❮❮

For a full discussion of meta-analysis, see Chapter 14, pp. 444–447.

In order to base your beliefs on empirical evidence rather than on experience, intuition, or authority, you will, of course, need to read about that research. But where do you find it and how will you know if the sources you found are high quality?

Psychological scientists usually publish their research in three kinds of sources. Most often, research results are published as articles in scholarly journals. In addition, psychologists may describe their research in single chapters within edited books, and some researchers also write full-length scholarly books.

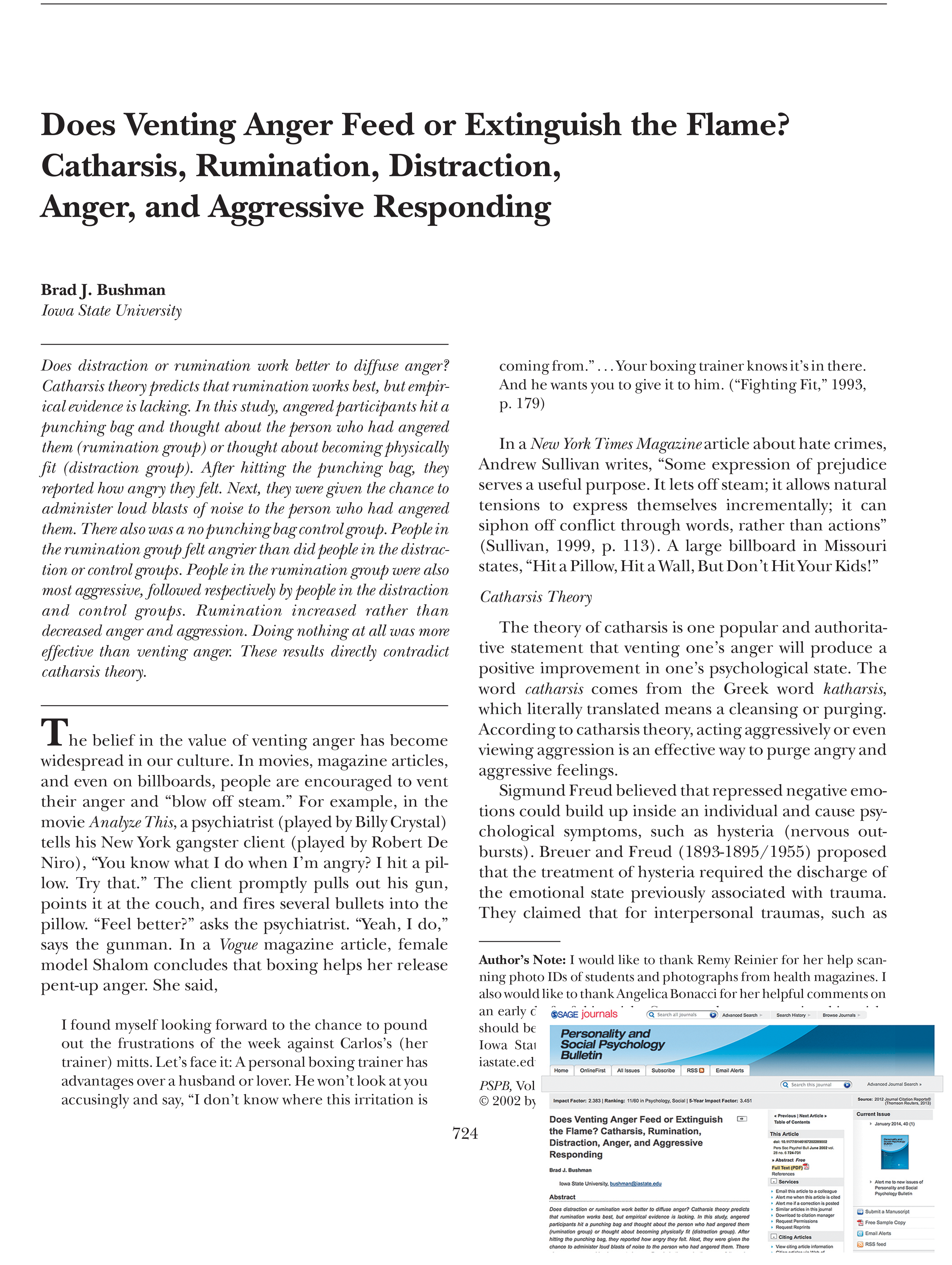

Scientific journals come out monthly or quarterly, as magazines do. Unlike popular magazines, however, scientific journals do not have glossy, colorful covers or advertisements. For example, the study by Bushman (2002) described earlier was published in the scientific journal Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

Journal articles are written for an audience of other psychological scientists and psychology students. They can be either empirical articles or review articles. Empirical journal articles report, for the first time, the results of an (empirical) research study. Empirical articles contain details about the study’s method, the statistical tests used, and the results of the study. Figure 2.13 is an example of an empirical journal article.

