CASE STUDY: ACCRA, GHANA

The surf rolls in under the half moon, stars shining dimly in the hazy sky. It’s Friday evening and Next Door, a festive club at a resort on the outskirts of Accra, is filled with people listening and dancing to the sounds of the Silver Wings band playing highlife. This musical style was given its name around 1920 when local melodies were first arranged for urban Ghanaian ballroom orchestras who entertained upper-class audiences. It became popular worldwide through concerts and sound recordings.3 At the same time, highlife achieved a unique place within Ghanaian consciousness. To quote one Ghanaian listener at Next Door: “Highlife—it’s our national music.”

Much of the history of Accra echoes through the strains of highlife, which unites several streams of the Ghanaian musical past. In highlife one can hear traces of sea chanteys and folk songs carried by sailors of many nationalities to the coast of West Africa; the instruments and sounds of military bands introduced by European military and colonial forces over the centuries in the area known as the Gold Coast; and piano music and church hymns widely dispersed among the educated elite by the late nineteenth century. Highlife fell somewhat out of fashion in the last decades of the twentieth century as competition from other West African popular musics increased, but it has continued to transform itself, to be widely distributed through recordings, and to be performed in Accra for engagements, weddings, and christenings, at nightclubs, and on the radio. Highlife is so central to Ghanaian life that Silver Wings is just one of several groups recruited and supported by the Ghanaian military to play at official functions and public concerts. With trumpets, guitar, bass, keyboard, two drummers, and several singers, Silver Wings performs highlife classics, most with texts in Twi, the indigenous language of the Akan peoples who constitute about half the population of Ghana.

MULTICULTURAL ACCRA

The location of Accra and its role as a port have over the centuries made it a magnet for cultural exchange, bringing together a wide array of people and their musical traditions. The forced flow of musical influences between the Gold Coast, Europe, and the New World during the centuries of the slave trade was followed by the region’s incorporation into the British Empire in the late nineteenth century. Global connections were further ensured by the early introduction of English, which remains Ghana’s official language, since no single indigenous language is spoken in all areas. In 1877 Accra became the capital of the Gold Coast, a British colony, and it remained the capital when the Gold Coast became the independent country of Ghana in 1957. Accra in the early twenty-first century is a sprawling city of nearly three million people, its streets a chaotic mix of carts, cars, taxis, buses, and ramshackle minibuses known as tro-tros, all producing a symphony of honking horns blended with the ubiquitous sounds of Ghanaian radio stations.

Koo Nimo (Daniel Amponsah) is one of Ghana’s most revered musicians, shown here (on right holding guitar) with his Adadam Agofomma (Roots Ensemble) from Kumasi, Ghana. Koo Nimo plays a form of acoustic guitar highlife known as palmwine music, named after a drink made from fermented palm-tree sap. The musician on the far left plays an idiophone called the prem-presiwa, or rumba box.

Modern Accra was settled by the Ga people in the fifteenth century. The Portuguese arrived shortly thereafter, launched the gold trade, and introduced Christianity. The arrival of Dutch, Danish, and English forces followed, and many of the trading posts and forts they constructed to protect the gold trade were refitted for the slave trade. Migration from inland Ga communities further swelled the population along the coast.4 The establishment of Accra as capital of the Gold Coast in the late nineteenth century intensified the city’s political and economic importance and attracted further waves of immigrants, as did Accra’s subsequent role as the capital of independent Ghana.

The presence of the Ga ethnic community has long lent Accra much of its distinctive cuisine, including the long strips of fried plantains sold by street vendors, and much of its traditional music. The Ga people celebrate the Homowo Festival annually, an occasion for performance of well-known Ga dances, accompanied by drumming. Homowo (“Mocking Hunger”) marks the Ga community’s triumph over famine with a successful harvest, commemorating the period during which the Ga people migrated to the area from regions farther east in what is present-day Nigeria. The seven-day Homowo Festival, celebrated in August or September throughout Ga neighborhoods in Accra, culminates in the Great Durbar, a lively musical celebration attended by all chiefs, subchiefs, and a broad cross-section of the community. The Homowo Festival is also celebrated by Ghanaians living outside of Ghana, in locales ranging from Miami to Philadelphia to London.5

Ga chiefs, strewing corn and accompanied by horn blowers, process through the streets of Jamestown, Accra, on the final day of the Homowo Festival.

