Interactions: Why Can’t Actors Always Get What They Want?

Actors make choices in order to further their interests. Yet political outcomes depend not just on the choices of one actor, but on the choices of others as well. China might prefer that Vietnam, Malaysia, and other countries give up their claims to the South China Sea, but those countries have refused to do so, leading to recurrent naval clashes in the region. The United States might prefer that China make concessions to buy more American products, but China did not agree to purchase as much as the Trump administration demanded. Interests are essential in analyzing any event in international relations because they represent how actors rank alternative outcomes. But to account for the actual outcomes, we must examine the choices of all the relevant actors and how those choices interact to produce a particular result. As we use the term here, interactions are the ways in which the choices of two or more actors combine to produce political outcomes.

When outcomes result from an interaction, actors have to anticipate the likely choices of others and take those choices into account when making their own decisions. Let’s start small and consider the collision between the Vietnamese fishing boat and the Chinese vessel mentioned at the outset. Since each side claimed the waters they were in, each wanted the other side to leave the area and recognize its right to be there. From the perspective of the Vietnamese fishermen, their interests in income and personal well-being might have led to the following ordering of possible outcomes: (1) the Chinese boat leaves the area and allows them to fish there; (2) they leave the area unharmed and fish somewhere else; (3) they collide with the Chinese vessel, risking injury, death, and imprisonment. If so, their only chance of getting their best possible outcome required staying put and refusing Chinese demands that they leave. But doing so risked bringing about their worst possible outcome: getting sunk.

Whether staying put would lead to the Vietnamese fishermen’s best or worst outcome depended on what the Chinese would do in response. Would their ship ram the boat, risking an international incident, or would they back down? Whether it made sense for the Vietnamese to resist or leave depended crucially on the answer to this question. If they expected China to back down, then resisting the demand to leave would secure their best outcome; if they expected the Chinese ship to carry out its threat, then resistance would lead to their worst outcome, and it would be better to leave. Hence, in making their choice, the Vietnamese side had to consider not only what they themselves wanted but also what they expected the other side to do. In this case, a collision occurred, apparently because the Vietnamese boat decided to risk a confrontation. Had they been certain that this would be the outcome, they might have chosen differently, even though their underlying interests were the same.

Although this showdown took place on a small scale, it is an example of an interaction that happens regularly in international politics as actors maneuver to get their way while trying to avoid costly collisions, whether those be trade wars or shooting wars. We call such situations strategic interactions because each actor’s strategy, or plan of action, depends on the anticipated strategy of others. Many of the most intriguing puzzles of international politics derive from such interactions.

We make two assumptions in studying interactions. First, we assume that actors behave with the intention of producing a desired result. That is, actors are assumed to choose among available options with due regard for their consequences and with the aim of bringing about outcomes they prefer. Second, in cases of strategic interaction, we assume that actors adopt strategies according to what they believe to be the interests and likely actions of others. That is, actors develop strategies that they believe are their best response to the anticipated strategies of others. In the preceding example, if the Vietnamese fishermen believed that China would back down from its threat, the best response was to resist the demand to leave; if they believed that the Chinese ship would ram them, then the best response was to comply with China’s demand, even though doing so would have meant accepting a second-best outcome. A best-response strategy is the actor’s plan to do as well as possible in light of the interests and likely strategies of the other relevant actors. Together, these assumptions link interests to choices and, through the interaction of choices, to outcomes.

Formulating a strategy as a best response, of course, does not guarantee that the actor will obtain its most preferred or even a desirable outcome. Sometimes the choices made by others leave actors facing a highly unwelcome outcome, one that may leave them far worse off than the status quo. If one state chooses to initiate a war, for instance, the other state must respond by either giving in to its demands or fighting back, and both options may leave the second state worse off than before the attack. A strategy is a plan to do as well as possible, given one’s expectations about the interests and actions of others. It is not a guarantee of obtaining one’s most preferred result.

Understanding the outcomes produced by the often complex interplay of the strategies of two or more actors can be difficult. A specialized form of theory, called game theory, has been invented to study strategic interactions. We offer a brief introduction to game theory in the “Special Topic” appendix to this chapter (p. 86), focusing on relatively simple games to communicate the core ideas behind strategic interaction.

Cooperation and Bargaining

Interactions can take various forms, but most can be grouped into two broad categories: cooperation and bargaining. Political interactions usually involve both forms in varying degrees.

Interactions are cooperative when actors have a shared interest in achieving an outcome and must work together to do so. Cooperation occurs when two or more actors adopt policies that make at least one actor better off without making any other actor worse off. Opportunities for cooperation arise all the time in social and political life. For example, when a group of friends wants to throw a party, they may find that none of them can spare the time or money to do so alone. But if they all contribute a little, they can each enjoy the benefits of throwing the party. The members of a community all benefit if there are good roads to drive on and clean water to drink, but again, most likely no individual alone is able to provide these. If they all agree to pay taxes to a central agency that will provide roads and water, then they can all be better off. A group of firms may share an interest in lobbying Congress for trade protection from foreign imports. By pooling their resources and acting together, they may be more effective at getting their way than each individual firm would be on its own. In the international system, states may have opportunities to cooperate to defend one another from attack, to further a shared interest in free trade or stable monetary relations, to protect the global environment, or to uphold human rights.

We will look more closely at each of these types of situations in the following chapters. In the case of the South China Sea, China’s expansive maritime claims threaten those of every state bordering on that body of water (see Map 2.1), but particularly Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia. Thus, all of these states share an interest in resisting China’s demands. Although they are all individually weak relative to China, they are in a stronger position to resist Chinese demands by working together, especially with the support of the United States, which opposes Chinese control of the waterway for security and economic reasons. These common interests provide a possible basis for cooperation.

There are also possibilities for cooperation between China and the United States. China has benefited greatly from an international economic system that has few barriers to trade. Its growth in recent decades has been fueled by its ability to export low-cost manufactured goods to the rest of the world. The United States has also benefited from the openness of the trading system, which has been a boon to U.S. exporters, multinational companies, and consumers. Although job losses in sectors hurt by imports have provoked opposition to free trade in recent years—and particularly trade with China—economists estimate that, overall, trade increases employment in the United States.6 (For more on the distributional consequences of international trade, see Chapter 7.) To the extent that the open trading system benefits both countries, they have a common interest in sustaining it.