STRAIGHT FROM THE SOURCE

Figure 2.13

Bushman’s empirical article on catharsis.

The first page is shown here, as it appeared in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. The inset shows how the article appears in an online search in that journal. Clicking “Full Text pdf” takes you to the article shown. (Source: Bushman, 2002.)

❮❮

For a full discussion of meta-analysis, see Chapter 14, pp. 444–447.

Review journal articles summarize and integrate all the published studies that have been done in one research area. A review article by Alina Nazareth and her colleagues (2019), for example, summarized 266 studies on human sex differences in navigation skills (such as estimating distance or pointing to the right direction). Sometimes a review article uses a quantitative technique called meta-analysis, which combines the results of many studies and gives a number that summarizes the magnitude, or the effect size, of a relationship. In the Nazareth review (2019), the authors computed the average effect size across all 266 studies. Meta-analysis is valued by psychologists because it weighs each study proportionately and does not allow cherry-picking particular studies.

Before being published in a journal, both empirical articles and review articles must be peer-reviewed (see Chapter 1). Both types are considered the most prestigious forms of publication, in part because of this peer review process.

One way to get an overview of a body of research is to read a scholarly book or an edited book. Compared with scholars in other disciplines, such as art history or English, psychologists do not write many full-length scientific books for an audience of other psychologists. It is more common to contribute a chapter to an edited book. An edited book is a collection of chapters on a common topic, each chapter of which is written by a different contributor. For example, the edited book The Handbook of Emotion Regulation (2014) contains more than 30 chapters, all written by different researchers. Edited book chapters are a good place to find a summary of a set of research a particular psychologist has done. Chapters are not peer-reviewed as rigorously as empirical journal articles or review articles. However, the editor of the book is careful to invite only experts—researchers who are intimately familiar with the empirical evidence on a topic—to write the chapters. The audience is usually other psychologists and psychology students (Figure 2.14).

Figure 2.14

The variety of scientific sources.

You can read about research in empirical journal articles, review journal articles, edited books, and full-length books.

Your university library’s reference staff can be extremely helpful in teaching you how to find appropriate scientific sources. Working on your own, you can also use tools such as PsycINFO and Google Scholar to conduct searches.

PsycINFO is a comprehensive tool for sorting through the vast amount of psychological research. Doing a search in PsycINFO is like using Google, but PsycINFO searches only sources in psychology.

PsycINFO has many advantages. It can show you all the articles written by a single author (e.g., “Brad Bushman”) or under a single keyword (e.g., “autism”). It tells you whether each source was peer-reviewed. The tool “Cited by” links to other articles that have cited each target article, and the tool “References” links to the other articles each target article used. That means if you’ve found a great article for your project in PsycINFO, the “Cited by” and “References” lists can be helpful for finding more papers just like it. One disadvantage to PsycINFO is that your college or university library must subscribe; the general public cannot use it.

To use PsycINFO, simply try it yourself or ask a reference librarian to show you the basic steps. One challenge for students is translating curiosity into the correct search terms. Don’t get discouraged if your initial search terms are not working. It takes a few rounds to learn the terms that researchers use to study your question. Table 2.2 presents some strategies for turning your questions into successful searches.

Tips for Turning Your Question into a Successful Database Search

|

|

|

The free tool Google Scholar works like the regular Google search engine, except the search results will all be in the form of empirical journal articles and scholarly books. In addition, by visiting the user profile for a particular scientist, you can see all of that research team’s publications.

One disadvantage of Google Scholar is that it doesn’t let you limit your search terms to specific fields (such as the abstract or title). In addition, it doesn’t categorize the articles it finds—for example, as peer-reviewed or not—whereas PsycINFO does. And because Google Scholar contains articles from all scholarly disciplines, it may take more time for you to sort through the results.

Just because you find a scientific journal article through an online search doesn’t mean you should use it. Most journals are legitimate: Their research was conducted appropriately, their editors facilitate true peer review, and scientists in the community recognize and trust them (Bergstrom & West, 2017).

