Why Compare China and Rome?

Conclusion

Han dynasty China and Rome both constructed empires of unprecedented scale and duration, yet they differed in fundamental ways. Starting out with a less numerous and less dense population than China, Rome relied on enslaved people and “barbarian” immigrants to expand and diversify its workforce. While less than 1 percent of the Chinese population was enslaved, more than 10 percent of the population in the Roman Empire was enslaved. The Chinese rural economy was built on a huge population of free peasant farmers; this enormous labor pool, together with a remarkable bureaucracy, enabled the Han to achieve great political stability. In contrast, the millions of peasant farmers who formed the backbone of rural society in the Roman Empire were much more loosely integrated into the state structure. They never unified to revolt against their government and overthrow it, as did the mass peasant movements of Later (Eastern) Han China. In comparison with their counterparts in Han China, the peasants in the Roman Empire were not as well connected because they lived farther apart from one another, and they were not as united in purpose. Here, too, the Mediterranean environment accented separation and difference.

In contrast with the elaborate Confucian bureaucracy in Han China, the Roman Empire was relatively fragmented and under-administered. Moreover, no single philosophy or religion ever underpinned the Roman state in the way that Confucianism buttressed the dynasties of China. Both empires, however, benefited from the spread of a uniform language and imperial culture. The process was more comprehensive in China, which possessed a single language that the elites used, than in Rome, where officially a two-language world existed: Latin in the western Mediterranean, Greek in the east. Both states fostered a common imperial culture across all levels of society. Once entrenched, these cultures and languages lasted well after the end of empire.

Differences in human resources, languages, and ideas led the Roman and Han states to evolve in unique ways. In both places, however, faiths that filtered in from the margins—Christianity and Buddhism—eclipsed the classical and secular traditions that grounded the states’ foundational ideals. Expanded communication networks accelerated the transmission of these new faiths. The new religions added to the cultural mix that outlasted the Roman Empire and the Han dynasty.

At their height, both states surpassed their forebears by translating unprecedented military power into the fullest form of state-based organization. Each state’s complex organization involved the systematic control, counting, and taxing of its population. In both cases, the general increase of the population, the growth of huge cities, and the success of long-distance trade contributed to the new scales of magnitude, making these states the world’s first two long-lasting global empires. The Han were not superseded in East Asia as the model empire until the Tang dynasty in the seventh century CE. In western Afro-Eurasia, the Roman Empire was not surpassed in scale or intensity of development until the rise of powerful European nation-states more than a millennium later.

After You Read This Chapter

Go to  to see what you’ve learned—and learn what you’ve missed—with personalized feedback along the way.

to see what you’ve learned—and learn what you’ve missed—with personalized feedback along the way.

TRACING THE GLOBAL STORYLINE

FOCUS ON: Comparing the Han and Roman Empires

- Han China and imperial Rome assimilate diverse peoples and regard outsiders as uncivilized.

- Both empires develop professional military elites, codify laws, and value the role of the state (not just the ruler) in supporting their societies.

- Both empires serve as models for successor states in their regions.

- The empires differ in their ideals and the officials they value: Han China values civilian bureaucrats and magistrates; Rome values soldiers and military governors.

KEY TERMS

THINKING ABOUT GLOBAL CONNECTIONS

- Thinking about Worlds Together, Worlds Apart and Globalizing Empires In the six centuries between 300 BCE and 300 CE, the Han dynasty and imperial Rome united huge populations and immense swaths of territory not only under their direct control but also under their indirect influence. In what ways did this expansive unity at each end of Afro-Eurasia have an impact on the connections between these two empires? In what ways did these two empires remain worlds apart?

- Thinking about Changing Power Relationships and Globalizing Empires Both the Han dynasty and the Roman Empire developed new models for heightened authoritarian control placed in the hands of a single ruler. In what ways did this authoritarian control at the top shape power relationships at all levels of these two societies? What were some potential challenges to this patriarchal, centralized control?

- Thinking about Transformation & Conflict and Globalizing Empires Both the Han dynasty and the Roman Empire faced intense threats along their borders. In what ways did Han interactions with nomadic groups like the Xiongnu and Roman interactions with Parthians to the east and Germans and Goths to the north affect these globalizing empires? In what ways were the experiences of the subjugated peoples similar and different in both empires?

