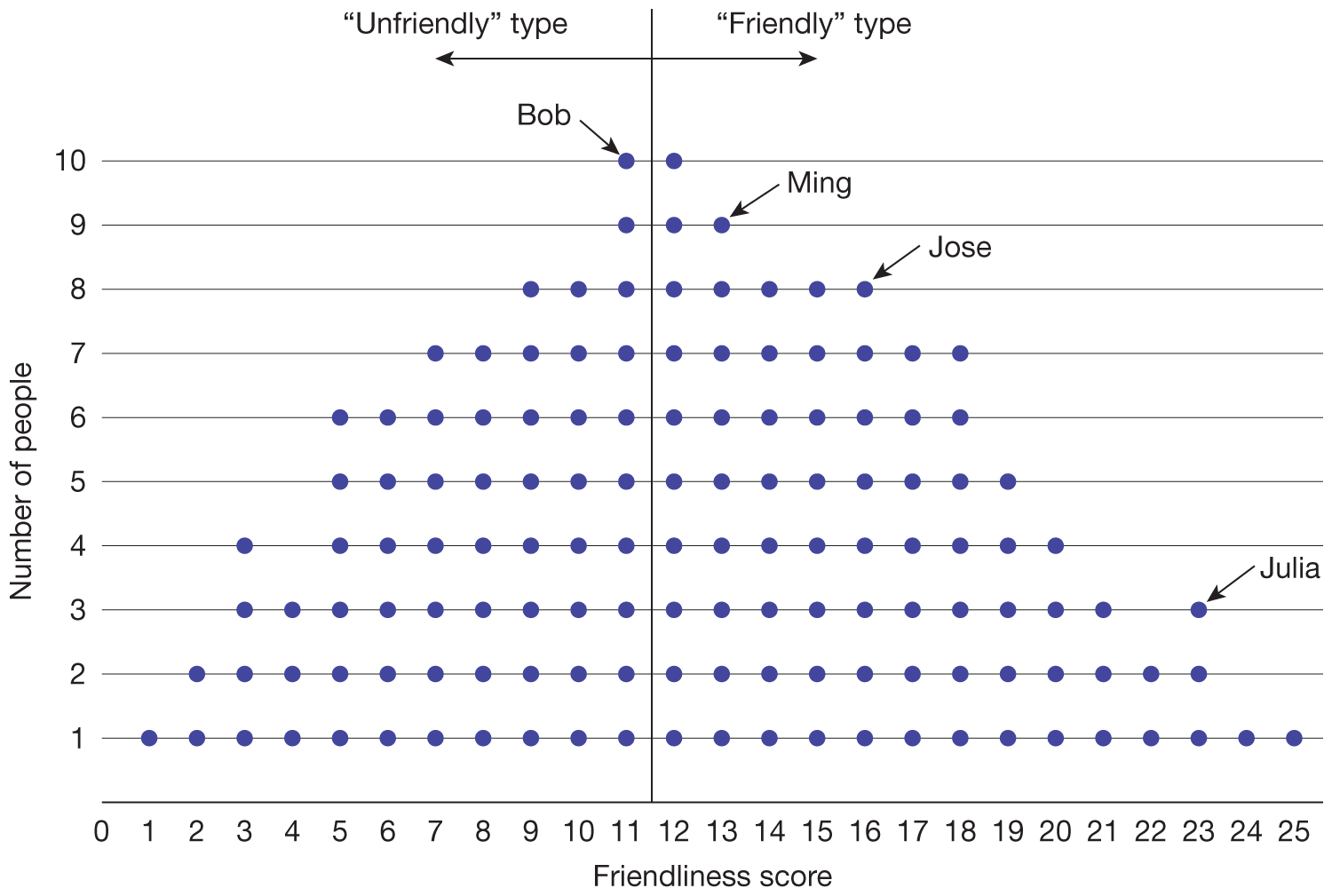

A second important limitation of personality types is more technical. Typically, the type a person is categorized to belong to is determined by a cutoff score. For example, imagine a 25-item test of friendliness in which different people earn scores anywhere between 0 and 25. Scores on almost every measure of anything turn out to be “normally distributed,” which simply means that, as in Figure 5.9, most people score toward the middle and fewer score extremely high or low. In other words, on most things, most people are pretty average. Now imagine, as is sometimes done, a psychologist wanted to call everybody who scored 12 or above as “Friendly” and everybody who scored 11 or below “Unfriendly.” This would be a typological approach, and potentially very misleading, because notice that Bob (who scored 11) and Ming (who scored 13) are categorized as being different types because they fall on different sides of the line, but Jose (who scored 16) and Julia (who scored 23) are categorized as the same type because they are on the same side of the line. But Jose and Julia’s scores are much further apart than Bob and Ming’s! This is actually a pretty common problem with typological measures, because measures with a “bimodal distribution” where most scores are either very high or very low, with few in the middle, are quite rare.

