Core Objectives

EXPLAIN the role that religious belief systems played in rebuilding the Islamic world, Europe, and Ming China in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

No region suffered more from the Black Death than western Christendom, and arguably no region made a more spectacular comeback. From 1100 to 1300, Europe had enjoyed a surge in population, rapid economic growth, and significant technological and intellectual innovations, only to see these achievements halted in the fourteenth century by famine and the Black Death. Europeans responded by creating new political and cultural forms. New dynastic states arose, competing with one another, and a movement called the Renaissance revived Europe’s connections with its Greek and Roman past and produced masterpieces of art, architecture, and other forms of thought.

Core Objectives

EXPLAIN the role that religious belief systems played in rebuilding the Islamic world, Europe, and Ming China in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

In the aftermath of famine and plague, the peoples of western Christendom, like those in the Muslim world, looked to their religious beliefs and institutions as foundations for recovery. The faith of many had been severely tested, and religious authorities had to struggle to reclaim their power. To begin with, the late medieval western church found itself divided at the top (at one point during this period there were three popes) and challenged from below, both by individuals pursuing alternative kinds of spirituality and by increasing demands on the clergy and church administration. Disappointment with the clergy smoldered. The peasantry despaired at the absence of clergy when they were so greatly needed during the famines and Black Death. With groups like the Beghards and Beguines challenging the clergy’s right to define religious doctrine and practices, the church fought back, identifying all that was suspect and demanding strict obedience to the true faith. This response included the persecution of Jews, Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula, gays, sex workers, “witches,” and others considered by the church to be heretical. During this period the church also expanded its charitable and bureaucratic functions, providing alms to the urban poor and registering births, deaths, and economic transactions. Crucially, when faced with challenges to its authority, the church associated itself with secular rulers, lending moral authority to kings who claimed to rule “by divine right.”

At the same time, the high death toll of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries emboldened those who survived to seek higher wages or reductions in their feudal obligations. When landlords resisted or kings tried to impose new taxes, there were uprisings, including a 1358 peasant revolt in France that was dubbed the Jacquerie (the term derived from “Jacques Bonhomme,” a name that contemptuous “masters” used for all peasants). Armed with only knives and staves, the peasantry went on a rampage, killing hated nobles and clergy and burning and looting all the property they could get their hands on. At issue was the peasants’ insistence that they should no longer be tied to their land or have to pay for the tools they used in farming.

A better-organized uprising took place in England in 1381. Although the English Peasants’ Revolt began as a protest against a tax levied to raise money for a war on France, it was also fueled by postplague labor shortages: serfs demanded the freedom to move about, and free farmworkers called for higher wages and lower rents. When landlords balked at these demands, aggrieved peasants assembled at the gates of London. The protesters demanded abolition of the feudal order, but the king ruthlessly suppressed them. Nonetheless, in both France and England a free peasantry gradually emerged as labor shortages made it impossible to keep peasants bound to the soil.

Europe’s political rulers aligned themselves with church leaders to rebuild their states and consolidate their power. One royal family, the Habsburgs, drew on their Catholic religious traditions and established a powerful, long-lasting dynasty that would rule large parts of central Europe for centuries to follow. This family provided continuous emperors from 1445 to 1806 for the federation of states known as the Holy Roman Empire, and for a time they ruled Spain and its New World colonies. Yet even at the height of its power in the early sixteenth century, the Habsburg monarchy never succeeded in restoring an integrated empire to western Europe.

