![]() Monumental Architecture

Monumental Architecture

BETWEEN THE TIGRIS AND EUPHRATES RIVERS: MESOPOTAMIA

The world’s first complex society arose in Mesopotamia. Mesopotamia, from the Greek meaning “land between two rivers,” was a large landmass that included all of modern Iraq, eastern Syria, and southeastern Turkey. From their headwaters in the mountains to the north and east to their destination in the Persian Gulf, the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers are wild and unpredictable.

Providing water for irrigation, they also marked routes for transportation and communication by pack animal. Unpredictable waters can wipe out years of hard work, but when managed properly they can transform the landscape into verdant and productive fields. Here men and women, using abundant supplies of water and rich agricultural lands, established large cities and dramatically new cultural, political, and social institutions. By 3500 BCE, in a world where people had been living close to the land in small clans and settlements, a radical breakthrough occurred in this one place. Here the world’s first complex society arose. Here the city and the rivers changed how people lived.

Tapping the Waters

The first rudimentary advances in irrigation occurred in the foothills of the Zagros Mountains along the banks of the smaller rivers that feed the Tigris. Converting the floodplain—where the river overflows and deposits fertile soil—into a breadbasket required mastering the unpredictable waters. Both the Euphrates and the Tigris, unless controlled by waterworks, were unfavorable to cultivators because the annual floods occurred at the height of the growing season, when crops were most vulnerable. Low water levels occurred when crops required abundant irrigation. To prevent the river from overflowing during its flood stage, farmers built levees along the banks and dug ditches and canals to drain away the floodwaters. Engineers devised an irrigation system whereby the Euphrates, which has a higher riverbed than the Tigris, essentially served as the supply and the Tigris as the drain. Storing and channeling water year after year required constant maintenance and innovation by a corps of engineers.

