![]() How Old Is the Earth?

How Old Is the Earth?

PRECURSORS TO MODERN HUMANS

The modern scientific creation narrative of human evolution would have been unimaginable even just over a century ago, when Charles Darwin was formulating his ideas about human origins. As we will see in this section, scientific discoveries have shown that modern humans evolved from earlier hominins, such as Australopithecus africanus (Taung child) and afarensis (Lucy), as well as from others in the genus Homo, such as Homo habilis, erectus, neanderthalensis, and naledi. Through adaptation to their environment, various species of hominins developed new physical characteristics and distinctive skills. Millions of years after the first hominins appeared, the first modern humans—Homo sapiens—emerged and spread out across the globe.

Evolutionary Findings and Research Methods

Revisions in the time frame of the universe and human existence have occurred over a long period of time. Geologists made early breakthroughs in the eighteenth century when their research into the layers of the earth’s surface revealed a world much older than biblical time implied. Evolutionary biologists, most notably Charles Darwin (1809–1882), concluded that all life had evolved over long periods from simple forms of matter. In the twentieth century, astronomers, evolutionary biologists, climatologists, and archaeologists have employed sophisticated dating techniques to pinpoint the chronology of the universe’s creation, the evolution of all forms of life on earth, and the decisive role that changes in climate have played in the evolution of living forms. And in the early twenty-first century, paleogenomic researchers are recovering full genomic sequences of extinct hominins (such as the Neanderthals) and using ancient DNA to reconstruct the full skeletons of human ancestors (such as the Denisovans) of whom only a few bones have survived.

Understanding the sweep of human history, calculated in millions of years, requires us to revise our sense of time (see Current Trends in World History: Using Big History and Science to Understand Human Origins). A mere century ago, who would have accepted the idea that the universe came into being 13.8 billion years ago, that the earth appeared about 4.5 billion years ago, and that the earliest life forms began to exist about 3.8 billion years ago?

Yet, modern science suggests that human beings are part of a long evolutionary chain stretching from microscopic bacteria to African apes that appeared about 23 million years ago, and that Africa’s “great ape” population separated into several distinct groups of hominids: one becoming present-day gorillas; another becoming chimpanzees; and a third group becoming modern humans only after following a long and complicated evolutionary process. Our focus will be on the third group of hominids, namely the hominins who became modern humans (Homo sapiens) after differentiating ourselves from others in the genera Australopithecus and Ardipithecus, as well as from the now-extinct members of our own Homo genus (namely homo habilis, erectus, neanderthalensis, and naledi; the Denisovans; and many others). A combination of traits, evolving over several million years, distinguished different hominins from other hominids, including (1) lifting the torso and walking on two legs (bipedalism), thereby freeing hands and arms to carry objects and hurl weapons; (2) controlling and then making fire; (3) fashioning and using tools; (4) developing cognitive skills and an enlarged brain and therefore the capacity for language; and (5) acquiring a consciousness of “self.” All these traits were in place at least 150,000 years ago.

Two terms central to understanding any discussion of hominin development are evolution and natural selection. Evolution is the process by which species of plants and animals change and develop over generations, as certain traits are favored in reproduction. The process of evolution is driven by a mechanism called natural selection, in which members of a species with certain randomly occurring traits that are useful for environmental or other reasons survive and reproduce with greater success than those without the traits. Thus, biological evolution (human or otherwise) does not imply progress to higher forms of life, but instead implies successful adaptation to environmental surroundings.

Early Hominins, Adaptation, and Climate Change

![]() Skulls, Tools, and Fire

Skulls, Tools, and Fire

It was once thought that evolution is a gradual and steady process. The consensus now is that evolutionary changes occur in punctuated bursts after long periods of stasis, or non-change. These transformative changes were often brought on, especially during early human development, by dramatic alterations in climate and by ruptures of the earth’s crust caused by the movement of tectonic plates below the earth’s surface. The heaving and decline of the earth’s surface led to significant changes in climate and in animal and plant life. Also, across millions of years, the earth’s climate was affected by slight variations in the earth’s orbit, the tilt of the earth’s axis, and the earth’s wobbling on its axis.