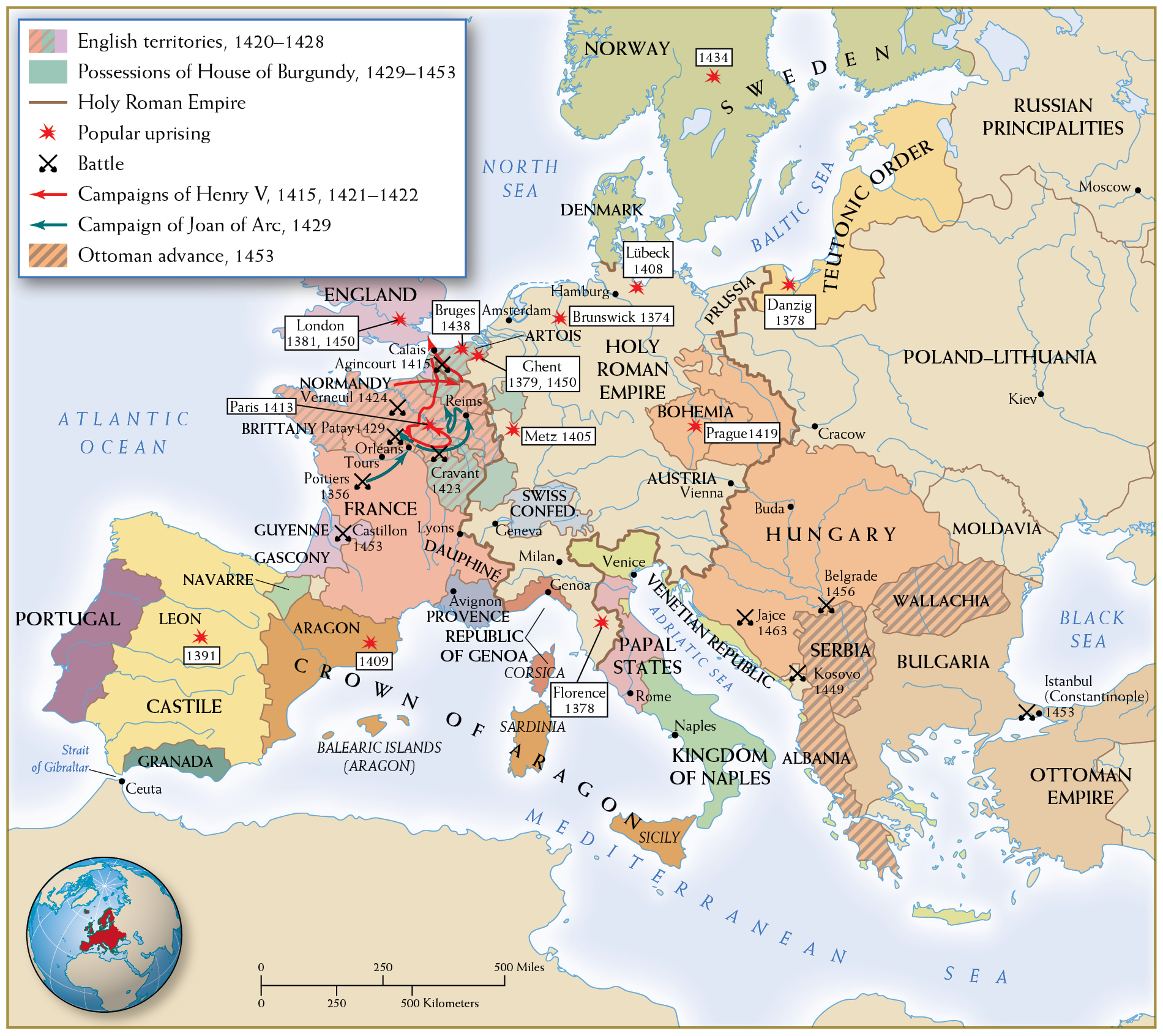

In 1450, western Christendom had no central government, no official tongue, and only a few successful commercial centers, mostly in the Mediterranean basin. (See Map 11.3.) The feudal system of a lord’s control over the peasantry (see Chapter 10), which was now in decline, left a legacy of political fragmentation and enduring elite privileges, which made the consolidation of a unified Christian Europe even more difficult to achieve. Europe’s linguistic diversity reflected its political fragmentation. No single ruler or language united peoples, even when they shared a religion. Europe saw Latin lose ground as rulers chose various regional dialects (such as French, Spanish, or English) to be their official state languages, in contrast with China, whose written literary Chinese script remained a key administrative tool for the new dynasts, and the Islamic world, where Arabic was the common language of faith and Turkish the language of administration.

Those who sought to rule the emerging states faced numerous obstacles. For example, rival claimants to the throne financed threatening private armies. Also, the clergy demanded and received privileges in the form of access to land and relief from taxation; they often meddled in politics, and the church became a formidable economic powerhouse. And once the printing press became more widely available in Europe in the 1460s, printers circulated anonymous pamphlets criticizing the court and the clergy. Some states had consultative political bodies—such as the Estates-General in France, the Cortes in Spain, and Parliament in England—in which princes formally asked representatives of their people for advice and, in the case of the English Parliament, for consent to new forms of taxation. Such political bodies gave no voice to common men and no representation to women. But they did allow the collective expression of grievances against overbearing policies.

