Early Religious Divisions

The Origins and Spread of Islam

Islam arose on the Arabian Peninsula, in what is today Saudi Arabia. Despite Arabia’s remoteness and sparse population, by the sixth century CE it was brushing up against exciting outside currents: long-distance trade, religious debate, and imperial politics. The Hijaz—the western region of Arabia bordering the Red Sea—was in regular contact with the outside world through trade routes reaching up the coast from the Indian Ocean on their way to the Mediterranean. Mecca, located in the Hijaz, was an unimposing village of simple mud huts. Mecca’s inhabitants included both merchants and the caretakers of a revered sanctuary called the Kaaba, the dwelling place of hundreds of deities venerated by the local polytheistic Arab tribes. In this small town in this remote region, one of the world’s major prophets emerged, and the universalizing faith he founded eventually became the fastest-growing religion in the contemporary world.

A Vision, a Text

Muhammad was born around 570 CE into a well-respected tribal family in Mecca, though he was orphaned as a child and raised by an uncle. As an adult, he enjoyed limited financial success as a trader, particularly after he married a wealthy widow, Khadija, and helped manage her affairs. But when he reached the age of forty, everything for Muhammad—and in due time for the world—suddenly changed: Muhammad received a message from God. This momentous event occurred during a monthlong spiritual retreat he had taken to a cave near Mecca. One night, Muhammad awoke to the feeling of a strong pressure on his chest, which, despite his fear, he understood to be the angel Gabriel, with a message for him from God. Addressing him in Arabic, Gabriel commanded Muhammad to recite the following words:

Recite in the Name of the Lord who created,

Created man from a clot of blood

Recite: And your Lord is the most Bounteous who teaches by the pen

Teaches man that which he did not know.

After hesitating at first, Muhammad soon found revelation pouring forth from his mouth for the first time in the language of the Arabs, whom the local Jews and Christians of Arabia had teased for having been left out of God’s divine plan. Further revelations followed over the next two decades. The early ones were like the first: short; powerful; emphasizing a single, all-powerful God (Allah in Arabic), the same God as that of the Jews and the Christians; and full of instructions for Muhammad’s followers in Mecca to carry this message to nonbelievers. The words were eminently memorable, an important feature in an oral culture where poetry recitation was the highest art form. (Muhammad himself is believed to have been illiterate.) Muhammad’s early preaching had a clear message. He urged his small band of followers to act righteously, to set aside false deities, to submit themselves to the one and only true God, and to care for the less fortunate—for the Day of Judgment was imminent. Muhammad’s most insistent message was the oneness of God, in contrast to the polytheism practiced by most Arabs at the time, a belief that has remained central to Islam ever since.

The Move to Medina

Although Muhammad won a few initial followers among his fellow Meccans, the town’s leadership resisted the challenge he posed to their authority. They were especially wary of his preaching about an “end of days” when only their deeds, and not their connections or wealth, would determine their fates. Facing increasing hostility, Muhammad and his small group of followers fled Mecca in 622 CE, traveling northward to the city of Yathrib, known thereafter as Medina (“emigration”). The perilous 200-mile journey from Mecca to Medina, known as the hira (“emigration”), so significant in Islamic history that it marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar.

More information

An elevated view of the great mosque. A large crowd of people is outside, inside, and on the top walkway of the mosque. The mosque is a circular building with several stories and no roof. The main entrance has two high towers that extend upward and three arches in the entryway. There is a long facade in front of the mosque that has many arches and multiple entrances. The city skyline is visible behind the mosque.

Medina was the crucible for the new faith called Islam (“submission”—in this case, to the will of God) and a new community called Muslims (“those who submit”). The city of Medina had been experiencing intertribal and religious tensions, and the elders invited Muhammad and his followers to take up residence there in the hope that Muhammad’s charismatic leadership would bring peace and unity to their city. Early in his stay, Muhammad drew on the pragmatic business mindset he no doubt had acquired from years of working as a merchant to put forth the Constitution of Medina. This document laid down rules intended to promote harmony among the different groups in the city (including its Muslim, Jewish, and pagan inhabitants), in part by requiring that all unresolvable disputes be referred to God and Muhammad. Traditional bonds of family, clan, and tribe were thus replaced with belonging through faith. In this way, Medina produced a new form of communal unity: the umma (“band of the faithful”).

Muhammad continued to receive revelations over the course of twenty-two years. These were recorded by his companions on whatever material could be had (including the shoulder blades of camels, parchment, stones, and palm fronds) and were compiled into an authoritative version after the Prophet’s death. They formed the foundational text of Islam: the Quran (which literally means “recitations”). Its 114 chapters, known as suras, occur not in chronological or thematic order, but in descending order of length; the longest has 300 verses and the shortest, a mere 3. Accepted as the very word of God, they were believed to have passed without flaw from God through his perfect instrument, the Prophet Muhammad. Muhammad believed that he was a prophet in the tradition of Moses, other Hebrew prophets, and Jesus and that he communicated with the same God that they did. The Quran, along with the record of Muhammad’s own words, deeds, habits, and decisions during his lifetime (known in Arabic as hadith), constituted the tenets of a new faith intended to unite a people and to expand Islam’s spiritual and political frontiers.

Over time, the core practices and beliefs incumbent upon every Muslim would crystallize as the five pillars of Islam. Muslims were expected to (1) proclaim strict monotheism by reciting the phrase “there is no God but God and Muhammad is His Messenger”; (2) pray five times daily facing Mecca; (3) fast from sunup until sundown during the month of Ramadan; (4) travel on a pilgrimage (or hajj) to Mecca at least once in a lifetime if their personal resources permitted; and (5) pay alms in the form of taxation that would alleviate the hardships of the poor. These clear-cut expectations gave the imperial system that would soon develop around Islam a clear doctrinal and legal structure that held broad appeal to diverse populations, particularly those with some previous exposure to monotheism.

Muhammad’s Successors and the Expanding Dar al-Islam

In 632 CE, Muhammad died of natural causes, but Islam remained vibrant thanks to the energy of the early followers—especially Muhammad’s first four successors, the “rightly guided caliphs.” The Arabic word khalīfa means “delegate,” and in this context it referred to Muhammad’s successors as political rulers over the Muslim community as well as the expanding Islamic empire, even though the era of revelation had come to an end with Muhammad’s death. Their goal was to institutionalize the new faith and help it spread. But all was not smooth in establishing the line of succession. The community of believers disagreed over who should take Muhammad’s place and how such decisions should be made in order to best preserve communal cohesion. Some felt that the line of authority should pass exclusively through Muhammad’s family. Others thought the successors should be Muhammad’s closest companions. The conflicts associated with the process of selecting the first four caliphs left a permanent rupture in the nascent religion; to this day, the divisions originating from this period of internal strife represent one of the greatest challenges to Islam’s efforts to create a unified community of believers.

SUNNIS AND SHIITESThe questions that fueled these disagreements were who should succeed the Prophet, how the succession should take place, and who should lead Islam’s expansion into the wider world. The vast majority of Muslims today are Sunnis (from the Arabic word meaning “tradition”). They accept that the political succession to the Prophet through the four rightly guided caliphs and then to the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties was the correct one.

Shiites (“members of the party of Ali”) disagree. They believe that the proper successor to Muhammad should have been Ali, followed by Ali’s direct descendants. Ali, after all, was the Prophet’s cousin and had married his daughter Fatima. He was also one of the earliest converts to Islam and was part of the band of Meccans who had migrated with the Prophet to Medina. Although Ali did in fact serve as the fourth of the rightly guided caliphs, ruling from 656 to 661 CE, he was assassinated as he was praying in a mosque in Kufa, Iraq. His sons, Hassan and Hussein, met a similar end when they tried to avenge their father’s death. As a result of these martyrdoms, Shiism split off to become Islam’s most potent dissident force. Over time, the division between Sunnis and Shiites grew in doctrinal terms as well. Each group developed its own approach to sharia (Islamic law), its own collections of trustworthy hadith, and its own theological tenets. Muslims shared a reverence for a single God and a basic Arabic text (the Quran traditionally cannot be translated, so all Muslims study it in its original language), but sometimes they had little else in common. Religious and political differences multiplied as Islam spread into new corners of Afro-Eurasia where it assimilated a wide variety of different cultural attributes, though its basic message remained the same.

Sunni Islam continued to develop under the Umayyad caliphate. The Umayyads had laid claim to the caliphate upon Ali’s death and moved out of Arabia to the Syrian city of Damascus, where they had served as governors when Ali was still caliph. Under Umayyad rule a new form of leadership emerged in Islam: the hereditary monarchy, meant to resolve disputes associated with choosing leaders by consensus. This structure assured that Arabs, not to mention members of the Umayyad family itself, would maintain a privileged position in the caliphate even as the Umayyad conquests brought all kinds of new populations under the authority of the caliphate. Because the Quran forbade forced conversion, the majority population of the expanding Islamic empire remained non-Muslim for several centuries, with only the potential benefits of joining the religion of the ruling class to compel people to convert. Islam developed sophisticated institutions to deal with this situation, ultimately granting non-Muslims, including Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians, the legal right to continue to practice their own religions as long as they observed certain restrictions, like not ringing church bells loudly or harboring spies. They also had to pay a special tax, known as the jizya. Yet even those who converted to Islam were not always treated equally by the Umayyads. Non-Arabic-speaking converts were not allowed to hold high political offices under the Umayyads, an exclusive policy that contributed to the dynasty’s ultimate demise as more Persians in particular converted to Islam. The Umayyads set the new religion on the pathway to imperial greatness and linked religious uprightness with territorial expansion, empire building, and an appeal to all peoples. (See Current Trends in World History: The Origins of Islam in the Late Antique Period: A Historiographical Breakthrough.)