As the earth experienced these significant changes, what was it like to be a hominin in the millions of years before the emergence of modern humans? An early clue came from a discovery made in 1924 at Taung, not far from the present-day city of Johannesburg, South Africa. Raymond Dart, a twenty-nine-year-old Australian anatomist teaching at the Witwatersrand University Medical School, happened upon a skull and bones that appeared to be partly human and partly ape. Believing the creature to be “an extinct race of apes intermediate between living anthropoids (apes) and man . . . a man-like ape,” Dart labeled the creature the “Southern Ape of Africa,” or Australopithecus africanus (Meredith, p. 61). This individual, who came to be known as “Taung child,” had a brain capacity of approximately 1 pint, or a little less than one-third that of a modern man and about the same as that of modern-day African apes. Yet, according to Dart, these australopithecines were different from other animals, for they walked on two legs.

The fact that australopithecines survived at all for about 3 million years in a hostile environment is remarkable. But they did, and over the several million years of their existence in Africa, the genus of australopithecines in the hominin family developed into more than six species. (A species is a group of animals or plants possessing one or more distinctive characteristics.) It is important to emphasize that these australopithecines were not humans but they carried the genetic and biological material out of which modern humans would later emerge.

CURRENT TRENDS IN WORLD HISTORY

Using Big History and Science to Understand Human Origins

The history profession has undergone transformative changes since the end of World War II. One of the most radical changes in historical narratives is what historian David Christian has called “Big History.” Just what it is still remains a mystery for many historians, and few departments of history offer courses in Big History. But Big History presents a coherent narrative of the origins of the universe up to the present. Its influence on our sense of who we are and where we came from is impressive.

Big History covers the history of our universe from its creation 13.8 billion years ago to the present. (See the table in Analyzing Global Developments: The Age of the Universe and Human Evolution.) Because it merges natural history with human history, its study requires knowledge of many fields of science. Big History’s use of the sciences enables us to learn of the universe before our solar system (astrophysics), our planet before life (geology), life before humans (biology), and humans before written sources (paleoanthropology). At present, few historians feel comfortable using these findings or integrating these data into their own general history courses. Nevertheless, Big History provides another narrative of how and when our universe, and we as human beings, came into existence.

Most of this chapter deals with how our species, Homo sapiens, came into being, and here, too, scholars are dependent on a range of approaches, including the work of linguists, biologists, paleoanthropologists, archaeologists, geneticists, and many others. The first major advance in the study of the time before written records occurred in the mid-twentieth century, and it involved the use of radiocarbon dating. All living things contain the radiocarbon isotope C14, which plants acquire directly from the atmosphere and animals acquire indirectly when they consume plants or other animals. When these living things die, the C14 isotope begins to decay into a stable nonradioactive element, C12. Because the rate of decay is regular and measurable, it is possible to determine the age of fossils that leave organic remains for up to 40,000 years.

The evidence for human evolution, discussed in this chapter, requires dating methods that can extend back much farther than radiocarbon dating. Using the potassium-argon method, scientists can calculate the age of nonliving objects by measuring the ratio of potassium to argon in them, since potassium decays into argon. This method allows scientists to calculate the age of objects up to a million years old. Likewise, scientists can use uranium-thorium dating to determine the date of objects (like shells, teeth, and bones) more closely linked to living beings. This uranium-series method permits scientists to date objects up to 500,000 years old. A similar date limit can be reached through thermoluminescence methods applied to soil deposits and objects with crystalline materials that have been exposed to sunlight or heat (as in the flames of a fire pit or the heat of a kiln). Even if a scientist cannot offer a direct date for an object—teeth, skull, or other bone—such methods offer a date for the sediments in which researchers find fossils, as a gauge of the age of the fossils themselves.

As this chapter demonstrates, the environment, especially climate, played a major role in the appearance of hominids and the eventual dominance of Homo sapiens. But how do we know so much about the world’s climate so far back in time? This brings us to yet another scientific breakthrough, known as marine isotope stages. By exploring the marine life, mainly pollen and plankton, deposited in deep seabeds and measuring the levels of oxygen-16 and oxygen-18 isotopes in these life forms, oceanographers and climatologists are able to determine the temperature of the world hundreds of thousands and even millions of years ago and thus to chart the cooling and warming cycles of the earth’s climate.

DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) analysis is another crucial tool for unraveling the beginnings of modern humans. DNA, which determines biological inheritances, exists in two places within the cells of all living organisms—including the human body. Nuclear DNA (nDNA) and mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) exist in males and females, but only mitochondrial DNA from females passes to their offspring, as the females’ egg cells carry their mitochondria with their DNA to the offspring. By examining mitochondrial DNA, researchers can measure genetic relatedness and variation among living organisms—including human beings. Such analysis has enabled researchers to pinpoint human descent from an original African population and to determine various branches of Homo sapiens lineage.

Ancient DNA (aDNA) is opening up new avenues for research on early human ancestors. Paleogeneticists can use aDNA to reconstruct physical traits of long extinct human ancestors for whom only a skull, or jaw, or finger bone may have been found. Teams of scientists, perhaps most notably the lab led by David Reich at Harvard, have developed methods for extracting aDNA and using computers and statistics to reconstruct a full genetic sequence. aDNA findings by Reich, Johannes Krause at the Max Planck Institute, and others, are challenging long-held assumptions about human origins hundreds of thousands of years ago and, more recently, human migrations such as those of Indo-Europeans and Pacific Islanders.

The genetic similarity of modern humans suggests that the population from which all Homo sapiens descended originated in Africa more than 250,000 years ago. When these humans began to move out of Africa as long as 180,000 years ago, they spread eastward into Southwest Asia and then throughout the rest of Afro-Eurasia. One group migrated to Australia about 50,000 years ago. Another group moved into the area of Europe about 40,000 years ago. When the scientific journal Nature in 1987 published genetic-based findings about humans’ spread across the planet, it inspired a groundswell of public interest—and a contentious scientific debate that continues today, as the more recent work by David Reich demonstrates.

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- How has the study of prehistory changed since the mid-twentieth century?

- Why are different dating methods appropriate for different kinds of artifacts?

- How does the study of climate and environment relate to the origins of humans?

Explore Further

- Barham, Lawrence, and Peter Mitchell, The First Africans: African Archaeology from the Earliest Toolmakers to Most Recent Foragers (2008).

- Barker, Graeme, Agricultural Revolution in Prehistory: Why Did Foragers Become Farmers? (2006).

- Christian, David, Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History (2004).

- Lewis-Kraus, Gideon, “Is Ancient DNA Research Revealing New Truths—Or Falling into Old Traps,” New York Times Magazine (2019).

- Reich, David, Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past (2018).

LUCY Australopithecines existed not only in southern Africa but in the north as well. In 1974, an archaeological team working at a site in present-day Ethiopia unearthed a relatively intact skeleton of a young adult female australopithecine near the Awash River. Anthropologist Donald Johanson, in Lucy’s Legacy, describes the lucky circumstances that saw him and a graduate student surveying the plateau on which Lucy’s ulna (elbow bone) first caught his eye. Studying the find that evening back in camp, Johanson’s team gave the skeleton a nickname, Lucy, based on the then-popular Beatles song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.”

Lucy—whose other, perhaps less catchy, early nickname was Dinkinesh, meaning “you are marvelous” in Ethiopian—was indeed extraordinary. She stood a little over 3 feet tall, she walked upright, her skull contained a brain within the ape size range, and her jaw and teeth were human-like. Her arms were long, hanging halfway from her hips to her knees, and her legs were short—suggesting that she was a skilled tree climber, might not have been two-footed at all times, and sometimes resorted to arms for locomotion, in the fashion of a modern baboon. Above all, Lucy’s skeleton was very, very old—half a million years older than any other complete hominin skeleton found up to that time. Johanson experienced a nervous moment when he first shared his analysis of Lucy with an assembly of his skeptical peers at a symposium in 1978. But after much arguing and convincing, Johanson earned his colleagues’ acceptance that he had found a new member of the human story. Eventually, Lucy left the scholarly world with no doubt that human precursors were walking around as early as 3 million years ago. (See Table 1.1.)

|

TABLE 1.1 | Human Evolution |

|

|

SPECIES |

TIME* |

|

Sahelanthropus tchadensis (including Toumai skull) |

7 MILLION YEARS AGO (MYA) |

|

Orrorin tugenensis |

6 MYA |

|

Ardipithecus ramidus (including Ardi) |

4.4 MYA |

|

Australopithecus anamensis |

4.2 MYA |

|

Australopithecus afarensis (including Lucy) |

3.9 MYA |

|

Australopithecus africanus (including Taung child) |

3.0 MYA |

|

Homo habilis (including Dear Boy) |

2.5 MYA |

|

Homo erectus and Homo ergaster (including Java and Peking Man) |

1.8 MYA |

|

Homo heidelbergensis (common ancestor of Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens) |