Cooperation is defined from the perspectives of the two or more actors who are interacting. Even though cooperation may benefit the actors who are directly involved, it may hurt other parties. The friends agreeing to throw a party together may disrupt their neighbors by making noise late into the night. Firms that cooperate to lobby Congress for trade protection may impose higher prices on consumers. Cooperation to oppose China’s demands in the South China Sea would obviously harm Beijing’s interest in the territory. Cooperation between the United States and China on trade could come at the expense of workers in some sectors who might lose their jobs. Indeed, cooperation is not always an unmitigated good; its benefits exist only for those who adjust their policies to bring about an outcome they prefer.

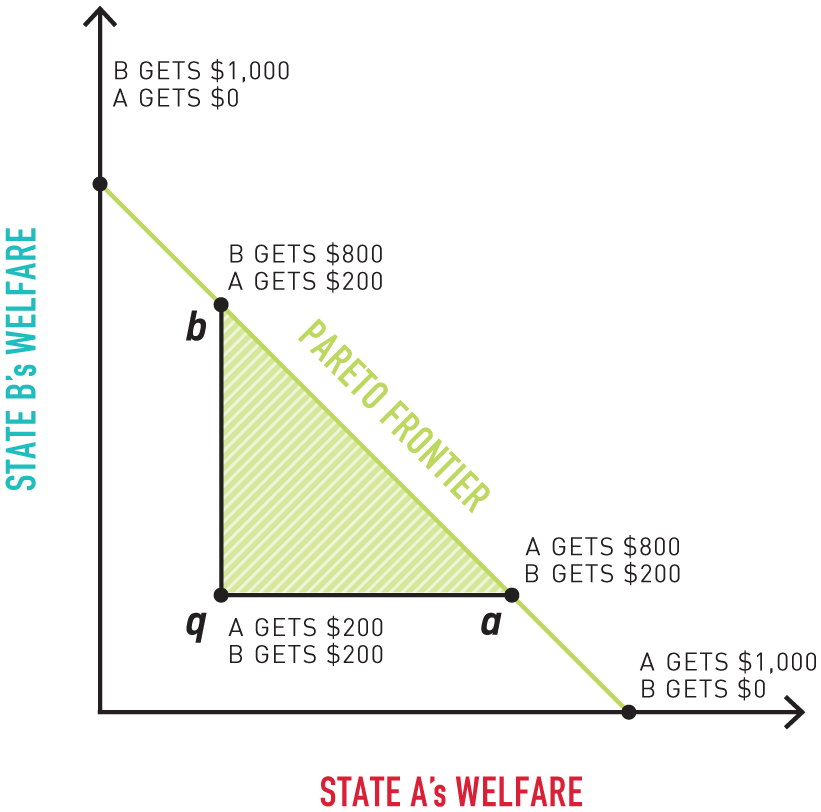

Figure 2.2 depicts in simple terms the problem of cooperation between two actors. Imagine that two actors can enact policies that have the potential to increase their overall income or welfare. The income of the actors is plotted along two dimensions, with Actor A’s income increasing along the horizontal axis and Actor B’s income increasing along the vertical axis. Since the concept is easier to illustrate with a divisible good like money, we use dollars in the example, but welfare is the more general concept, which includes not only income but other desired goods or outcomes. All points within the graph represent possible outcomes produced by different combinations of policies chosen by the two actors.

Assume that by cooperating, the two actors can make as much as $1,000, a limit determined in this case by the available technology and resources. This limit is depicted by the downward-sloping line in Figure 2.2, which shows all the different ways $1,000 can be divided between the two actors. The point at which the line touches the horizontal axis depicts a situation in which Actor A gets $1,000 and Actor B gets nothing, the point at which the line touches the vertical axis depicts a situation in which Actor B gets all the money, and every point in between represents different divisions of the maximum feasible income. For example, if the two actors cooperate to make the maximum income in such a way that State A gets $600, then State B gets $400; if State A gets $200, then State B gets $800. This line representing the possible divisions of the maximum feasible benefit is called the Pareto frontier, after the Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923), who developed these ideas.

In this world, there is $1,000 worth of a good that can be captured by State A and State B. In the status quo, State A gets $200 and State B gets $200. Through cooperation, both states can improve their outcomes by capturing and sharing the remaining $600. The green-shaded triangle—defined by the points q, a, and b—outlines all possible superior outcomes.

However, the actors may have chosen policies that do not result in the maximum possible benefit. Let’s assume that past policy combinations have produced an outcome referred to as the status quo (q). As q is depicted in Figure 2.2, the actors are not doing as well as they could, with each making $200, for a total of $400 rather than $1,000. This means that they could potentially benefit by changing their policies to get closer to the Pareto frontier line and thus to the maximum feasible income. Any policy combination that leads to an outcome in the shaded area qba would make both actors better off than they are under the status quo. Moving outward from q, into the shaded area, represents cooperation, or an improvement in the welfare of at least one actor.

We can see that policies along the line segment between q and a improve A’s welfare at no loss to B, while policies along the line segment between q and b improve B’s welfare at no loss to A. Any movement into the shaded area defined by points q, b, and a represents an improvement in the welfare of both actors, and any policy combination on the Pareto frontier between b and a makes the actors as well off as possible, given available resources and technology. Cooperation consists of mutual policy adjustments that move actors toward or onto the Pareto frontier, increasing the welfare of some or all partners without diminishing the welfare of any one actor. Because it makes at least one party better off than otherwise, we refer to cooperation as a positive-sum game.

Bargaining describes interactions in which actors must decide how to distribute, or divide, something of value. For example, two states may want the same piece of territory, just as Vietnam and China both want the Paracel/Xisha Islands and the surrounding waters. Bargaining describes the process by which they come to divide the territory. They may negotiate, impose sanctions on one another, engage in threats or displays of force, or fight. All these tactics are different forms of bargaining. Given the nature of the situation, the more territory one side gets, the less the other gets.

