THE SHANG TERRITORIAL STATE IN EAST ASIA

China’s first major territorial state combined features of earlier Longshan culture with new technologies and religious practices. Climatic change affected East Asia much as it had central and Southwest Asia. Stories written on bamboo strips and later collected into what historians called the “Bamboo Annals” tell of a time at the end of the legendary Xia dynasty when the sun dimmed and frost and ice appeared in the summer, followed by heavy rainfall, flooding, and then a long drought. According to Chinese mythology, the first ruler of the Shang state defeated a Xia king and then offered to sacrifice himself so that the drought would end. This leader, King Tang, survived to found the territorial state called Shang around 1600 BCE in northeastern China. (See Map 3.4.)

Following this climate-related power shift of lore, the Shang state was built on four elements that the Longshan peoples had already introduced: a metal industry based on copper; pottery making; walled towns; and divination using animal bones. To these Longshan foundations, the Shang dynasty added hereditary rulers whose power derived from their relation to ancestors and gods; large-scale metallurgy (especially in bronze); chariots for status and massive infantry for warfare; tribute; various rituals; and a distinctive form of writing.

State Formation

As in South Asia, the Shang political system gradually became more centralized from 1600 to 1200 BCE. Much like the territorial kingdoms of Southwest Asia, the Shang state did not have clearly established borders. To be sure, it faced threats—but not in the form of rival territorial states encroaching on its peripheries. Thus, it had little need for a strongly defended permanent capital, though its heartland was called Zhong Shang, or “center Shang.” Its capital moved as its frontier expanded and contracted. This relative security is evident in the Shang kings’ personalized style of rule, as they made regular trips around the country to meet, hunt, and conduct military campaigns with those who owed allegiance to them. Yet, like the territorial kingdoms of Southwest Asia, the Shang state had a ruling lineage (a line of male sovereigns descended from a common ancestor) that was eventually set down in a written record.

The Shang built on the agricultural and river-basin village cultures of the Longshan peoples, who had set the stage for an increasingly centralized state, urban life, and a cohesive culture (see Chapter 2). As the population increased and the number of village conflicts grew, it became necessary to have larger and more central forms of control. The Shang political system emerged to play that governmental role.