Various ethnic festivals dot the Ghanaian calendar and are celebrated publicly; elaborate funerals are also celebrated by most ethnic communities in Accra. Driving through the neighborhoods of the city, one frequently passes crowds observing wakes outdoors; women and men sit in chairs on opposite sides of the road, listening to live or recorded music while eating and drinking. Individuals come together not only to commemorate the dead, but also to celebrate the community of which the deceased was a member. An elaborate funeral, with the full display of music and food not only marks an individual’s passing, but also provides evidence of his or her contribution during life.

Accra at the beginning of the twenty-first century extended over approximately 200 square kilometers along the central Ghanaian coast.

Providing a funeral can tax the resources of many families, especially those of struggling immigrants. For this reason, the Ewe people, who until the early decades of the twentieth century lived mainly to the east of Accra in the rural Volta region and who migrated to the capital for economic reasons, have banded together with others from their hometowns in funeral associations. One such group, Milo Mianoewo (“Love Your Neighbor”), was founded in 1972 by Ewe people who came to Accra from Dzodze, a large town near the Togo border. Several hundred members of the association pay dues and meet once a month to socialize and make music. When a member of the association dies, the society buys the coffin and covers all expenses for the burial, supplying food, drink, and music for the wake. Should a member die in Accra, the association transports the body to the hometown and observes the funeral—a three-day affair. At the monthly meetings of the association, drinks and snacks are served and individuals join in performing traditional Ewe songs and dances.

In Listening Guide 21 (see p. 74), we hear the members of the funeral association perform agbadza (“ahg-bahd-ZHA”), a dance performed at Ewe social gatherings and at funerals. Said to have derived from a dance performed by fighters returned from war, over the years agbadza became a popular social dance, today performed by both men and women.6 The lyrics of agbadza songs change frequently; new texts often allude to migration or current political and social issues.7 In addition to the alternation of a solo singer and chorus in call-and-response format, agbadza involves a number of instruments, including idiophones and membranophones. The agbadza rhythms are for many listeners the most familiar aspects of the music and are frequently borrowed for use with new texts in contexts ranging from hymns to popular songs.

1:39 |

Date of recording: January 11, 2004 Performers: Members of the Dzodzemidodzi Association, Milo Mianoewo Form: Excerpt from a polyphonic and polyrhythmic form Function: Used for social events and funerals |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• Rattles (axatse) supplying a 2 + 2 + 2 + 3 + 3 pattern, or timeline, operating as a central rhythmic reference for the drummers, singers, and dancers; clapping follows rattles

• High-pitched stick drums (sogo and kidi), which fill out the timeline and respond to the master drummers

• Two lower-pitched hand-and-stick master drums (atsimevu), whose part is much more varied and tends to converse both with the higher stick drums and with individual dancers

• Call-and-response between lead singers and chorus

|

DESCRIPTION |

0:00 |

Four distinct parts—rattles (axatse), stick drums (sogo and kidi), hand-and-stick drums (atsimevu), and vocal call-and-response—combine throughout. Near the beginning of this recording, the lead male singer calls in an improvisatory manner and tends to overlap the choral responses. The distance of the microphone from the singers and the dense polyphonic texture made it impossible to transcribe the text. |

0:16 |

Lead male singer is heard most clearly here. |

0:54 |

Male lead singer is joined by the female lead singer, and the vocal part becomes more fixed. |

1:10 |

The two high-pitched stick drums can be heard especially well here, as the microphone moves closer to the drums. |