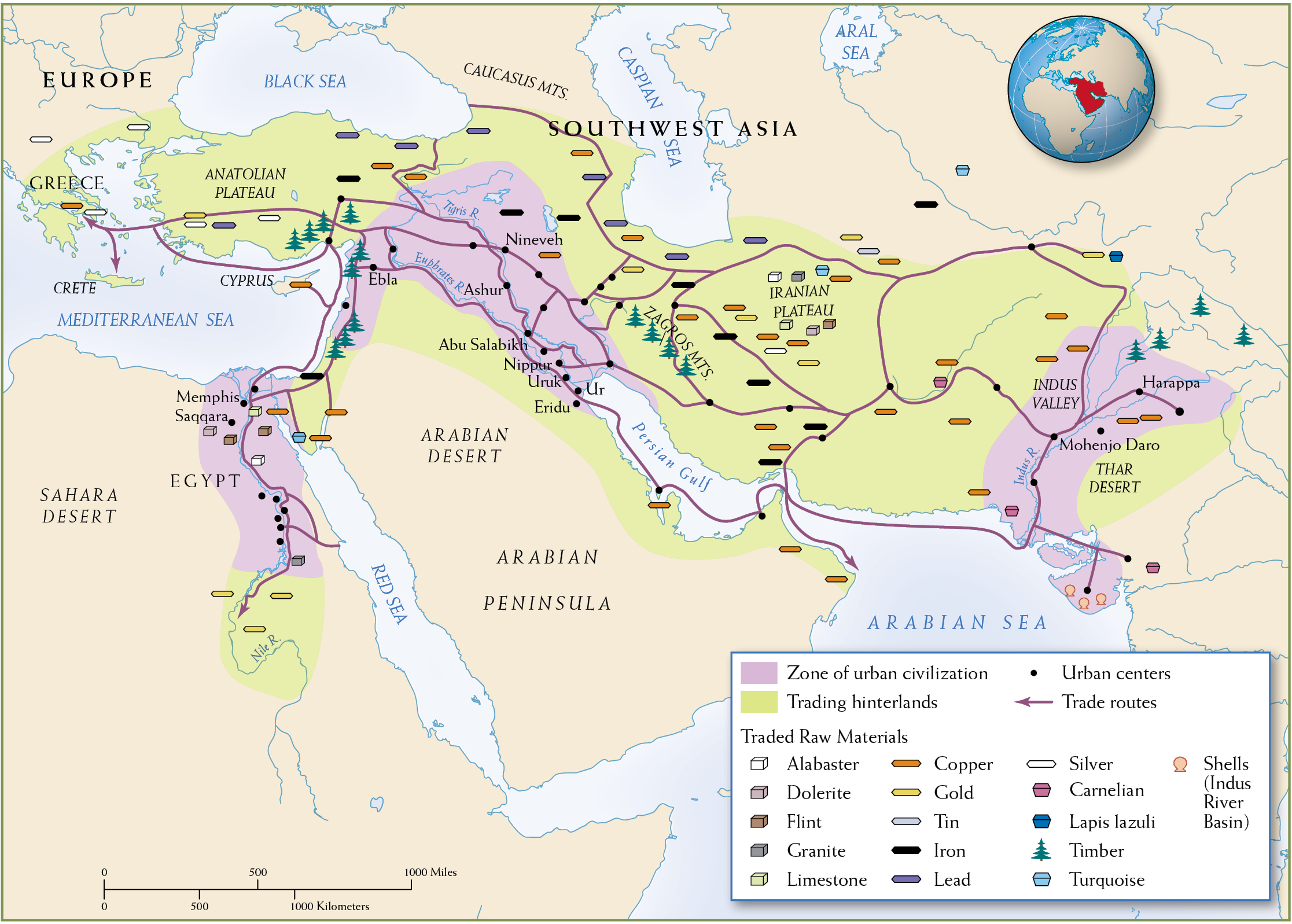

MAP 2.2 | Trade and Exchange in Southwest Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean, Third Millennium BCE

Extensive commercial networks linked the urban cores of Southwest Asia.

- Of the traded raw materials shown on the map, which ones were used for building materials and which ones for luxury items?

- Which regions had timber and which regions did not? How would the needs of river-basin societies have influenced trade with the regions that had timber?

- Using the map, describe the extent and likely routes of trade necessary for the creation of the treasures of Ur in Mesopotamia (with items fashioned from gold, lapis lazuli, and carnelian) and the wealth buried with kings of Egypt in their pyramids (silver, gold, lapis lazuli, and carnelian).

The Mesopotamian technological breakthrough was in irrigation, not in agrarian methods. Because the soils were fine, rich, and constantly replenished by the floodwaters’ silt, soil tillage was light work. Farmers sowed a combination of wheat, millet, sesame, and barley (the basis for beer, a staple of their diet). Unforeseen, however, was the danger of planting every year, for by the third millennium the fertile soils had been destroyed by the constant accumulation of salts deposited through constant use.

Crossroads of Southwest Asia

Though its soil was rich and water was abundant, southern Mesopotamia had few other natural resources apart from mud, marsh reeds, spindly trees, and low-quality limestone that served as basic building materials. To obtain high-quality, dense wood, stone, metal, and other materials for constructing and embellishing their cities (notably their temples and palaces), Mesopotamians interacted with the inhabitants of surrounding regions. Thus, long-distance trade was vitally important to the cities of southern Mesopotamia. In return for textiles, specialty foods, oils, and other commodities, they imported cedar wood from Lebanon, copper and stones from Oman, more copper from Turkey and Iran, and the precious blue gemstone called lapis lazuli, as well as the ever-useful tin, from faraway Afghanistan. Providing colorful stones, gold, and silver to adorn the temples and to embellish the elites, as well as useful copper and tin that when combined make bronze, this trade was fundamental to the development of the social and political hierarchy in Mesopotamia. Maintaining trading contacts was easy, given Mesopotamia’s open boundaries on all sides. By 3000 BCE, there was extensive interaction between southern Mesopotamia and the highlands of Anatolia, the forests of the Levant bordering the eastern Mediterranean, and the rich mountains and vast plateau of Iran. (See again Map 2.2.)

Mesopotamia became a magnet for waves of newcomers from the deserts and the mountains and thus a crossroads for the peoples of Southwest Asia, the meeting grounds for distinct cultural and linguistic groups. Among the dominant groups were Sumerians, who concentrated in the south; Hurrians, who lived in the north; and Akkadians, who populated western and central Mesopotamia.

The World’s First Cities

During the first half of the fourth millennium BCE, a demographic transformation occurred in the southern part of the Tigris-Euphrates River basin. This was an area stretching from present-day Baghdad to the Persian Gulf (usually referred to by scholars as Babylonia, even though a city in the location of Babylon did not emerge until the latter part of the third millennium BCE). The population here expanded as a result of the region’s agricultural bounty, political advances, and the swelling ranks of Mesopotamians, who migrated from country villages to centers that eventually became cities. (A city is a large, well-defined urban area with a dense population.) Although this area was relatively small, it possessed significant geographical diversity that served it well. To the west was an uninhabitable desert plateau. The farming lands and cities existed in the irrigated zones in the south, while beyond the river valley the mountainous regions to the north and east permitted the herding of livestock.