Out of the chaos of famine, disease, and warfare, the diverse peoples of Europe found a political way forward. This path involved the formation of centralized dynastic monarchies. While not new to this period, the political institution of monarchy was particularly instrumental to western Christendom in the fifteenth century. Often in competition with the new monarchies, a handful of European city-states, in which a narrow group of wealthy and influential voters selected their leaders, survived right up to the nineteenth century and in some cases into the twentieth. Consolidation of these states occurred sometimes through strategic marriages but more often through warfare, both between princely families and with local aristocratic allies and foreign mercenaries.

One striking example of this political turmoil was the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453), in which the French sought to throw off English domination. The Black Death raged in the early years of this intermittent conflict. A central figure toward the end of the war was the peasant girl Joan of Arc, whose visions of various saints inspired her to support the French monarch Charles VII and see him crowned at Reims Cathedral. While Joan was a charismatic leader of troops, commanding as many as 8,000 at the decisive battle at Orléans, eventually the French nobility turned on her, and she was captured by the English. Joan was tried for heresy and burned at the stake in Rouen in 1431. Joan’s brief, but remarkable, part in the Hundred Years’ War illustrates the role an exceptional woman, even a peasant girl, could play on the predominantly male, elite political stage.

Europe was a region divided by dynastic rivalries during the fifteenth century. Locate the most powerful regional dynasties on the map: Portugal, Castile, Aragon, France, Burgundy, England, and the Holy Roman Empire.

Elsewhere, in southern Europe, where economies rebounded through seaborne trade with Southwest Asia, political stabilization was swifter. The stabilization of Italian city-states such as Venice and Florence, and of monarchical rule in Portugal and Spain, led to an economic and cultural flowering known as the Renaissance. In northern and western Europe, the process took longer. In England and France, in particular, internal feuding, regional warfare, and religious fragmentation delayed recovery for decades (see Chapter 12).

War and overseas trade played a central role in the emergence of new dynasties in Portugal and Spain. Through the fourteenth century, Portuguese Christians devoted themselves to fighting the Moors, who were Muslim occupants of North Africa, the western Sahara, and the Iberian Peninsula. After the Portuguese crossed the Strait of Gibraltar and seized the Moorish fortresses at Ceuta, in Morocco, their ships could sail between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic without Muslim interference. With that threat diminished, the Portuguese perceived their neighbor Castile (a region in what is now Spain) as their chief foe. Under João I (r. 1385–1433), Portugal defeated the Castilians, becoming the dominant power on the Iberian Peninsula. No longer preoccupied with Castilian competition, the Portuguese sought new territories and trading opportunities in the North Atlantic and along the West African coast. João’s son Prince Henrique, known later as Henry the Navigator, further expanded the royal family’s domain by supporting expeditions down the coast of Africa and offshore to the Atlantic islands of Madeira and the Azores. The west and central coasts of Africa and the islands of the North and South Atlantic, including the Cape Verde Islands, São Tomé, Principe, and Fernando Po, soon became Portuguese ports of call.

Portuguese monarchs granted the Atlantic islands to nobles as hereditary possessions on condition that the grantees colonize them, and soon the colonizers were establishing lucrative sugar plantations. In gratitude, noble families and merchants threw their political weight behind the king. Subsequent monarchs continued to cultivate local aristocrats’ support for monarchical authority, thus ensuring smooth succession to the crown for members of the royal family.

In Spain, a new dynasty also emerged, though the road was difficult. Medieval Spain comprised rival kingdoms that quarreled ceaselessly. Within those kingdoms, several religions coexisted: Muslims, Jews, and Christians lived side by side in relative harmony, and Muslim armies still occupied strategic posts in the south. Over time, marriages and the formation of kinship ties among nobles and between royal lineages yielded a new political order. One by one, the major houses of the Spanish kingdoms intermarried, culminating in the wedding of Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon in 1469. This marriage linked Castile, wealthy and populous, to Aragon, which enjoyed an extended trading network in the Mediterranean. Together, the monarchs brought unruly nobles and distant towns under their control. They topped off their achievements by marrying their children into other European royal families—especially the Habsburgs, central Europe’s most powerful dynasty. Thus, Spain’s two most important provinces were joined, and Spain later became a state to be reckoned with.