600,000 YEARS AGO |

|

Homo neanderthalensis |

400,000 YEARS AGO |

|

Homo sapiens |

300,000 YEARS AGO |

|

Homo naledi |

c. 280,000 YEARS AGO |

|

Homo sapiens sapiens (modern humans) |

35,000 YEARS AGO |

|

Source: Smithsonian Institute Human Origins Program. |

|

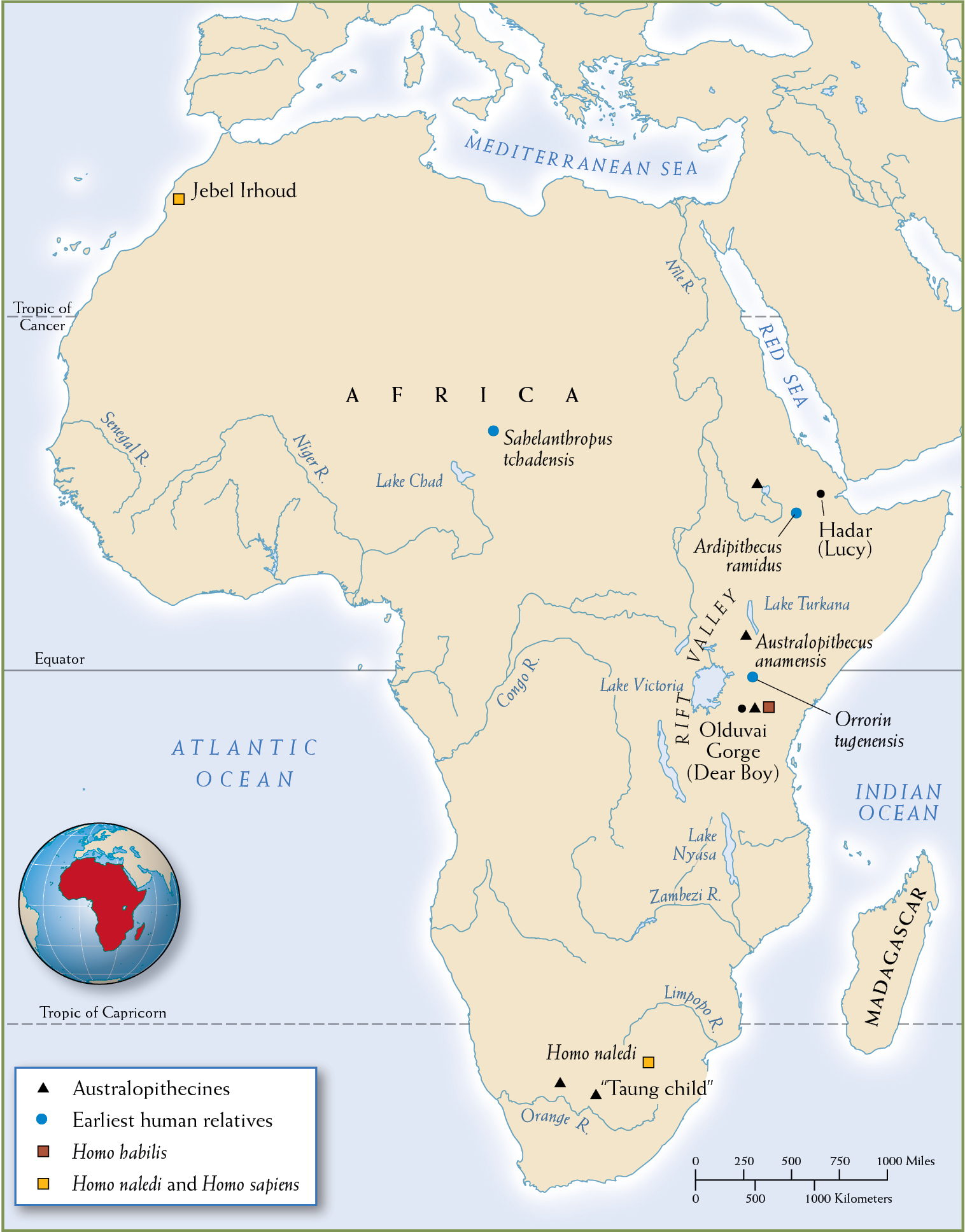

ADAPTATION To survive, hominins had to adapt and evolve to keep pace with physical environments that underwent rapid and destabilizing change—for if they did not, they would die out. Many of the early hominin groups did just that. The places where researchers found early hominin remains in southern and eastern Africa were characterized by drastic changes in the earth’s climate, with regions going from being heavily forested and well watered to being arid and desertlike and then back again. Survival required constant adaptation (the ability to alter behavior and to innovate) and finding new ways of doing things. Some hominin groups were better at it than others. (See Map 1.1.)

In adapting, early hominins began to distinguish themselves from other mammals that were physically similar to themselves. It was not their hunting prowess that made the hominins stand out, because plenty of other species chased their prey with skill and dexterity. The major trait at this stage that gave early hominins a real advantage for survival was bipedalism: they became “two-footed” creatures that stood upright. At some point, the first hominins were able to remain upright and move about, leaving their arms and hands free for various useful tasks, such as carrying food over long distances. Once they ventured into open savannas (grassy plains with a few scattered trees), about 1.7 million years ago, hominins had a tremendous advantage. They were the only primates (an order of mammals consisting of humans, apes, and monkeys) to move consistently on two legs. Because they could move continuously and over great distances, they were able to migrate out of hostile environments and into more hospitable locations as needed.

MAP 1.1 | Early Hominins

The earliest hominin species evolved in Africa millions of years ago.

- Judging from this map, in which parts of Africa has evidence for hominin species been excavated?

- Use Table 1.1 to assign dates to these hominin finds. What, if any, hypotheses might you suggest to correlate the geographic spread of the finds with the evolution of hominin species over time?

- According to this chapter, how did the changing environment of eastern and southern Africa shape the evolution of these modern human ancestors?