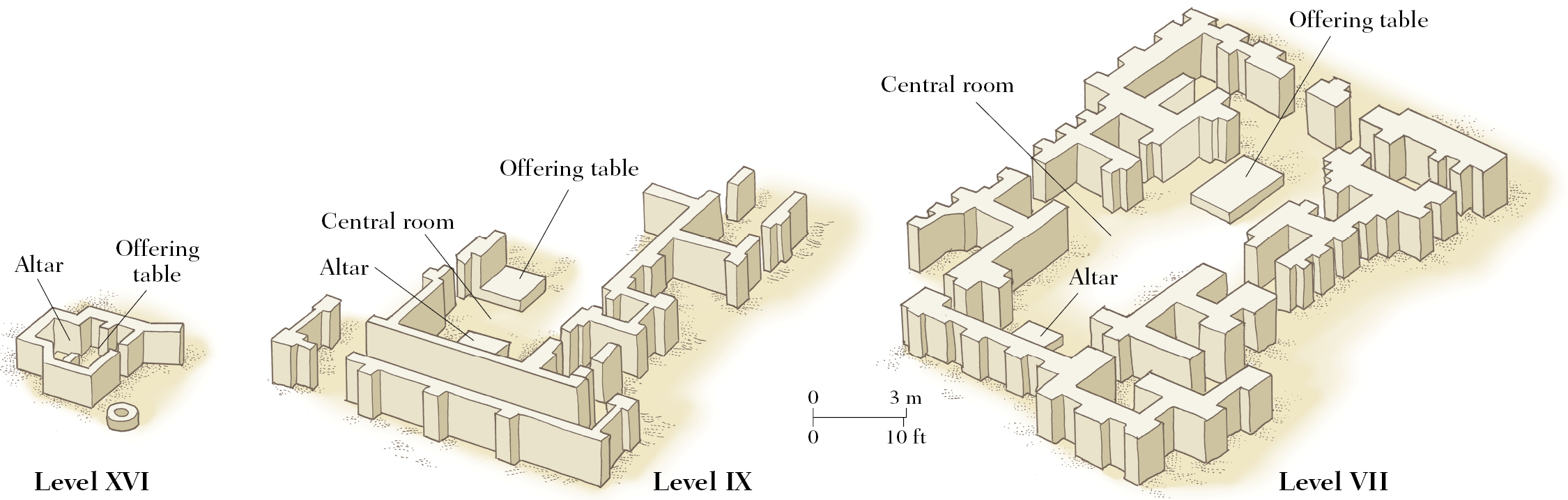

The earliest cities—Uruk, Eridu, and Nippur—developed over about 1,000 years, dominating the southern part of the floodplain by 3500 BCE. Here archaeologists have found buildings of mud brick marking successive layers of urban development. Consider Eridu, a village dating back to 6000 BCE. Eridu was a sacred site where temples piled up on top of one another for over 4,000 years. The final temple rose from a platform like a mountain, visible for miles in all directions, and was the home of the patron deity. The god’s household was presided over by a coterie of priests, the most important of whom had substantial political powers.

As the temple grew skyward, the village expanded outward and became a city. Gods oversaw the sprawl. From their homes in temples located at the center of cities, they broadcast their powers through the priestly class. In return, urbanites provided finery, clothes, and enhanced lodgings for the gods and their priestly envoys. In Sumerian cosmology, humans were created solely to serve the gods, so the urban landscape reflected this fact: with a temple at the core, with goods and services flowing to the center, and with divine protection and justice flowing outward.

Some thirty-five of these politically equal city-states with divine sanctuaries dotted the southern plain of Mesopotamia. (A city-state is a political organization based on the authority of a single, large city that controls the surrounding countryside.) Local communities in these urban hubs expressed homage to individual city gods and took pride in the temple, the god’s home.

Because early Mesopotamian cities served as meeting places for peoples and their deities, they gained status as religious, political, and economic centers. Whether enormous (like Uruk and Nippur) or modest (like Ur and Abu Salabikh), all cities were spiritual, economic, and cultural homes for Mesopotamian subjects and places where considerable political power was exercised.

Simply making a city was not enough: it had to be made great. Urban design reflected the city’s role as a wondrous place to pay homage to the gods and their human intermediary, the ruler figure. These early cities contained enormous spaces within their walls, with large houses separated by date palm plantations. The city limits also encompassed extensive sheepfolds, which became a frequent metaphor for the city in Sumerian literature. As populations grew, the Mesopotamian cities became denser and the houses smaller. Some urbanites established new suburbs, spilling out beyond old walls and creating neighborhoods in what used to be the countryside.