The new Spanish rulers sent Christian armies south to push Muslim forces out of the Iberian Peninsula. By the mid-fifteenth century, only Granada, a strategic linchpin overlooking the straits between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, remained in Muslim hands. After a long and costly siege, Christian forces captured the fortress there in 1492. This was a victory of enormous symbolic importance, as joyous as the fall of Constantinople to Mehmed and the Ottomans in 1453 was depressing (for Christians).

The Inquisition and Westward Exploration Isabella and Ferdinand sought to drive all non-Catholics out of Spain. Terrified by Ottoman incursions into Europe, they launched the Inquisition in 1481, taking aim especially against conversos—converted Jews and Muslims, whom they suspected were Christians only in name. When Granada fell, the crown ordered the expulsion of all Jews from Spain. After 1499, a more tolerant attempt to convert the Moors (Muslims) by persuasion gave way to forced conversion—or emigration. All told, almost half a million people were forced to flee the Spanish kingdoms. This lack of tolerance meant that Spain, like other European states in this era, became increasingly homogeneous. With fewer groups vying for influence within their territories, rulers’ attention turned outward, fueling rivalries between the various European states.

So strong was the tide of Spanish fervor by late 1491 that the monarchs listened now to a Genoese navigator whose pleas for patronage they had previously rejected. Christopher Columbus promised them unimaginable riches that could finance their military campaigns and bankroll a crusade to liberate Jerusalem from Muslim hands. Off he sailed with a royal patent that guaranteed the monarchs a share of all he discovered. Soon the Spanish economy was reorienting itself toward the Atlantic, and Spain’s merchants, missionaries, and soldiers were preparing for conquest and profiteering in what the Spanish had perceived, just a few years before, as a blank space on the map.

Just as the Ming invoked Han Chinese traditions and the Ottomans looked to Sunni Islam to point the way forward, European elites drew on their own traditions for guidance as they rebuilt after the devastation of the plague. They found inspiration in ancient Greek and Roman institutions and ideas. Europe’s extraordinary political and economic revival also involved a powerful outpouring of cultural achievements, led by Italian scholars and artists and financed by bankers, churchmen, and nobles. Much later, scholars coined the word Renaissance (“rebirth”) to characterize the cultural flourishing of the Italian city-states, France, the Netherlands, England, and the Holy Roman Empire in the period 1430–1550. What was being “reborn” was ancient Greek and Roman art and learning—knowledge that could help people understand an expanding world and support the rights of secular individuals to exert power in it.

Although Christians generally portrayed the “fall” of Constantinople as a calamity, in fact the Muslim conquest brought benefits to western Europe. Many Christian survivors fled to ports in the west, bringing with them classical and Arabic manuscripts previously unknown in Europe. The well-educated, Greek-speaking émigrés generally became teachers and translators, thereby helping to revive Europeans’ interest in classical antiquity and spreading knowledge of ancient Greek (which had virtually died out in medieval times). These manuscripts and teachers would play a vital role in Europe’s Renaissance.

Although the Renaissance was largely funded by popes, Christian kings, and powerful wealthy merchants, it challenged the authority of traditional religious elites, breaking the medieval church’s monopoly on answers to the big questions. Religious topics and themes, such as David and Goliath, Judith and Holofernes, and various scenes from Jesus’s story (the annunciation of his birth to Mary, Jesus’s adoration by the magi, and his baptism and crucifixion), dominated much of Renaissance art, but these themes took on new meaning as warnings to overbearing rulers and reminders to the obscenely wealthy, who sponsored many of these works, of their place in the cosmos and the civic responsibility that stemmed from their wealth. These religious themes were also joined by classical topics, such as scenes from mythology and the ancient past. The movement valued secular forms of learning, rather than just Christian doctrine, and a more human-centered understanding of the cosmos.

Core Objectives

EXAMINE the way art and architecture reflected the political realities of the Islamic world, Europe, and Ming China after the Black Death.

The Renaissance was all about new exposure to the old—to classical texts and ancient art and architectural forms. Although some Greek and Roman texts were known in Europe and the Islamic world, the use of the printing press made others accessible to western scholars for the first time. Scholars now realized that the pre-Christian Greeks and Romans had developed powerful means of representing and caring for the human body. Having studied the world directly, without the need to square their observations with biblical information, the ancients had much to teach about geography, astronomy, and architecture and about how to govern states and armies. For Renaissance scholars it was no longer enough to understand Christian doctrine and to concern themselves with the next world. One had to go back to the original, classical sources in order to understand the human condition. This in turn required the learning of languages and history. Scholarship that attempted to return to Greek and Roman sources became known as humanism.