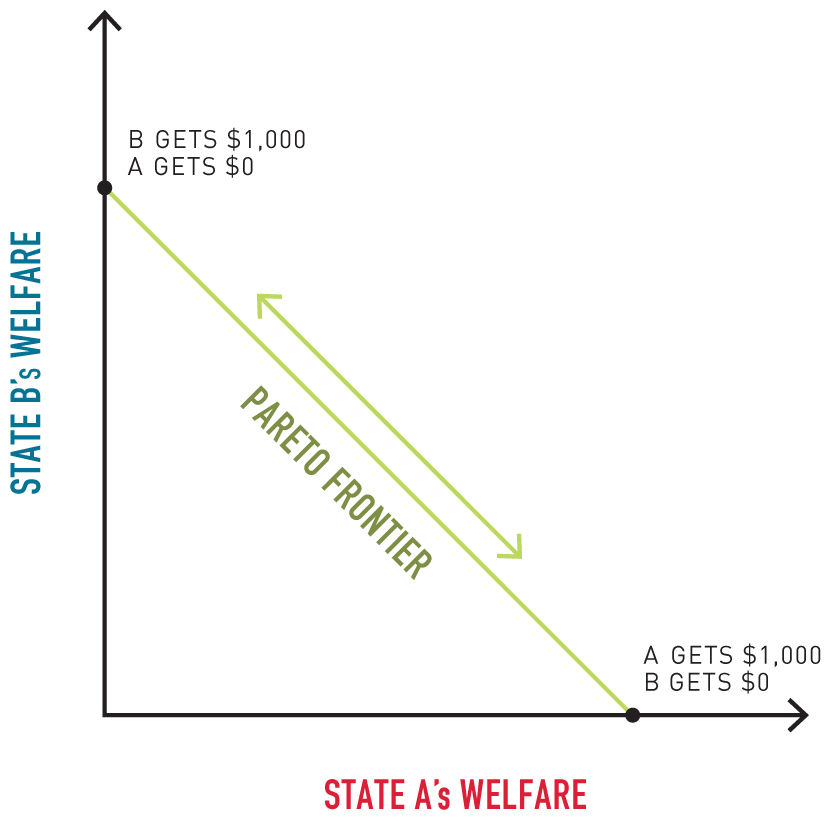

State A and State B are bargaining over the division of $1,000. Each point along the line is a possible division. For every $1 that State A gains, State B loses $1, and vice versa.

Bargaining is illustrated in Figure 2.3. When actors bargain, they move along the Pareto frontier, as represented by the green arrow. On the frontier line, any improvement in A’s welfare comes strictly at the expense of B’s welfare. For example, if Actor A gains 100 percent of a contested piece of territory under a given bargain, that means Actor B gets 0 percent of the territory; if Actor A gives up 20 percent of the territory through bargaining, Actor B gains that 20 percent of the territory.

Bargaining interactions are characterized by distributional conflict, as each actor seeks a greater share of the good at the expense of the other; however, to reach a bargain, both sides must decide that a deal is better than the alternative. A car buyer and a car seller may haggle over the price of the car, but ultimately they will agree to a price only if both prefer that price to making no deal. Similarly, while two states may bargain hard over how to divide a piece of territory, they will agree to a deal only if each believes that the alternative, which may involve fighting a war, is worse. Indeed, we typically represent war as the outcome of a bargaining interaction in which the adversaries are unable to agree to a peaceful deal (see Chapter 3). While bargaining interactions are defined by their redistributive nature, bargains generally create value for both sides relative to the alternative of no deal.

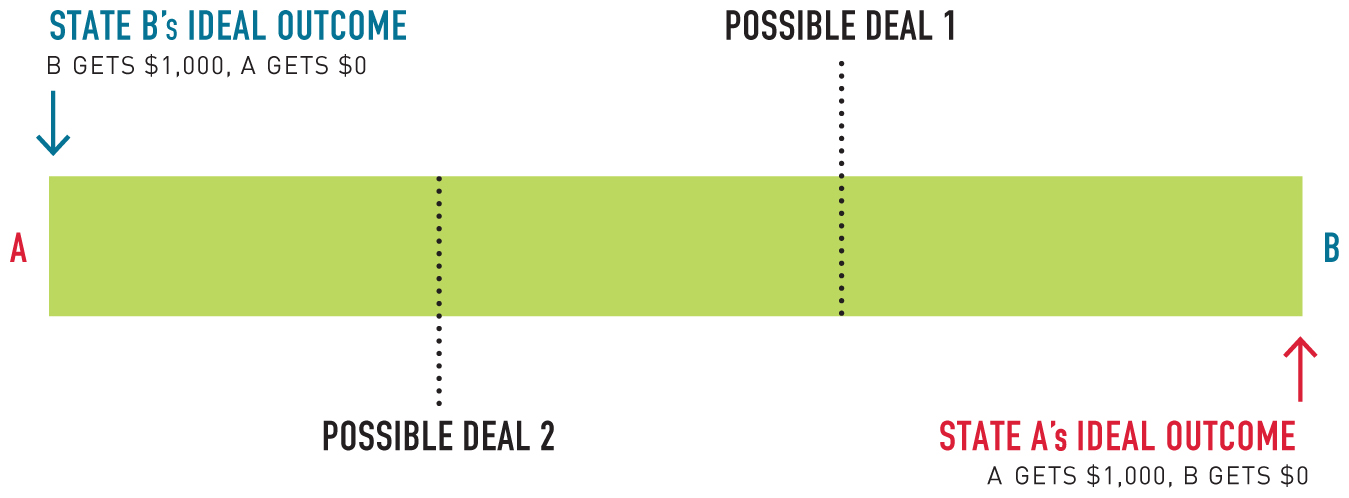

Through cooperation, State A and State B can improve their joint outcome from the starting point—the status quo—to capture an additional $600. But they have to bargain over exactly how that $600 will be divided between them.