The typical layout of Mesopotamian cities reflected a common pattern: a central canal surrounded by neighborhoods of specialized occupational groups. The temple marked the city center, originally the supreme source of political authority, while the palace and other official buildings graced the periphery. In separate quarters for craft production, families passed down their trades across generations. In this sense, the landscape of the city mirrored the growing social hierarchies (distinctions between the privileged and the less privileged).

Gods and Temples

The worldview of the Sumerians and, later, the Akkadians included a belief in a group of gods that shaped their political institutions and controlled everything—including the weather, fertility, harvests, and the underworld. As depicted in the Epic of Gilgamesh (a second-millennium BCE composition based on oral tales about Gilgamesh, a historical but mythologized king of Uruk), the gods could give but could also take away—with searing droughts, unmerciful floods, and violent death. Gods, along with the natural forces they controlled, had to be revered and feared. Faithful subjects imagined their gods as immortal beings whose habits were capricious, contentious, and gloriously work-free.

Each major god of the Sumerian pantheon (an officially recognized group of gods and goddesses) dwelled in a lavish temple in a particular city that he or she had created; for instance, Enlil, god of air and storms, dwelled in Nippur; Enki (also called Ea), god of water, in Eridu; Nanna, god of the moon, in Ur; and Inanna (also called Ishtar), goddess of love, fertility, and war, in Uruk. These temples, and the patron deity housed within, gave rise to each city’s character, institutions, and relationships with its urban neighbors. Inside these temples, benches lined the walls, with statues of humans standing in perpetual worship of the deity’s images. By the end of the third millennium BCE, the temple’s platform base had changed to a stepped platform called a ziggurat, with the main temple on top. Surrounding the ziggurat were buildings that housed priests, officials, laborers, and servants.

While the temple was the god’s earthly residence, it was also the god’s estate. As such, temples functioned like large households, engaging in all sorts of productive and commercial activities. Their dependents cultivated cereals, fruits, and vegetables by using extensive irrigation. The temples owned vast flocks of sheep, goats, cows, and donkeys. Those located close to the river employed workers to collect reeds, to fish, and to hunt. Enormous labor forces were involved in maintaining this high level of production. Other temples operated huge workshops for manufacturing textiles and leather goods, employing craftworkers, metalworkers, masons, and stoneworkers. Yet temples also performed redistributive functions, returning some of their bounty to the city’s residents, thereby enhancing the power of each patron god and his or her priests.

Palaces, Burials, and Royal Power

Like the temples in which the gods dwelled, royal palaces reflected the power of the ruling elite. The palace, as both an institution and a set of buildings, appeared around 2500 BCE—about two millennia later than the Mesopotamian temple. Palaces emerged as cities expanded and came into conflict with other cities. Disputes led to the emergence of another dominant political figure—the warrior chief, who was at first chosen because of military skills. Over time, however, these powers passed within families, leading to royal dynasties. A palace (or egal, “big house”) was constructed on the outskirts of the city, in contrast to the founding temple, which stood at the center of the city. Like temples, palaces constituted significant landmarks of city life, upholding order and a sense of shared membership in city affairs. Over time, the palace became a source of power rivaling that of the temple, even though palaces were off-limits to most citizens unless connected to the royal court.