FATIMIDS After 300 years in opposition, Shiites finally managed to seize a measure of power for themselves. Oppressed in the Abbasid heartlands of Iraq and Iran, Shiite activists made their way in the early tenth century CE to North Africa, where they joined with dissident Amazigh (“Berber”) groups to topple local Sunni rulers. In 909 CE, they established a foothold in what is today Tunisia, thus marking the beginning of the Fatimids, their name an indication of the group’s lineage tracing back to Fatima, the daughter of Muhammad and the wife of Ali, Shiism’s first martyr. Fatimid rule would eventually expand to include much of North Africa, Sicily, Sudan, and the Levant (Southwest Asia), and even parts of the Hijaz. But the Fatimids left their most enduring mark on Egypt, which they conquered in 969 CE, in direct challenge to the Abbasid caliphs of Baghdad. The Fatimids refused to recognize Abbasid authority, claiming that they, and not the caliphate, spoke for the whole Islamic world. The Fatimid rulers established their capital in a new city that arose alongside the Nile River in al-Fustat, the old Umayyad capital. They called this place al-Qahira (or Cairo), “the Victorious,” and promoted its beauty in every possible way. Early on they founded a monumental place of worship and learning, al-Azhar, which attracted scholars from all over Afro-Eurasia and spread Islamic learning far and wide; they also built other elegant mosques and centers of learning. The Fatimid regime lasted until the late twelfth century. Though its rulers made little headway in persuading the Egyptian population to embrace their Shiite beliefs, the Fatimids’ cultural imprint is visible on the Cairo cityscape to today.

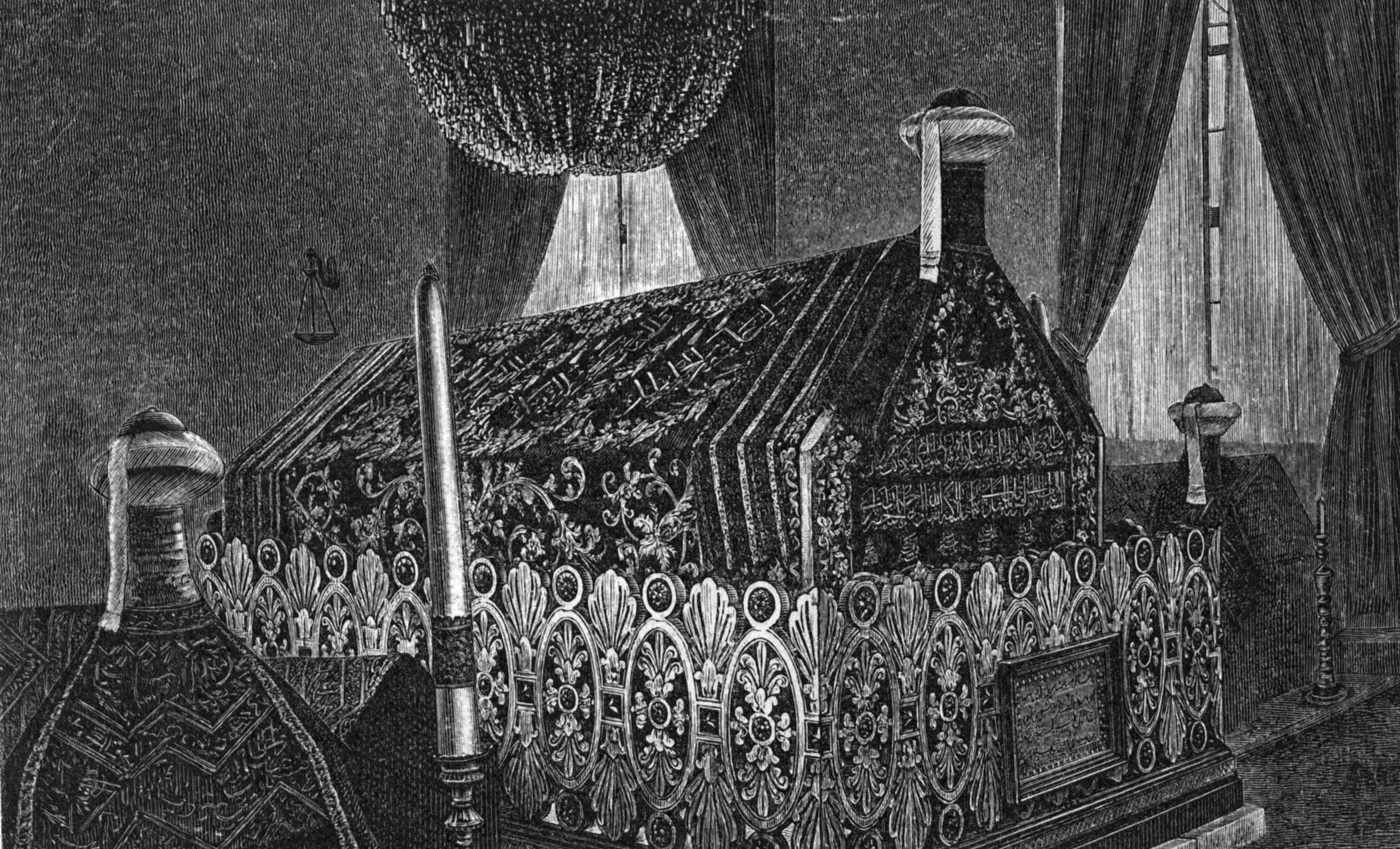

More information

An etching of the tomb of the Prophet Muhammad. The tomb is covered in ornate patterns and has a plaque on the front. Two smaller tombs sit on either side of the center tomb. A candlestick is in the foreground of the etching and an upside down dome hangs above the center tomb. Two large windows with curtains are visible behind the tombs.

By 1000 CE, Islam, which had originated as a radical religious revolution in a small corner of the Arabian Peninsula, had grown into a vast political empire. It had become the dominant political and cultural force in the middle regions of Afro-Eurasia. Like its main rival in this part of the world, Christianity, it aspired to universality. But unlike Christianity, it was linked from the beginning to political power. Muhammad had been an astute political leader, and his early followers created an empire to facilitate the expansion of their faith; Jesus never held worldly power, and Christianity inherited an empire only when Constantine embraced the faith. A vision of a world under the jurisdiction of Muslim caliphs, adhering to the dictates of sharia, inspired Muslim armies, merchants, and scholars to venture to territories thousands of miles away from Mecca and Medina. Yet the impulse to expand ran out of energy at the fringes of Islam’s reach, creating political fragmentation in the Muslim world and leaving much of western Europe and China untouched. But it also had important internal consequences: by 1000 CE, Muslims were no longer the minority within their own vast lands, owing to the conversion over time of Christians, Jews, and other populations living under Muslim rule.

The expansion of Islamic rule was one aspect of the struggle called jihad. Muslim leaders divided the world into two units: the dar al-Islam (or the world of Islam) and the dar al-harb (the world of warfare). Toward the end of his lifetime, Muhammad had been able to return to Mecca and conquer it once and for all, rededicating the Kaaba to the one God and ensuring that all of Arabia would fall under Islamic rule. Within fifteen years of his death, Muslim armies had taken Syria, Egypt, and Iraq—centerpieces of the former Byzantine and Sasanian Empires that now solidified an even larger Islamic empire. Mastery of desert warfare and inspired military leadership yielded these astonishing exploits, as did the exhaustion of the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires after generations of warfare. The Byzantines saved the core of their empire by pulling back to the highlands of Anatolia, where they had readily defensible frontiers. In contrast, the Sasanians gambled all, hurling their remaining military resources against the Muslim armies, only to be crushed. Having lost Iraq and lacking the strength to defend the Iranian plateau, the Sasanian Empire passed out of existence.

Difficulties in Documentation

Unfortunately, we have almost no Arabic sources written by seventh-century CE Muslims about Muhammad and the development of early Islam. While non-Muslim sources, especially Christian and Jewish texts, are more abundant and contain useful data on the Prophet and the rise of Islam, they often are biased against Muhammad and his mission. Many of these sources, as well as the Quran itself, stress the end-times content of Muhammad’s preaching and the actions of his followers. The conclusion that scholars derive from these sources is that it was only during the eighth century CE, in the middle of the Umayyad period, that Islam lost its end-of-the-world emphasis and settled into a long-term religious and political system.

Current Trends in World History

The Origins of Islam in the Late Antique Period: A Historiographical Breakthrough

The recent explosion of historical writing on the origins of Islam owes an enormous debt to the creation of the field of Late Antiquity, in particular the 1971 publication of Peter R. Brown’s pioneering work The World of Late Antiquity, AD 150 to 750. Although the book predated the surge in world history studies, it was part of a powerful globalist impulse to create new chronologies and new geographies. Its impact compelled scholars of classical and Islamic history to expand their research boundaries as well as their linguistic abilities.

Late Antiquity, according to Brown, was characterized by cultural Hellenism, centered in the Mediterranean basin. While Christianity was a decidedly new religion, Christian theologians and philosophers like Origen, Athanasius, and Augustine employed Hellenic thought to assimilate Christianity to the Hellenism of the Greco-Roman world. Brown similarly recognized Islam’s incorporation of Mediterranean ideas. The newly Islamized Arabs, spilling out of the Arabian Peninsula, created an empire like that of the Roman-Byzantine and Sasanian Empires, even assimilating many Byzantine and Sasanian practices and preserving and adding to Greek learning, a heritage that they passed on to Europe at the time of the Renaissance. According to Brown, “The religion of Islam . . . [was] the most rapid crisis in the religious history of the Late Antique period.” In another work, he added that “early Islam trembled on the brink of becoming (like its ancestors—Judaism and Christianity) a Mediterranean civilization.” For Brown, the true end of the Late Antique period came only in 750 CE with the foundation of the Abbasid dynasty. Islam’s new capital at Baghdad (rather than the more Mediterranean-oriented Umayyad capital in Damascus), along with its thrust eastward into Iran and farther east into Khurasan, turned Islam away from the Mediterranean basin and its Greco-Roman culture and institutions.