Thus, while we treat cooperation and bargaining as distinct phenomena, most interactions in international relations combine elements of both (Figure 2.4). Although both states may gain by moving to the frontier, A prefers bargains that leave it closer to a, whereas B prefers bargains that leave it closer to b. Movement toward the frontier makes at least one actor better off, but where on the frontier they end up makes an important difference. For example, even if China and the United States want to cooperate to sustain an open trading system, their policy choices have distributional consequences and can lead to hard bargaining over the terms of cooperation. Often, actors are cooperating and bargaining simultaneously, and the outcomes of both interactions are linked. Successful cooperation generates gains worth bargaining over. And if the actors cannot reach a bargain over the division of gains, they may end up failing to cooperate.7

Cooperation and bargaining can succeed or fail for many reasons. Just because actors might benefit from cooperation does not mean they will actually change their policies to realize the possible gains. And even though bargaining might seem doomed to fail—after all, why would one actor agree to reduce its welfare?—actors often do succeed in redistributing valuable goods between themselves. We now turn to some of the primary factors that influence the success or failure of cooperation and, later, of bargaining.

When Can Actors Cooperate?

If cooperation makes actors better off, why do they sometimes fail to cooperate? By far the most important factor is each actor’s interests. Even when actors have a collective interest in cooperating, situations exist in which their individual interests lead them to “defect”—that is, to adopt an uncooperative strategy that undermines the collective goal. The strength of the incentives to defect goes a long way toward determining the prospects for cooperation.8

Consider the easiest kind of cooperative interaction, what we call a problem of coordination. This kind of situation arises when actors need only coordinate their actions with one another, and once their actions are coordinated, none receive any benefit from defecting. A classic example is deciding which side of the road cars should drive on. Drivers have a shared interest in avoiding crashes, so they are always better off if all drive on the right or on the left, rather than some driving on each side of the road. It does not matter which side of the road is selected. Indeed, different countries have different rules: cars drive on the right side of the road in the United States and continental Europe and on the left side in Great Britain, South Africa, and Japan. What matters is that all drivers in the region make the same choice. Moreover, no driver would intentionally deviate from that choice, since doing so would be very dangerous. In short, there is no incentive to defect from the coordinated arrangement.

In the international economy, firms, industries, and even governments face coordination problems all the time, as suggested by the numerous agreements on international standards. There are many ways to encode information to be sent over the Internet, for instance, but all firms that produce devices connected to the Internet—computers, smartphones, gaming devices, and the like—are better off coordinating on a single format. Similarly, it is important that international airline pilots speak a single language so as to communicate effectively with one another and with air traffic controllers worldwide; although any language could in principle serve this role, English became the standard due to the dominance of the United States. In coordination situations, cooperation is self-sustaining because once coordination is achieved, no one can benefit by unilaterally defecting.

A more serious barrier to cooperation arises if the actors have an individual incentive to defect from cooperation, even though cooperation could make everyone better off. Cooperative interactions in which actors have a unilateral incentive to defect are called problems of collaboration. This kind of problem is often illustrated by a simple game called the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Imagine that two criminals have been detained by the police for committing a crime together. The district attorney does not have enough evidence to convict them on felony charges but can convict each suspect of a misdemeanor. She confines the prisoners separately and presents each with the following offer: “If neither of you is willing to testify, I will charge both of you with a misdemeanor and sentence you each to one year in prison. If you defect on your accomplice by providing evidence against him, I will let you go free and will put him in prison for ten years. However, he has been offered the same deal. If he provides evidence against you, you’ll be the one behind bars. Finally, if you both squeal on one another, you’ll each be charged with a felony, but your sentences will be reduced to five years in exchange for testifying.”

Collectively, the prisoners would do best by cooperating with each other and refusing to testify; they would, together, serve a total of only two years behind bars. However, the prisoners are motivated not by the collective outcome but rather by the desire to shorten their own individual sentences. Thus, each has an incentive to rat out the other. Each prisoner reasons as follows: “Suppose my partner stays quiet. In that case, I should defect on him so that I will be released immediately rather than remain quiet and spend a year behind bars. On the other hand, suppose that my accomplice plans to defect on me. In that case, I should also defect on him, because giving testimony will reduce my sentence to five years rather than the ten I will face if I stay quiet.”

Because both prisoners reason the same way, both will end up providing evidence against the other and both will be imprisoned for five years. This outcome, of course, is worse for each of them than the outcome they could achieve if they cooperated with one another and remained silent; the dilemma is that each individual’s incentive to defect against the other undermines their collective interest in cooperation. For a more formal and complete discussion of this dilemma, see the “Special Topic” appendix to this chapter (p. 86), a discussion of game theory that includes the Prisoner’s Dilemma.