Explaining why and how hominins began to walk on two legs is critical to understanding our human origins and how humans became differentiated from other animal groups. Along with the other primates, the first hominins enjoyed the advantages of being long-limbed, tree-loving animals with good vision and dexterous hands. Why did these primates, in contrast to their closest relatives (gorillas and chimpanzees), leave the shelter of trees and venture out into the open grasslands, where they were vulnerable to attack? The answer is not self-evident. Explaining how and why some apes took these first steps also sheds light on why humanity’s origins lie in Africa. Fifteen million years ago there were apes all over the world, so why did a small number of them evolve new traits in Africa?

ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGES Approximately 40 million years ago, the world endured its fourth great ice age, during which the earth’s temperatures plunged and its continental ice sheets, polar ice sheets, and mountain glaciers expanded. We know this because during the last several decades paleoclimatologists have used measurements of ice cores and oxygen isotopes in the ocean to chart the often-radical changes in the world’s climate. The fourth great ice age lasted until 12,000 years ago. Like all ice ages, it had warming and cooling phases that lasted between 40,000 and 100,000 years each. Between 10 and 12 million years ago, the climate in Africa went through one such cooling and drying phase. To the east of Africa’s Rift Valley, stretching from South Africa north to the Ethiopian highlands, the cooling and drying forced the forests to contract and the savannas to spread. It was in this region that some apes came down from the trees, stood up, and learned to walk, to run, and to live in savanna lands—thus becoming the precursors to humans and distinctive as a new species. Using two feet for locomotion augmented the means for obtaining food and avoiding predators and improved the chances of these creatures to survive in constantly changing environments.

In addition to being bipedal, hominins had another trait that helped them survive: opposable thumbs. This trait, shared with other primates, gave hominins great physical dexterity, enhancing their ability to explore and to alter materials found in nature—especially to create and use tools. They also used increased powers of observation and memory, what we call cognitive skills (such as problem solving and—much later—language), to gather wild berries and grains and to scavenge the meat and marrow of animals that had died of natural causes or as the prey of predators. All primates are good at these activities, but hominins excelled at them. Cognition was destined to become the basis for further developments and was another characteristic that separated hominins from their closest species.

