AMERICA | SIDE BY SIDE

Forms of Government

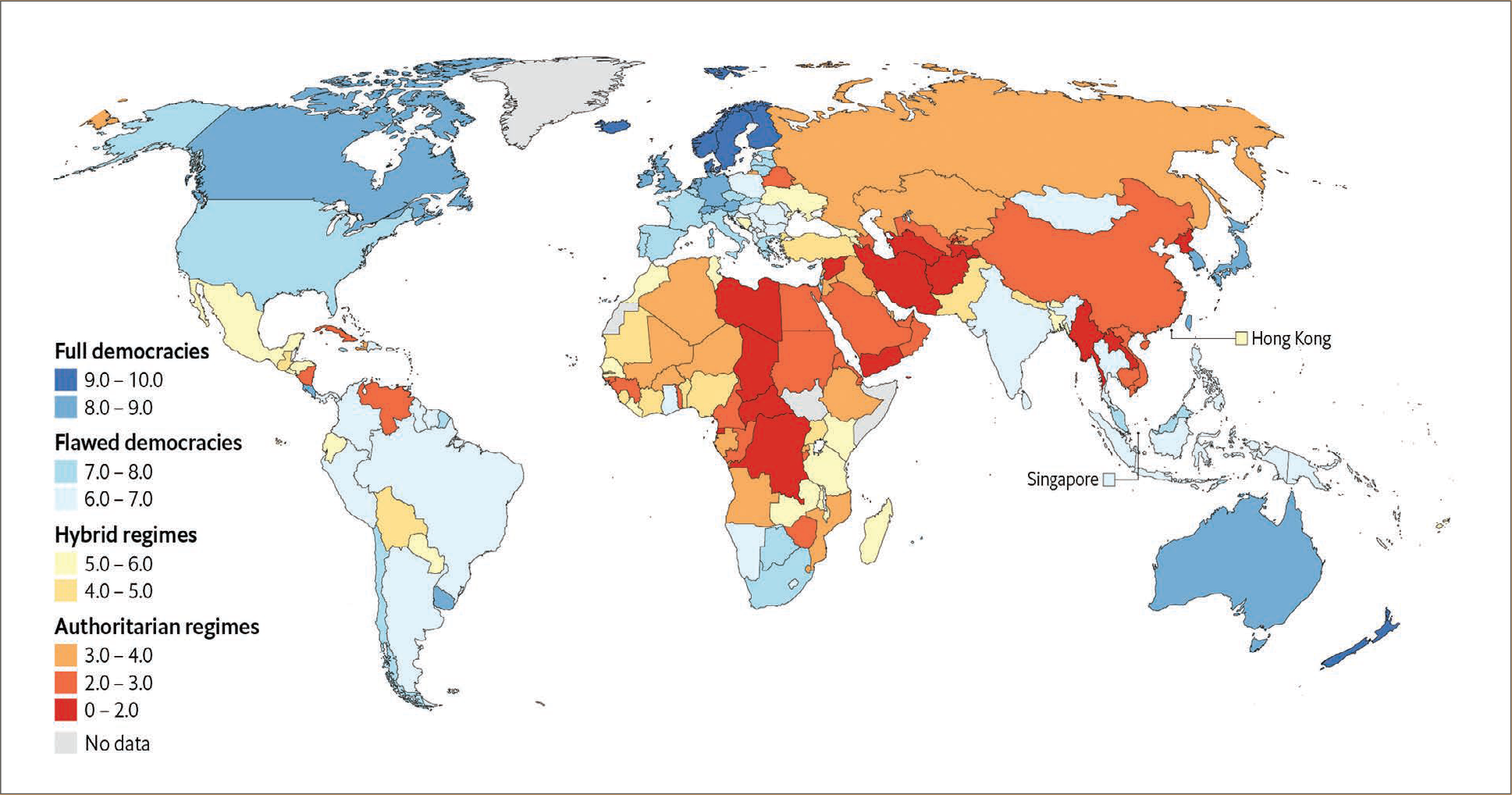

The question of whether a country is democratic or authoritarian is complex. Every year, the Economist rates countries on a scale from “Full Democracies” to “Authoritarian” systems based on expert evaluations of five factors: electoral processes, political culture, respect for civil liberties, political participation, and functioning of government. In 2016, for the first time, the United States was classified as a “Flawed Democracy” in response to declines in public confidence in governance and a rise in polarization.

- Is there a geographic pattern between the countries labeled “Full” or “Flawed” democracies and those that are labeled “Hybrid” or “Authoritarian” systems? What factors, historical, economic, geographic, or otherwise, might help to explain this pattern?

- What do you think separates a “Full Democracy” from a “Flawed Democracy”? The United States’ categorization as a “Flawed Democracy” happened during the Obama administration and persisted during the Trump and Biden administrations. What changes have you seen in the past few years that might explain this shift? How concerned should Americans be by this categorization?

More information

The world map shows forms of government for various countries. The countries are categorized as Full democracy, Flawed democracy, Hybrid regimes and Authoritarian Regimes. The data from the map are as follows. Full democracy, 9.0 to 10.0: Canada, Iceland, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Norway, Ireland, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Australia, and New Zealand. Full democracy, 8.0 to 9.0: Chile, Uruguay, San Jose, the U K, France, Germany, Austria, Spain, and Portugal. Flawed democracy, 7.0 to 8.0: the U S A, Argentina, Columbia, Ecuador, Peru, Brazil, Paraguay, the Dominican Republic, South Africa, Botswana, Belgium, Panama, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Italy, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Bulgaria, Greece, Malaysia, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan. Flawed democracy, 6.0 to 7.0: Mexico, Lesotho, Namibia, Ghana, Poland, Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Romania, Tunisia, India, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, and Mongolia. Hybrid regimes, 5.0 to 6.0: Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, Morocco, Senegal, Benin, Liberia, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Madagascar, Ukraine, Georgia, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Bhutan. Hybrid regimes, 4.0 to 5.0: Bolivia, Bosnia, Turkey, Algeria, Mali, Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, Sierra Leone, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Kyrgyzstan. Authoritarian Regimes, 3.0 to 4.0: Nicaragua, Russia, Iraq, Jordan, Oman, Ethiopia, Egypt, Niger, Mauritius, Guinea, Cameroon, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Angola, Gabon, Congo, Burma, Vietnam, and Cambodia. Authoritarian Regimes, 2.0 to 3.0: Cuba, Venezuela, Belarus, Libya, Sudan, South Sudan, Eritrea, the U A E, Kuwait, Qatar, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Iraq, Azerbaijan, China, and Laos. Authoritarian Regimes, 0.0 to 2.0: Syria, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, Turkmenistan, and North Korea. No data: Greenland, French Guiana, Somalia, and Western Sahara. The source line at the bottom of the page reads: “Democracy Index 2019,” The Economist Intelligence Unit.

SOURCE: “Democracy Index 2021,” The Economist Intelligence Unit.