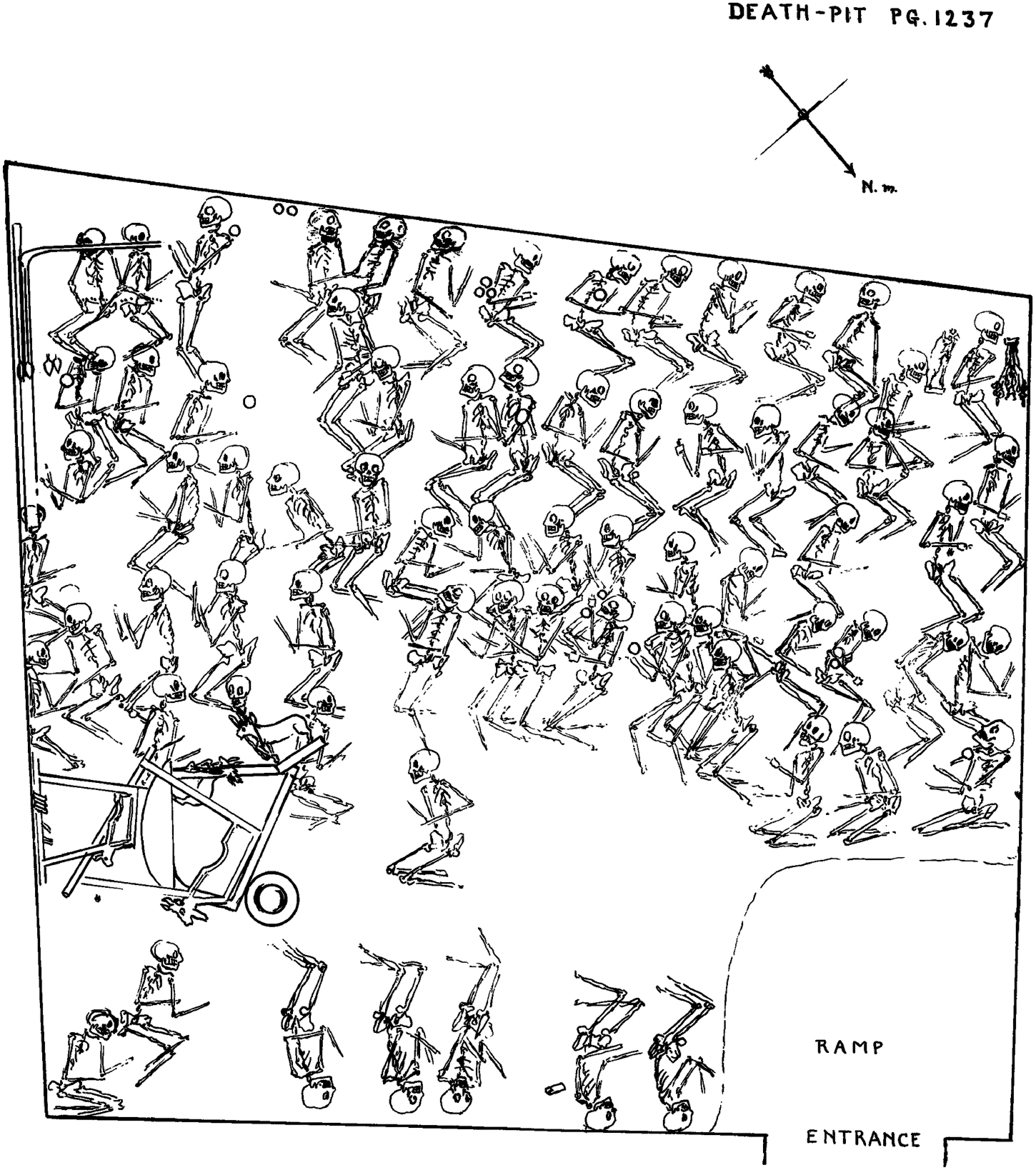

The Royal Cemetery at Ur shows how Mesopotamian rulers used elaborate burial arrangements to reinforce their religious and socioeconomic hierarchies. Housed in a mud-brick structure, the royal burials held not only the primary remains but also the bodies of people who had been sacrificed—in so-called Death Pit 1237, sixty-seven women and six men accompanied the elite woman whose elaborate burial it contains. Artifacts in the burials include huge vats for cooked food, bones of animals, drinking vessels, and musical instruments, all of which enable scholars to reconstruct the lifestyle of those who joined their masters in the graves. Honoring the royal dead by including their followers and possessions in their tombs reinforced the social hierarchies—including the vertical ties between humans and gods—that were the cornerstone of these early city-states.

First Writing and Early Texts

Mesopotamia was the birthplace of the world’s first writing system, inscribed to promote the power of the temples and kings in the expanding city-states. Small-scale hunting and gathering societies and village-farming communities had developed rituals of oral celebrations based on collective memories transmitted by families across generations. But as societies grew larger and more complex and their members more anonymous, oral traditions provided inadequate “glue” to hold the centers together.

Those who wielded new writing tools were scribes; from the very beginning, they were at the top of the social ladder, under the major power brokers—the king (lugal in Sumerian, literally meaning “big man”) and the priests. As the writing of texts became more important to the social fabric of cities and facilitated information sharing across wider spans of distance and time, scribes consolidated their grip on the upper rungs of the social ladder.

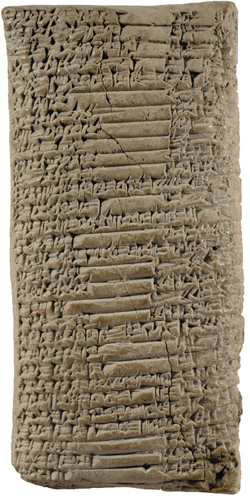

Mesopotamians became the world’s first record keepers and readers. The precursors to writing appeared in Mesopotamian societies when farming peoples and officials, who had been using clay tokens and images carved on stones to seal off storage areas, began to use them to convey messages. These images, when combined with numbers drawn on clay tablets, could record the distribution of goods and services.

