TWO“HER POINT IS” The Art of Summarizing

IF IT IS TRUE, as we claim in this book, that to argue persuasively you need to be in dialogue with others, then summarizing others’ arguments is central to your arsenal of basic moves. Because writers who make strong claims need to map their claims relative to those of other people, it is important to know how to summarize effectively what those other people say. (We’re using the word “summarizing” here to refer to any information from others that you present in your own words, including that which you paraphrase.)

Many writers shy away from summarizing—perhaps because they don’t want to take the trouble to go back to the text in question and wrestle with what it says, or because they fear that devoting too much time to other people’s ideas will take away from their own. When assigned to write a response to an article, such writers might offer their own views on the article’s topic while hardly mentioning what the article itself argues or says. At the opposite extreme are those who do nothing but summarize. Lacking confidence, perhaps, in their own ideas, these writers so overload their texts with summaries of others’ ideas that their own voice gets lost. And since these summaries are not animated by the writers’ own interests, they often read like mere lists of things that X thinks or Y says—with no clear focus.

As a general rule, a good summary requires balancing what the original author is saying with the writer’s own focus. Generally speaking, a summary must at once be true to what the original author says while also emphasizing those aspects of what the author says that interest you, the writer. Striking this delicate balance can be tricky, since it means facing two ways at once: both outward (toward the author being summarized) and inward (toward yourself). Ultimately, it means being respectful of others but simultaneously structuring how you summarize them in light of your own text’s central argument.

ON THE ONE HAND, PUT YOURSELF IN THEIR SHOES

To write a really good summary, you must be able to suspend your own beliefs for a time and put yourself in the shoes of someone else. This means playing what the writing theorist Peter Elbow calls the “believing game,” in which you try to inhabit the worldview of those whose conversation you are joining—and whom you are perhaps even disagreeing with—and try to see their argument from their perspective. This ability to temporarily suspend one’s own convictions is a hallmark of good actors, who must convincingly “become” characters whom in real life they may detest. As a writer, when you play the believing game well, readers should not be able to tell whether you agree or disagree with the ideas you are summarizing.

If, as a writer, you cannot or will not suspend your own beliefs in this way, you are likely to produce summaries that are so obviously biased that they undermine your credibility with readers. Consider the following summary:

David Zinczenko’s article “Don’t Blame the Eater” is nothing more than an angry rant in which he accuses the fast-food companies of an evil conspiracy to make people fat. I disagree because these companies have to make money. . . .

If you review what Zinczenko actually says (pp. 199–202), you should immediately see that this summary amounts to an unfair distortion. While Zinczenko does argue that the practices of the fast-food industry have the effect of making people fat, his tone is never “angry,” and he never goes so far as to suggest that the fast-food industry conspires to make people fat with deliberately evil intent.

Another telltale sign of this writer’s failure to give Zinczenko a fair hearing is the hasty way he abandons the summary after only one sentence and rushes on to his own response. So eager is this writer to disagree that he not only caricatures what Zinczenko says but also gives the article a hasty, superficial reading. Granted, there are many writing situations in which, because of matters of proportion, a one- or two-sentence summary is precisely what you want. Indeed, as writing professor Karen Lunsford (whose own research focuses on argument theory) points out, it is standard in the natural and social sciences to summarize the work of others quickly, in one pithy sentence or phrase, as in the following example:

Several studies (Crackle, 2012; Pop, 2007; Snap, 2006) suggest that these policies are harmless; moreover, other studies (Dick, 2011; Harry, 2007; Tom, 2005) argue that they even have benefits.

But if your assignment is to respond in writing to a single author, like Zinczenko, you will need to tell your readers enough about the argument so they can assess its merits on their own, independent of you.

When summarizing something you’ve read, be sure to provide a rigorous and thoughtful summary of the author’s words, or you may fall prey to what we call “the closest cliché syndrome,” in which what gets summarized is not the view the author in question has actually expressed but a familiar cliché that the writer mistakes for the author’s view (sometimes because the writer believes it and mistakenly assumes the author must too). So, for example, Martin Luther King Jr.’s passionate defense of civil disobedience in “Letter from Birmingham Jail” might be summarized not as the defense of political protest that it actually is but as a plea for everyone to “just get along.” Similarly, Zinczenko’s critique of the fast-food industry might be summarized as a call for overweight people to take responsibility for their weight.

Whenever you enter into a conversation with others in your writing, then, it is extremely important that you go back to what those others have said, that you study it very closely, and that you not confuse it with something you already believe. Writers who fail to do this end up essentially conversing with imaginary others who are really only the products of their own biases and preconceptions.

