SOCIOLOGY’S FAMILY TREE

Great thinkers have been trying to understand the world and our place in it since the beginning of time. Some have done this by developing theories: abstract propositions about how things are, as well as how they should be. Sometimes we also refer to theories as “approaches,” “schools of thought,” “paradigms,” or “perspectives.” Social theories, then, are guiding principles or abstract models that attempt to explain and predict the social world.

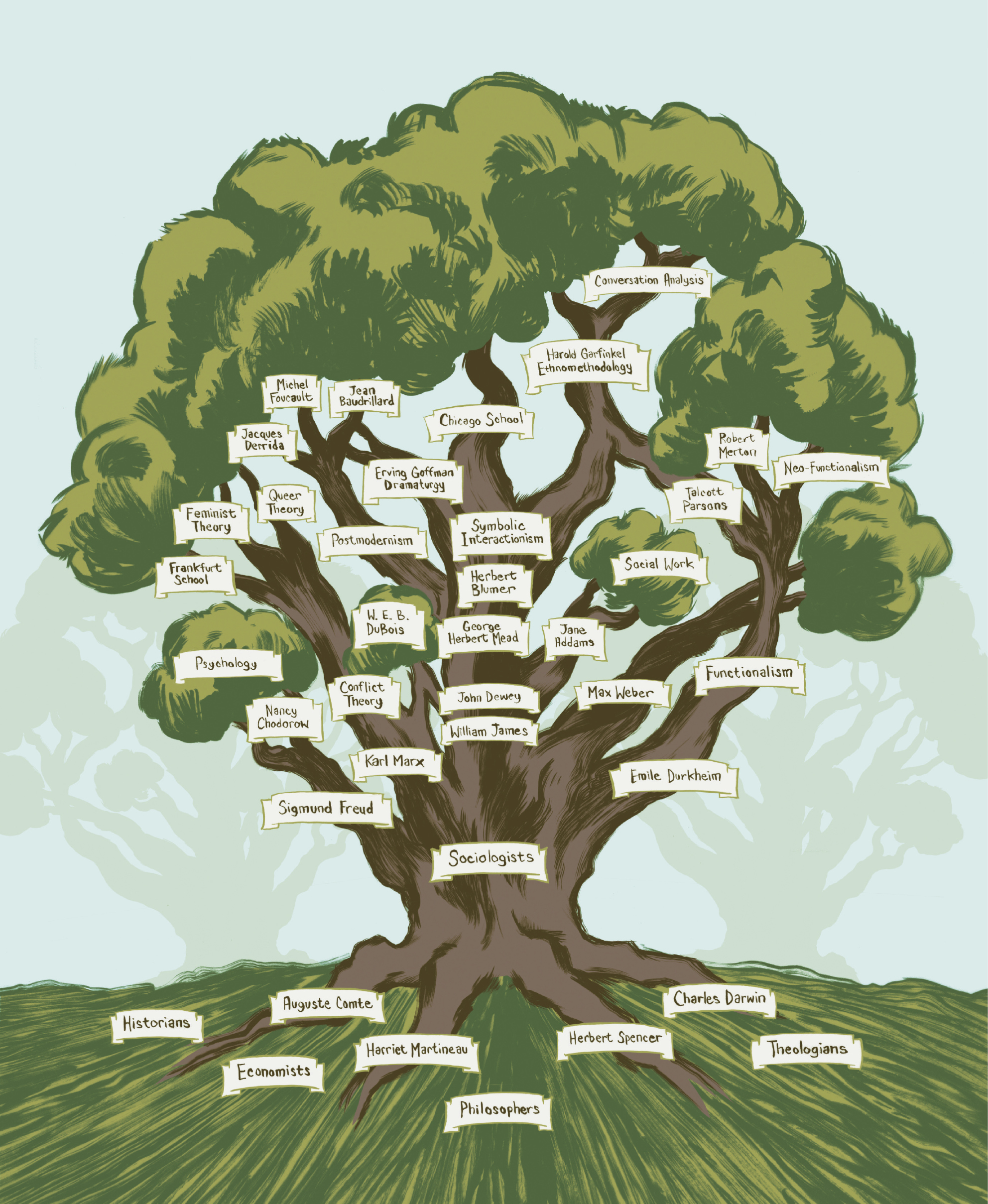

As we embark on the discussion of theory, it may be useful to think of sociology as having a “family tree” (page 17) made up of real people who were living in a particular time and place and who were related along various intertwining lines to other members of the same larger family tree. First, we will examine sociology’s early historical roots. Then, as we follow the growth of the discipline, we will identify its major branches and trace the relationships among their offshoots and the other “limbs” that make up the entire family tree. Finally, we will examine some of the newest theoretical approaches and members of the family tree and consider the possible future of sociological theory.

