After You Read This Chapter

Go to  to see what you’ve learned—and learn what you’ve missed—with personalized feedback along the way.

to see what you’ve learned—and learn what you’ve missed—with personalized feedback along the way.

The dying and devastation that came with the Black Death caused many transformations, but certain underlying ideals and institutions endured. What changed were mainly the political regimes; they took the blame for the catastrophes wrought by disease. The Yuan dynasty collapsed, and regimes in the Muslim world and western Christendom were replaced by new political forms. And yet, universal religions and wide-ranging cultural systems endured. A fervent form of Sunni Islam found its champion in the Ottoman Empire. In Europe, centralizing monarchies appeared in Spain, Portugal, France, and England. The Ming dynasts in China set the stage for a long tenure by claiming the mandate of heaven and stressing China’s place at the center of the universe.

Despite these parallels, the new states and empires demonstrated notable differences. These differences were evident in the ambition of a Ming warlord who established a new dynasty, the military expansionism of Turkish warrior bands bordering the Byzantine Empire, and the desire of various European rulers to consolidate power. But interactions among peoples also mattered; this era saw an eagerness to reestablish and expand trade networks and a desire to convert unbelievers to “the true faith”—be it a form of Islam or an exclusive Christianity.

All the dynasties surveyed in this chapter faced similar problems. They had to establish legitimacy with their populations, ensure smooth successions into the future, deal with religious movements, and forge working relationships with nobles, townspeople, merchants, and peasants. Yet each state developed a distinctive identity. They all combined political innovation, traditional ways of ruling, and ideas borrowed from neighbors. European monarchies achieved significant internal unity, often through warfare and in the context of a cultural Renaissance, made possible at least in part with the printing press. Ottoman rulers perfected techniques for ruling an ethnically and religiously diverse empire: they moved military forces swiftly, allowed local communities a degree of autonomy, and trained a bureaucracy dedicated to the Ottoman and Sunni way of life. The Ming fashioned an imperial system based on a Confucian bureaucracy and intense subordination to the emperor so that they could manage a mammoth population with some consistency. The rising monarchies of Europe and the Ottoman state all blazed with religious fervor and sought to eradicate or subordinate the beliefs of other groups.

The new states displayed unprecedented political and economic powers. All demonstrated military prowess, a desire for stable political and social hierarchies and secure borders, and a drive to expand. Each legitimized its rule via dynastic marriage and succession, state-sanctioned religion, and administrative bureaucracies. Each supported vigorous commercial activity. The Islamic regimes, especially, engaged in long-distance commerce and, by conquest and conversion, extended their holdings.

For western Christendom, the Ottoman conquests were decisive. They provoked Europeans to establish commercial connections to the east, south, and west. The consequences of their new toeholds would be momentous—just as the Chinese decision to turn away from overseas exploration and commerce meant that China’s contact with the outside world would be overland and more limited. As we shall see in Chapter 12, both decisions were instrumental in determining which worlds would come together and which would remain apart.

Go to  to see what you’ve learned—and learn what you’ve missed—with personalized feedback along the way.

to see what you’ve learned—and learn what you’ve missed—with personalized feedback along the way.

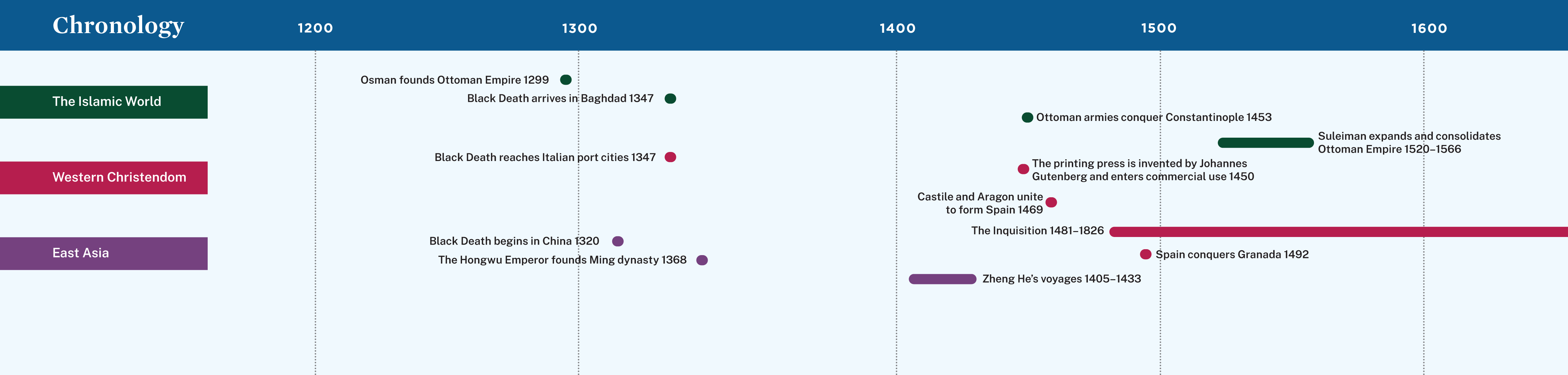

A timeline showing events from circa 1200 to 1600. The timeline shows various events represented by diamonds and lines color coded by region of the world that are situated between and around lines representing 1200, 1300, 1400, 1500, and 1600. In the Islamic world, Osman founds the Ottoman Empire in 1299, the Black Death arrives in Baghdad in 1347, Ottoman armies conquer Constantinople in 1453, and Suleiman expands and consolidates the Ottoman Empire in 1520 to 1566. In Western Christendom, the Black Death reaches Italian port cities in 1347, the printing press is invented by Johannes Gutenberg and enters commercial use in 1450, and Castile and Aragon unite to form Spain in 1469. The Inquisition is placed at 1481 to 1826 and Spain conquers Granada in 1492. In East Asia, the Black Death begins in China in 1320, the Hongwu Emperor founds Ming dynasty in 1368, and Zheng He’s voyages are placed in 1405 to 1433.