ON THE OTHER HAND, KNOW WHERE YOU ARE GOING

Even as writing an effective summary requires you to temporarily adopt the worldview of another person, it does not mean ignoring your own view altogether. Paradoxically, at the same time that summarizing another text requires you to represent fairly what it says, it also requires that your own response exert a quiet influence. A good summary, in other words, has a focus or spin that allows the summary to fit with your own agenda while still being true to the text you are summarizing.

Thus if you are writing in response to the essay by Zinczenko, you should be able to see that an essay on the fast-food industry in general will call for a very different summary than will an essay on parenting, corporate regulation, or warning labels. If you want your essay to encompass all three topics, you’ll need to subordinate these three issues to one of Zinczenko’s general claims and then make sure this general claim directly sets up your own argument.

For example, suppose you want to argue that it is parents, not fast-food companies, who are to blame for children’s obesity. To set up this argument, you will probably want to compose a summary that highlights what Zinczenko says about the fast-food industry and parents. Consider this sample:

In his article “Don’t Blame the Eater,” David Zinczenko blames the fast-food industry for fueling today’s so-called obesity epidemic, not only by failing to provide adequate warning labels on its high-calorie foods but also by filling the nutritional void in children’s lives left by their overtaxed working parents. With many parents working long hours and unable to supervise what their children eat, Zinczenko claims, children today are easily victimized by the low-cost, calorie-laden foods that the fast-food chains are all too eager to supply. When he was a young boy, for instance, and his single mother was away at work, he ate at Taco Bell, McDonald’s, and other chains on a regular basis, and ended up overweight. Zinczenko’s hope is that with the new spate of lawsuits against the food industry, other children with working parents will have healthier choices available to them, and that they will not, like him, become obese.

In my view, however, it is the parents, and not the food chains, who are responsible for their children’s obesity. While it is true that many of today’s parents work long hours, there are still several things that parents can do to guarantee that their children eat healthy foods. . . .

The summary in the first paragraph succeeds because it points in two directions at once—both toward Zinczenko’s own text and toward the second paragraph, where the writer begins to establish her own argument. The opening sentence gives a sense of Zinczenko’s general argument (that the fast-food chains are to blame for obesity), including his two main supporting claims (about warning labels and parents), but it ends with an emphasis on the writer’s main concern: parental responsibility. In this way, the summary does justice to Zinczenko’s arguments while also setting up the ensuing critique.

This advice—to summarize authors in light of your own agenda—may seem painfully obvious. But writers often summarize a given author on one issue even though their text actually focuses on another. To avoid this problem, you need to make sure that your “they say” and “I say” are well matched. In fact, aligning what they say with what you say is a good thing to work on when revising what you’ve written.