Sociology’s Roots

The earliest Western social theorists focused on establishing society as an appropriate object of scientific scrutiny, which was itself a revolutionary concept. These early theorists were not sociologists (since the discipline didn’t yet exist) but rather people from a variety of backgrounds—philosophers, theologians, economists, historians, journalists—who were trying to look at society in a new way. In doing so, they laid the groundwork not only for the discipline as a whole but also for the different schools of thought that are still shaping sociology today.

AUGUSTE COMTE (1798–1857)

was the first to provide a program for the scientific study of society, or a “social physics,” as he labeled it. Comte, a French scientist, developed a theory of the progress of human thinking from its early theological and metaphysical stages toward a final “positive,” or scientific, stage. Positivism seeks to identify laws that describe the behavior of a particular reality, such as the laws of mathematics and physics, in which people gain knowledge of the world directly through their senses. Having grown up in the aftermath of the French Revolution and its lingering political instability, Comte felt that society needed positivist guidance toward both social progress and social order. After studying at an elite science and technology college, where he was introduced to the newly discovered scientific method, he began to imagine a way of applying the methodology to social affairs. His ideas, featured in (1842), became the foundation of a scientific discipline that would describe the laws of social phenomena and help control social life; he called it “sociology.”

Although Comte is remembered today mainly for coining the term, he played a significant role in the development of sociology as a discipline. His efforts to distinguish appropriate methods and topics for sociologists provided the kernel of a discipline. Other social thinkers advanced his work: Harriet Martineau and Herbert Spencer in England and Émile Durkheim in France.

HARRIET MARTINEAU (1802–1876)

was born in England to progressive parents who made sure their daughter was well educated. She became a journalist and political economist, proclaiming views that were radical for her time—she endorsed labor unions, the abolition of slavery, and women’s suffrage.

In 1835, Martineau traveled to the United States to judge the new democracy on its own terms rather than by European standards. But she was disappointed: By condoning slavery and denying full citizenship rights to women and Black people, the American experiment was, in her eyes, flawed and hypocritical. She wrote two books describing her observations, Society in America (1837) and Retrospect of Western Travel (1838), both critical of American leadership and culture. By holding the United States to its own publicly stated democratic standards, rather than seeing the country from an ethnocentric British perspective, she was a precursor to the naturalistic sociologists who would establish the discipline in America. In 1853, Martineau made perhaps her most important contribution to sociology: She translated Comte’s Introduction to Positive Philosophy into English, thus making his ideas accessible in England and America.