Other journals are called “predatory.” Their names sound legitimate (e.g., The Journal of Science or Psychiatry and Mental Disorders), but they publish almost any submission they receive, even fatally flawed studies (Bohannon, 2013). They exist to make money by charging fees to scientists who want to publish their work.

How can you judge journal quality? Your professors and librarians can tell you the names of legitimate journals in psychology—so ask them! You can use an online tool such as Cabell’s blacklist of predatory journals. Another rough guide is whether the journal is listed in Journal Citation Reports, which calculates “impact factor.” This metric tells you how often, on average, papers in that journal have been cited. The impact factor of the highly respected Psychological Science is 6.1, which means that on average its papers are cited 6 times. Impact factor isn’t perfect (Chambers, 2017); it cannot tell you whether an article’s science is actually sound. But if a journal has an impact factor of at least 1.0, it is more likely to be legitimate (Bergstrom & West, 2017).

While you are enrolled in college, you have access to almost any scientific article, through either your own library or interlibrary loan. Once you leave the university, you will learn that some articles are paywalled, or subscription only. Other articles are open access, or available for free to the general public. Open-access publication of science supports Merton’s norm of communality—science should be available for everyone, including the taxpaying public. If you’re blocked by a paywall, try the scientist’s personal website or the repositories PsyArXiv or PubMed Central (keeping in mind that some manuscripts on PsyArXiv have not yet passed through peer review).

Once you have found an empirical journal article or chapter, then what? You might wonder how to go about reading the material. Some journal articles contain an array of statistical symbols and unfamiliar terminology. Even the titles of journal articles and chapters can be intimidating. How is a student supposed to read empirical articles? It helps to know what you will find in an article and to read with a purpose.

Most empirical journal articles (those that report the results of a study for the first time) are written in a standard format, as recommended by the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA, 2020). They usually include certain sections in the same order: abstract, introduction, Method, Results, Discussion, and References. Each section contains a specific kind of information. (For more on empirical journal articles, see Presenting Results: APA-Style Reports at the end of this book.)

Abstract. The abstract is a concise summary of the article. It briefly describes the study’s hypotheses, method, and major results. When you are collecting articles for a project, the abstracts can help you quickly decide whether each article describes the kind of research you are looking for, or whether you should move on to the next article.

Introduction. The introduction is the first section of regular text, and the first paragraphs typically explain the topic of the study. The middle paragraphs lay out the background for the research. What theory is being tested? What have past studies found? Why is the present study important? Pay special attention to the final paragraph, which states the specific research questions, goals, or hypotheses for the current study.

Method. The Method section explains in detail how the researchers conducted their study. It usually contains subsections such as Participants, Materials, Procedure, and Apparatus. An ideal Method section gives enough detail that if you wanted to repeat the study, you could do so without having to ask the authors any questions.

Results. The Results section describes the quantitative and, as relevant, qualitative results of the study, including the statistical tests the authors used to analyze the data. It usually provides tables and figures that summarize key results. Although you may not understand all the statistics used in the article, you might still be able to understand the basic findings by looking at the tables and figures.

Discussion. The opening paragraph of the Discussion section generally summarizes the study’s research question and methods and indicates how well the results of the study supported the hypotheses. Next, the authors usually discuss the study’s importance: Perhaps their hypothesis was new, or the method they used was a creative and unusual way to test a familiar hypothesis, or the participants were unlike others who had been studied before. In addition, the authors may discuss alternative explanations for their data and pose interesting questions raised by the research.

References. The References section contains a full bibliographic listing of all the sources the authors cited in writing their article, enabling interested readers to locate these studies. When you are conducting a literature search, reference lists are excellent places to look for additional articles on a given topic. Once you find one relevant article, the reference list for that article will contain a treasure trove of related work.

Here’s some surprising advice: Don’t read every word of every article, from beginning to end. Instead, read with a purpose. In most cases, this means asking two questions as you read: (1) What is the argument? (2) What is the evidence to support the argument? The obvious first step toward answering these questions is to read the abstract, which provides an overview of the study. What should you read next?

Empirical articles are stories from the trenches of the theory-data cycle (see Figure 1.5 in Chapter 1). Therefore, an empirical article reports on data that are generated to test a hypothesis, and the hypothesis is framed as a test of a particular theory. After reading the abstract, try skipping to the end of the introduction, where you’ll find the primary goals and hypotheses of the study. After reading the goals and hypotheses, you can read the rest of the introduction to learn more about the theory that the hypotheses are testing. Another place to find the argument of the paper is the first paragraph of the Discussion section, where most authors summarize the key results and state how well the results supported their hypotheses.