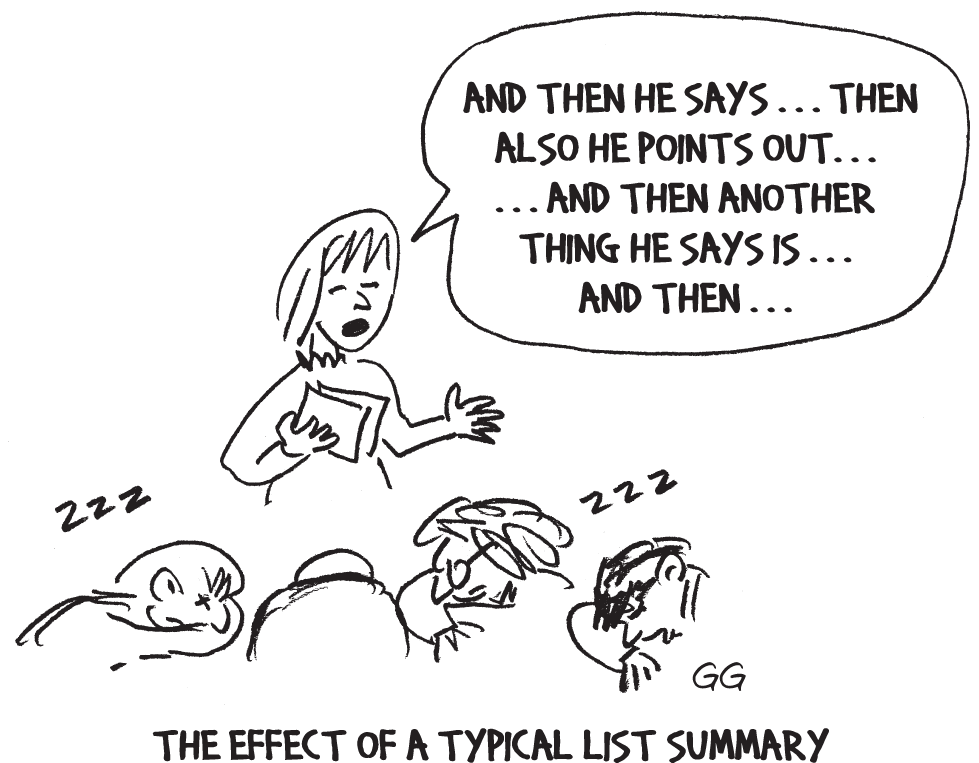

Often writers who summarize without regard to their own agenda fall prey to what might be called “list summaries,” summaries that simply inventory the original author’s various points but fail to focus those points around any larger overall claim. If you’ve ever heard a talk in which the points were connected only by words like “and then,” “also,” and “in addition,” you know how such lists can put listeners to sleep—as shown in the figure below. A typical list summary sounds like this:

The author says many different things about his subject. First he says . . . Then he makes the point that . . . In addition he says . . . And then he writes . . . Also he shows that . . . And then he says . . .

It may be boring list summaries like this that give summaries in general a bad name and even prompt some instructors to discourage their students from summarizing at all.

Not all lists are bad, however. A list can be an excellent way to organize material—but only if, instead of being a miscellaneous grab bag, it is organized around a larger argument that informs each item listed. Many well-written summaries, for instance, list various points made by an author, sometimes itemizing those points (“First, she argues . . . ,” “Second, she argues . . . ,” “Third . . .”), and sometimes even itemizing those points in bullet form.

Many well-written arguments are organized in a list format as well. In “The New Liberal Arts,” Sanford J. Ungar lists what he sees as seven common misperceptions that discourage college students from majoring in the liberal arts, the first of which begin:

Misperception No. 1: A liberal-arts degree is a luxury that most families can no longer afford. . . .

Misperception No. 2: College graduates are finding it harder to get good jobs with liberal-arts degrees. . . .

Misperception No. 3: The liberal arts are particularly irrelevant for low-income and first-generation college students. They, more than their more-affluent peers, must focus on something more practical and marketable.

SANFORD J. UNGAR, “The New Liberal Arts”

What makes Ungar’s list so effective, and makes it stand out in contrast to the type of disorganized lists our cartoon parodies, is that it has a clear, overarching goal: to defend the liberal arts. Had Ungar’s article lacked such a unifying agenda and instead been a miscellaneous grab bag, it almost assuredly would have lost its readers, who wouldn’t have known what to focus on or what the final “message” or “takeaway” should be.

In conclusion, writing a good summary means not just representing an author’s view accurately but doing so in a way that fits what you want to say, the larger point you want to make. On the one hand, it means playing Peter Elbow’s believing game and doing justice to the source; if the summary ignores or misrepresents the source, its bias and unfairness will show. On the other hand, even as it does justice to the source, a summary has to have a slant or spin that prepares the way for your own claims. Once a summary enters your text, you should think of it as joint property—reflecting not just the source you are summarizing but your own perspective or take on it as well.

SUMMARIZING SATIRICALLY

Thus far in this chapter we have argued that, as a general rule, good summaries require a balance between what someone else has said and your own interests as a writer. Now, however, we want to address one exception to this rule: the satiric summary, in which writers deliberately give their own spin to someone else’s argument in order to reveal a glaring shortcoming in it. Despite our previous comments that well-crafted summaries generally strike a balance between heeding what someone else has said and your own independent interests, the satiric mode can at times be a very effective form of critique because it lets the summarized argument condemn itself without overt editorializing by you, the writer.

One such satiric summary can be found in Sanford J. Ungar’s essay “The New Liberal Arts,” which we just mentioned. In his discussion of the “misperception,” as he sees it, that a liberal arts education is “particularly irrelevant for low-income and first-generation college students,” who “must focus on something more practical and marketable,” Ungar restates this view as “another way of saying, really, that the rich folks will do the important thinking, and the lower classes will simply carry out their ideas.” Few who would dissuade disadvantaged students from the liberal arts would actually state their position in this insulting way. But in taking their position to its logical conclusion, Ungar’s satire suggests that this is precisely what their position amounts to.

USE SIGNAL VERBS THAT FIT THE ACTION

In introducing summaries, try to avoid bland formulas like “she says” or “they believe.” Though language like this is sometimes serviceable enough, it often fails to reflect accurately what’s been said. Using these weaker verbs may lead you to summarize the topic instead of the argument. In some cases, “he says” may even drain the passion out of the ideas you’re summarizing.

We suspect that the habit of ignoring the action when summarizing stems from the mistaken belief we mentioned earlier, that writing is about playing it safe and not making waves, a matter of piling up truths and bits of knowledge rather than a dynamic process of doing things to and with other people. People who wouldn’t hesitate to say “X totally misrepresented,” “attacked,” or “loved” something when chatting with friends will in their writing often opt for far tamer and even less accurate phrases like “X said.”