1:34 |

Fade-out. |

Just as agbadza rhythms are widely associated with the Ewe people, different drums and their music are linked to other Ghanaian ethnic groups. Perhaps best known is the atumpan (“ah-toom-PAHN”), a drum associated with the Akan people, which includes a number of subgroups, including the Asante, Fante, and Akyem. Atumpan are the main instruments used for ceremonies by Asante chiefs and for state occasions by the Asante king. These large, goblet-shaped drums have a single drumhead attached by wire to a flexible round frame made of bamboo and secured to the body of the drum by laces tied to protruding tuning pegs. Atumpan are produced in pairs of “male” and female” drums but are played by a single drummer, a practice said to reflect the interdependence of men and women in Akan society, which is matrilineal in descent and inheritance customs. The atumpan are played as part of the Asante king’s orchestra, called the Fontomfrom, as well as part of the Adowa orchestra performing dances for Asante funeral celebrations.

Members of the funeral association Milo Mianoewo wear traditional garments made of java cloth to their monthly meeting. Men shake the axatse, calabash rattles covered with mesh net threaded with beads. Two seated men play the sogo (rear) and kidi (foreground) drums. In the right-hand image, women sing, dance, and clap the agbadza.

In addition to their prominence in Akan social and ceremonial life, the atumpan are also talking drums that were used in the past for communication. The atumpan can produce tones on several different pitch levels, enabling the drum to replicate the inflections of the tonal Akan language, Twi. Listening Guide 22 (see p. 76) demonstrates the ability of the atumpan to speak, presenting a short narrative about the history of the Denkyira state, a powerful kingdom which ruled over many Akan peoples until its defeat by the Asante at the end of the seventeenth century. The text in Listening Guide 22 resembles the form used for a traditional ritual, first explaining its purpose and then naming powerful beings—both traditional deities and historical figures.

James Acheampong constructs Akan drums of cordia (tweneboa) wood, leather, cowrie shells, cow hide, brass, and other local materials in his workshop at the Centre for National Culture in Kumasi, Ghana. A pair of recently completed atumpan drums are in the foreground, with two donno, double-headed drums with laces connecting the two drumheads, resting on the table behind them. Several of James Acheampong’s drums are on permanent display in the lobby of the National Theatre in Accra.

0:58 |

Date of recording: 1992–93 Performers: Elizabeth Kumi, appellant; Joseph Manu, drummer Form: Appellation (naming) text in Twi language Function: To glorify performer and his/her lineage; to demonstrate drum language |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• Ability of the drum to talk, performing both new text and historical drum language

• Manner in which the tonal contours of the spoken text are replicated by the subsequent drum phrase

|

STRUCTURE AND TEXT |

TRANSLATION |

DESCRIPTION |

0:00 |

Me ma mo atena ase, Nana ne me mpaninfoo |

Greetings to those present. I welcome you, Nana, and his elders, |

|

Owura dwamtenani, Enanom ne agyanom, ne anuanom a yeahyia ha, yegye me asona. |

Mr. Chairman, mothers, fathers, and brethren here gathered. The response to my greeting is asona. |

||

Saa twenekasa yi fa Odeefuo Boa Amponsem, Denkyira hene no. Odomankoma kyerema, ma no nko! |

This drum language is about Odeefuo Boa Amponsem, King of Denkyira. Creator’s drummer, let it go! |

||

0:27 |

Adawu, Adawu, Denkyira mene sono. Adawu, Adawu, Denkyira pentenprem, Omene sono, ma wo ho ne so. |

Adawu, Adawu, Denkyira is the devourer of the elephant. Adawu, Adawu, Denkyira the quicksand, Devourer of the elephant, come forth in thy light, show your glory! |

Drum language, glorifying King of Denkyira. |

Pentenprem, ma wo ho ne so, Ma wo ho ne so. Kronkron, kronkron, kronkron, Amponsem Koyirifa, ma wo ho ne so. Ako nana ma wo ho ne so. |

Quicksand, show your glory, Show your glory. Your holiness, holiness, holiness, Amponsem Koyrifa, show your glory. Grandson of the Parrot, show your glory. |

||

0:57 |

Fade-out. |

MUSIC IN GHANAIAN CHRISTIAN LIFE

A substantial amount of musicmaking in Accra occurs within the context of religious rituals. Although many traditional belief systems are still practiced, especially in the rural locales, using indigenous music in their devotional and healing activities, the entry of Christianity into coastal Ghana left a marked Christian influence in rural and urban areas. Throughout Accra, belief is prominently displayed in signs and billboards advertising the numerous churches that dot the city. Many shops carry Christian or biblical names, such as the By His Grace Chop Bar, the Jesus Dressmaking and Hair Dressing Center, and Faith Art Services.