Brown’s challenge to Islamicists was to determine whether Islam in the first century of its existence was in fact an extension of Late Antiquity, and not a break with the past. In truth, historians of Islam were slow to accept the challenge, noting that other than the Quran itself, most of what we know about Islam’s first two centuries comes from Muslim sources written in the eighth, ninth, and even tenth centuries CE. But in reality, there was a substantial non-Muslim literature on the origins of Islam that, in spite of biases against Islam, contained vital information on its origins.

Nearly four decades after Brown issued his challenge, classicists and Islamicists started exploring the beginnings of Islam using non-Muslim sources, including Greek, Armenian, Aramaic, Latin, Hebrew, Samaritan, Pahlavi, Syriac, and Arabic texts. Now scholars have revised our understanding of Muhammad’s career, the emergence of a monotheistic creed in the Arabian Peninsula, and the Arabs’ aspiration to create a universal empire. One of these scholars, Aziz al-Azmeh, has asserted that the birth of Islam was not a rupture with earlier traditions but “an integral part of late antiquity.” An important finding from these new sources is that when Islam arose, Jews and Christians were welcomed into the umma and some became Muhammad’s early followers. Moreover, as the Arabs expanded out of the Arabian Peninsula into Syria, Iraq, and Egypt, they did not necessarily see themselves as carrying a “new” religion. As monotheists, they recognized their similarities with Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians and welcomed alliances with them. Islam did not emerge as a separate confessional religion, with many of the features that exist today, until the reign of the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (r. 685–705 CE). Coins minted in Abd al-Malik’s name and numerous inscriptions in the Dome of the Rock, a building constructed in 692 CE in Jerusalem under his auspices, make clear the distinctiveness of Islam from Christianity and Judaism by this period.

Sources: Peter R. Brown, The World of Late Antiquity, AD 150 to 750 (London: Thames & Hudson, 1971; reprint as Norton Paperback, 1989), p. 189; Peter R. Brown, Society and the Holy in Late Antiquity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982), p. 68; Aziz al-Azmeh, The Emergence of Islam in Late Antiquity: Allah and His People (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2014), pp. 2–3.

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- How did Brown’s World of Late Antiquity pose a challenge to scholars of early Islam?

- Why do you think scholars of Islam were slow to respond to Brown’s challenge?

- How has the understanding of Islam’s beginnings changed with the contributions of recent scholarship?

EXPLORE FURTHER

Armstrong, Karen, Islam: A Short History (2002).

al-Azmeh, Aziz, The Emergence of Islam in Late Antiquity: Allah and His People (2014).

Bowersock, G. W., The Crucible of Islam (2017).

Crone, Patricia, Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam (2004).

Donner, Fred M., Muhammad and the Believers at the Origins of Islam (2010).

Hoyland, Robert G., In God’s Path: The Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire (2015).

Robinson, Chase F., ‘Abd al-Malik (2005).

Shoemaker, Stephen J., The Death of a Prophet: The End of Muhammad’s Life and the Beginnings of Islam (2012).

The only Muslim source on Muhammad and early Islam that has survived to our day is the Quran itself, which, according to Muslim tradition, was compiled during the caliphate of Uthman (r. 644–656 CE). Recent scholarship has questioned this claim, suggesting a later date, sometime in the early eighth century CE, for the standardization of the Quran. Some scholars even contend that the text by then contained additions to, and redactions of, God’s message to Muhammad. The Quran, in fact, is quiet on some of the most important events of Muhammad’s life. It mentions the name of Muhammad only four times. For more information, scholars have depended on biographies of Muhammad, one of the first of which was compiled by Ibn Ishaq (704–767 CE); this work does not survive in its original form, but it can be found in works by later Muslim authorities, notably Ibn Hisham (d. 833 CE), who wrote The Life of Muhammad, and Islam’s most illustrious early historian, Muhammad al-Tabari (838–923 CE). Although the works of these later writers come from the ninth and tenth centuries CE, Muslim tradition ever since has held these sources to be reliable on Muhammad’s life and the evolution of Islam after the death of the Prophet.

The Abbasid Revolution

With the establishment of its capital at Damascus, the Umayyad dynasty had succeeded in exporting Islam beyond Arabia. However, the fact that the Umayyads continued to privilege ethnic Arabs like themselves even as the Muslim community grew more diverse caused resentment among many new converts to Islam, especially because Muhammad had preached the equality of all Muslims. For example, the Umayyads had enslaved large numbers of non-Arabs in the course of their conquests. These enslaved people could shed their servile status through manumission. But non-Arab freed people who converted to Islam found that they were still regarded as lesser persons although they lived in Arab households and had become Muslims. This situation persisted even though ethnic Arabs totaled only about 250,000 to 300,000 during the Umayyad era, while non-Arab populations were 100 times as large, totaling between 25 and 30 million. Protest against Arab domination reached a crescendo in central Asia, notably in Khurasan, which included portions of modern-day Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan. In Khurasan, most of the Arab conquerors did not live separately from the local populations in garrison cities (as was commonplace elsewhere) but were in close contact and intermarried with indigenous Persian, Turkic, and Kurdish women. One of the early leaders of the protest movements in Khurasan was Abu Muslim, who fought for Islam’s universality to be recognized, with equality for all Muslims. Although he himself was Persian, he did not claim his heritage through any ethnic group, but instead asserted that he descended from Islam, as his name indicates.

Even though opponents assassinated Abu Muslim, they did not silence his message. A coalition of dissidents emerged under a movement that harkened back to Abbas Ibn Abd al-Muttalib (568–653 CE), an uncle of the Prophet. This Abbasid movement, named for Muhammad’s uncle, thus claimed descent from the Prophet. Soon disgruntled provincial authorities and their military allies, as well as non-Arab converts, joined the Abbasids. After amassing a sizable military force, they trounced the Umayyad ruler in 750 CE. Thereafter, the center of the caliphate shifted to Iraq (at Baghdad; recall the opening anecdote about al-Mansur), signifying an eastward pivot of the Islamic empire. This seismic shift represented a success for non-Arab groups within Islam without eliminating Arab influence either at the dynasty’s center—the capital, Baghdad, in Arabic-speaking Iraq—or within Islam itself, where the Arabic language and culture of the Prophet remained the ideal. But this process undoubtedly changed the nature of the emerging empire. For as the political center of Islam moved out of Arabia to Syria (at Damascus) and then with the Abbasids to Baghdad, ethnic and geographical diversity replaced what had been ethnic purity. Thus, even as the universalizing religion strove to create a common spiritual world, based on Arabic scripture delivered through an Arab prophet, it became increasingly diverse.

Not only did the Abbasids open Islam to Persian peoples, but they also embraced Greek and Hellenistic learning, Indian science, and Chinese innovations. In this fashion, Islam, drawing its original impetus from the teachings and actions of a prophetic figure, followed the trajectory of Christianity and Buddhism and became a faith with a universalizing message and appeal. It owed much of its success to its ability to merge the contributions of vastly different geographical and intellectual territories into a rich yet unified culture. (See Map 9.1.)

GOVERNANCE An early challenge for the Abbasid rulers was to determine how traditional they could be and still rule so vast an empire. They chose to keep the bedrock political institution of the early Islamic polity—the caliphate (the line of political leaders reaching back to Muhammad). Although the caliphs exercised political and spiritual authority over the Muslim community, they were not understood to have inherited Muhammad’s prophetic powers. Muhammad was the final prophet, known as the “seal” of prophecy. Nor were the caliphs authorities in religious doctrine. That power was reserved for professional scholars, called ulama.

Abbasid rule borrowed practices from successful predecessors in its mixture of Persian absolute authority and the royal seclusion of the Byzantine emperors who lived in palaces far removed from their subjects. This blend of absolute authority and decentralized power involved a delicate and ultimately unsustainable balancing act. As the empire expanded, it became increasingly decentralized politically, enabling wily regional governors and competing caliphates in Spain (like the Umayyads) and Egypt (like the Fatimids) to assert their independence. Even as Islam’s political centers multiplied, though, its spiritual center remained fixed in Mecca, where the faithful gathered to circle the Kaaba and to reaffirm their devotion to Islam as part of their pilgrimage obligation.

MILITARY The Abbasids, like all rulers, relied on force to integrate their empire. Yet they struggled with what the nature of that military force should be: a citizen-conscript, all-Arab force or a professional, even non-Arab, army. Meanwhile, non-Muslims generally did not serve in the military because it was considered an aspect of jihad and hence not incumbent upon them. In the early stages, leaders had conscripted military forces from local Arab populations, creating citizen armies. But as Arab populations settled down in garrison cities, the Abbasid rulers turned to professional soldiers from the empire’s peripheries. Now they recruited from Turkish-speaking communities in central Asia and from non-Arab, Amazigh peoples of North and West Africa. Their reliance on non-Arab military personnel represented a major shift in the Islamic world. Not only did the change infuse the empire with dynamic new populations, but soon these groups gained political authority. Having begun as an Arab state and then incorporated strong Persian influence, the Islamic empire now embraced Turkish elements from the pastoral belts of central Asia and Amazigh elements from North Africa.