More information

A graph depicts friendliness scores. The horizontal axis is labeled “friendliness scores” and ranges from 1 to 25 in increments of 1. A vertical line is drawn from the horizontal axis at 11.5 and the values to its left are labeled, unfriendly type and the values to its right are labeled, friendly type. The vertical axis is labeled, number of people and it ranges from 1 to 10, in increments of 1. The graph infers the data in the following format: Number of people: Unfriendly type, friendly type. 1: 1-11, 12-25; 2: 2-11, 12-23; 3: 3-11, 12-21, 23 (Julia); 4: 3, 5-11, 12-20; 5: 5-11, 12-19; 6: 5-11, 12-18; 7: 7-11, 12-18; 8: 9-11, 12-16 (Jose); 9: 11, 12-13 (Ming); and 10: 11 (Bob), 12.

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator

One particular measure of personality types deserves consideration here, if for no other reason than because it is so popular. The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI; Myers & McCaulley, 1985) is taken by millions of people every year in workplaces, schools, counseling centers, and management workshops (Pittinger, 1993). And not for free. The MBTI is a big business with certified trainers and a network of marketers selling it as an ideal guide for career guidance and self-development. It’s very possible you have already encountered it yourself.

In case you haven’t, here is what it is like. The MBTI presents 166 items (only 95 of which are scored21) that force the test taker to make choices such as, “Which word in each pair appeals to you more? (a) Sociable (b) Detached.” The test is intended to measure which of two opposing tendencies, in four pairs, better characterize you. The four pairs are Extroversion22 (E) vs. Introversion (I), Sensing (S) vs. Intuition (N), Thinking (T) vs. Feeling (F), and Judgment (J) vs. Perception (P). For example, in the sample item above, choice (a) points toward Extroversion, and choice (b) points toward Introversion. The final result places you into one of 16 possible personality types, so you might be described as an ESTJ or and ISTJ or some other combination.

The test’s popularity stems, in part, from the seemingly rich and intriguing descriptions that it offers. An ESTJ, for example, is described as someone who reacts to the world rather than what is in the mind, focuses on what can be seen rather than on intuitions, is rational rather than emotional, and makes decisions by thinking and feeling, rather than by sensing and intuiting. The fact that many of the items on the MBTI are vague and difficult to answer seems to give the impression that it offers especially deep insight (Stein & Swan, 2019). Another reason for the test’s popularity is probably that there are no bad scores, something that the tests’ authors have been quite explicit about. Each type is a “different gift” (Myers, 1980), so nobody is ever unhappy with their test results. That’s wonderful, I suppose, but it does not make the MBTI very useful for selection or predicting life outcomes.

Perhaps the MBTI should carry a label, “for entertainment purposes only.”

The MBTI has been criticized on other grounds as well (for a summary see Pittinger, 1993; for updated evidence see Randall et al., 2017). Perhaps the most obvious problem is the same one that was described a few paragraphs ago and illustrated in Figure 5.9. The scores on the various scales of the MBTI are distributed normally, not bimodally, which means that two people both classified as E could be more different from each other than two people who are classified as E and I. A second problem is that although MBTI types are described as fundamental aspects of personality, the measurement is not reliable, in the sense described in Chapter 3. Specifically, if you were to be categorized as one type today, and you take the test again in five weeks, there is about a 50 percent chance you will be categorized as a different type, especially if you are in a different mood (Howes & Carskadon, 1979). Finally, the whole theory of using types for occupational guidance assumes that different MBTI types follow, persist in, or succeed in different lines of work. Yet there is no evidence this is so (Pittinger, 1993). For example, the ESTJ type is sometimes described as well suited for the teaching profession, but about 12 percent of the population are ESTJs, as are about 12 percent of all teachers!

So perhaps the MBTI should carry a label, “for entertainment purposes only.” Because, indeed, many people seem to find learning their MBTI types to be enjoyable. Then again, many people enjoy reading their horoscopes.

Uses of Personality Types

As we have now seen, there are many reasons to be skeptical of the typological approach to personality in general and the MBTI in particular. Still, a further question remains: Is it at all useful to think about people in terms of personality types? Despite everything, the answer to this question may still be yes (Asendorpf, 2002; Costa et al., 2002). Each personality type serves as a summary of how a person stands on a large number of traits. The adjusted, overcontrolled, and undercontrolled patterns are rich portraits that make it easy to think about how the traits within each type tend to be found together and how they interact. In the same way, thinking of people in terms of whether they are “military types,” “rebellious student types,” or “hassled suburban soccer mom types” brings to mind an array of traits in each case that would be cumbersome, though not impossible, to summarize in terms of ratings on each dimension. Advertisers and political consultants, in particular, often design their campaigns to appeal to specific types of people. For this reason, it has been suggested that types may be useful in the way they summarize “many traits in a single label” (Costa et al., 2002, p. 573) and make it easier to think about psychological dynamics. Even though types may not add much for conventional psychometric measurement and prediction, they may still be useful for education and applications such as advertising.

Endnotes

- Nobody seems to know why; the manual does not explain why almost half the items on the test are ignored (Sipps et al., 1985).Return to reference 21

- This spelling of extraversion is unusual in psychology, but it is not wrong.Return to reference 22