Because political and religious powers were not united in Europe (as they were in China and the Islamic world), scholars and artists seeking sponsors for their work could play one side against the other or, alternatively, could suffer both clerical and political persecution. Michelangelo, a leading painter, sculptor, architect, and engineer of the age, completed commissions for the famous Florentine bankers and political leaders of the Medici family, for the Florentine Wool Guild, and for Pope Julius II. Peter Paul Rubens painted for the courts of France, Spain, England, and the Netherlands, as well as selling paintings on the open market. These two painters, renowned for showing a great deal of flesh, frequently offended conservative church officials. Even so, most support for the arts came either from the church or from individual clergymen, and virtually all secular donors were devout believers who commissioned works with religious themes. The Dutch scholar Desiderius Erasmus ridiculed corrupt popes and the clergy under the patronage of English, Dutch, and French supporters while remaining a Catholic, an ordained cleric, and an opponent of Reformation doctrines. Conflicts within the Catholic Church, between the church and secular leaders, and among secular leaders and wealthy private citizens enabled artists to present challenging images and ideas with an unusual independence.

Gradually, a network of educated men and women took shape that was not wholly dependent on the church, the state, or a single princely patron. Classical knowledge gave individuals the means to challenge political, clerical, and aesthetic authority. Moreover, rivalries between Europe’s relatively small states and city-states allowed many of these scholars to dodge the authorities by fleeing to neighboring communities. Of course, they could also use their learning to defend the older elites: for example, numerous lawyers and scholars continued to work for the popes in defending the papacy. At the same time, men like Erasmus and later Martin Luther (the leading figure of the Reformation in the sixteenth century) looked to secular princes to support their critical scholarship. In Florence, Niccolò Machiavelli wrote the most famous treatise on authoritarian power, The Prince (1513). Machiavelli argued that political leadership required mastering the rules of modern statecraft, even if in some cases this meant disregarding moral imperatives. Holding and exercising power were vital ends in themselves, he claimed; traditional ideas of civic virtue should not deter rulers, like those of the Medici family, from maintaining control over society.