The Global View

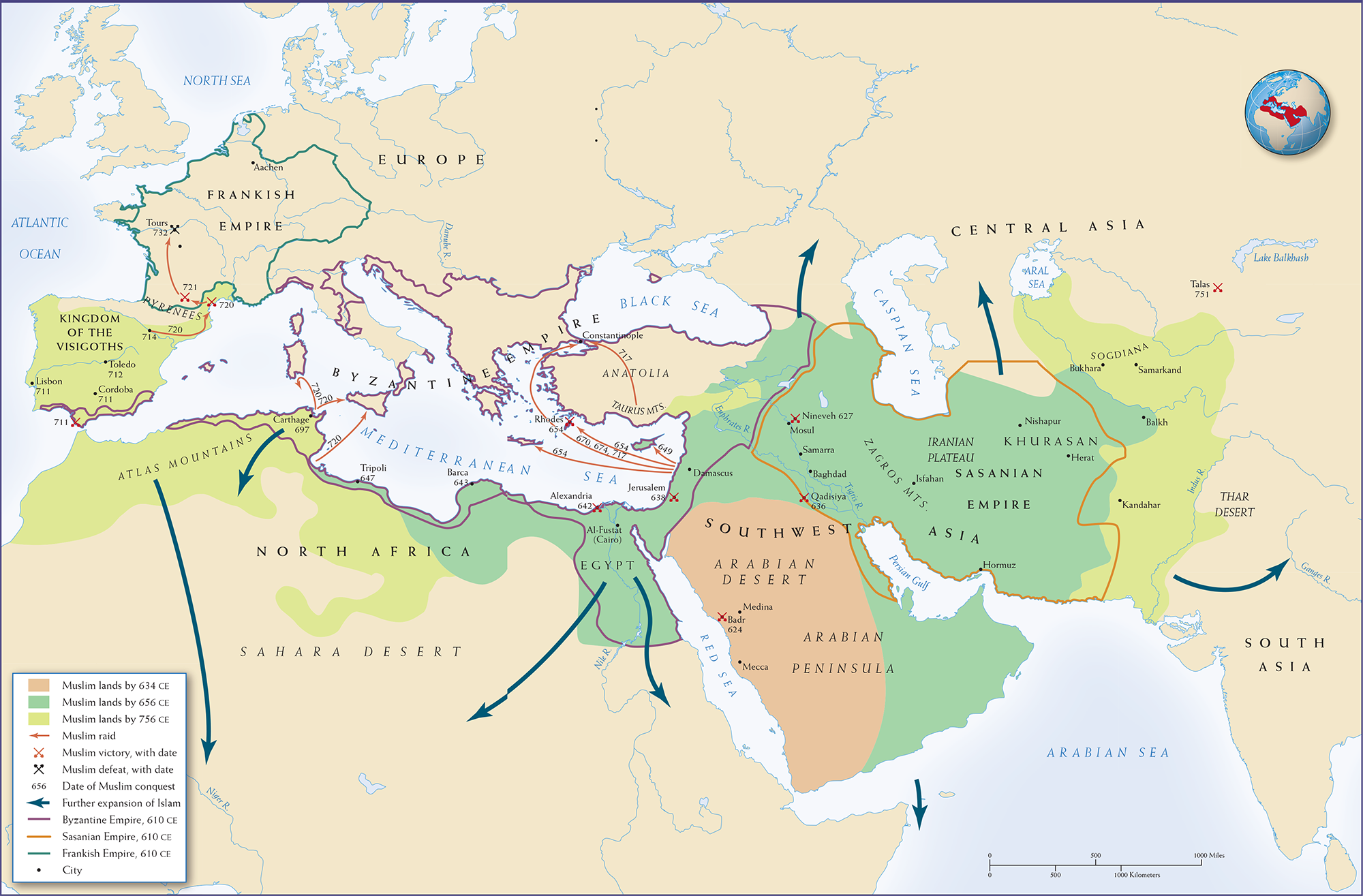

More information

Map 9.1 is titled The Spread of Islam during the First Millennium. The map shows the extent of Muslim lands at three points: 634, 656, and 756 C E, as well as the further expansion of Islam; Muslim raids, victories, defeats, and conquests (with dates); and the area of the Byzantine Empire (Turkey, Greece, Egypt, and parts of Italy, North Africa, and the Iberian Peninsula), Sasanian Empire (Iraq and Iran), and Frankish Empire (France and part of Germany) in 610 C E. By 634, most of the Arabian Desert and Peninsula were Muslim lands. By 656, all of the Sasanian Empire, Egypt, and the rest of the Arabian Desert and Peninsula were Muslim lands. By 756, western Asia, the Kingdom of the Visigoths (Spain), and much of North Africa were Muslim lands, and Muslims were raiding into the Frankish and Byzantine Empires. Muslims had victories (from West to East) in the years 711 in the Kingdom of Visigoths, 720 and 721 near the Pyrenees, 654 in Rhodes, 642 in Alexandria, 638 in Jerusalem, 624 in Badr, 636 in Qadisiya, 627 in Nineveh, and 751 in Talas River. The sole labeled defeat came in 732 in Tours. Further expansion of Islam came north on either side of the Caspian Sea, as well as into South Asia and the Horn of Africa and south across the Sahara.

LAW AND THEOLOGY Islamic law began to take clear shape in the Abbasid period. The work of generations of religious scholars, sharia covers all aspects of practical and spiritual life, providing legal principles for marriage contracts, trade regulations, and religious prescriptions such as prayer, pilgrimage rites, and ritual fasting. As Islam spread to new regions, sharia responded to regional differences on all these issues. Sharia, in its regional diversity, has remained vital throughout the Muslim world, independent of empires, to the present day.

Early Muslim communities prepared the ground for sharia, endeavoring (guided by the Quran) to handle legal matters in ways that they thought Muhammad would have wanted. The most influential early legal scholar was an eighth-century CE Palestinian-born Arab, al-Shafi’i, who insisted on institutionalizing Muhammad’s rulings as laid out in the Quran, in addition to his sayings and actions as written in later reports (hadith), arguing that the Prophet’s example provided all the legal guidance that Islamic judges needed to make their decisions.

The triumph of scholars such as al-Shafi’i was deeply significant: it placed the ulama, the Muslim scholars, at the heart of Islam. Ulama, not princes and kings, became the lawmakers, insisting that the caliphs could not define religious law. Only the scholarly class could interpret the Quran and determine which hadith were authentic. The ulama’s ascendance opened a contest within Islam: between the political realm of the caliphs and the religious sphere of judges, experts on Islamic jurisprudence, teachers, and holy men. Sunni Islam has a total of four different schools of law and jurisprudence, including the one founded by al-Shafi’i. Shiites are divided into three different sects, each following their own legal practices.

GENDER IN EARLY ISLAM Pre-Islamic Arabia was a patriarchal tribal society, with identity and status based on male-to-male relationships. Since there was no system of writing in this setting, we know very little about women’s lives there. Most of what we do know comes from later Muslim sources, which perceive the period before Muhammad as jahiliyyah, a dark age of ignorance in contrast with the more enlightened age of Islam. For example, Islamic tradition holds that Arabian tribal societies practiced female infanticide in order to not waste resources on less productive members of society, and that Muhammad outlawed the practice. Although we have no evidence to corroborate this claim, we do know with greater certainty that women engaged in a variety of occupations. We also know that at least one woman was able to inherit wealth from her deceased husband as his widow.

That woman, of course, was Khadija, Muhammad’s first wife and Islam’s first convert. She bridged the pre-Islamic and Islamic worlds as an independent female merchant trading with her inherited wealth until she married Muhammad and he took over many of her affairs. He was fifteen years her junior at the time, and he took no other wives until after she died. It was Khadija to whom he went in fear following his first revelations. She wrapped him in a blanket and assured him of his sanity. Later in life Muhammad married additional wives, some of whom were the widows of his companions. He had them adopt the practice of veiling common to some Byzantine and Assyrian women as a sign of their modesty and privacy. He married his favorite wife, Aisha, when she was only nine or ten years old. An important figure in early Islam, she was the daughter of Abu Bakr, who became the first caliph after Muhammad’s death. Since she lived closely with Muhammad, she became a major source for collecting his sayings. She was also a warrior who led Muslim armies into battle on camelback during the age of the rightly guided caliphs.

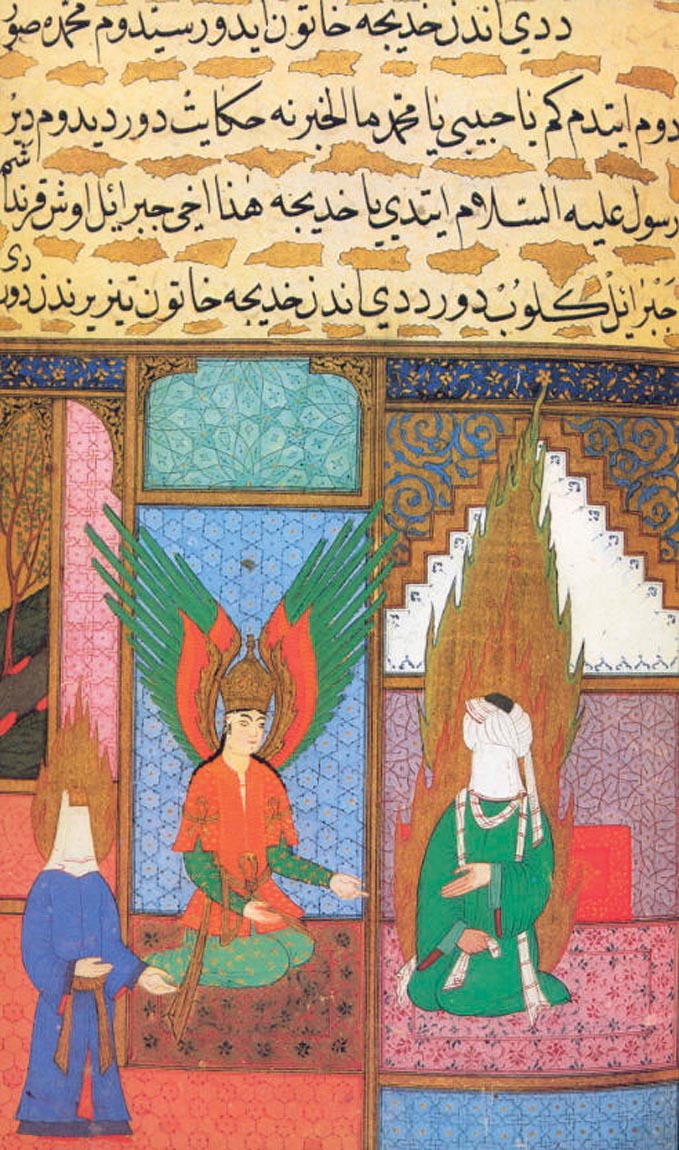

More information

A painting shows Khadija and Gabriel sitting on mattresses inside a palace while the Prophet Muhammad stands near them. The faces of the Prophet Muhammad and Khadija are obscured by blank space. Large wings extend from Gabriel’s back. There is a large pillar of flame behind Khadija and a small pillar of flame behind the Prophet Muhammad’s obscured head. There are detailed patterns on the walls, floor, and mattresses. Part of a painting with a tree in it is visible on the wall on the left side. Some text is at the top of the painting.

