2 Rivers, Cities, and First States, 3500–2000 BCE

Before You Read This Chapter

GLOBAL STORYLINE

COMPARING FIRST CITIES

- Complex societies form around five great river basins.

- Early urbanization brings changes, including new technologies, monumental building, new religions, writing, hierarchical social structures, and specialized labor.

- Long-distance trade connects many of the Afro-Eurasian societies.

- Despite impressive developments in urbanization, most people live in farming villages or in pastoralist communities.

CHAPTER OUTLINE

FOCUS QUESTIONS

- Where did the world’s earliest river-basin societies arise, why did they develop there, and how were they alike and different?

- What religious, social, and political developments accompanied early urbanization from 3500 to 2000 BCE, and why did they occur?

- Where did long-distance connections develop across Afro-Eurasia during this period, and what influences did they have on the early societies?

- How did early urbanization compare with the way of life in small villages and among pastoralists?

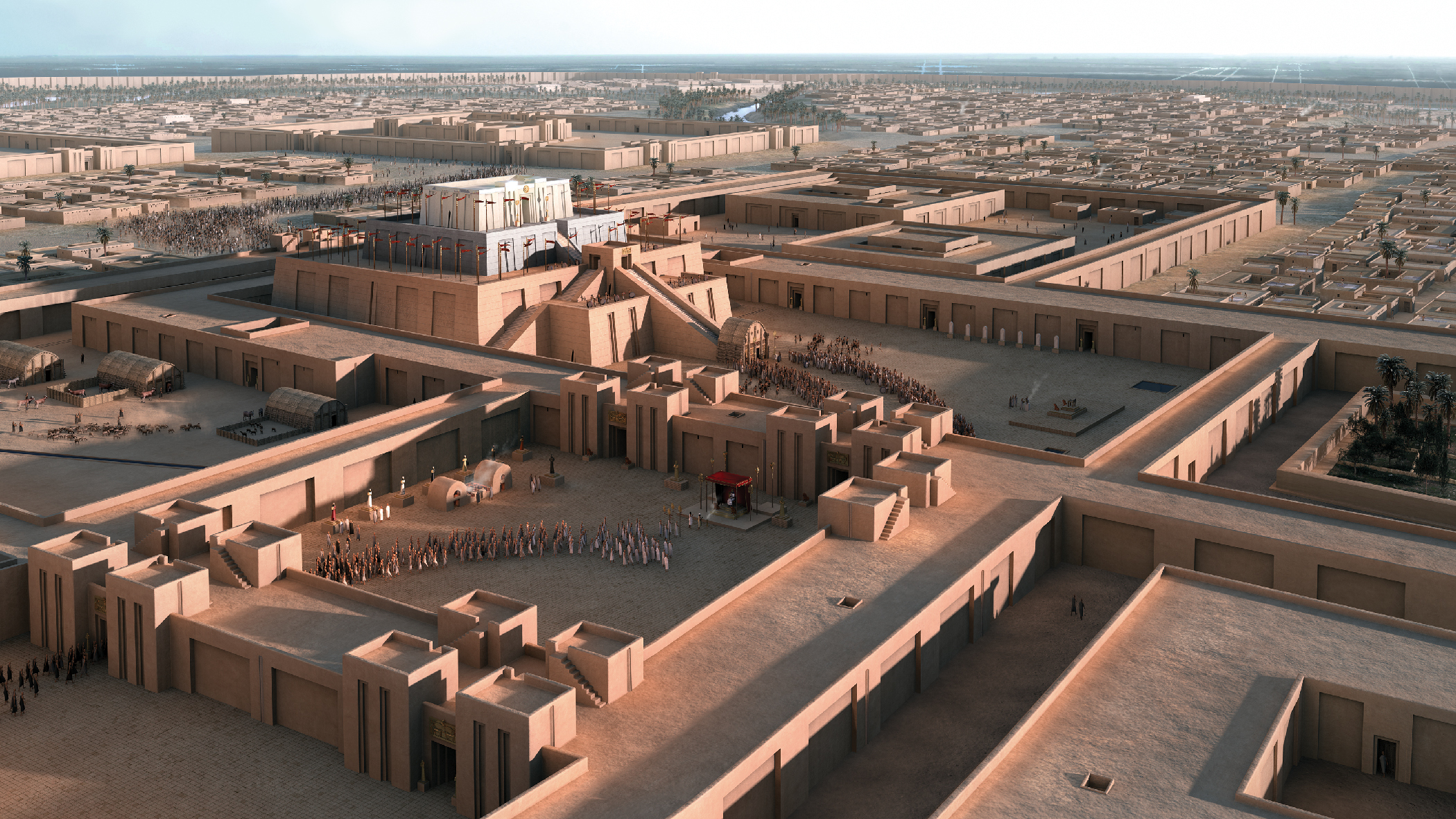

One of the first urban centers in the world was the ancient city of Uruk. Located in southern Mesopotamia on a branch of the Euphrates River, its urban area encompassed 600 acres and was home to between 25,000 and 50,000 people by the second half of the fourth millennium BCE. Flourishing between 3500 and 3100 BCE, Uruk boasted many large public structures and temples. One temple had stood there almost from the outset, erected to house and honor the city’s patron deity Inanna (the goddess of love and fertility, as well as war and political power). With a lime-plastered surface of niched mud-brick walls that formed stepped indentations, Inanna’s temple perched high above the plain. In another sacred precinct, administrative buildings and temples adorned with elaborate facades stood in courtyards defined by tall columns. Colored stone cones arranged in elaborate geometric patterns covered parts of these buildings. An epic poem devoted to its later king, Gilgamesh, described Uruk as the “shining city.”