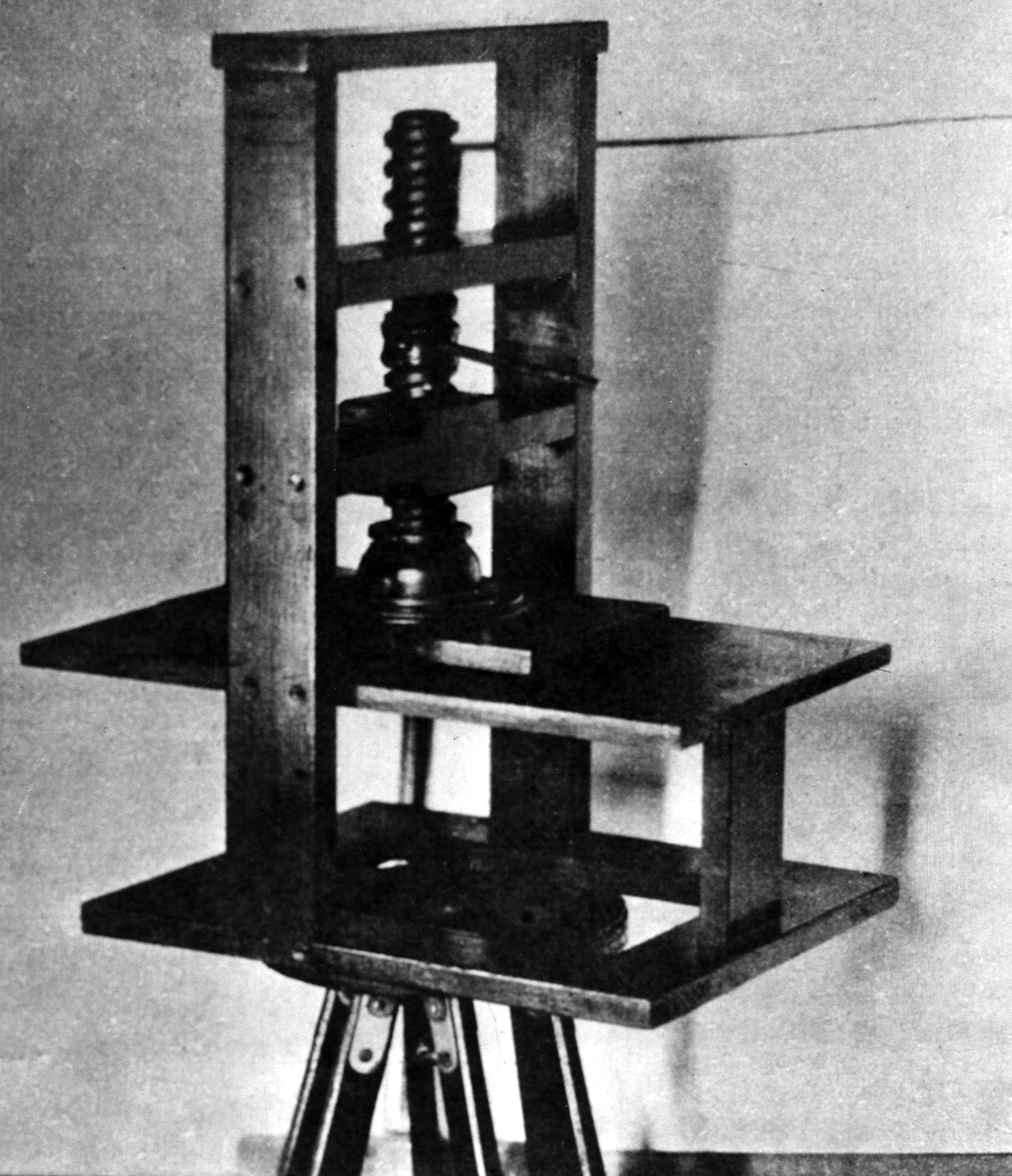

The Printing Press Over time one major technological advance, the invention of the printing press, would serve to increase the spread of knowledge more than any other phenomenon. The earliest advances in printing were made in China, where wood block printing first appeared around 220 CE, followed by movable type around 1040, and then the first metal movable type was used in Korea around 1300. In the 1450s, Johannes Gutenberg, the son of a German goldsmith, applied a technology to printing that was similar to the technology used to stamp metal coins. The first printed newspapers, leaflets, pamphlets, and books were printed on large wood frame presses that used rows of movable type to stamp the ink on the printed pages. Now hundreds of copies could be made in a few hours, hundreds of hours faster than handwritten and hand-bound copies of books could be produced. A second key factor that made this communication revolution possible was readily available cheap paper, made from old rags turned into pulp at local mills. Rising literacy rates, which increased the demand for books, were a third factor.

Artistic and intellectual experiments, specifications for innovative weapons, and humanist writings were rapidly exported from Renaissance Italy to other parts of Europe. Major news like Columbus’s first voyage and the resulting encounters and conquests spread rapidly around Europe, as did major criticisms of this new form of European imperialism. Rulers also used this revolution in communication to expand and centralize their own power through widely distributed printed propaganda and the creation of standardized national languages. The powerful impact of printing was immediate, and its role in communication would continue to grow and evolve for the centuries ahead both in Europe and globally.

With Renaissance ideas challenging traditional authority and rulers facing a range of internal and external obstacles, the new monarchies of Europe were not all immediately successful in consolidating power and unifying peoples. In France and England, for example, the great age of monarchy had yet to dawn. Even when stable states did arise in Europe, they were fairly small compared with the Ottoman and Ming Empires. In the mid-sixteenth century, Portugal and Spain, Europe’s two most expansionist states, had populations of 1 million and 9 million, respectively. England, excluding Wales, had a mere 3 million in 1550. Only France, with 17 million, had a population close to the Ottoman Empire’s 25 million. And these numbers paled in comparison with Ming China’s population of nearly 200 million in 1550 and Mughal India’s 110 million in 1600. But in Europe, small could be advantageous. Portugal’s relatively small population meant that the crown had fewer groups to control. In the world of finance, the most successful merchants were those inhabiting the smaller Italian city-states and, a bit later, the cities of the northern Netherlands. The Florentines developed sophisticated banking techniques, created extensive networks of agents throughout Europe and the Mediterranean, and served as bankers to the popes. At the same time, the Renaissance—which flourished in the city-states and newly stabilized monarchies—made elite European culture more cosmopolitan and independent from government authority, even if it could not unify the states and peoples who cultivated it.