The early hominins were highly social. They lived in bands of about twenty-five individuals, surviving by hunting small game and gathering wild plants. Not yet a match for large predators, they had to find safe hiding places. They also sought ecological niches where a diverse supply of wild grains and fruits and abundant wildlife ensured a secure, comfortable existence. In such locations, small hunting bands of twenty-five could swell through alliances with others to as many as 500 individuals. Hominins, like other primates, communicated through gestures, but they also may have developed an early form of spoken language that led (among other things) to the establishment of rules of conduct, customs, and identities.

These early hominins lived in this manner for more than 4 million years, changing their way of life very little except for moving around the African landmass in their never-ending search for more favorable environments. Even so, their survival is surprising. There were not many of them, and they struggled in hostile environments surrounded by a diversity of large mammals, including predators such as lions.

As the environment changed over the millennia, these early hominins gradually altered in appearance. Over this 4-million-year period, their brains more than doubled in size; their foreheads became more elongated; their jaws became less massive; and they began to look much more like modern humans. Adaptation to environmental changes also created new skills and aptitudes, which expanded the ability to store and analyze information. With larger brains, hominins could form a mental map of their world—they could learn, remember what they learned, and convey these lessons to their neighbors and offspring. In this fashion, larger groups of hominins created communities with a shared understanding of their environment.

DIVERSITY Recent discoveries in Kenya, Chad, and Ethiopia suggest that hominins were both older and more diverse than early australopithecine finds (both afarensis and africanus) had suggested. In southern Kenya in 2000, researchers excavated bone remains, at least 6 million years old, of a chimpanzee-sized hominid (named Orrorin tugenensis) that walked upright on two feet. In Chad in 2001, another team unearthed the 7-million-year-old “Toumai skull,” with a mix of attributes (small cranial capacity like a chimp’s but more human-like teeth and spinal column placement at the base of the skull) that perplexed researchers but led them to place this new find, technically named Sahelanthropus tchadensis, in the story of human evolution. These finds indicate that bipedalism must be millions of years older than scientists thought based on discoveries like Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis) and “Taung child” (Australopithecus africanus). Moreover, Orrorin and Sahelanthropus teeth indicate that they were closer to modern humans than to australopithecines. In their arms and hands, though, which show characteristics needed for tree climbing, the Orrorin hominins seemed more ape-like than the australopithecines. So Orrorin hominins were still somewhat tied to an environment in the trees. Only the chimp-sized skull fragments of Sahelanthropus have been found, so no conclusions about their bodies, other than that they walked upright, can be drawn.

The fact that different kinds of early hominins were living in isolated societies and evolving separately, though in close proximity to one another, in eastern Africa between 4 and 3 million years ago until as recently as 300,000 years ago indicates much greater diversity among their populations than scholars previously imagined. The environment in eastern Africa generated a fair number of different hominin populations, a few of which would provide our genetic base, but most of which would not survive in the long run.

Homo habilis and the Debate over Who the First Humans Were

One million years after Lucy, the first beings whom we assign to the genus Homo, or “true human,” appeared. They, too, were bipedal, possessing a smooth walk based on upright posture. And they had an even more important advantage over other hominins, brains that were growing larger. Big brains are the site of innovation, learning and storing lessons so that humans can pass those lessons on to offspring, especially in the making of tools and the efficient use of resources (and, we suspect, in defending themselves). British paleontologists Mary and Louis Leakey, who made astonishing fossil discoveries in the 1950s at Olduvai Gorge (part of the Great Rift Valley) in present-day northeastern Tanzania, identified these important traits. The Leakeys’ finds are the most significant discoveries of early humans in Africa—in particular, an intact skull that was 1.8 million years old. The Leakeys nicknamed the creature whose skull they had unearthed Dear Boy because the discovery meant so much to them and their research into hominins.

Other objects discovered with Dear Boy demonstrated that by this time early humans had begun to make tools for butchering animals and, possibly, for hunting and killing smaller animals. The tools were flaked stones with sharpened edges for cutting apart animal flesh and scooping out the marrow from bones. To mimic the slicing teeth of lions, leopards, and other carnivores, the Oldowans had devised these tools through careful chipping. Dear Boy and his companions had carried usable rocks to distant places, where they made their implements with special hammer stones—tools to make tools. Unlike other tool-using animals (for example, chimpanzees), early humans were now intentionally fashioning implements, not simply finding them when needed. Because the Leakeys believed that making and using tools represented a new stage in the evolution of human beings, they gave these creatures a new name: Homo habilis, or “skillful man.” By using the term Homo for them, the Leakeys implied that they were the first truly human creatures in the evolutionary scheme. According to the Leakeys, their toolmaking ability made them the forerunners, though very distant, of modern men and women.