Churches are located on virtually every block, and most support substantial musical activity. For instance, the large Evangelical Presbyterian Bethel Church in the New Town section of Accra holds two full services each Sunday morning. The first is trilingual, in Twi, Ewe, and English. The service incorporates a corresponding diversity of musical styles, featuring songs performed in Western harmony by the church’s youth choir accompanied by traditional drumming, hymns accompanied by an organ, and lively worship songs performed with the support of amplified bass guitar, synthesizer, and drum set. The music unites Western musical influences with Ewe rhythmic complexity, reflecting the widespread use of indigenous rhythms and melodies in Ghanaian choral music, both sacred and secular.8 The repertory ranges from new worship songs to traditional hymns sung in either the Twi or Ewe languages. Once a month, when everyone in the congregation marches forth from their pews to deposit a cash donation in one of seven boxes corresponding to the day of the week on which the individual was born, that month’s birthdays are announced and the congregation sings Happy Birthday in unison.

Many churches in Accra hold healing rituals that seek to cure illnesses through prayer and participation in musicmaking. Many of these rituals incorporate traditional indigenous healing practices.

One such group, The Kwabenya Prayer Camp of the Bethel Prayer Ministry International Church, holds daily rituals as well as “breaking sessions” to cure diseases; their newsletter invites everyone to “Bring the sick, barren, demon-possessed and people with all kinds of problems for healing and deliverance.” 9 Songs accompanied by instruments including synthesizer, guitar, and a drum set are the main venue through which healing is accomplished, and members of the congregation join their ministers in ecstatic speaking in tongues, followed by singing and dancing in the aisles. The Bethel Prayer Ministry, which has a congregation of more than 1,000, is also an international organization, with congregations located elsewhere in Africa, Europe, and the United States. Their activities bring us full circle, demonstrating once again the striking international reach of seemingly local traditions in Accra.