Once you have a sense of what the argument is, look for the evidence. In an empirical article, the evidence is contained in the Method and Results sections. What did the researchers do, and what results did they find? How well do these results support their argument (i.e., their hypotheses)?

While empirical journal articles use predetermined headings such as Method, Results, and Discussion, authors of chapters and review articles create their own headings for the topic. You can use these headings to get an overview before you start reading in detail.

As you read these sources, again ask: What is the argument? What is the evidence? The argument will be the purpose of the chapter or review article—the author’s stance on the issue. In a review article or chapter, the argument often presents an entire theory (whereas an empirical journal article usually tests only one part of a theory). Here are some examples of arguments you might find:

The evidence is the research that the author reviews. What research has been done? How strong are the results? What do we still need to know? With practice, you will learn to categorize what you read as argument or evidence, and you will be able to evaluate how well the evidence supports the argument.

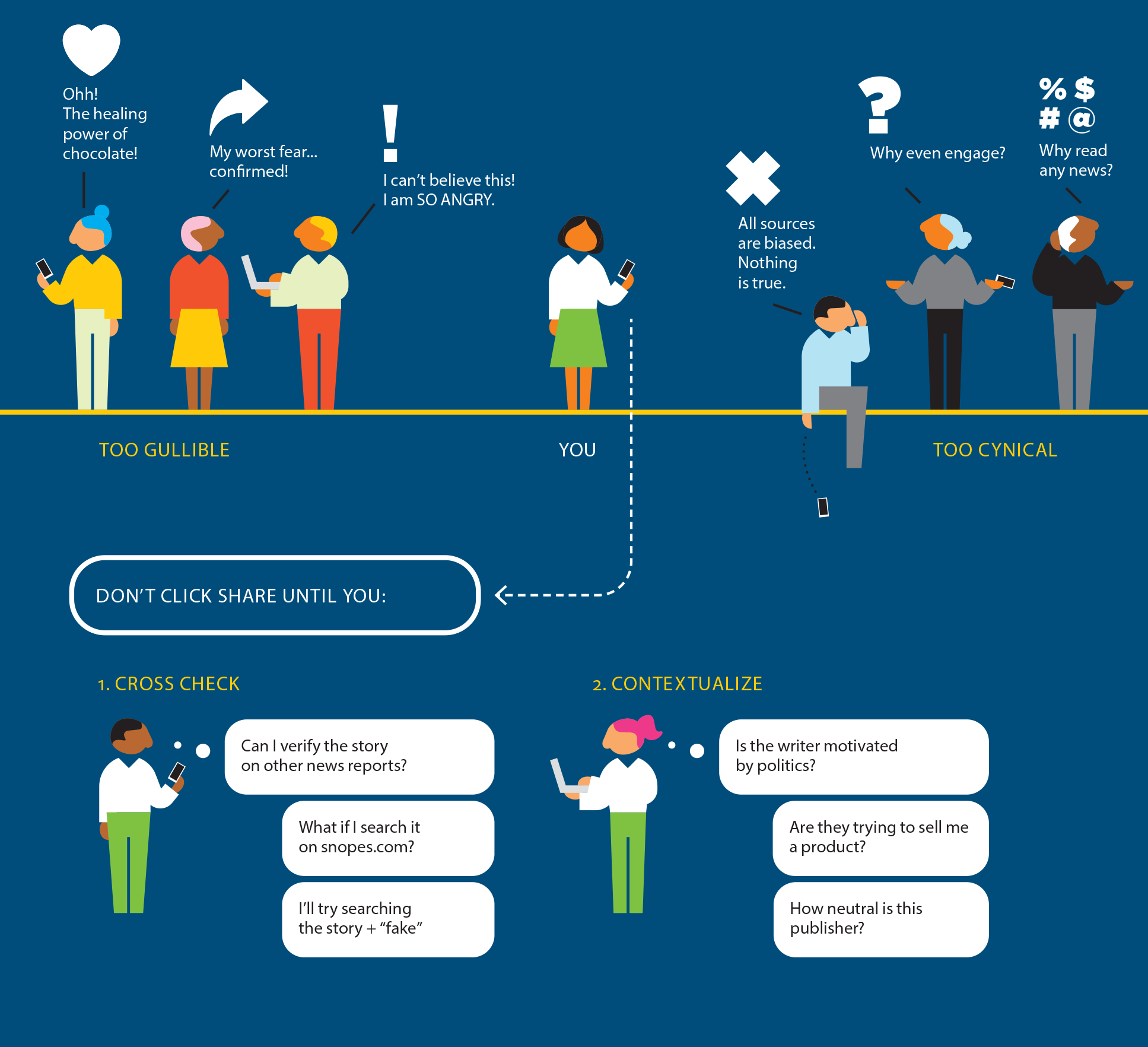

Reading about research in its original form is the best way to get a thorough, accurate, and peer-reviewed report of scientific evidence. But you’ll encounter descriptions of psychology research in less scholarly places, too. Journalists can provide good overviews of psychological research, but you should choose and read your sources carefully and be vigilant for disinformation (Figure 2.15).