As Islam spread and its legal traditions evolved, women’s rights and obligations became more clearly defined. Depending on how women were treated prior to Islamic rule, its establishment could be seen as either an improvement or a downgrading of women’s status. For instance, in some places women’s inheritance rates went from nothing to half that of men with the installation of Islamic precepts. Also, Jewish women who converted to Islam went from having no right to petition for divorce to having some rights to dissolve a marriage, though still not the full freedom men enjoyed. Under Islamic law, a man could take four wives and numerous concubines; a woman could have only one husband. Still, the fact that the number of wives was limited to only four, and that a man wishing to marry more than one woman had to prove he had the resources to support them, both limited the extent of polygamy (which was practiced in Judaism at this time as well) and often resulted in an improvement on the more informal sexual arrangements that prevailed. Marriage dowries went directly to the bride rather than to her guardian, indicating women’s independent legal standing. And while a woman’s adultery drew harsh punishment, its proof required eyewitness testimony, which was rarely available. The result was a legal system that reinforced men’s dominance over women but empowered magistrates to oversee the definition of male honor and proper behavior.

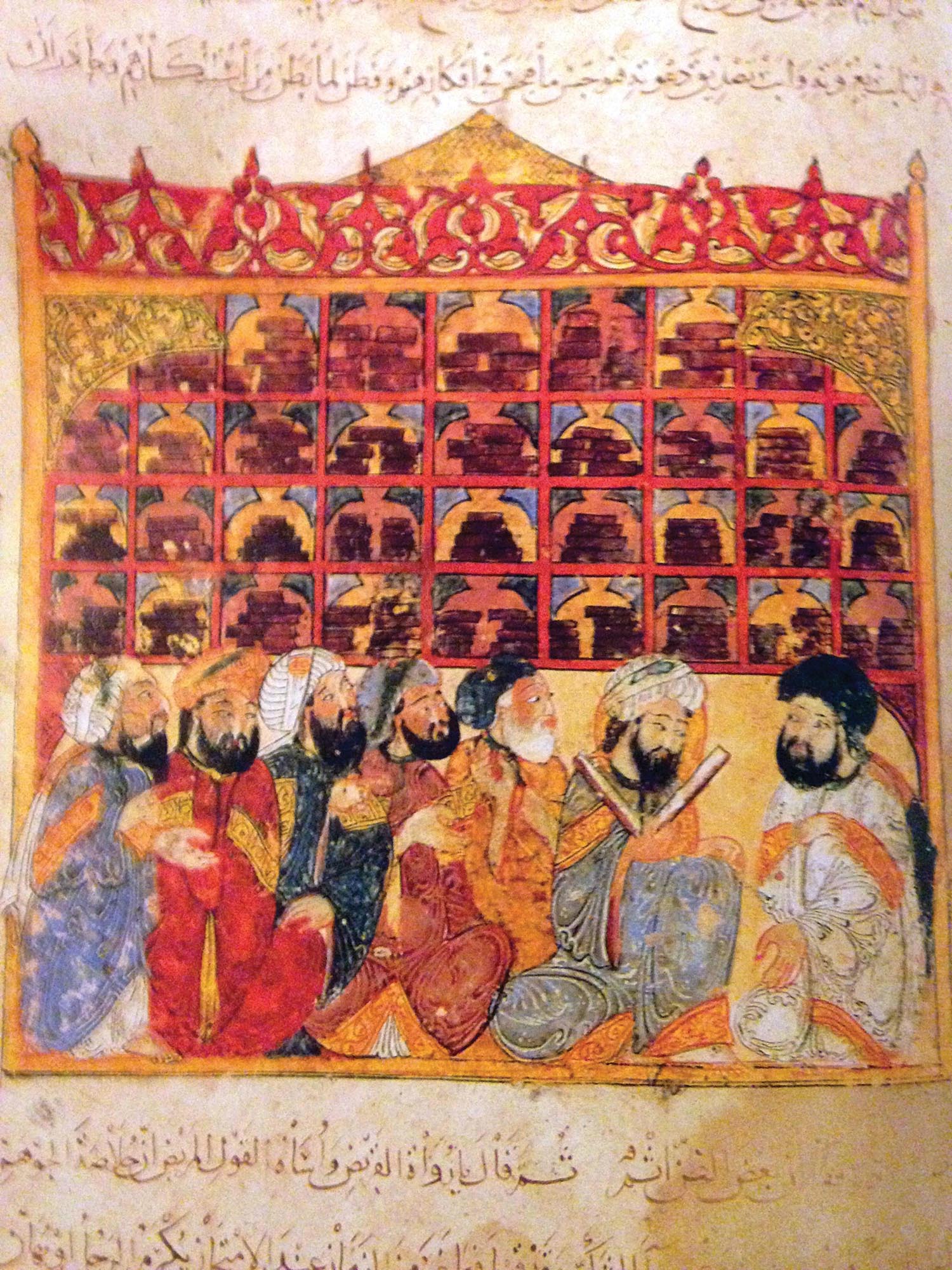

More information

An illustration of a group of men in front of a wall of cubbyholes with stacks of rectangular shapes in them. The wall behind the cubbyholes is patterned. The men have bears and wear long robes and head coverings. There is text below the illustration.

In addition to the wives of the Prophet, a number of other women stand out in early Islamic history. One of them is al-Khayzurān Bint Atta (d. 789 CE). In a pattern similar to the one we saw in the Sasanian context (see Chapter 8), al-Khayzurān worked through powerful men—her husband, the Abbasid caliph al-Mahdi (r. 775–785 CE), and her two sons who followed their father’s reign—to exert her will. The historical tradition is somewhat hostile to her, depicting her as manipulative and overly domineering in her rise from total enslavement to umm walad (unsellable mother of her enslaver’s child), to wife, and then to mother of caliphs. Her reported ruthlessness even included maneuvering her younger son, Harun al-Rashid (r. 786–809 CE), into power by having her elder son murdered. (For more on al-Rashid, see Analyzing Global Developments: Islam and the Silk Trade: Adapting Religion to Opulence.) Al-Khayzurān’s reputed influence over al-Rashid is perhaps matched by that of Zubaidah (d. 831 CE), the woman he married. Zubaidah was a well-educated woman, who went on pilgrimage to Mecca multiple times and even donated money for the construction of several wells along the hajj route between Baghdad and Mecca. Either al-Khayzurān or Zubaidah, or a blend of both, may well have been the inspiration for the learned Scheherazade, whose stories to a jilted king compose One Thousand and One Nights. Together they demonstrate how extraordinary women could assert power even within a patriarchal community.

The Blossoming of Islamic Culture

The arts flourished during the Abbasid period, a blossoming that left its imprint throughout society. Within a century, Arabic had superseded Greek as the Muslim world’s preferred language for poetry, literature, medicine, science, and philosophy. Like Greek, it spread beyond native speakers to become the language of the educated classes.

Analyzing Global Developments

More information

A statue of a person playing a pipe with one hand. Only the head and upper torso are visible. The person wears a patterned headdress and shirt or tunic with a spiked collar.

Islam and the Silk Trade: Adapting Religion to Opulence

The Silk Roads emerged from the localized industries and commercial networks of the Han, Kushan, Parthian, and Roman Empires in the first century BCE. The greatest volume of trade along this network took place over short distances, from one oasis to the next. It was not until centuries later, after the collapse of these states, that the golden age of Afro-Eurasian trade arose with new, powerful players. Tang China inherited the Han monopoly on silk production, while the Byzantine Empire utilized its Roman resources to develop its own silk weaving industry. A major threat to these monopolies appeared in the seventh century CE, when the first Islamic empire, the Umayyad caliphate (661–750 CE), built a vast, state-run textile industry to exert influence over its newly conquered cities. Not only did the establishment of textile factories throughout the empire keep the working classes in line, but the luxury textiles produced were incentives for the elite of newly conquered territories (many of which were wealthy and were more sophisticated than the Arab tent culture of early Islamic caliphs) to submit to Muslim rule.