In a flash of human genius, someone, probably in Uruk, understood that the marks (most were pictures of objects) could also represent words or sounds. Before long, scribes connected visual symbols with sounds, and sounds with meanings, and they discovered they could record messages by using symbols or signs to denote concepts. Such signs later came to represent syllables, the building blocks of words. (See Analyzing Global Developments: The Development of Writing.)

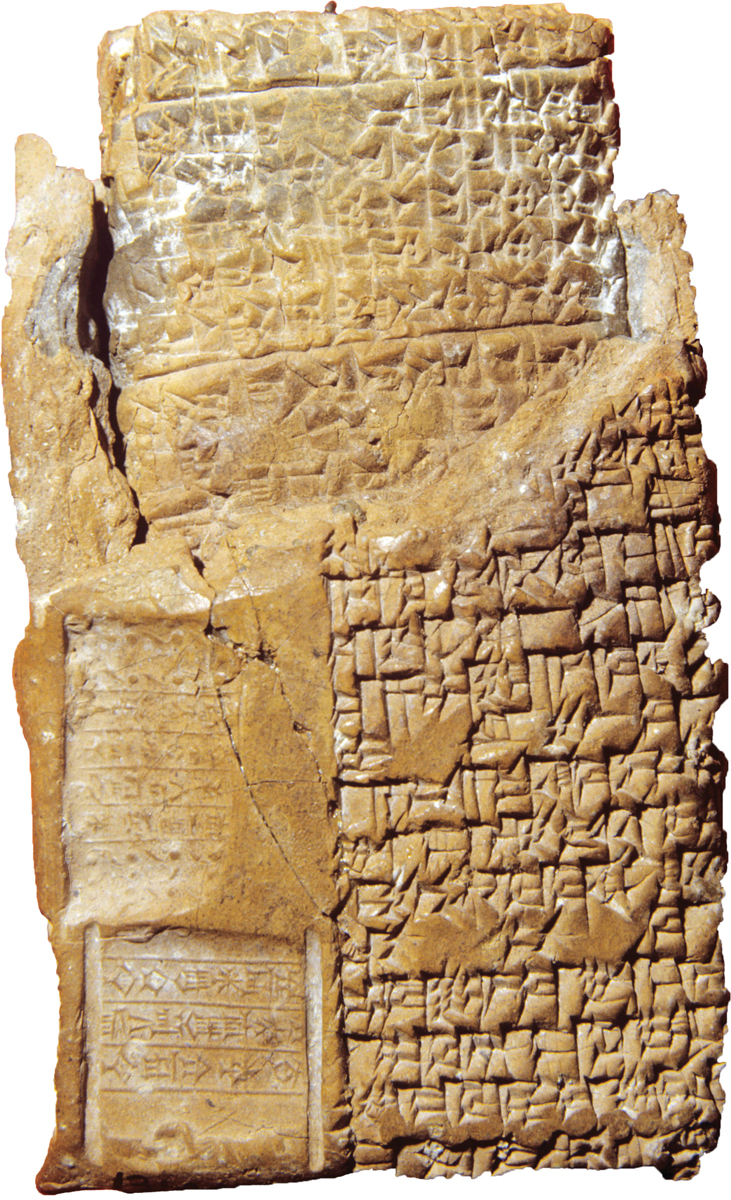

By impressing signs into wet clay with the cut end of a reed, scribes pioneered a form of wedge-shaped writing that we call cuneiform; it filled tablets with information that was intelligible to anyone who could decipher the signs, even in faraway locations or in future generations. At first, this Sumerian innovation was used exclusively to monitor and control economic transactions within the city-state: the distribution of sheep, goats, grain, rations, and textiles—and enslaved people—to supervisors or to the temple. Only hundreds of years later was the writing system used to transmit ideas through literature, historical records, and sacred texts. The result was a profound change in human experience, because representing symbols of spoken language facilitated an extension of communication and memory.

Much of what we know about Mesopotamia rests on scholars’ ability to decipher cuneiform script. By around 2400 BCE, texts began to describe the political makeup of southern Mesopotamia, giving details of its history and economy. Northern cities borrowed cuneiform to record economic transactions and political events, but in their own Semitic tongue. In fact, cuneiform’s adaptability to different languages was a main reason its use spread widely.

City life and literacy gave rise also to written narratives, the stories of a “people” and their origins. “The Temple Hymns,” written around 2100 BCE, describe thirty-five divine sanctuaries. The Sumerian King List, known from texts written around 2000 BCE, recounts the reigns of kings by city and dynasty and narrates the long reigns of legendary kings before the so-called Great Flood. A crucial event in Sumerian identity, the Great Flood, a pastoral-focused version of which is also found in biblical narrative, explained Uruk’s demise as the gods’ doing. Flooding was the most powerful natural force in the lives of those who lived by rivers, and it helped shape the foundations of Mesopotamian societies.