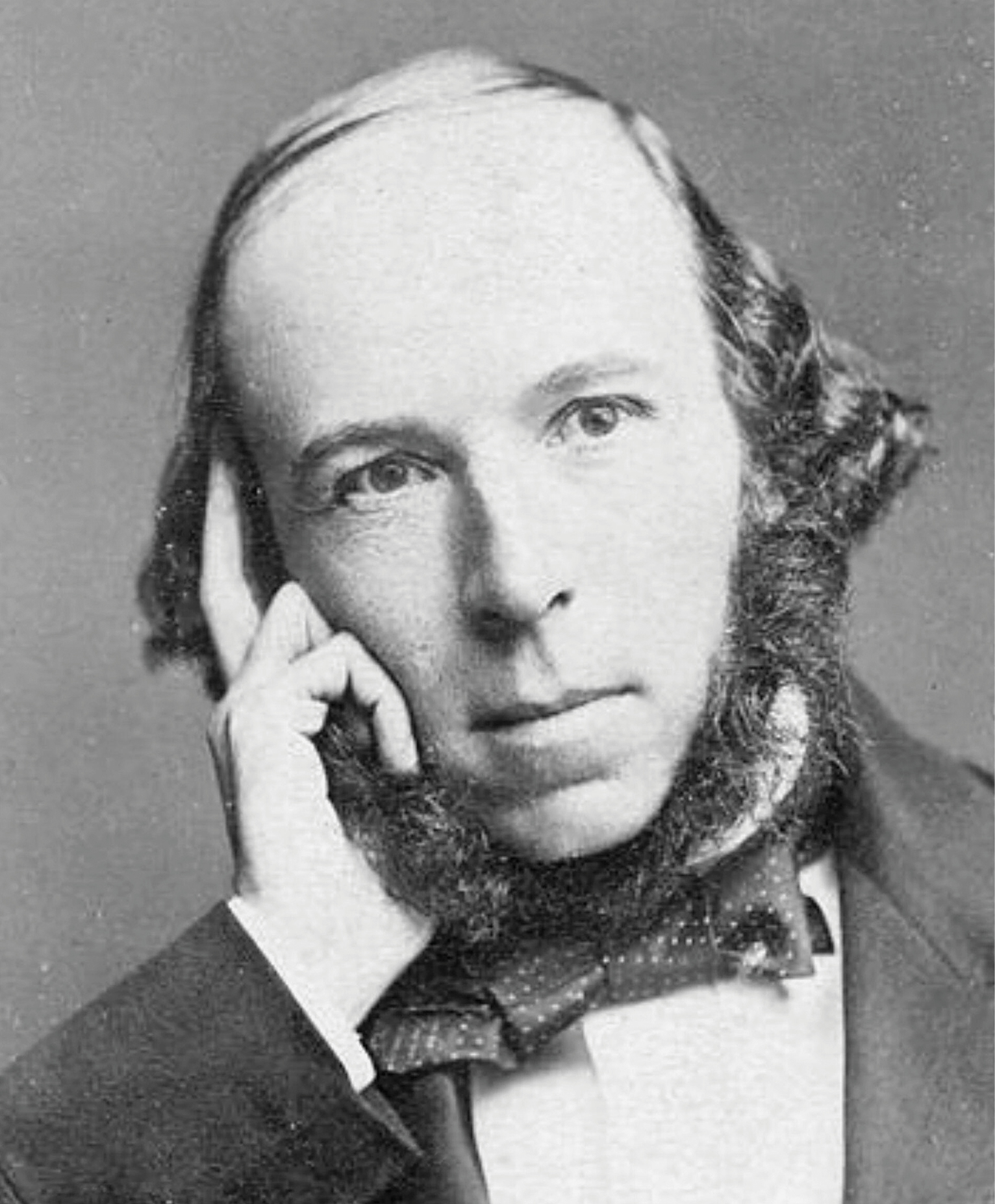

HERBERT SPENCER (1820–1903)

was primarily responsible for the establishment of sociology in Britain and America. Although Spencer did not receive academic training, he grew up in a highly individualistic family and was encouraged to think and learn on his own. His interests leaned heavily toward physical science and, instead of attending college, Spencer chose to become a railway engineer. When railway work dried up, he turned to journalism and eventually worked for a major periodical in London. There he became acquainted with leading English academics and began to publish his own thoughts in book form.

In 1862, Spencer drew up a list of what he called “first principles” (in a book by that name), and near the top of the list was the notion of evolution driven by natural selection. Charles Darwin is the best-known proponent of the theory, but the idea of evolution was in wide circulation before Darwin made it famous. Spencer proposed that societies, like biological organisms, evolve through time by adapting to changing conditions, with less successful adaptations falling by the wayside. He coined the phrase “survival of the fittest,” and his social philosophy is sometimes known as social Darwinism. In the late 1800s, Spencer’s work, including The Study of Sociology (1873) and The Principles of Sociology (1897), was virtually synonymous with sociology in the English-speaking world. The scope and volume of his writing served to announce sociology as a serious discipline and laid the groundwork for the next generation of theorists, whose observations of large-scale social change would bring a new viewpoint to social theory.

Glossary

- THEORIES

- abstract propositions that explain the social world and make predictions about the future

- PARADIGM

- a set of assumptions, theories, and perspectives that makes up a way of understanding social reality

- POSITIVISM

- the theory that sense perceptions are the only valid source of knowledge