But the authors you summarize at the college level seldom simply “say” or “discuss” things; they “urge,” “emphasize,” and “complain about” them. David Zinczenko, for example, doesn’t just say that fast-food companies contribute to obesity; he complains or protests that they do; he challenges, chastises, and indicts those companies. The Declaration of Independence doesn’t just talk about the treatment of the colonies by the British; it protests against it. To do justice to the authors you cite, we recommend that when summarizing—or when introducing a quotation—you use vivid and precise signal verbs as often as possible. Though “he says” or “she believes” will sometimes be the most appropriate language for the occasion, your text will often be more accurate and lively if you tailor your verbs to suit the precise actions you’re describing.

TEMPLATES FOR WRITING SUMMARIES

To introduce a summary, use one of the signal verbs above in a template like these:

- In her essay X, she advocates a radical revision of the juvenile justice system.

- They celebrate the fact that __________.

- __________, he admits.

When you tackle the summary itself, think about what else is important beyond the central claim of the argument. For example, what are the conversations the author is responding to? What kinds of evidence does the author’s argument rely on? What are the implications of what the author says, both for your own argument and for the larger conversation?

Here is a template that you can use to develop your summary:

- X and Y, in their article __________, argue that __________. Their research, which demonstrates that _____, challenges the idea that __________. They use __________ to show __________. X and Y’s argument speaks to __________ about the larger issue of __________.

VERBS FOR INTRODUCING SUMMARIES AND QUOTATIONS

|

VERBS FOR MAKING A CLAIM |

|

|

argue |

insist |

|

assert |

observe |

|

believe |

remind us |

|

claim |

report |

|

emphasize |

suggest |

|

VERBS FOR EXPRESSING AGREEMENT |

|

|

acknowledge |

do not deny |

|

admire |

endorse |

|

admit |

extol |

|

agree |

praise |

|

celebrate |

reaffirm |

|

concede |

support |

|

corroborate |

verify |

|

VERBS FOR QUESTIONING OR DISAGREEING |

|

|

complain |

qualify |

|

complicate |

question |

|

contend |

refute |

|

contradict |

reject |

|

deny |

renounce |

|

deplore the tendency to |

repudiate |

|

VERBS FOR MAKING RECOMMENDATIONS |

|

|

advocate |

implore |

|

call for |

plead |

|

demand |

recommend |

|

encourage |

urge |

|

exhort |

warn |

Exercises

- To get a feel for Peter Elbow’s believing game, think about a debate you’ve heard recently—perhaps in class, at your workplace, or at home. Write a summary of one of the arguments you heard. Then write a summary of another position in the same debate. Give both your summaries to a classmate or two. See if they can tell which position you endorse. If you’ve succeeded, they won’t be able to tell.

- Read the following passage from “Our Manifesto to Fix America’s Gun Laws,” an argument written by the editorial board of the Eagle Eye, the student newspaper at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, in response to the mass shooting that occurred there on February 14, 2018.

We have a unique platform not only as student journalists but also as survivors of a mass shooting. We are firsthand witnesses to the kind of devastation that gross incompetence and political inaction can produce. We cannot stand idly by as the country continues to be infected by a plague of gun violence that seeps into community after community and does irreparable damage to the hearts and minds of the American people.…

The changes we propose:

Ban semi-automatic weapons that fire high-velocity rounds

Civilians shouldn’t have access to the same weapons that soldiers do. That’s a gross misuse of the second amendment …

Ban accessories that simulate automatic weapons

High-capacity magazines played a huge role in the shooting at our school. In only 10 minutes, 17 people were killed, and 17 others were injured. This is unacceptable …

Establish a database of gun sales and universal background checks

We believe that there should be a database recording which guns are sold in the United States, to whom, and of what caliber and capacity they are …

Raise the firearm purchase age to 21

In a few months from now, many of us will be turning 18. We will not be able to drink; we will not be able to rent a car. Most of us will still be living with our parents. We will not be able to purchase a handgun. And yet we will be able to purchase an AR-15 …

- Do you think the list format is appropriate for this argument? Why or why not?

- Write a one-sentence summary of this argument, using one of the verbs from the list on pages 43–44.

- Compare your summary with a classmate’s. What are the similarities and differences between them?

- A student was asked to summarize an essay by writer Ben Adler, “Banning Plastic Bags Is Good for the World, Right? Not So Fast” (pp. 320–25). Here is the draft: “Ben Adler says that climate change is too big of a problem for any one person to solve.”

- How does this summary fall prey to the “closest cliché syndrome” (p. 35)?

- What’s a better verb to use than “say”? Why do you think so?