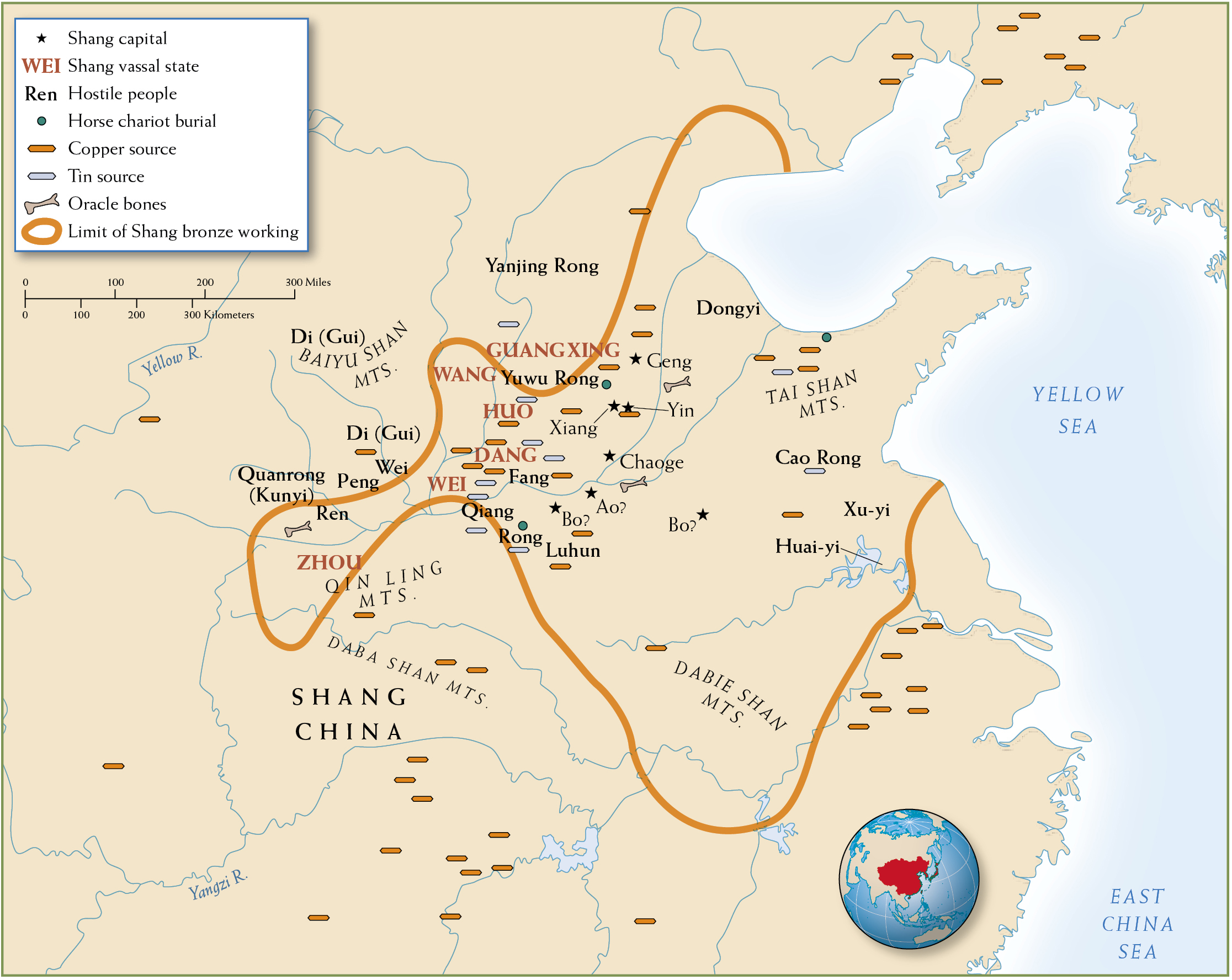

BRONZE METALLURGY Advanced Shang metalworking—the beginnings of which appeared in northwestern China at pre-Shang sites as early as 1800 BCE—was vital to the state. Metallurgical casting techniques were already in use at this time because copper and tin were available from the North China plain. (See Map 3.4.) Shang bronze work included weapons, fittings for chariots, and ritual vessels. Eventually, the new metallurgy technology gave the Shang unprecedented power over their neighbors.

Shang bronze-working techniques involved the use of hollow clay molds to hold the molten metal alloy, which, when removed after the liquid had cooled and solidified, produced firm bronze objects. The casting of modular components that artisans could assemble later promoted increased production and permitted the elite to make extravagant use of bronze vessels for burials. For example, archaeologists have unearthed a tomb at Anyang containing one enormous 1,925-pound bronze vessel; the Shang workshops had produced it in 1200 BCE. Another Anyang tomb from the same period contained 3,500 pounds of cast bronze.

MAP 3.4 | Shang Dynasty in East Asia

The Shang state was one of the most important and powerful of early Chinese dynasties.

- Based on your analysis of this map, what raw materials were the most important to the Shang state?

- How were the deposits of these raw materials distributed across Shang territory and beyond? How might that distribution have shaped the area marked on the map as the limit of Shang bronze working?

- Locate the various Shang capitals. Why do you think they were located where they were?

The bronze industry of this period shows a high level not only of material culture (the physical objects produced) but also of cultural development and aesthetic sensibility. Artisans skilled in the production of bronze produced ewers, tureens, boxes, and all manner of weapons; decorated jade, stone, and ivory objects; and wove silk on special looms. The bronzes were of the highest quality, decorated as they were with geometric patterns and animal designs featuring elephants, rams, tigers, horses, and more. Because Shang metalworking required extensive mining, it necessitated a large labor force, efficient casting, and a reproducible artistic style. Although the Shang state highly valued its artisans, it treated its copper miners as lowly tribute laborers.

By controlling access to tin and copper and to the production of bronze, the Shang rulers prevented their rivals from forging bronze weapons and thus increased their own power and legitimacy. With their superior weapons, Shang armies by 1300 BCE could easily destroy armies wielding wooden clubs and stone-tipped spears.