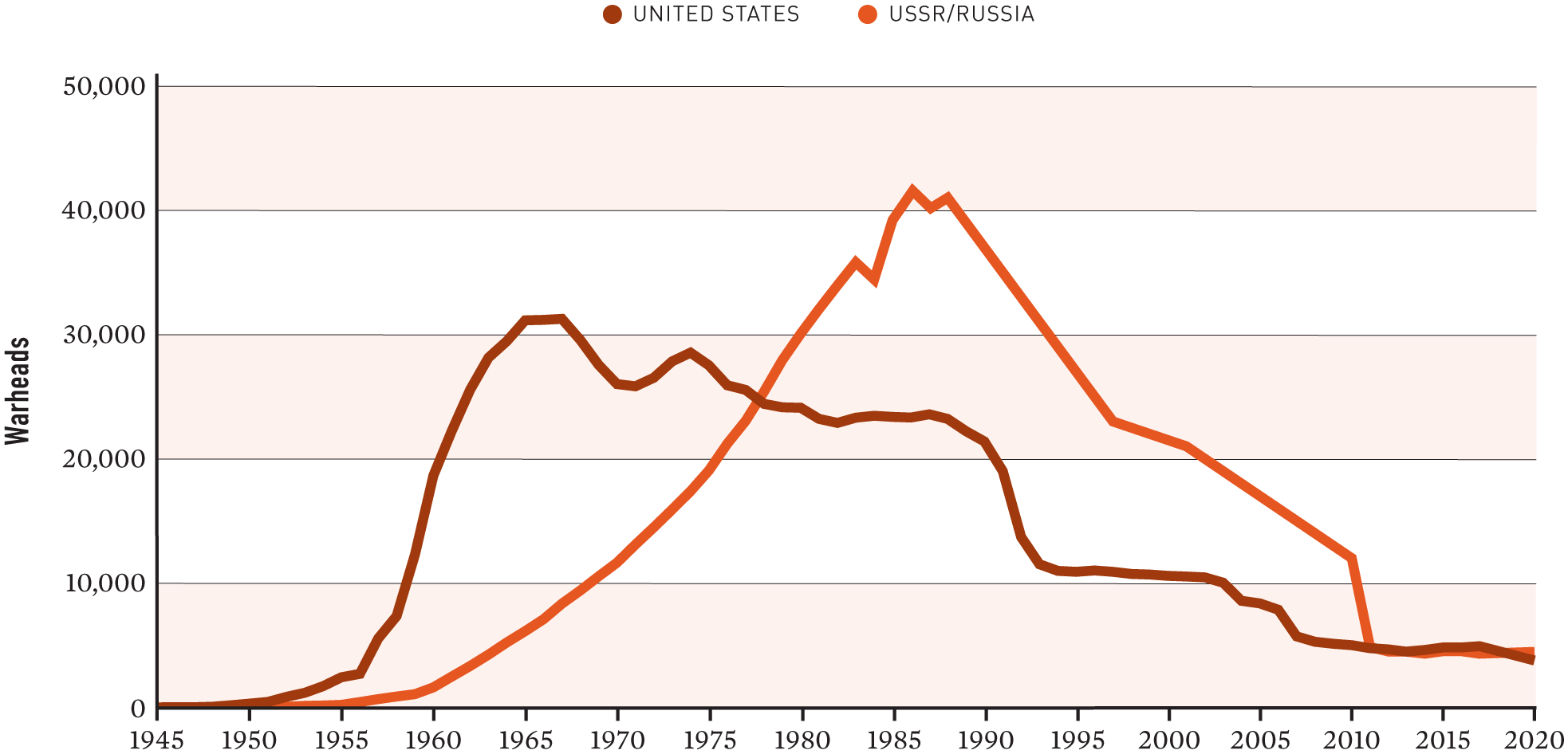

Although the dilemma of fictional prisoners may seem remote from the subject matter of this book, analogous situations often arise in international relations. Consider the nuclear arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Both countries built costly nuclear weapons at a furious pace, such that by the late 1980s the United States had about 23,000 nuclear weapons, while the Soviet Union had about 42,000 (Figure 2.5).

One might ask, Why not agree to stop building when the United States had 2,300 warheads and the Soviet Union had 4,200? Stopping at that point would have kept the same ratio of forces but at a much lower cost. Both states might have been better off with such an agreement. The problem, however, is that each state had an incentive to cheat on such a deal in order to attain (or maintain) superiority over the other. If one stopped building, the other would be tempted to keep going. Therefore, each feared that its own restraint in building weapons would be exploited, leaving it vulnerable. Given these incentives and fears, the best strategy for each state was to go on amassing weapons. As a result, both countries ended up worse off than if they could have cooperated to limit their arms competition.9

A specific type of collaboration problem arises in providing public goods, which are products such as national defense, clean air and water, and the eradication of communicable diseases. Public goods are defined by two qualities. First, if the good is provided to one person, others cannot be excluded from enjoying it as well (formally, the good is nonexcludable). If one person in a country is protected from foreign invasion, for instance, all other citizens are also protected. Second, if one person consumes or benefits from the public good, the quantity available to others is not diminished (formally, the good is nonrival in consumption). Again using the example of national defense, one person’s enjoyment of protection from foreign invasion does not diminish the quantity of security available to others. Many global environmental issues, such as ozone depletion and climate change, are also public goods (as we will discuss in more detail in Chapter 13).

Public goods are contrasted with purely private goods, which are products that only one person can possess and consume. Your sandwich for lunch is a private good: if it’s available to you, it is not automatically available to all others, and if you eat it, it is not available to be eaten by any others.

Efforts to produce public goods always face collective action problems, which we will encounter many times in this book. Given that actors can enjoy public goods whether or not they contribute to the provision of those goods, each prefers that others pay to produce the good while it gets to enjoy the good for free. That is, each actor aims to benefit from the contributions of others without bearing the costs itself. For example, individuals would prefer to benefit from national security without paying taxes or volunteering for military service. Similarly, all states might want a genocide to be stopped, but each would prefer that others assume the risks of the necessary military intervention. In such situations, even though everyone wants the public good to be provided, each individual has an incentive to free ride by not contributing while benefiting from the efforts of others. When contributions are voluntary, free riding leads public goods to be provided at a lower level than that desired by the actors.

This is why public goods are often provided by governments, which have the power to tax citizens or otherwise mandate their contributions. Free riding is no longer so attractive if, say, the failure to contribute taxes can lead to steep fines or imprisonment. This is also why collaboration among governments on global issues can prove so difficult, as there is no international authority that can force countries to contribute to the provision of global public goods.

As this discussion suggests, some of the problems associated with cooperation are addressed by institutions, which might be able to alter actors’ incentives so that their individual interests line up with the collective interest. The role of institutions in promoting cooperation is discussed later in this chapter. Even in the absence of institutions, though, we can identify several factors that facilitate cooperation.

Numbers and Relative Sizes of Actors

It is easier for a small number of actors to cooperate and, if necessary, to monitor each other’s behavior than for a larger number of actors to do so. Two actors can communicate more readily and observe each other’s actions better than a thousand actors can. Thus, the smaller the number of actors, the more likely they are to cooperate successfully. As we will see in Chapter 7, firms can organize more easily to lobby their governments for trade protection than can consumers, who are typically more numerous. Environmental agreements are easier to monitor and enforce—thus, more likely to be agreed upon—among small groups of countries.

In the case of public goods, moreover, some groups may have a single member or a small coalition of members willing to pay for the entire public good. This could happen if these members receive benefits from the public good sufficient to offset the entire costs of providing it. In such privileged groups, the single member or small coalition of members provides the public good despite free riding by others.10

As we will see in Chapter 5, international efforts to reverse acts of aggression generally require that a very powerful state, such as the United States, be motivated to conduct a military operation largely on its own. Similarly, success in limiting ozone emissions (see Chapter 13) stemmed in part from the disproportionately large role of the United States, Russia, and Japan in the industries responsible for the emissions. Some analysts attribute the economic openness of the international economy in the mid-nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries to public goods like the international monetary regime provided unilaterally by Britain and the United States, which were the largest powers in those eras, respectively.