Although the term Homo habilis continues to be employed for these creatures, in many ways, especially in their brain size, they were not distinctly different from their australopithecine predecessors. In fact, just which of the many creatures warrant being seen as the world’s first truly human beings turns on what traits are identified as most decisive in distinguishing bipedal apes from modern humans. If that trait is toolmaking, then Homo habilis is the first; if being entirely bipedal, then Homo erectus is the one; if having a truly large brain, then it might be Homo sapiens or their immediate predecessors.

Early Hominins on the Move: Homo erectus

Many different species of hominins flourished together in Africa between 2.5 and 1 million years ago. By 1 million years ago, however, many had died out. One surviving species, which emerged about 1.8 million years ago and was destined to remain in existence until 200,000 years ago, had a large brain capacity and walked truly upright; in fact, its gait was remarkably similar to that of modern humans. Its gait gave it a capacity to run great distances because it had an endurance that no other primate possessed. Hence, this species gained the name Homo erectus, or “standing human.” Homo erectus also enjoyed superior eye-hand coordination and used this skill to throw hand axes at herds of animals. In addition, it looked more human than earlier groups did, for it had lost much of its hair and had developed darker skin as protection from the sun’s rays. Even though this species was more able to cope with environmental changes than other hominins had been, its story was not a predictable triumph. Only with the hindsight of millions of years can we understand the decisive advantage of intelligence over brawn—larger brains over larger teeth. Indeed, there were many more failures than successes in the gradual changes that led Homo erectus to be one of the few hominin species that would survive until the arrival of Homo sapiens.

INFANT CARE AND FAMILY DYNAMICS One of the traits that contributed to the survival of Homo erectus was the development of extended periods of caring for their young. Although their enlarged brain gave these hominins advantages over the rest of the animal world, it also brought one significant problem: their head was too large to pass through the female’s pelvis at birth. Their pelvis was only big enough to deliver an infant with a cranial capacity that was about one-third an adult’s size. As a result, offspring required a long period of protection by adults while they matured and their brain size tripled.

This difference from other species also affected family dynamics. For example, the long maturation process gave adult members of hunting and gathering bands time to train their children in those activities. In addition, maturation and brain growth required mothers to spend years breast-feeding and then preparing food for children after their weaning. To share the responsibilities of child-rearing, mothers relied on other women (their own mothers, sisters, and friends) and girls (often their own daughters) to help in the nurturing and protecting, a process known as allomothering (literally, “other mothering”).

USE OF FIRE Homo erectus began to make rudimentary attempts to control their environment by means of fire—another significant marker in the development of human culture. It is hard to tell from fossils when humans learned to use fire. The most reliable evidence comes from cave sites, less than 250,000 years old, where early humans apparently cooked some of their food. Less conservative estimates suggest that human mastery of fire occurred nearly 500,000 years ago. Fire provided heat, protection from wild animals, a gathering point for small communities, and, perhaps most important, a way to cook food. It was also symbolically powerful, for here was a source of energy that humans could extinguish and revive at will. Because they were able to boil, steam, and fry wild plants as well as otherwise-indigestible foods (especially raw muscle fiber), early humans could expand their diets. Because cooked foods yield more energy than raw foods and because the brain, while only 2 percent of human body weight, uses between 20 and 25 percent of all the energy that humans take in, cooking was decisive in the evolution of brain size and functioning.

EARLY MIGRATIONS The populating of the world by hominins proceeded in waves. Around 1.5 million years ago, Homo erectus individuals migrated first into the lands of Southwest Asia. From there, they traveled along the Indian Ocean shoreline, moving into South Asia and Southeast Asia and later northward into what is now China. Their migration was a response in part to the environmental changes that were transforming the world. The Northern Hemisphere experienced thirty major cold phases during this period, marked by glaciers (huge sheets of ice) spreading over vast expanses of the northern parts of Eurasia and the Americas. The glaciers formed as a result of intense cold that froze much of the world’s oceans, lowering them some 325 feet below present-day levels. So it was possible for the migrants to travel across land bridges into Southeast Asia and from East Asia to Japan, as well as from New Guinea to Australia. The last parts of the Afro-Eurasian landmass to be occupied were in Europe. The geological record indicates that ice mantles blanketed the areas of present-day Scotland, Ireland, Wales, Scandinavia, and the whole of northern Europe (including the areas of present-day Berlin, Warsaw, Moscow, and Kiev). Here, too, a lowered ocean level enabled human predecessors to cross by foot from areas in Europe into what is now England.