CHARIOTS FOR STATUS AND FOOTSOLDIERS FOR WAR Chariots entered the Central Plains of China together with nomads from the north around 1200 BCE, more than 500 years after the Hittites had used these vehicles to dominate much of Southwest Asia. Although the upper classes quickly assimilated them, chariots were not at first used extensively for military purposes and never achieved the military importance in China that they did elsewhere in Afro-Eurasia. Chariots may have been used less in the Shang era because the large Shang infantry forces were able to awe their enemies through sheer size and forged bronze weaponry. In Shang times, the chariots were used mostly for hunting and as a mark of high status, although Chinese chariots were much better built than those of their neighbors, having been improved by the addition of bronze fittings and harnesses. They were also larger than most of those in use in Egypt and Southwest Asia, accommodating three men standing in a box mounted on eighteen- or twenty-six-spoke wheels. As symbols of power and wealth, chariots were often buried with their owners.

Rather than employ chariots to defend their borders against neighboring states and pastoral nomads on the central Asian steppes, the Shang created armies composed mainly of foot soldiers, armed with axes, spears, arrowheads, shields, and helmets, all made of bronze. These forces prevailed at first, but eventually they lost ground, and the Shang territorial domain shrank until the regime was unable to resist invasion, in 1046 BCE, from its western neighbor and former tributary, the Zhou, who may have employed chariots in overcoming the much larger Shang armies.

As a patchwork of regimes, East Asia did not rise to the level of military-diplomatic jostling seen in Southwest Asia. Other large states developed alongside the Shang. These included relatively urban and wealthy peoples in the southeast and more rustic peoples bordering the Shang. The latter traded with the former, whom they knew as the Fang—their label for those who lived in non-Shang areas. Other kingdoms in the south and southwest also had independent bronze industries, with casting technologies comparable to those of the Shang. Nonetheless, Shang metalworking and the incorporation of chariots enabled the Shang state to expand territorially and to dominate its neighbors.

Agriculture and Tribute

The Shang rulers understood the importance of agriculture for winning and maintaining power, so they did much to promote its development. In fact, the activities of local governors and the masses revolved around agriculture. The rulers controlled their own farms, which supplied food to the ruling family, craftworkers, and the army. New technologies led to increased food production. Farmers drained low-lying fields and cleared forested areas to expand the cultivation of millet, wheat, barley, and possibly rice. Their implements included stone plows, spades, and sickles. In addition, farmers cultivated silkworms and raised pigs, dogs, sheep, and oxen. To best use the land and increase production, they tracked the growing season. And to record the seasons, the Shang developed a twelve-month, 360-day lunar calendar; it contained leap months to maintain the proper relationship between months and seasons. The calendar also relieved fears about events such as solar and lunar eclipses by making them predictable.

As in other Afro-Eurasian states, the ruler’s wealth and power depended on tribute from elites and allies. Elites supplied warriors and laborers, horses and cattle. Allies sent foodstuffs, soldiers, and workers and “assisted in the king’s affairs”—perhaps by hunting, burning brush, or clearing land—in return for his help in defending against invaders and making predictions about the harvest. Commoners sent their tribute to the elites, who held the land as grants from the ruling family. Farmers transferred their surplus crops to the elite landholders (or to the ruler if they worked on his personal landholdings) on a regular schedule.

Tribute could also take the form of turtle shells and cattle scapulas (shoulder blades), which the Shang used for divination. Divining the future was a powerful way to legitimize the rulers’ power—and then to justify the right to collect more tribute. By placing themselves symbolically and literally at the center of all exchanges, the Shang rulers reinforced their power over others.

Society and Ritual Practice

The advances in metalworking and agriculture gave the state the resources to create and sustain a complex society. The core organizing principle of Shang society was familial descent traced back many generations to a common male ancestor. Grandparents, parents, sons, and daughters lived and worked together and held property in common, but male family elders took precedence. Women from other patrilines married into the family and won honor when they became mothers, particularly of sons.

The death ritual, which involved sacrificing humans to accompany the deceased in the next life, also reflected the importance of family, male dominance, and social hierarchy. Members of the royal elite were often buried with their full entourage, including wives, consorts, servants, chariots, horses, and drivers. The inclusion of personal servants and people enslaved by the elite among those sacrificed indicates a belief that the familiar social hierarchy would continue in the afterlife. An impressive example of the burial practices of the Shang elite is the tomb of an exceptional prominent woman, Fu Hao (also known as Fu Zi), who was consort to the king, a military leader in her own right, and a ritual specialist. She was buried with a wide range of objects made from bronze and jade (including weapons), ivory, pottery, cowrie shells that were used as currency, and a large cache of oracle bones, as well as six dogs and sixteen humans who appear to have been sacrificed to accompany her at death.