Figure 2.15

What you see online may not accurately represent reality.

Journalists play an important role in telling the public about findings in psychological science. Psychological research may be covered in specialized outlets such as Psychology Today and the Hidden Brain podcast, which are devoted exclusively to covering social science research for a popular audience. Research also makes its way to wider news feeds and online newspapers. Table 2.3 contrasts scientific journals and journalism coverage.

Scholarly and Popular Articles About Research Serve Different Goals and Audiences

|

Scholarly articles (journals) |

Popular articles (journalism) |

|

|

Example Sources |

Psychological Science, Child Development, Journal of Experimental Psychology |

New York Times, Vox, CNN, Time, Scientific American, Wall Street Journal |

|

Purpose |

Report the results of research after it has been peer-reviewed Discuss ongoing research in detail |

Summarize research that may be of interest to the general public |

|

Authors |

Scholars, always named, and often identified by the institution at which they work |

Journalists, who are often unnamed |

|

Audience |

Scholars and researchers within a specific field of study |

The general public |

|

Language |

Highly specialized and/or technical, and often includes professional jargon not easily understood by the general public |

Can be understood by most people |

|

Sources |

Always include sources and full Reference list |

Typically do not include footnotes or a list of sources, though they may mention the original researchers and include links to their published journal articles |

Source: Adapted from Butler University Libraries and Center for Academic Technology (https://libguides.butler.edu/c.php?g=117303&p=1940118 ).

Most science journalists do an excellent job. They read the original research, interview multiple experts, and fact-check. As you read about science in popular sources, it’s worth thinking critically about two issues. First, journalists may select a more sensational, clickable story while overlooking its flaws. Second, even when studies are conducted well, journalists may not describe them accurately.

How Good Is the Study Behind the Story? When journalists report on a study, have they chosen research that has been conducted rigorously, that tests an important question, and that has been peer-reviewed? Or have they chosen a study simply because it is sensational or moralistic?

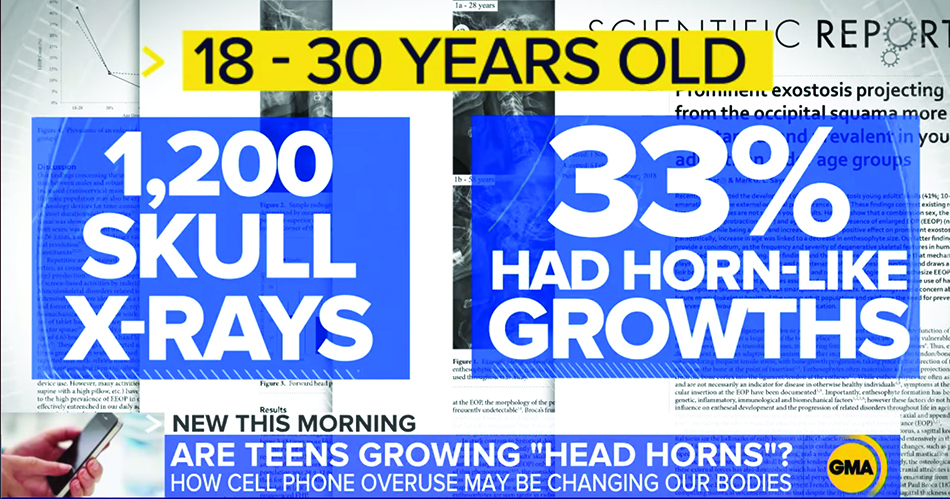

For example, one summer the headlines read, “Horns are growing on young people’s skulls. Phone use is to blame, research suggests” (Figure 2.16). This headline shocked readers and listeners and was covered by multiple news outlets. The “horns” in question referred to bone growths of 10mm or more that were visible via X-ray at the back of people’s skulls. The researchers reported that 41% of participants ages 18 to 30 had one of these enlargements on their skulls. The journal publication behind this journalism had been peer-reviewed, usually a sign of the study’s quality.