Tensions arose between this opulent lifestyle and the more austere Muslim way of life, which discouraged its male adherents from wearing silk as well as gold. The political, social, and religious authority that the Islamic silk trade lent the caliphate, however, was crucial to its unity and longevity. What’s more, the Islamic silk industry was rapidly expanding, with no limits in sight, unlike the Byzantine and Tang silk industries, which were restricted by their respective emperors. And so this textile-centered culture proliferated in an unbridled fashion, eventually infiltrating even religious rituals. The Abbasid caliphate (750–1258 CE) became one of the wealthiest medieval states, and its capital, Baghdad, the most cosmopolitan. To illustrate the sheer extent of the impact that the Islamic silk trade had on the values of its people, the following table is a record of the goods that Caliph Harun al-Rashid, upon whom several Arabian Nights stories are based, left behind upon his death in 809 CE.

|

Textiles: Silk Items |

|

|

4,000 |

silk cloaks, lined with sable and mink |

|

1,500 |

silk carpets |

|

100 |

silk rugs |

|

1,000 |

silk cushions and pillows |

|

1,000 |

cushions with silk brocade |

|

1,000 |

inscribed silk cushions |

|

1,000 |

silk curtains |

|

300 |

silk brocade curtains |

|

Everyday Textile Items |

|

|

4,000 |

small tents with their accessories |

|

150 |

marquees (large tents) |

|

Luxury Textile Items |

|

|

4,000 |

embroidered robes |

|

500 |

pieces of velvet |

|

1,000 |

Armenian carpets |

|

300 |

carpets from Maysan (present-day east Iraq) |

|

1,000 |

carpets from Darabjird (present-day Darab, Iran) |

|

500 |

carpets from Tabaristan (southern coast of the Caspian Sea) |

|

1,000 |

cushions from Tabaristan |

|

Fine Cotton Items and Garments |

|

|

2,000 |

drawers of various kinds |

|

4,000 |

turbans |

|

1,000 |

hoods |

|

1,000 |

capes of various kinds |

|

5,000 |

kerchiefs of different kinds |

|

10,000 |

caftans (long robes) |

|

4,000 |

curtains |

|

4,000 |

pairs of socks |

|

Fur and Leather Items |

|

|

4,000 |

boots lined with sable and mink |

|

4,000 |

special saddles |

|

30,000 |

common saddles |

|

1,000 |

belts |

|

Metal Goods |

|

|

500,000 |

dinars (cash) |

|

2,000 |

brass objects of various kinds |

|

10,000 |

decorated swords |

|

50,000 |

swords for the guards and pages (ghulam) |

|

150,000 |

lances |

|

100,000 |

bows |

|

1,000 |

special suits of armor |

|

10,000 |

helmets |

|

20,000 |

breast plates |

|

150,000 |

shields |

|

300 |

stoves |

|

Aromatics and Drugs |

|

|

100,000 |

mithqals of musk (1 mithqual = 4.25 grams) |

|

100,000 |

mithqals of ambergris (musky perfume ingredient) |

|

many kinds of perfume |

|

|

1,000 |

baskets of Indian aloes |

|

Jewelry and Cut Gems |

|

|

Jewels valued by jewelers at 4 million dinars |

|

|

1,000 |

jeweled rings |

|

Fine Stone and Metal Vessels |

|

|

1,000 |

precious porcelain vessels, now called Chinaware |

|

1,000 |

ewers |

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- Looking back at Map 6.2 and assuming that the exports of each region remained relatively constant throughout the history of the Silk Roads, with which cities and empires did the Abbasid Empire conduct most of its trade? With which the least? What might account for these differences?

- What can this table tell us about the values and activities of a caliph circa 800 CE? What, if anything, does the inventory reveal about the values and activities of the nonelite or working classes?

- What kind of evidence from contemporary Tang China or western Christendom would allow you to draw comparable conclusions to arguments that can be constructed from al-Rashid’s inventory?

Arabic scholarship made significant contributions, including the preservation and extension of Greek and Roman thought and the transmission of Greek and Latin treatises to Europe. Scholars in Baghdad translated the principal works of Aristotle; essays by Plato’s followers; works by Hippocrates, Ptolemy, and Archimedes; and the medical treatises of Galen, using these works to extend their understanding of the natural world. To house such manuscripts, patrons of the arts and sciences—including the caliphs—opened magnificent libraries. The famous “house of wisdom” in Baghdad was considered the greatest repository of books in the world in the ninth century CE.

The Muslim world absorbed scientific breakthroughs from China and other areas, incorporated the use of paper from China, adopted siege warfare from China and Byzantium, and applied knowledge of plants from the ancient Greeks. From Indian sources, scholars borrowed a numbering system based on the concept of zero and units of ten—what we today call Arabic numerals. Arab mathematicians were pioneers in arithmetic, geometry, and algebra, and they expanded the frontiers of plane and spherical trigonometry. Since much of Greek science had been lost in the west and later was reintroduced via the Muslim world, the Islamic contribution to the west was of immense significance. This intense borrowing, translating, storing, and diffusing of written works, as well as the creation of them, brought worlds together.

As Islam spread and became decentralized, it generated dazzling and often competitive dynasties in Spain, North Africa, and points farther east. (See Map 9.2.) Each dynastic state revealed the Muslim talent for achieving high levels of artistry far from its heartland. As more peoples came under the roof provided by the umma, they invigorated a broad world of Islamic learning and science.

CITIES IN SPAIN One extraordinary Muslim state arose in Spain under Abd al-Rahman III (r. 912–961 CE), the successor ruler of a branch of the Spanish Umayyads founded there over a century earlier. Abd al-Rahman III brought peace and stability to a violent frontier region where civil conflict had disrupted commerce and intellectual exchange. His evenhanded governance promoted amicable relations among Muslims, Christians, and Jews, and his diplomatic relations with Christian potentates as far away as France, Germany, and Scandinavia generated prosperity across western Europe and North Africa.

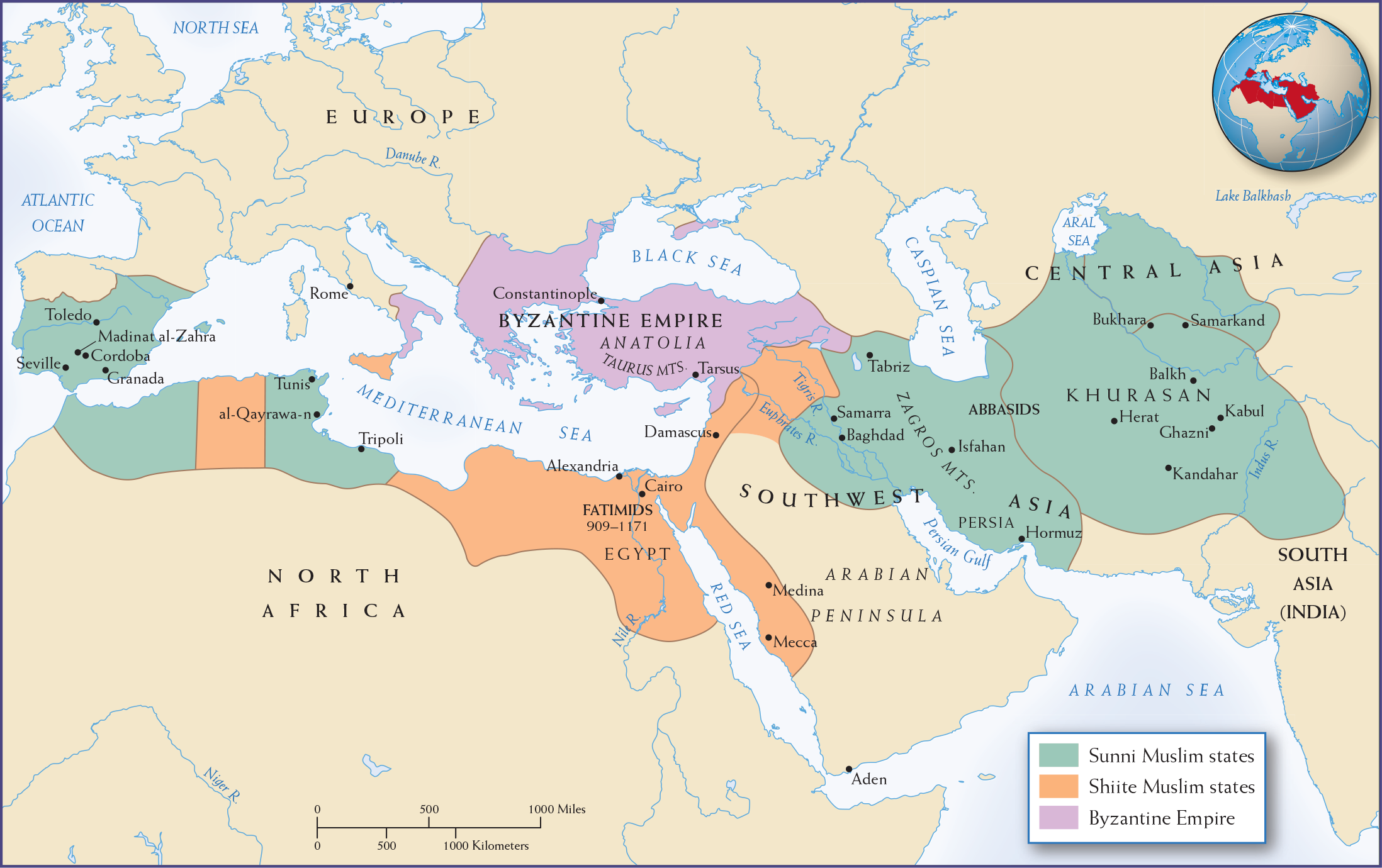

More information

Map 9.2 is titled Political Fragmentation in the Islamic World, 750 to 1000 C E. The map shows Sunni Muslim states, Shiite Muslim states, and the Byzantine Empire. The Sunni Muslim states consist of present day Iraq, Iran, and parts of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Northern India. There are also Sunni Muslim states on the southern Iberian Peninsula and parts of north-western Africa. The Shiite Muslim states consist of present day Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, Egypt, the western portions of Saudi Arabia, and between Sunni Muslim states in the north-western part of Africa. The Byzantine Empire covers Turkey, Greece, and the boot of Italy.

MAP 9.2 | Political Fragmentation in the Islamic World, 750–1000 CE

By 1000 CE, the Islamic world was politically decentralized. The Abbasid caliphs still reigned in Baghdad, but they wielded limited political authority.

- What are the regions where major Islamic powers emerged?

- What areas were Sunni? Which were Shiite?

- Looking back to empires in the Mediterranean and Southwest Asia in earlier periods, how would you compare the area controlled by Islamic rulers with the extent of the Roman Empire (Chapter 7), Hellenistic kingdoms (Chapter 6), and the Persian Empire (Chapter 4)? What do you think accounts for the differences?