The Shang state was a full-fledged theocracy: it claimed that the ruler at the top of the hierarchy derived his authority through guidance from ancestors and gods. The Shang rulers practiced ancestral worship, which was the major form of religious belief in China during this period. Ancestral worship involved performing rituals in which the rulers offered drink and food to their recently dead ancestors with the hope that they would intervene with their more powerful long-dead ancestors on behalf of the living. In finding ritual ways to communicate with ancestors and foretell the future, rulers relied on divination, much as did the rulers in Mesopotamia at this time. Diviners applied intense heat to the shoulder bones of cattle or to turtle shells and interpreted the cracks that appeared on these objects as auspicious or inauspicious signs from the ancestors regarding the plans and actions of rulers. On these bones scribes subsequently inscribed the queries asked of the ancestors to confirm the diviners’ interpretations. Thus, Shang writing began as a dramatic ritual performance in which the living responded to their ancestors’ oracular signs.

The oracle bones and tortoise shells offer a window into the concerns and beliefs of the elite groups of these very distant cultures and often reveal to researchers how similar the worries and interests of these people were to our own concerns today. The questions put to diviners most frequently as they inspected bones and shells involved the weather—hardly surprising in communities so dependent on growing seasons and good harvests—and family health and well-being, especially the prospects of having male children, who would extend the family line.

In Shang theocracy, because the ruler was the head of a unified clergy and embodied both religious and political power, no independent priesthood emerged. Diviners and scribes were subordinate to the ruler and the royal pantheon of ancestors he represented. Ancestor worship sanctified Shang control and legitimized the rulers’ lineage, ensuring that the ruling family kept all political and religious power. Because the Shang gods were ancestral deities, the rulers were deified when they died and ranked in descending chronological order. Becoming gods at death, Shang rulers united the world of the living with the world of the dead.

Shang Writing

Once scribes and priests began etching their scripts on oracle bones for the Shang rulers, a predictable evolution took place. In the Shang archaic script of primary images (often called pictographs), the same characters were used for the same sounds in Chinese. Phonetic compounds evolved into formal written graphs, which have endured to the present in East Asia. This graphic-based writing, which is based on stroke order for the graph and which combines sound and meaning, has set China (and later Japan, Korea, and Vietnam) apart from the societies in Mesopotamia and the Mediterranean that rely on syllable- and alphabet-based writing systems.

Although Shang scholars probably did not invent writing in East Asia, they perfected it. Evidence for writing in this era comes entirely from Shang oracle bones, which were central to the political and religious authority of the Shang. Other Asian written records may have been recorded on more perishable materials, such as bamboo, that did not survive. This accident of preservation may explain the major differences between the ancient texts in China (primarily divinations on bones) and in the Southwest Asian societies that impressed cuneiform on clay tablets (primarily for economic transactions, literary and religious documents, and historical records). In comparison with the development of writing in Mesopotamia and Egypt, the transition of Shang writing from record keeping (for example, questions to ancestors, lineages of rulers, or economic transactions) to literature (for example, myths about the founding of states) was slower. Shang rulers initially monopolized control over writing through their scribes, whose writing was primarily in support of Shang political and social power. Priests wrote on the oracle bones to address the otherworld and gain information about the future so that the ruling family could remain at the center of the political system.

As Shang China cultivated developments in agriculture, ornate bronze metalworking, and divinatory writing on oracle bones, the state continued to face waves of pastoral nomadic invaders, as seen in other parts of Afro-Eurasia, but on a much smaller scale. Hence, the Shang were influenced by the chariot culture that eventually filtered throughout East Asia; for the Shang, however, chariots primarily served ceremonial purposes. Given that so many of the developments in Shang China bolstered the authority of the rulers and the aristocratic elite, it is perhaps not surprising that the chariot in China was initially more a marker of elite status than an effective tool for warfare, which it became under the succeeding Zhou dynasty.

Glossary

- oracle bones

- Animal bones inscribed, heated, and interpreted by Shang ritual specialists to determine the will of the ancestors.