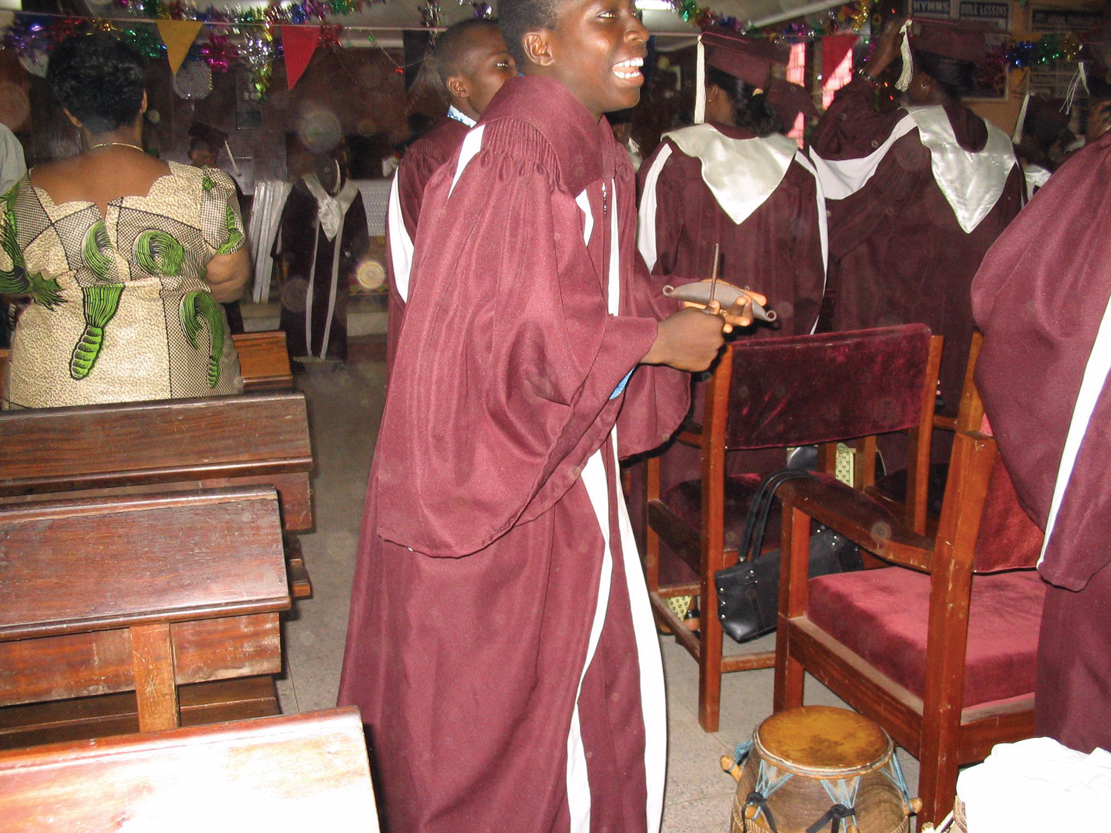

The Youth Choir of the Evangelical Presbyterian Bethel Church in Accra sings, accompanied by the rhythm of the atoke, a small handmade metal idiophone.

ACCRA’S GLOBAL CONNECTIONS

In Accra, the complex blend of local and international traditions emerges in all aspects of musical life and gives the city’s music a distinctive, cosmopolitan flavor. An example is the range of musics heard on Ghanaian radio: Listeners can tune into Radio Gold 90.5, which features foreign offerings; switch to Joy FM 99.7, which mixes local and foreign styles; or listen to popular Peace Radio 104.3, which often plays highlife recordings. Many Accra radio stations are streamed online as well. Among the explicitly local broadcasts is a music show in Ewe every Sunday to help the Ewe in Accra keep current on “what’s happening back home.”