Iteration, Linkage, and Strategies of Reciprocal Punishment

Cooperation is more likely when actors have opportunities to cooperate over time and across issues. The incentive to defect or free ride in any given interaction can be overcome if actors expect to be involved in multiple, repeated interactions with the same partners.11 In this situation—commonly known as iteration—actors can prevent one another from cheating by threatening to withhold cooperation in the future. Even when an actor has incentives to defect in the current interaction, knowing that the other actor will refuse to cooperate with it in the future can offset those temptations. Thus, “good behavior” can be induced today by the fear of losing the benefits of cooperation tomorrow. Countries are less likely to cheat on a trade agreement with a country they trade with often and expect to trade with again in the future (see Chapter 7). The threat of reciprocal punishment can be a powerful tool for enforcing cooperation even when actors are tempted to cheat.12 You are more likely to leave a generous tip for the waiter at a local restaurant that you think you’ll frequent in the future—lest you get poor service on another visit—than you are in a restaurant you don’t expect ever to visit again.

In one particularly telling example of how frequent interaction can generate cooperation, a system of “live and let live” emerged during the trench warfare of World War I. After an initial period of rapid gains, troops on both sides of the war bogged down in fixed trenches within rifle range of one another. Despite incentives to kill the enemy whenever possible, lest he kill you, many areas along the trenches developed a form of restrained cooperation in which, even in the absence of any communication, the troops stationed there did not fire upon one another. Occasional failures of cooperation, when shooting began for some reason, were punished by two-for-one or three-for-one retaliation by the other side. This response usually led back to restraint and renewed cooperation. What made cooperation possible even in this most unlikely of circumstances was the long-term deployment of troops in the same area, creating iteration and reciprocity in action.

Closely related to iteration is the concept of linkage, which ties cooperation on one policy dimension to cooperation on other dimensions. Whereas iteration enables victims to punish cheaters by withholding the gains from future cooperation, linkage enables victims to retaliate by withholding cooperation on other issues. Defection on military affairs, for instance, might be punished by withdrawing cooperation on economic matters. If actors know the failure of cooperation on one dimension puts cooperation on other issues at risk, then they have more incentive to cooperate on all.

Information

One final factor that affects the likelihood of cooperation is the availability of information. In some cases, it is easy to observe whether a partner has cooperated or defected, such as when cooperation entails a public act like participating in a military operation. In other cases, however, cooperative and uncooperative acts may be hard to observe or distinguish from one another. If cooperation involves reducing armaments, for example, the fact that states can build weapons in secret means that defection may go unobserved.

When actors lack information about the actions taken by another party, cooperation may fail because of uncertainty and misperception.13 A state might defect under the mistaken belief that it can get away with it or because it doubts other parties will abide by the terms of cooperation. Alternatively, cooperation might unravel if cooperative acts are mistaken for defection. Suppose one party mistakenly believes that the other has defected and cuts off cooperation as punishment; the other party, which has been cooperating all along, then perceives the first actor’s punishment as a new defection and cuts off cooperation in retaliation. Simple misperceptions can lead to hostile punishments and the breakdown of cooperation, even though all actors thought they were acting cooperatively.14

Who Wins and Who Loses in Bargaining?

Whereas cooperation has the potential to make actors collectively better off, bargaining creates winners and losers: the more one actor gets from a bargain, the less others can have. When two or more actors desire the same good—for example, a sum of money or a piece of territory—it is impossible for all of them to get their best possible outcome at the same time. Why, then, are bargains ever reached? Why do actors consent to losses? What determines who wins and who loses?

Considering these questions introduces a core concept in international politics: power. In the standard definition, which we owe to the political scientist Robert Dahl, power is the ability of Actor A to get Actor B to do something that B would otherwise not do.15 In the context of bargaining, power is most usefully seen as the ability to get the other side to make concessions and to avoid having to make concessions oneself. The more power an actor has, the more it can expect to get from others in the final outcome of bargaining.

Power is one of the most frequently used yet ambiguous terms in the study of international relations. Sometimes it is understood as an end in itself—an interest, as we have defined that concept—and sometimes as a means toward other ends. Other times power is conceived as a reality or set of circumstances created by past interactions that structure or constrain the choices currently available to actors. Their large economies, past investments in military forces, and large stockpiles of nuclear weapons, for instance, gave the United States and the Soviet Union enormous political advantages over other countries during the Cold War, deterring other states from even contemplating challenging the core interests of either superpower.

Our focus here, in the context of explaining bargaining outcomes, is what is sometimes called compulsory power, or the ability of one actor to compel another to act in certain ways.16 Understood in this way, the outcome of any bargaining interaction is fundamentally influenced by what would happen in the event that no bargain was reached. The outcome that occurs when no bargain is achieved is often called the reversion outcome. In some cases, the reversion outcome is the same as the status quo. For example, if a car buyer and a prospective seller cannot agree on a price, then the seller is left with his car and the buyer keeps her money. What is lost is a chance to make a potentially profitable deal.

When actors bargain over the terms of cooperation, a failure to agree can prevent the collective benefits from being enjoyed. For example, if states contemplating intervention in a civil war or negotiating an environmental treaty cannot agree on how to divide the costs, then the civil conflict will rage on or the environmental harm will continue. In other cases, the consequences of disagreement are more severe: the reversion outcome may be a war or some other kind of conflict, such as economic sanctions, that leaves one or even both actors worse off than they were before the dispute began.

The actor that would be more satisfied with the reversion outcome generally has less incentive to make concessions in order to reach a successful bargain. Conversely, the actor that would be less satisfied with the reversion outcome becomes desperate to reach an agreement and thus offers relatively bigger concessions in the hopes of inducing the more satisfied actor to agree. In short, bargaining power belongs to those actors who would be most satisfied with, or most willing to endure, the reversion outcome. In the car-buying example, if the seller needs money and is anxious to sell the car quickly, a more patient buyer can extract a better deal.