More information

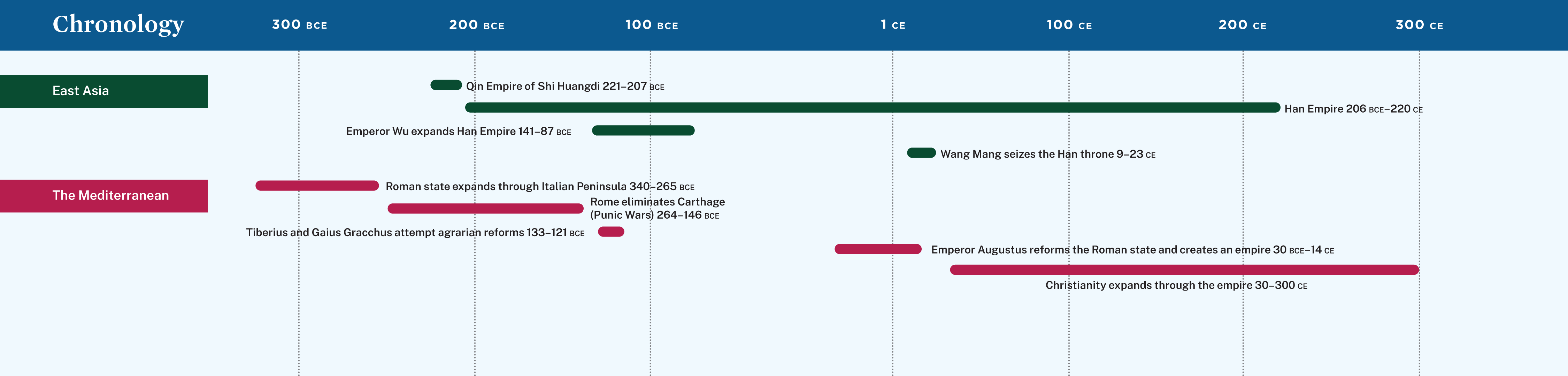

A timeline showing events from 300 B C E to 300 C E. The timeline shows various events represented by diamonds and lines color coded by region of the world that are situated between and around lines representing 300 B C E, 200 B C E, 100 B C E, 1 C E, 100 C E, 200 C E, and 300 C E. In East Asia, the Qin Empire of Shi Huangdi is placed at 221 to 207 B C E, the Han Empire is placed at 206 B C E to 220 C E, Emperor Wu expanding the Han Empire is placed at 141 to 87 B C E, and Wang Ming seizing the Han throne is place at 9 to 23 C E. In the Mediterranean, the Roman state expanding through the Italian Peninsula is placed at 340 to 265 B C E, Rome eliminating Carthage in the Punic Wars is placed at 264 to 146 B C E, and Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus attempting agrarian reforms is placed at 133 to 121 B C E. Emperor Augustus reforming the Roman state and creating an empire is placed at 30 B C E to 14 C E and Christianity expanding through the empire is placed at 30 to 200 C E.

Glossary

- Augustus

- Latin term meaning “the Revered One”; title granted by the Senate to the Roman ruler Octavian in 27 BCE to signify his unique political position. Along with his adopted family name, Caesar, the military honorific imperator, and the senatorial term princeps, Augustus became a generic term for a leader of the Roman Empire.

- Christianity

- New religious movement originating in the Eastern Roman Empire in the first century CE, with roots in Judaism and resonance with various Greco-Roman religious traditions. The central figure, Jesus, was tried and executed by Roman authorities, and his followers believed he rose from the dead. The tradition was spread across the Mediterranean by his followers, and Christians were initially persecuted—to varying degrees—by Roman authorities. The religion was eventually legalized in 312 CE, and by the late fourth century CE it became the official state religion of the Roman Empire.

- commanderies

- The thirty-six provinces (jun) into which Shi Huangdi divided territories. Each commandery had a civil governor, a military governor, and an imperial inspector.

- Emperor Wu

- (r. 141–87 BCE) Also known as Emperor Han Wudi, or the “Martial Emperor”; the ruler of the Han dynasty for more than fifty years, during which he expanded the empire through his extensive military campaigns.

- globalizing empires

- Empires that cover immense territory; exert significant influence beyond their borders; include large, diverse populations; and work to integrate conquered peoples.

- Imperial University

- Institution founded in 136 BCE by Emperor Wu (Han Wudi) not only to train future bureaucrats in the Confucian classics but also to foster scientific advances in other fields.

- Pax Romana

- Latin term for “Roman Peace,” referring to the period from 25 BCE to 235 CE, when conditions in the Roman Empire were relatively settled and peaceful, allowing trade and the economy to thrive.

- Pax Sinica

- Modern term (paralleling the term Pax Romana) for the “Chinese Peace” that lasted from 149 to 87 BCE, a period when agriculture and commerce flourished, fueling the expansion of cities and the growth of the population of Han China.

- Punic Wars

- Series of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage from 264 to 146 BCE that resulted in the end of Carthaginian hegemony in the western Mediterranean, the growth of Roman military might (army and navy), and the beginning of Rome’s aggressive foreign imperialism.

- res publica

- Term (meaning “public thing”) used by Romans to describe their Republic, which was advised by a Senate and was governed by popular assemblies of free adult males, who were arranged into voting units, based on wealth and social status, to elect officers and legislate.

- Shi Huangdi

- Title taken by King Zheng in 221 BCE, when he claimed the mandate of heaven and consolidated the Qin dynasty. He is known for his tight centralization of power, including standardizing weights, measures, and writing; constructing roads, canals, and the beginnings of the Great Wall; and preparing a massive tomb for himself filled with an army of terra-cotta warriors.