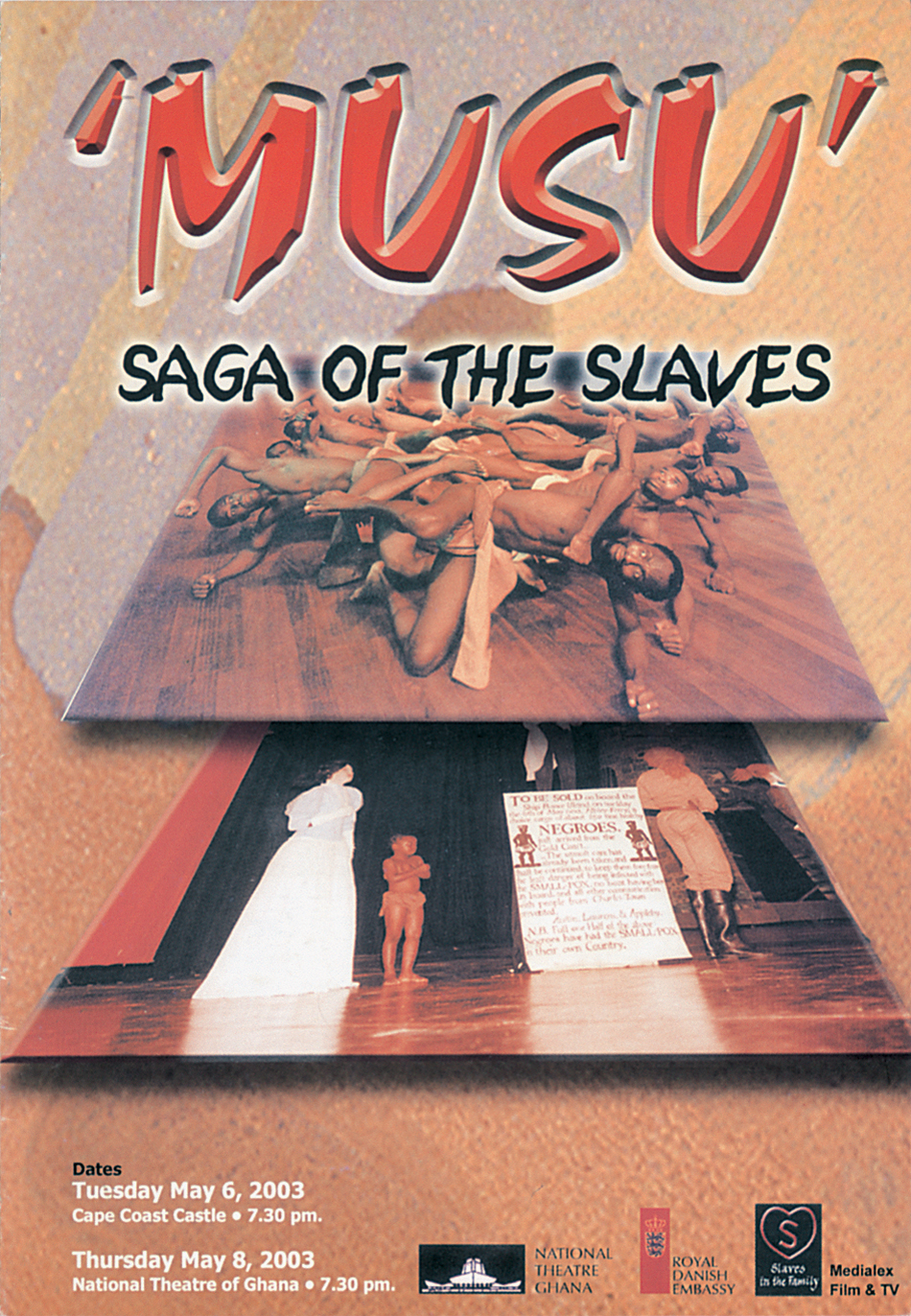

Since 1998, secondary-school students have participated in the Noyam (Ga for “Moving On”) African Dance Institute, a program of the National Dance Company of Ghana. The troupe has undertaken international and national tours to perform Musu (“Abomination”), a synthesis of poetry, dance, and music recounting the story of the Danish involvement in the Gold Coast slave trade starting in the late seventeenth century. The program for this event describes Musu as “an attempt to stimulate mankind to reflect on the whole issue of slavery worldwide.”

Like much of Africa, Accra continues to listen to cassettes, which have been displaced by new digital technologies in the United States, Canada, and most of Europe. Small kiosks at sites ranging from traditional marketplaces to modern supermarkets sell new and used cassettes, while shops in downtown Accra display recent CDs and DVDs, arranging recordings under a mix of familiar and novel rubrics. One finds bins for Reggae, Jazz/Country, and R&B/Hip Hop alongside a space for Locals/Gospel, an important Christian musical genre in Accra. One shelf, marked “Cools,” contains selections considered to be Cool Music, including various blues recordings and CDs by superstars such as Michael Jackson, Lionel Ritchie, and Elton John.

Accra’s role as Ghana’s capital extends into musical life; a number of musical ensembles reinforce national identity, helping to unite the many historically independent ethnic groups brought together as a nation less than fifty years ago and representing Ghana to the world. In addition to the National Symphony Orchestra, the thirty-member Pan-African Orchestra under the direction of Nana Danso Abiam performs concerts, issues recordings, and mounts tours abroad. The National Theatre houses both Abibigroma, the National Drama Company of Ghana, and the National Dance Company. Founded in 1962 by musicians from the University of Ghana, the National Dance Company merges traditional Ghanaian dances with contemporary dance styles; it performs both at home and abroad. In its mission to export Ghanaian culture, the National Dance Company of Ghana is, like the musical profile of the city it represents, at once local and global, achieving “a dramatic fusion of African and Contemporary Dance.”