Figure 2.16

Journalists may not cover the best research.

This sensational news report was based on a single research study that was later widely criticized by other researchers and journalists. Although the news report prominently displays some of the numerical values from the study, the study’s method was not adequate to determine that cell phone use was “changing our bodies.”

As the “horn” headlines went viral, other journalists began writing stories about the study’s flaws. These critical reviews revealed that the study did not actually measure phone use. Therefore, it could not establish a link between phone use and bone growth. In addition, the X-rays that the study analyzed were exclusively from people who had visited a chiropractor for neck pain. Therefore, it was impossible to know if the reported rates of bone growth would apply to the general population. Finally, the researchers failed to disclose a conflict of interest—at least one author was a chiropractor who sells a pillow designed to improve people’s posture.

Two days after the first headline about the horns, the headlines began to change for the better. One read, “Smartphones aren’t making millennials sprout horns. Here’s how to spot a bad study.” Fortunately, in this particular case, you could have obtained a full picture by reading laterally—that is, finding other stories on the same topic written from different perspectives. As you progress in this book, you will learn to read journalism more critically and even spot flawed research yourself.

Is the Story Accurate? Even when journalists report on reliable, well-conducted research, they don’t always get the story right. Sometimes a journalist does not have the scientific training, motivation, or time before deadline to understand the original science very well. Maybe the journalist sands down the details to make it more accessible to a general audience. And sometimes a journalist wraps up the details of a study with a more dramatic headline than the research can support. For example, in the bone growth study, the original researchers did not use the term “horns.” That term was added by a journalist, perhaps to make the story more clickable.

When you read popular media coverage of psychology research, use your skills as a consumer of information to read the content critically—especially if the news is something you wanted to hear. Use PsycINFO or Google Scholar to locate the original empirical article to see how well the journalist summarized the work.

The specific skill of critically reading science journalism can be generalized to other online content. Did an eagle swoop down and fly off with a human baby? Did a bird poop on Vladimir Putin during a press conference? Was someone paid $3,500 to protest Donald Trump at a rally? Is the @RogueNASA Twitter account really written by a NASA employee? While it’s humorous to learn that the eagle and Putin videos are fake, other disinformation may have a more sobering impact on civic engagement.

Disinformation (“fake news”) is not simply mainstream journalism that you don’t believe or agree with. Instead, disinformation is “the deliberate creation and sharing of information known to be false” (Wardle, 2017). It takes many forms. Those who spread disinformation include hate groups who have cloaked false, racist stories in websites disguised to look real (Daniels, 2009). They include false foreign social media accounts aimed at suppressing African American votes in the United States (DiResta et al., 2018; Shane & Frenkel, 2018). People cannot always tell when news is fake; in fact, one poll found that the majority of Americans from both political parties believed fake news headlines they had seen (Silverman & Singer-Vine, 2016). Disinformation matters. It has made some people disengage from voting. It has made others act drastically: In 2016, after reading unfounded conspiracy stories, a man fired a rifle into a pizza restaurant he read was a sex-trafficking site.

Motives of Disinformation. People spread deliberately false information for several reasons (Wardle, 2017). Propaganda, passion, and politics motivate some of it: Disinformation can drive votes and enhance political support. Provocation motivates people who want to “punk” others into emotional reactions. Profit is a motive too: False scientific claims about salt lamps, herbal supplements, or crystals may accompany a shopping website. There’s also the chance that it’s parody—sites like The Onion create false stories only to make us laugh.

Types of Disinformation. Some disinformation is completely false. Other disinformation is more subtle: It might attribute false quotes to real people or use a real quote in a false context. Photos and videos can be especially provocative and convincing. Disinformation might involve manipulating photos or videos (as in the eagle and Putin stories) or pasting real images into false contexts.

Read Critically but Not Cynically. We need to gather information to fulfill our obligations as citizens. How can we avoid falling for disinformation without giving up and disengaging? It helps to slow down and cross-check. If a social media share makes you feel fearful, angry, or vindicated, track down the source. What’s the real context? Is the source neutral or biased? Is it a hoax? Infographic Figure 2.17 presents ways to verify stories you might be tempted to believe.

1. See pp. 39–41. 2. See p. 44. 3. See pp. 41–42. 4. See pp. 46–48.

Be Information Literate, Not Gullible or Cynical

If a social media share makes you feel fearful, angry, or vindicated, track down the source. What’s the real context? Is the source neutral or biased? Is it a hoax?