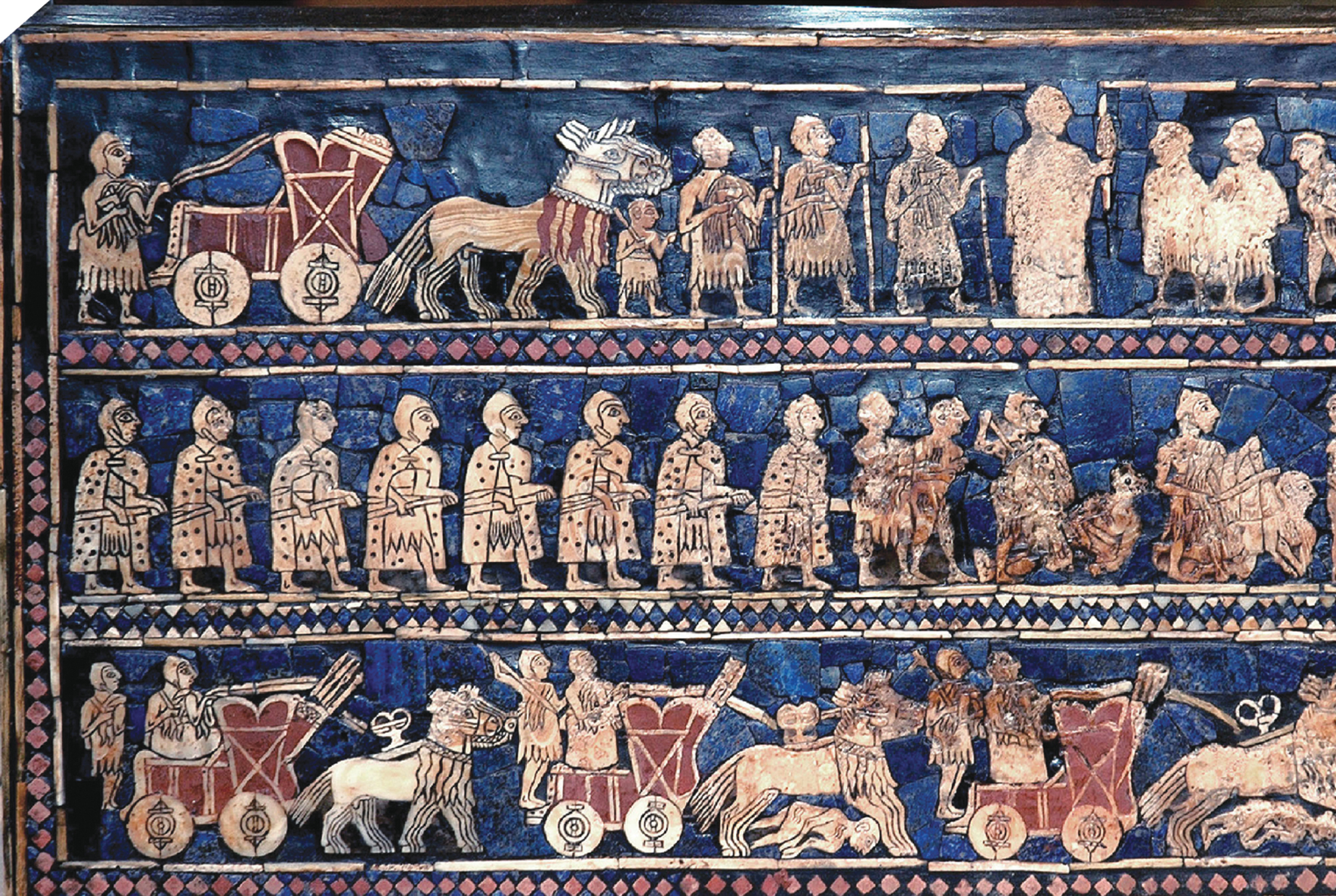

Over the years, Uruk became an immense commercial and administrative center. A huge wall with seven massive gates surrounded the metropolis, and down the middle ran a canal carrying water from the Euphrates. On one side of the city were gardens, kilns, and textile workshops. On the other side was the temple quarter where priests lived, scribes kept records, and the lugal (“big man” in the Sumerian language) conferred with the elders. As Uruk grew, many small industries became centralized in response to the increasing sophistication of construction and manufacturing. Potters, metalsmiths, stone bowl makers, and brickmakers all worked under the city administration.

As the first city in world history, Uruk marked a new phase in human development. Earlier humans had settled in small communities scattered over the landscape and lived close to nature. From 10,000 BCE to 5000 BCE, some of them learned how to farm and herd, which they combined with hunting and gathering. Gradually, however, some communities attracted large populations and grew into cities. An important marker of city life was the high wall that encircled the city and made clear that the city, unlike the town, was a constructed community whose inhabitants removed themselves from the natural world for the first time. Not only did these cities become focal points for trade, but they also created institutions for asserting economic, religious, and political power. Many city dwellers, though hardly the majority, no longer produced their own food, working instead in specialized professions.

Between 3500 and 2000 BCE, a handful of remarkable societies clustered in a few river basins on the Afro-Eurasian landmass. These regions—in Mesopotamia (between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers), in northwest India (on the Indus River), in Egypt (along the Nile), and in China (near the Yangzi and Yellow Rivers)—became the heartlands for densely populated settlements with complex cultures. Here the world saw the birth of the first large cities that exhausted surrounding regions of their resources. One of these settings (Mesopotamia) brought forth humankind’s first writing system, and all laid the foundations for kingdoms radiating out of opulent cities. This chapter describes how each society evolved, and it explores their similarities and differences. It is important to note how exceptional these large city-states were. The cities of Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus Valley, and China were in reality “miniscule affairs both demographically and geographically . . . a mere smidgeon on the map of the ancient world and not much more than a rounding error in a total population estimated at roughly twenty-five million in the year 2000 BCE” (Scott, p. 14). We will see that many even smaller societies prevailed elsewhere. The Aegean, Anatolia, western Europe, the Americas, and sub-Saharan Africa offer reminders that most of the world’s people dwelt in small communities, far removed culturally from the monumental architecture and accomplishments of the big new states. Nevertheless, cities were a transformative development because their power put other societies in peril and motivated them to catch up or perish.