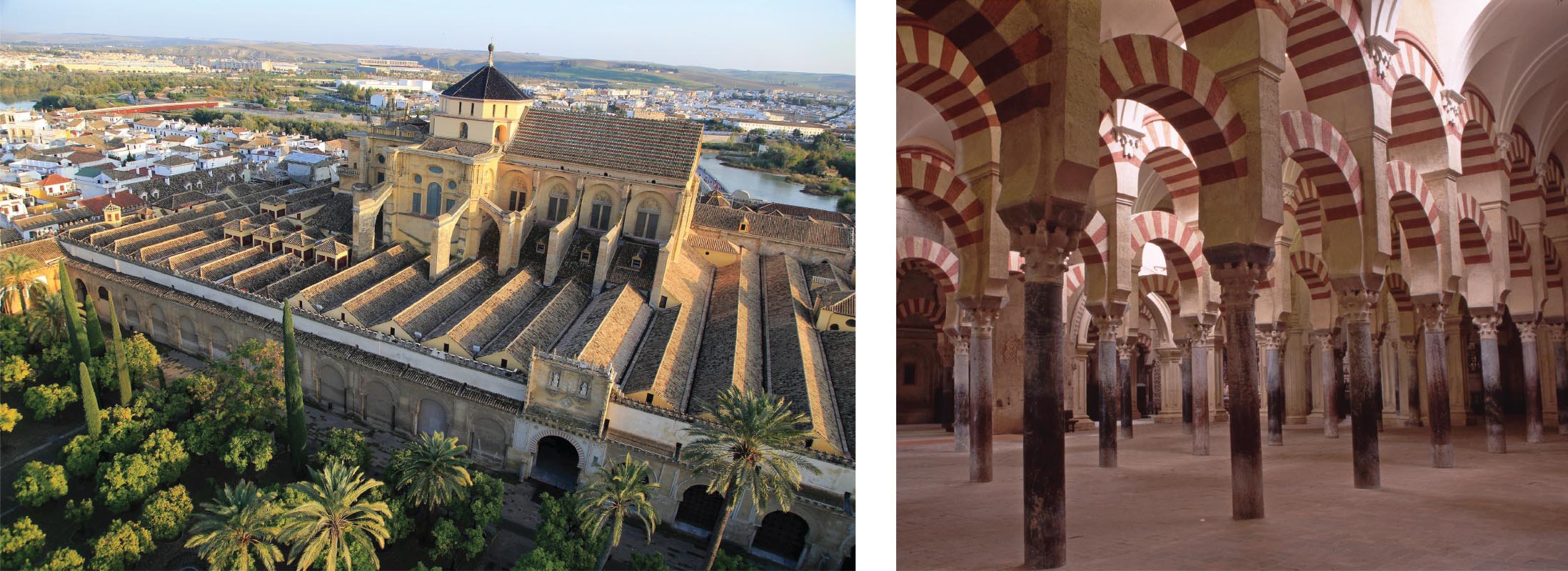

Abd al-Rahman III expanded and beautified the capital city of Cordoba, and his successors made the Great Mosque of Cordoba one of Spain’s most stunning sites. Known in Spanish as la Mezquita, the Great Mosque of Cordoba is the oldest standing mosque in Europe. Begun in 785 CE by Abd al-Rahman I, it is a stirring tribute to the architectural brilliance and religious zeal of the Muslims of al-Andalus, the Arabic name for Islamic Spain. Built in the form of a perfect square, its most striking features were alternating red and white arches, made of jasper, onyx, marble, and granite and fashioned from materials from the Roman temple and other buildings in the vicinity. These huge double arches hoisted the ceiling to 40 feet and filled the interior with light and cooling breezes. Around the doors and across the walls, Arabic calligraphy proclaimed Muhammad’s message and asserted the superiority of Arabic as God’s chosen language. In the nearby city of Madinat al-Zahra, Abd al-Rahman III surrounded the city’s administrative offices and mosque with verdant gardens of lush tropical and semitropical plants, tranquil pools, fountains that spouted cooling waters, and sturdy aqueducts that carried potable water to the city’s inhabitants.

CENTRAL ASIAN TALENT The other end of the Islamic empire, 8,000 miles east of Spain, enjoyed an equally spectacular cultural flowering. In a territory where Greek culture had once sparkled and where Sogdians had emerged as the leading thinkers, Islam was now the dominant faith and the source of intellectual ferment.

The Abbasid rulers in Baghdad delighted in surrounding themselves with learned men from this region. They promoted and collected Arabic translations of Persian, Greek, and Sanskrit manuscripts, and they encouraged central Asian scholars to enhance their learning by moving to Baghdad. One of their protégés, the Muslim cleric al-Bukhari (d. 870 CE), was a dedicated collector and authenticator of hadith, which provided vital knowledge about the Prophet’s life.

More information

A bird’s eye view of the Great Mosque of Cordoba. The Great Mosque has a large central portion that is surrounded by buildings on its four sides that are smaller in size. Rows of long shorter buildings sit in front of the large central building. There is a courtyard of trees in front of the mosque and a small body of water behind it. A city sprawls in the background.

A side shot of a large open area in the Mosque of Cordoba that shows many columns in rows holding up arched ceilings. Each arch has stripes that are painted radially across them.

Others made notable contributions to science and mathematics. Al-Khwarizmi (c. 780–850 CE) modified Indian digits into Arabic numerals and wrote the first book on algebra. The renowned Abbasid philosopher al-Farabi (d. 950 CE), from a Perso-Turkish military family, also made his way to Baghdad, where he studied classical thought, music, and the sciences. He was the first Muslim neo-Platonist, believing that good societies would succeed only if their rulers implemented the political tenets espoused in Plato’s Republic. He championed the idea of a virtuous “first chief” to rule over an Islamic commonwealth in the same way that Plato had favored a philosopher-king.

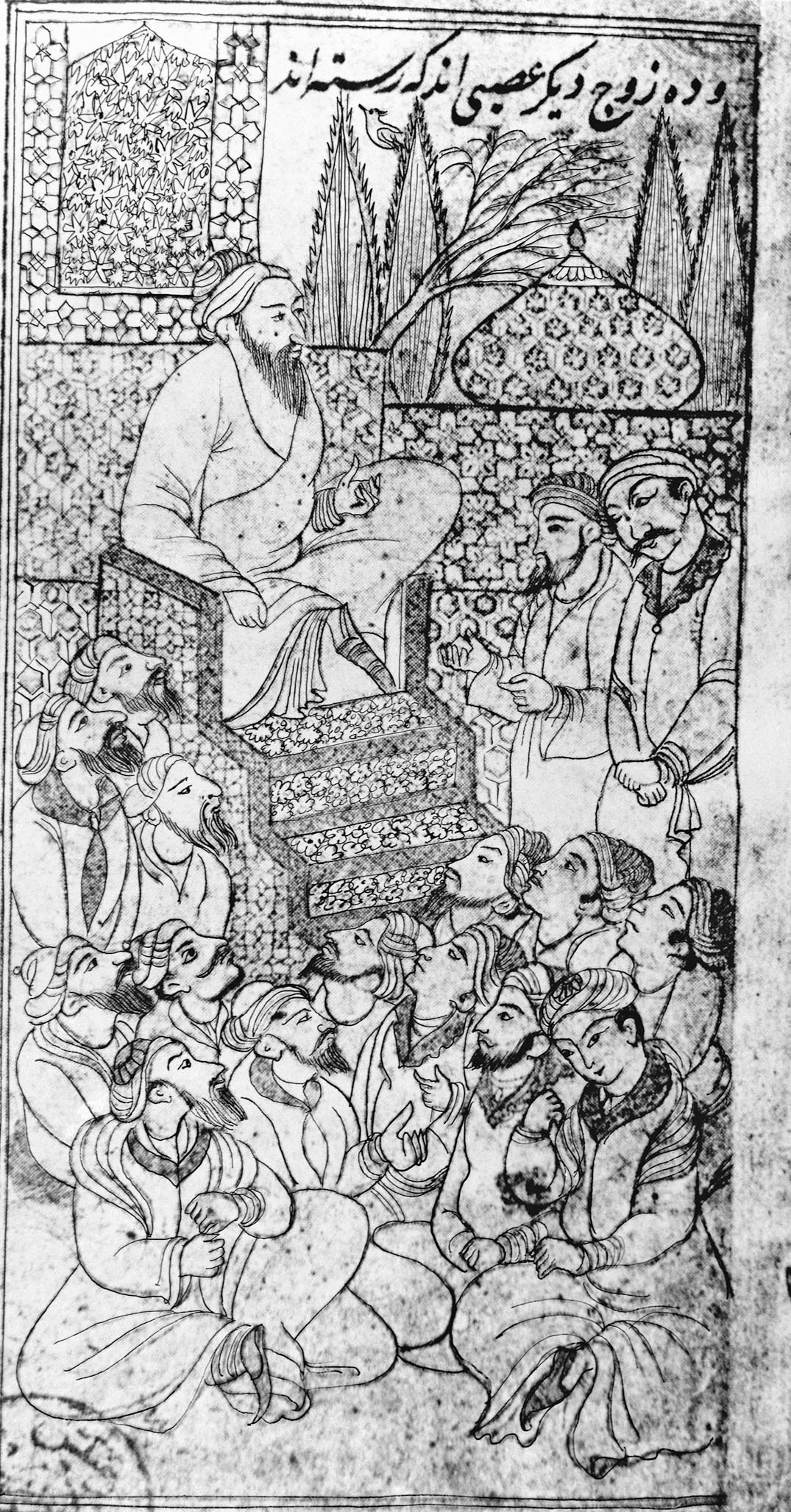

In the eleventh century, the Abbasid caliphate began to decline, devastated by climatic change (see Chapter 10) and weakened from overextension and the influx of outsider groups (the same problems the Roman Empire had faced). Scholars no longer trekked to the court at Baghdad. Yet intellectual vitality remained strong in the broader Abbasid realm, as young men of learning found patrons among local rulers. Consider Ibn Sina, known in the west as Avicenna (980–1037 CE). He grew to adulthood in Bukhara, practiced medicine in the courts of various Muslim rulers, and spent his later life in central Persia. Schooled in the Quran, Arabic literature, philosophy, geometry, and Indian and Euclidean mathematics, Ibn Sina was a master of many disciplines. His Canon of Medicine stood as the standard medical text in both Southwest Asia and Europe for centuries.