Internationally, in negotiations over global climate change, the United States has been less willing to go along with other countries in part because the expected costs of climate change to the United States are lower. Given its geography and economic resources, the United States is better equipped than many other states to weather the effects of a warming planet and rising sea levels. Lower vulnerability to these harms has helped sustain opposition in the United States to complying with greenhouse gas limitations mandated in international environmental agreements, effectively shifting the burden of cuts onto other countries (see Chapter 13).

Because bargaining outcomes are determined largely by how each actor evaluates the reversion outcome, power derives from the ability to make the reversion outcome better for oneself and/or worse for the other side. To shift the reversion outcome in their favor, actors have three basic ways of exercising power: coercion, outside options, and agenda setting.

Coercion

The most obvious strategy for exercising power is coercion. Coercion is the threat or imposition of costs on other actors to reduce the value of the reversion outcome (no agreement) and change their behavior. Thus, states can use their ability to impose costs on others to demand a more favorable bargain than they would otherwise receive. China’s harassment of fishing boats and survey vessels in the South China Sea seeks to make those activities costlier for other states in the hope that they will concede their rights to the disputed waters. President Trump’s decision in 2018 to enact tariffs on Chinese imports was an attempt to impose costs on the Chinese economy in order to compel concessions on trade. The target of coercion, of course, can itself try to impose costs in response, and indeed China’s retaliatory tariffs against the United States hurt farmers who depend on exports into the Chinese market.17

Means of international coercion include military force and economic sanctions. The ability to impose costs on others and to defend against costs that others would seek to impose derives in large part from material capabilities—the physical resources that enable an actor to inflict harm and/or withstand the infliction of harm. In coercive interactions among states, these capabilities are often measured in terms of military resources—such as the number of military personnel or level of military spending—as well as measures of economic strength, since economic resources can be converted into military power. The balance of such capabilities among states is a strong predictor (though not the only one) of who wins and who loses in warfare.18 Similarly, the size of a country’s economy has an impact on its ability to impose and/or withstand economic sanctions, which cut off a country’s access to international trade.

Simply being able to impose higher material costs than the other side is not enough ensure successful coercion, however. In determining whether to give in to another’s demands, an actor has to compare the costs it will incur from no agreement to the value of whatever concessions are being demanded. If both sides value the issue in question equally, then the side that can impose higher costs is likely to prevail. But if one side cares more intensely about whatever is in dispute, it may be willing to withstand much higher costs without giving in.

This helps explain why weak states can at times defeat great powers. When France tried to reassert colonial control over Vietnam after World War II, the leader of the Vietnamese resistance, Ho Chi Minh, warned the French that their superior military power would not matter: “You will kill ten of our men, and we will kill one of yours, and in the end it will be you who tire of it.”19 The Vietnamese leader’s optimism sprang from the belief that, while the French were fighting for an overseas colony, his people were fighting for their homeland, and they were thus willing to bear higher costs of war. His bargaining power stemmed not from military capabilities but from what we will refer to in Chapter 3 as resolve.

Outside Options

Actors can also get a better deal when they have attractive outside options, or alternatives to reaching a bargain with a particular partner that are more attractive than the status quo. In this case, the reversion outcome is the next-best alternative for the party with the outside option. An actor with an attractive alternative can walk away from the bargaining table more easily than can an actor without such an option.

The actor with the better outside option can use its leverage to get a better deal or resist pressure to concede. For example, during U.S.-China trade negotiations, China restricted soybean imports from American farmers in order to pressure the Trump administration to back down. In order to meet its people’s strong demand for soybeans, China turned to alternative suppliers, particularly Brazil.20 The availability of this outside option allowed China to continue resisting American trade pressure without forgoing a key food product. By contrast, the United States lost leverage over China due to the fact that China supplies key products on which the United States depends, such as surgical masks and other personal protective equipment necessary for combating the COVID-19 pandemic and products that American companies require as part of their production processes. Some in the United States called for a “decoupling” of the two economies precisely to reduce this dependence and create more outside options.

As with coercion, the relative attractiveness of each actor’s outside options is what matters. Both actors may have alternatives, but the one with the more attractive outside option can more credibly threaten to walk away and, therefore, can get the better deal. In competitive economic markets with many buyers and sellers, for instance, little power is exercised by any given actor, since every buyer and seller has equally attractive outside options.

Agenda Setting

Finally, actors might gain leverage in bargaining through agenda setting. Agenda setting consists of actions taken before or during bargaining that make the reversion outcome more favorable for one party. A party that can act first to set the agenda transforms the choices available to others. For example, by sponsoring legislative proposals, calling public attention to issues, and cajoling individual legislators, the president of the United States has important agenda-setting power in Congress. Faced with a presidential proposal or a presidentially inspired public outcry, legislators often have little choice but to respond to the president’s initiative; they do not necessarily have to agree with the president’s proposal, but they must respond to an issue they might otherwise have preferred to avoid.21

Agenda-setting power exists between countries when states can take unilateral actions that alter the options available to others. When the United States deregulated its airline industry to capitalize on its market position and benefit its domestic consumers, other countries were forced to deregulate their industries as well in order to remain competitive, often over the opposition of their national air carriers. In territorial disputes, agenda setting can take the form of a “fait accompli,” a French term that means “accomplished fact,” which in this context refers to seizing a disputed piece of territory before the other state can react.22 By taking a piece of territory and fortifying it against attack, a state can move the reversion point to its most preferred outcome and make it hard for its adversaries to undo the act. For example, China has bolstered its leverage in the South China Sea by building military fortifications on some of the larger islands. In doing so, the Chinese have not only taken possession of those islands but also made it harder for other countries to dislodge them.

Even though bargaining creates winners and losers, bargains can be made as long as they give all parties more than (or at least as much as) they can expect to get in the reversion outcome. In other words, actors consent to painful concessions when the consequences of not agreeing are even more painful. As we will see in Chapter 3, the fact that bargains exist that all sides prefer over war does not guarantee that those bargains will always be reached. A host of problems can prevent actors from finding or agreeing to mutually beneficial deals. For example, uncertainty about how each side evaluates its prospects in a war can make it hard to know which bargains are preferable to war. There may also be situations in which states cannot credibly promise to abide by an agreement that has already been made. Bargaining may also be complicated if the good being bargained over is hard to divide. (Since this is a broad topic, we leave fuller consideration of these issues for Chapter 3.)