Cities Begin to Unify into “States”

Although no single city-state dominated the history of fourth- and third-millennium BCE Mesopotamia, a few stand out. The most powerful and influential were the Sumerian city-states of the Early Dynastic Age (2850–2334 BCE) and their successor, the Akkadians (2334–2193 BCE). While the city-states of southern Mesopotamia flourished and competed, giving rise to the land of Sumer, the rich agricultural zones to the north inhabited by the Hurrians also became urbanized. (See Map 2.3.) Beginning around 2600 BCE, northern cities were comparable in size to those in the south.

MAP 2.3 | The Spread of Cities in Mesopotamia and the Akkadian State, 2600–2200 BCE

Urbanization began in the southern river basin of Mesopotamia and spread northward. Eventually, the region achieved unification under Akkadian power.

- According to this map, what natural features influenced the location of Mesopotamian cities?

- Where were cities located before 2600 BCE, as opposed to afterward? What does the area under Akkadian power suggest that the Akkadian territorial state was able to do?

- How did the expansion northward reflect the continued influence of geographic and environmental factors on urbanization?

As Mesopotamia swelled with cities, it became unstable. The Sumerian city-states with expanding populations soon found themselves competing for agrarian lands, scarce water, and lucrative trade routes. And as pastoralists far and wide learned of the region’s bounty, they journeyed in greater numbers to the cities, fueling urbanization and competition.

ANALYZING GLOBAL DEVELOPMENTS

The Development of Writing

Agricultural surplus, and the urbanization and labor specialization that accompanied it, prompted the earliest development of writing and the profession of the scribes, whose job it was to write. Early forms of writing were employed for a variety of purposes, such as keeping financial and administrative records, recording the reigns of rulers, and documenting religious events and practices (calendars, rituals, and divinatory purposes). By the late third millennium BCE, some early societies (Mesopotamia and Egypt, in particular) used writing to produce literature, religious texts, and historical documents. Different types of writing developed in early societies, in part because each society developed writing for different purposes (see table):

- Ideographic/logographic/pictographic systems: symbols representing words (complex and cumbersome)

- Logophonetic and logosyllabic systems: symbols representing words, with a subset also representing sounds, usually syllables (fewer symbols)

- Syllabic systems: symbols representing syllables assembled to create words

- Alphabetic systems: letter symbols representing individual speech sounds assembled to create words

Scholars know more about early cultures whose writing has since been deciphered. Undeciphered scripts, such as the Indus Valley script and Rongorongo, offer intrigue and promise to those who would attempt to decipher them.

|

Name/Type of Society |

Writing Form and Date of Emergence |

Type of Writing and Purpose |

Date and Means of Decipherment |

|

Mesopotamia (Sumer)/river-basin (Tigris-Euphrates) |

Cuneiform, 3200 BCE |

Transitions from about 1,000 pictographs to about 400 syllables (record keeping) |

Deciphered in nineteenth century via Behistun/Beisitun inscription |

|

Egypt (Old Kingdom)/river-basin (Nile) |

Hieroglyphs, 3100 BCE |

Mixture of thousands of logograms and phonograms (religious) |

Deciphered in early nineteenth century via trilingual Rosetta Stone |

|

Harappan/river-basin (Indus) |

Indus Valley script, 2500 BCE |

375–400 logographic signs (nomenclature and titulature) |

Undeciphered (but headway being made with computer-assisted analysis) |

|

Minoan/Mycenaean Greece/seafaring microsociety |

Phaistos Disk and Linear A (Minoan Crete); Linear B (Mycenaean, Crete and Greece); 1900 BCE–1300 BCE |

Phaistos Disk (45 pictographic symbols in a spiral); Linear A (90 logographic-syllabic symbols); Linear B (roughly 75 syllabic symbols with some logographs) (record keeping) |

Phaistos (undeciphered); Linear A (undeciphered); Linear B (deciphered in mid-twentieth century) |

|

Shang Dynasty/river-basin (Yellow River) |

Oracle bone script, 1400–1100 BCE |

Thousands of characters (divinatory purposes) |

Deciphered in early twentieth century |

|

Maya/Central American rain forest |

Mayan glyphs, 250 BCE |

Mixture of logograms (numeric glyphs), phonograms (around 85 phonetic glyphs), and hundreds of “emblem glyphs” (record of rulers and calendrical purposes) |

Decipherment begun in twentieth century |

|

Vikings/seafaring (Scandinavia) |

Futhark (runic alphabet), 200 CE |

24 alphabetic runes (ritual use or to identify owner or craftsperson) |

Deciphered in nineteenth century |

|

Inca/Andean highlands |

Quipu, 3000? BCE |

Knotted cords, essentially a tally system (record keeping) |

Deciphered |

|

Easter Island/seafaring microsociety |

Rongorongo, 1500 CE |

120 glyphs (calendrical or genealogical) |

Undeciphered |

Sources: Chris Scarre (ed.) , The Human Past: World Prehistory and the Development of Human Societies (Thames and Hudson, 2005); Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza,Genes, Peoples, and Languages, translated by Mark Selestad from the original 1996 French publication (North Point Press, 2000).