More information

A black-and-white illustration shows Ibn Sina sitting whilst a group of men listen to him. Ibn Sina sits on a chair at the top of several steps and the group of men sit on the floor below looking up at him. Several men stand to the side of the chair. The chair and the wall behind it are intricately patterned. There is a window with a view of a dome and several trees in the background. Some script is at the top of the illustration.

More information

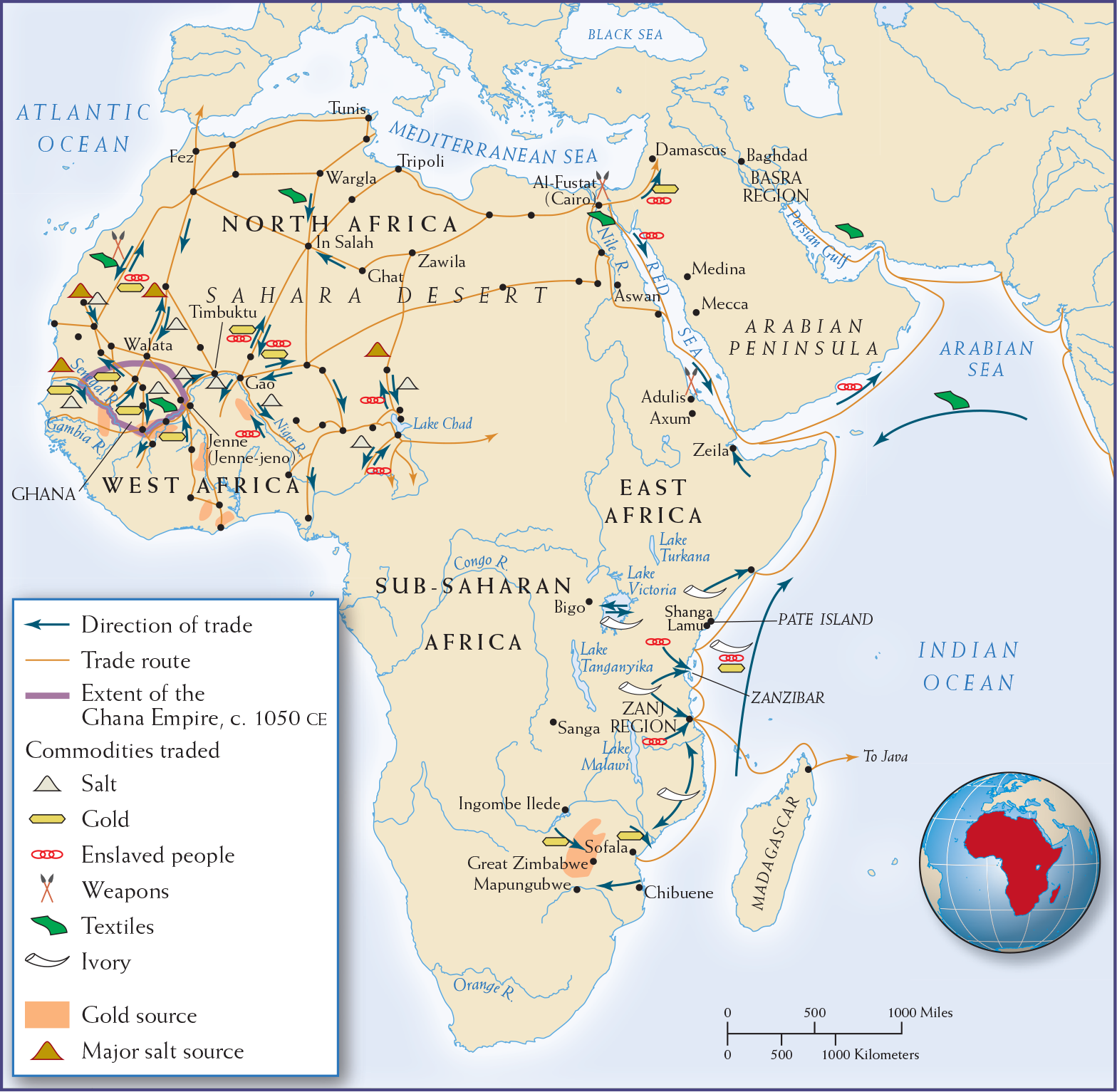

Map 9.3 is titled Islam and Trade in Sub-Saharan Africa, 700-1000 C E. The map shows the extent of the Ghana Empire circa 1050 C E (a circular area around the Senegal River in West Africa), as well as the direction of trade along trade routes, commodities trading, and gold and major salt sources. Trade routes span across northern Africa and on the eastern coast from Madagascar up to the Arabian Peninsula. Most of the trade routes are in the upper North Western portions of Africa, centered on the Ghana Empire. Different commodities such as salt, gold, slaves, weapons, textiles, and ivory are marked on the map. Ivory is concentrated in and around the Zanj Region of East Africa, with gold and slaves in nearby areas and also across West Africa, where weapons, salt, and textiles are concentrated as well. Gold sources are found in southern Africa near Great Zimbabwe, and West Africa. Major salt sources are found in and around the Sahara Desert, as well as along the coast of West Africa.

MAP 9.3 | Islam and Trade in Sub-Saharan Africa, 700–1000 CE

Muslim merchants and scholars, not armies, carried Islam into sub-Saharan Africa. Trace the trade routes in Africa, making sure to follow the correct direction of trade.

- According to the map key and icons, what commodities were Muslim merchants seeking south of the Sahara?

- What were the major trade routes and the direction of trade in Africa?

- How did trade and commerce shape the geographic expansion of the Islamic faith?

TRADE AND ISLAM IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA Carried by traders and scholars on sand routes, Islam crossed the Sahara Desert from North Africa and penetrated well into the interior (see Map 9.3); in West Africa, Muslim merchants exchanged weapons and textiles for gold, salt, and enslaved people. Trade did more than join West Africa to North Africa. It also generated prodigious wealth, which allowed centralized political kingdoms to develop. The most celebrated was Ghana, which lay at the terminus of North Africa’s major trading routes.

Seafaring Muslim traders carried Islam into East Africa via the Indian Ocean. There is evidence of a small eighth-century CE Muslim trading community at Lamu, along the northern coast of present-day Kenya; and by the mid-ninth century CE, other coastal trading communities had sprung up. They all exported ivory and, possibly, enslaved people. On the island of Pate, off the coast of Kenya, the inhabitants of Shanga constructed the region’s first mosque. This simple structure was replaced 200 years later by a mosque capable of holding all adult members of the community when they gathered for Friday prayers. By the tenth century CE, the East African coast featured a mixed African-Arab culture. The region’s evolving Bantu language absorbed Arabic words and before long gained a new name, Swahili (derived from the Arabic plural of the word meaning “coast”). In sub-Saharan Africa, as in North Africa and Asia, Islam promoted trade and elevated the status of merchants, who were themselves important agents for spreading their faith.

GREEN REVOLUTION IN THE ISLAMIC WORLD New crops, especially food crops, leaped across political and cultural borders during this period, offering expanding populations more diverse and nutritious diets and the ability to feed increased numbers. Most of these crops originated in Southeast Asia, made their way to India, and were dispersed throughout the Muslim world and into China. They included new strains of rice, taro, sour oranges, lemons, limes, and most likely coconut palm trees, sugarcane, bananas, plantains, and mangoes. Sorghum and possibly cotton and watermelons were exported from Africa.

Once Muslims conquered the Sindh in northern India in 711 CE, the crop innovations pioneered in Southeast Asia made their way westward. Soon a “green revolution” in crops and diet swept through the Muslim world. Sorghum supplanted millet and the other grains of antiquity because it was hardier, had higher yields, and required a shorter growing season. Citrus trees added flavor to the diet and provided refreshing drinks during the summer heat. Increased cotton cultivation led to a greater demand for textiles.

More information

The mosque has three studded towers with about twenty smaller spiked wall sections in between and steps leading to the central tower.

Farmers from northwest India to Spain, Morocco, and West Africa made impressive use of the new crops. They increased agricultural output, slashed the duration of fallow periods, and grew as many as three crops on lands that formerly had yielded just one. (See Map 9.4.) As a result, farmers could feed larger communities; even as cities grew, the countryside became more densely populated and even more productive.

Glossary

- five pillars of Islam

- Five practices that unite all Muslims: (1) proclaiming that “there is no God but God and Muhammad is His Prophet”; (2) praying five times a day; (3) fasting during the daylight hours of the holy month of Ramadan; (4) traveling on pilgrimage to Mecca; and (5) paying alms to support the poor.

- Sunnis

- Majority sect within modern Islam that follows a line of political succession from Muhammad, through the first four caliphs (Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali), to the Umayyads and beyond, with caliphs chosen by election from the umma (not from Muhammad’s direct lineage).

- Shiites

- Minority tradition within modern Islam that traces political succession through the lineage of Muhammad and breaks with Sunni understandings of succession at the death of Ali (cousin and son-in-law of Muhammad and fourth caliph) in 661 CE.

- caliphate

- Islamic state, headed by a caliph—chosen either by election from the community (Sunni) or from the lineage of Muhammad (Shiite)—with political authority over the Muslim community.

- sharia