It is astonishing how far Homo erectus traveled. Discoveries of the bone remains of “Java Man” and “Peking Man” (named according to the places where archaeologists first unearthed their remains) confirmed early settlements of Homo erectus in Southeast and East Asia. The remains of Java Man, found in 1891 on the island of Java, turned out to be those of an early Homo erectus that had dispersed into Asia nearly 2 million years ago. Peking Man, found near Beijing in the 1920s, was a cave dweller, toolmaker, and hunter and gatherer who settled in northern China. Originally believing that Peking Man dated to around 400,000 years ago, archaeologists thought that warmer climate might have made the region more hospitable to migrating Homo erectus. But recent application of the aluminum-beryllium technique to analyze the fossils has suggested they date to 770,000 years ago, a time when China’s climate would have been much colder. Peking Man’s brain was larger than that of his Javan cousins, and there is evidence that he controlled fire and cooked meat in addition to hunting large animals. He made tools of vein quartz, quartz crystals, flint, and sandstone. A major innovation was the double-faced axe, a stone instrument whittled down to sharp edges on both sides to serve as a hand axe, a cleaver, a pick, and probably a weapon to hurl against foes or animals. Even so, these early predecessors lacked the intelligence, language skills, and ability to create culture that would distinguish the first modern humans from their hominin relatives.

Rather than seeing human evolution as a single, gradual development, scientists increasingly view our origins as shaped by a series of progressions and regressions as hominins adapted or failed to adapt and went extinct (died out). Several species existed simultaneously, but some were more suited to changing environmental conditions—and thus more likely to survive—than others. The early settlers of Afro-Eurasia from the Homo erectus group went extinct around 200,000 years ago. Yet we are not their immediate descendants. Although the existence of Homo erectus may have been necessary for the evolution into Homo sapiens, it was not, in itself, sufficient.

The story of hominin evolution continues to unfold and demonstrates that hominin diversity continued to thrive in Africa even as other hominins, like Homo erectus, migrated out of the continent. Far inside a cave near Johannesburg, South Africa, spelunkers recently made a discovery that led to the excavation of more than 1,550 fossil remains (now named Homo naledi, for the cave in which they were found). Researchers have been able to assemble a composite skeleton that revealed that the upper body parts resembled some of the much earlier pre-Homo finds, while the hands (both the palms and curved fingers), wrists, the long legs, and the feet are close to those of modern humans. The males were around 5 feet tall and weighed 100 pounds, while the females were shorter and lighter. Recent publications have suggested a surprisingly late date range of 335,000 to 236,000 years ago, and therefore much research remains to be done to determine how these fossils fit the story of human evolution.

Glossary

- evolution

- Process by which species of plants and animals change over time, as a result of the favoring, through reproduction, of certain traits that are useful in that species’ environment.

- australopithecines

- Hominin species, including anamensis, afarensis (Lucy), and africanus, that appeared in Africa beginning around 4 million years ago and, unlike other animals, sometimes walked on two legs. Their brain capacity was a little less than one-third of a modern human’s. Although not humans, they carried the genetic and biological material out of which modern humans would later emerge.

- Homo habilis

- Species, confined to Africa, that emerged about 2.5 million years ago and whose toolmaking ability truly made it the forerunner, though a very distant one, of modern humans. Homo habilis means “skillful human.”

- Homo erectus

- Species that emerged about 1.8 million years ago, had a large brain, walked truly upright, migrated out of Africa, and likely mastered fire. Homo erectus means “standing human.”

Notes

- Dates are approximate (midpoint on a range), based on multiple finds. Some species are represented with hundreds of examples (more than 300 examples of Australopithecus afarensis, of which “Lucy” is the most famous, date across a span of almost 1 million years), while the evidence for other species is more limited (Sahelanthropus tchadensis is represented by a single skull). Return to reference *