10Becoming “The World”

1000–1300 CE

Core Objectives

- IDENTIFY technological advances of this period, especially in ship design and navigation, and EXPLAIN how they facilitated the expansion of Afro-Eurasian trade.

- DESCRIBE the varied social and political forces that shaped the Islamic world, India, China, and Europe, and EVALUATE the degree to which these forces integrated cultures and geographic areas.

- COMPARE the internal integration and external interactions of sub-Saharan Africa with those of the Americas, and with the connected Eurasian world.

- ASSESS the impacts that the Mongol Empire had on Afro-Eurasian peoples and places.

In the late 1270s two Nestorian Christian monks, Bar Sāwmā and Markōs, voyaged from the court of the Mongol leader Kublai Khan in what is now Beijing into the heart of the Islamic world and beyond. They were not Europeans. They were Uighurs, a Turkish people of central Asia, many of whom had converted to Christianity centuries earlier. The monks hoped to make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in order to visit the tombs of the martyrs enshrined there and along the way.

On their journey westward, Bar Sāwmā and Markōs traveled a world bound together by economic and cultural exchange. The two monks lingered at the magnificent trading hub of Kashgar in what is now western China, where caravan routes converged in a market for jade, exotic spices, and precious silks. Unable to continue on to Jerusalem due to the route’s dangers (including murderous robbers), the monks parted ways at Baghdad. Later, in 1287, Bar Sāwmā was appointed an ambassador by the Buddhist Mongol il-Khan of Persia, Arghūn, to drum up support among European leaders for an attack on Jerusalem to wrest it from Muslim control. He visited Constantinople (where the Byzantine emperor gave him gold and silver), Rome (where he met with the pope at the shrine of Saint Peter), Paris (where he saw that city’s vibrant university), and Bordeaux (where he was welcomed by the English king, Edward I). In the end, neither monk ever reached Jerusalem or returned to China. Bar Sāwmā ended his days in Baghdad, and Markōs became patriarch of the Nestorian branch of Christianity, centered in modern-day Iran. Yet their voyages exemplified the crisscrossing of people, money, goods, and ideas along the trade routes and sea-lanes that connected the world’s regions.

Three related themes dominate the period from 1000 to 1300 CE, at the end of which a monk like Bar Sāwmā could make such a journey. First, trade along sea-based routes increased and coastal trading cities began to expand dramatically. Second, greater trade and religious integration generated the world’s four major cultural “spheres,” whose inhabitants were linked by shared institutions and beliefs: the Islamic world, India, China, and Europe. Sub-Saharan Africa and the Americas also thrived during this period; however, they remained more fragmented, experiencing more limited political and economic integration. Third, the Mongol Empire, stretching from China to Persia and as far as eastern Europe, ruled over huge swaths of land in many of the world’s major cultural spheres. Each of these three themes contributes to an understanding of how Afro-Eurasia became a “world” unified through trade, migration, and even religious conflict.

Global Storyline

The Emergence of the World We Know Today

- Advances in maritime technology lead to increased sea trade, transforming coastal cities into global trading hubs and elevating Afro-Eurasian trade to unprecedented levels.

- Intensified trade and religious integration shape four major cultural “spheres”: the Islamic world, India, China, and Europe.

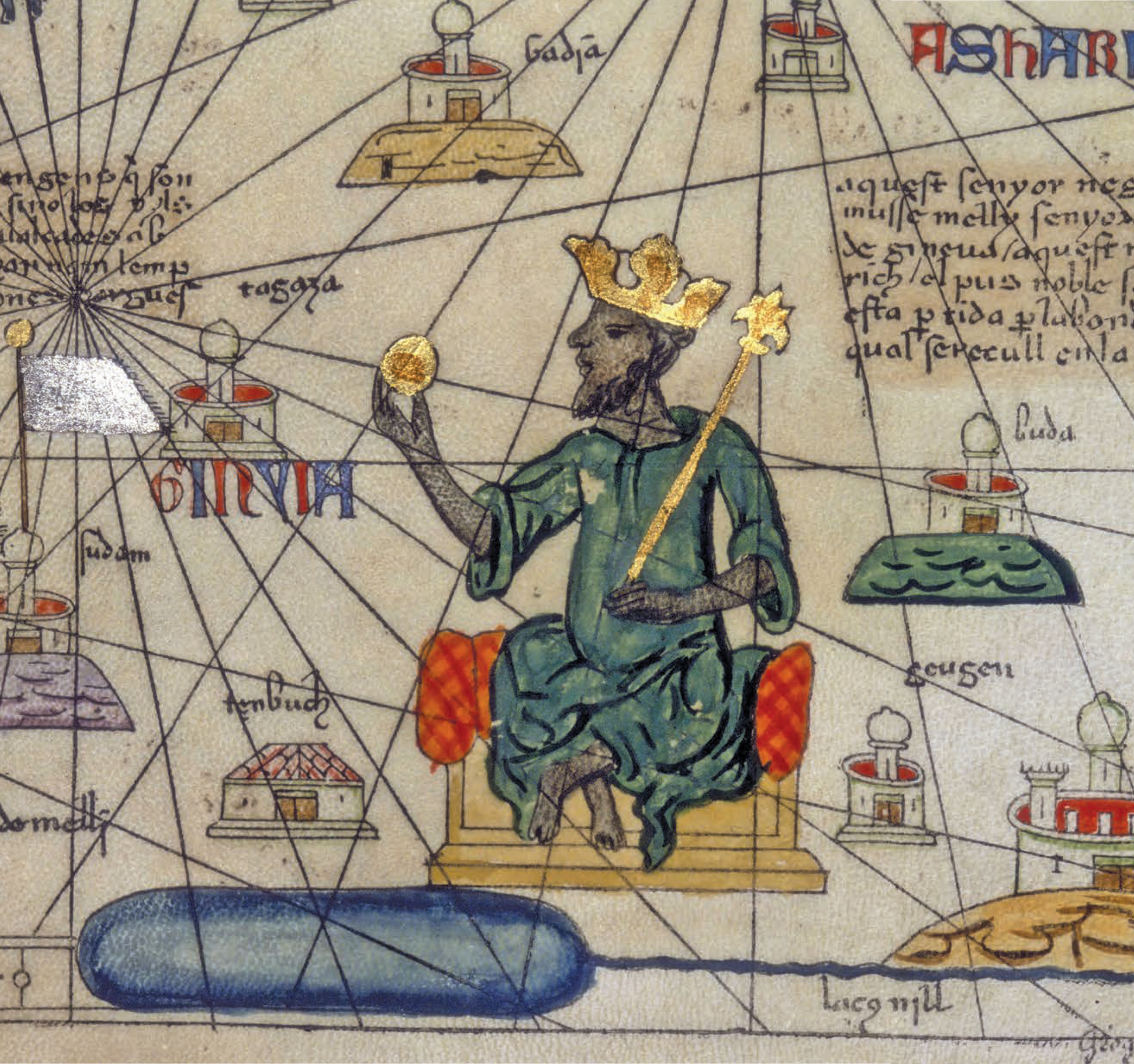

- Sub-Saharan Africa is drawn into Eurasian exchange, resulting in a true Afro-Eurasia–wide network, while the Americas experience more limited political, economic, and cultural integration.

- The Mongol Empire integrates many of the world’s major cultural spheres.