In sum, both interests and interactions matter in politics. Political outcomes depend on the choices of two or more actors. Since political outcomes are contingent on the choices of multiple actors, any given actor does not always or even most of the time obtain its most preferred outcome. Indeed, in bargaining, an actor may be worse off afterward than it would be if it had never entered the interaction. Interactions are often quite complex, but they are critical to understanding how interests are transformed into outcomes—often in paradoxical ways.

Prep | Check Your Understanding

Prep | Check Your Understanding

- Question: What kind of problem does the Prisoner’s Dilemma story illustrate?

- coordination

- collaboration

- linkage

- coercion

- Question: Imposing some cost on others to reduce the value of the reversion outcome is known as

- reversion.

- linkage.

- coercion.

- collaboration.

Glossary

- interactions

- The ways in which the choices of two or more actors combine to produce political outcomes.

- cooperation

- An interaction in which two or more actors adopt policies that make at least one actor better off relative to the status quo without making others worse off. Compare bargaining.

- bargaining

- An interaction in which two or more actors must decide how to distribute something of value. In bargaining, increasing one actor’s share of the good decreases the share available to others. Compare cooperation.

- coordination

- A type of cooperative interaction in which actors benefit from all making the same choices and subsequently have no incentive not to comply. Compare collaboration.

- collaboration

- A type of cooperative interaction in which actors gain from working together but nonetheless have incentives not to comply with any agreement. Compare coordination.

- public goods

- Products that are nonexcludable and nonrival in consumption, such as national defense or clean air or water. Compare common-pool resources.

- collective action problems

- Obstacles to cooperation that occur when actors have incentives to collaborate but each acts with the expectation that others will pay the costs of cooperation.

- free ride

- To fail to contribute to a public good while benefiting from the contributions of others.

- iteration

- Repeated interactions with the same partners.

- linkage

- The linking of cooperation on one issue to interactions on a second issue.

- power

- The ability of Actor A to get Actor B to do something that B would otherwise not do; the ability to get the other side to make concessions and to avoid having to make concessions oneself.

- coercion

- A strategy of imposing or threatening to impose costs on other actors in order to induce a change in their behavior.

- outside options

- The alternatives to bargaining with a specific actor.

- agenda setting

- Actions taken before or during bargaining that make the reversion outcome more favorable for one party.

Endnotes

- Robert C. Feenstra and Akira Sasahara, “The ‘China Shock,’ Exports and U.S. Employment: A Global Input–Output Analysis,” Review of International Economics 26, no. 5 (November 2018): 1053–83, https://doi.org/10.1111/roie.12370. Return to reference 6

- On bargaining and cooperating simultaneously, see James D. Fearon, “Bargaining, Enforcement, and International Cooperation,” International Organization 52, no. 2 (1998): 269–305. Return to reference 7

-

On the general forms of cooperation reviewed here, see Arthur A. Stein, “Coordination and Collaboration Regimes in an Anarchic World,” International Organization 36, no. 2 (1982): 299–324; Duncan Snidal, “Coordination versus Prisoners’ Dilemma: Implications for International Cooperation and Regimes,” American Political Science Review 79, no. 4 (December 1985): 923–42; and Lisa L. Martin, “Interests, Power, and Multilateralism,” International Organization 46, no. 4 (1992): 765–92.Return to reference 8

- In fact, the United States and the Soviet Union did sign several arms control agreements, which may have prevented the arms race from being even worse. It was not until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 that serious reductions in nuclear armaments took place. Return to reference 9

- On privileged groups, see Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965). Return to reference 10

- On iteration and international cooperation, see Robert Axelrod, The Evolution of Cooperation (New York: Basic Books, 1984). The trench warfare example mentioned in the following text is described in Chapter 4. Return to reference 11

-

For the expectation of future punishment to induce current cooperation, however, actors must value the future enough that future gains matter. Everyone discounts the future; that is, they value it somewhat less than the present. A dollar today is worth more to us than a dollar next year, and much more than a dollar received in 20 years. The more actors discount the future, the less likely the threat of future punishment will encourage them to cooperate today. Conversely, the more actors value the future, the more likely the threat of future punishment will encourage cooperation now.Return to reference 12

- On the consequences of misperception, see Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Relations (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976). Return to reference 13

- George W. Downs, David M. Rocke, and Randolph M. Siverson, “Arms Race and Cooperation,” in Cooperation under Anarchy, ed. Kenneth Oye (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986): 118–46. Return to reference 14

- Robert A. Dahl, “The Concept of Power,” Systems Research and Behavioral Science 2, no. 3 (July 1957): 201–15. Return to reference 15

- See Michael Barnett and Raymond Duvall, eds., Power in Global Governance (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005). Return to reference 16

- For an analysis of how China used retaliatory tariffs to impose political costs on Trump, see Sung Eun Kim and Yotam Margalit, “Tariffs As Electoral Weapons: The Political Geography of the US–China Trade War.” International Organization 75, no. 1 (2021): 1–38. Return to reference 17

- See, for example, Dan Reiter and Allan C. Stam, Democracies at War (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002). Return to reference 18

- This quotation is often cited, and the exact wording sometimes varies. The original source is Jean Sainteny, L’histoire d’une paix manquée: Indochine, 1945–47 (Paris: Amiot-Dumont, 1953): 231. Return to reference 19

- Yusuf Khan, “China Is Sourcing More of Its Farm Goods from Other Countries, and That’s a Bad Sign for the US,” Business Insider, July 31, 2019, https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/stocks/china-sources-more-farm-goods-brazil-us-trade-war-2019-7-1028403926 (accessed 10/21/20). Return to reference 20

- John W. Kingdon, Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, 2nd ed. (New York: HarperCollins, 1995). Return to reference 21

- Dan Altman, “By Fait Accompli, Not Coercion: How States Wrest Territory from Their Adversaries,” International Studies Quarterly 61, no. 4 (December 2017): 881–91. Return to reference 22