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- What is the relationship between writing and the development of the earliest river-basin societies? (See also Map 2.1.)

- To what extent does the type of society (river-basin, seafaring, and so on) seem to affect the development of writing in that region (date, type, purpose, and so on)?

- How has the decipherment, or lack thereof, of these scripts affected scholars’ understanding of the societies that produced them?

Cities also spawned rivalry and struggles for supremacy. In fact, the world’s first great conqueror emerged from one of these cities, and by the end of his long reign he had united (by force) the independent Mesopotamian cities south of modern-day Baghdad. The legendary Sargon the Great (r. 2334–2279 BCE), king of Akkad, brought the era of competitive independent city-states to an end. His most remarkable achievement was unification of the southern cities through an alliance. Although this unity lasted only three generations, it represented the first multiethnic unification of urban centers—the territorial state (see Chapter 3). Just under a century after Sargon’s death, foreign tribesmen from the Zagros Mountains conquered the capital city of Akkad, bringing an end to the Akkadian state. Its collapse in 2190 BCE fueled epic history writing that depicted the struggles between city-state dwellers and those on the margins, who lived a simpler way of life.

The fall of Sargon’s Akkadian state underscores a fundamental but often neglected reality of the ancient world: living side by side with the city-state dwellers were peoples who often did not enter the historical record except when they intruded on the lives of their more powerful, prosperous, and literate neighbors. The most obvious legacy of Sargon’s dynasty was its sponsorship of monumental architecture, artworks, and literary works. These cultural achievements stood for centuries, inspiring generations of builders, architects, artists, and scribes. And by encouraging contact with distant neighbors, many of whom adopted aspects of Mesopotamian culture, the Akkadian kings increased the geographical reach of Mesopotamian influence.

Glossary

- city

- Highly populated concentration of economic, religious, and political power. The first cities appeared in river basins, which could produce a surplus of agriculture. The abundance of food freed most city inhabitants from the need to produce their own food, which allowed them to work in specialized professions.

- city-state

- Political organization based on the authority of a single, large city that controls outlying territories.

- scribes

- Those who wield writing tools; from the very beginning they were at the top of the social ladder, under the major power brokers.

Social Hierarchy and Families

Social hierarchies were an important part of the fabric of Sumerian city-states. Ruling groups secured their privileged access to economic and political resources by erecting systems of bureaucracies, priesthoods, and laws. Priests and bureaucrats served their rulers well, championing rules and norms that legitimized the political leadership. Mesopotamia’s city-states at first had assemblies of elders and young men who made collective decisions for the community. At times, certain effective individuals took charge of emergencies, and over time these people acquired more durable political power. The social hierarchy set off the rulers from the ruled.

Occupations within the cities were highly specialized, and a Sumerian lexical list names some of the most important professions. The king and priest, at the top of the hierarchy in Sumer, do not appear on the list. First come bureaucrats (scribes and household accountants), supervisors, and craftworkers. The latter included cooks, jewelers, gardeners, potters, metalsmiths, and traders. There were also independent merchants who risked long-distance trading ventures, hoping for a generous return on their investment. The biggest group, which was at the bottom of the hierarchy, comprised workers who were not enslaved but who were dependent on their employers’ households. Movement among economic classes was not impossible but, as in many traditional societies, it was rare.

The family and the household provided the bedrock for Sumerian society, and its patriarchal organization, dominated by the senior male, reflected the balance between women and men, children and parents. The family consisted of the husband and wife bound by a contract: she would provide children, preferably male, while he provided support and protection. Monogamy was the norm unless there was no son, in which case a second wife or an enslaved woman would bear male children to serve as the married couple’s offspring. Adoption was another way to gain a male heir. Sons would inherit the family’s property in equal shares, while daughters would receive dowries necessary for successful marriage into other families. Some women joined the temple staff as priestesses and gained economic autonomy that included ownership of estates and productive enterprises, although their fathers and brothers remained responsible for their well-being. The family hierarchy mirrored and also strengthened the social order.