10Becoming “The World”

1000–1300 CE

More information

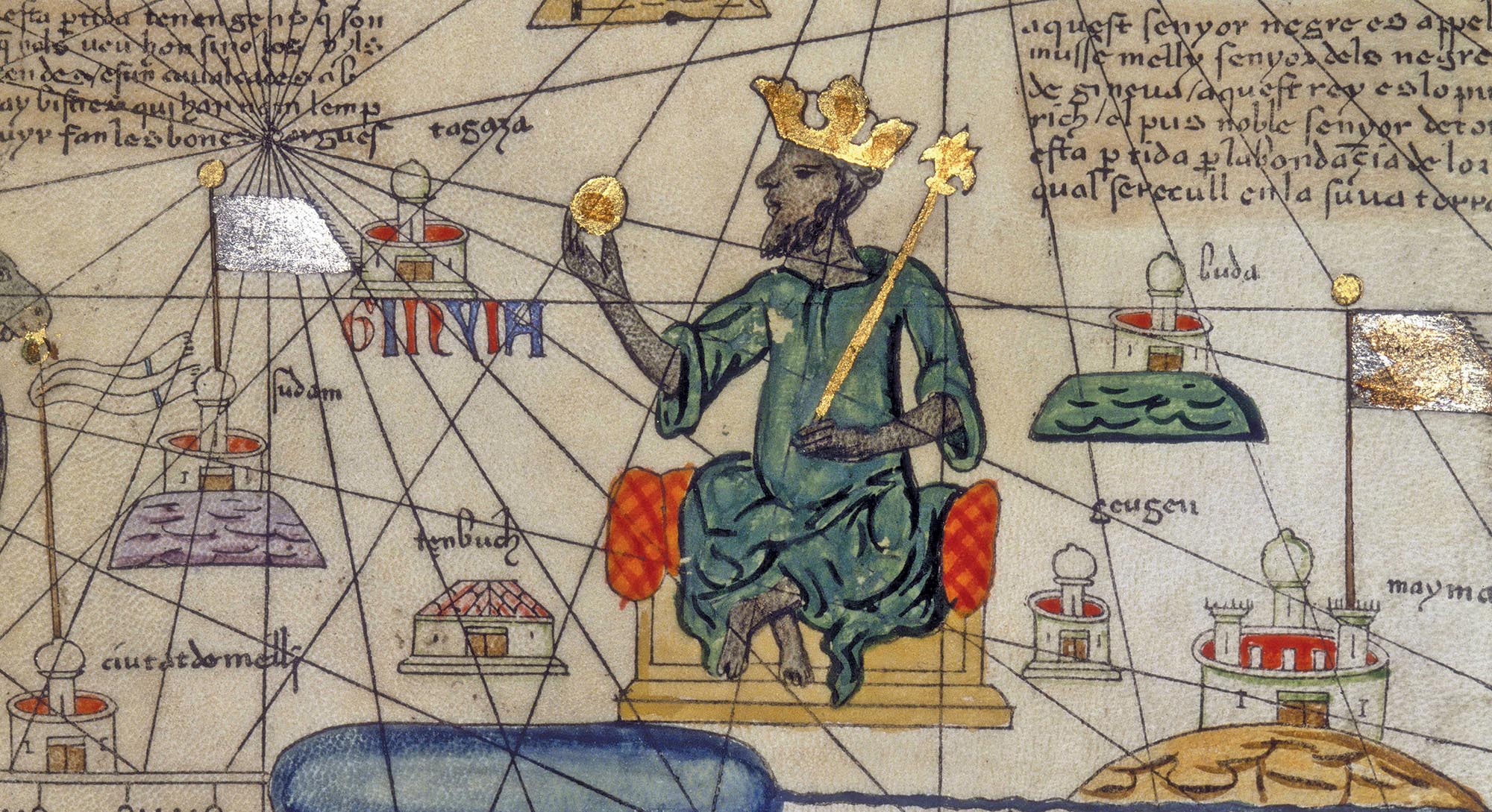

A painting of the King of Mali. The king sits on a throne, wears a crown, and holds up a golden staff and a golden ball. The painting of the king is placed on top of a map of Mali with small illustrations of buildings denoting different locations. There is script scattered throughout the painting and in a large block at the top right corner.

Before You Read This Chapter

GLOBAL STORYLINES

The Emergence of the World We Know Today

- Advances in maritime technology lead to increased sea trade, thereby transforming coastal cities into global trading hubs and deepening the connections across Afro-Eurasia.

- Intensified contact through trade and religion help consolidate four major cultural “spheres”: the Islamic world, India, China, and Christian Europe.

- Sub-Saharan African states are integrated into Eurasian exchange networks, resulting in a true Afro-Eurasia-wide network; over the same time period, some states and societies in the Americas experience limited political, economic, and cultural integration.

- The Mongol Empire helps integrate many of Afro-Eurasia’s major cultural spheres.

CHAPTER OUTLINE

FOCUS QUESTIONS

- What technological advances occurred during this period, especially in ship design and navigation, and how did they facilitate the expansion of Afro-Eurasian trade?

- What social and political forces shaped the Islamic world, India, China, and Christian Europe at this time? To what degree did these forces integrate cultural and geographical areas?

- How did sub-Saharan Africa and the Americas compare with each other, and with the connected Eurasian world, in terms of external interactions and internal consolidation and integration?

- In what ways did the Mongol Empire influence peoples and places across Afro-Eurasia?

Two Nestorian Christian monks, Bar Sāwmā and Markōs, voyaged in the late 1270s from the court of the Mongol leader Kublai Khan in what is now Beijing westward into the heart of the Islamic world and beyond. The monks were not Europeans; rather, they were Uighurs, a Turkish people of central Asia, many of whom had converted centuries earlier to Christianity. The monks hoped to make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem to visit the tombs of martyrs enshrined there and along the way. On their journey, Bar Sāwmā and Markōs traversed a world that had been bound together through economic and cultural exchange. The two monks lingered at the magnificent trading hub of Kashgar in what is now western China, where caravan routes converged at a market for jade, exotic spices, and precious silks. The monks parted ways at Baghdad, unable to continue on to Jerusalem, a result of the route’s dangers (including murderous robbers). (See Global Themes and Sources: Primary Source 10.1.) Later, in 1287, Bar Sāwmā was appointed ambassador by the Buddhist Mongol il-Khan of Persia, Arghūn. Bar Sāwmā was assigned to drum up support among European leaders for an attack on Jerusalem, in order to wrest it from Muslim control. He visited Constantinople (where the Byzantine emperor gave him gold and silver), Rome (where he met with the pope at the shrine of Saint Peter), Paris (where he saw that city’s vibrant university), and Bordeaux (where he was welcomed by the English king, Edward I). In the end, neither monk reached Jerusalem nor did they return to China. Bar Sāwmā ended his days in Baghdad, and Markōs became patriarch of the Nestorian branch of Christianity, centered in modern-day Iran. Yet their voyages exemplified the crisscrossing of people, money, goods, and ideas along the trade routes and sea-lanes that increasingly connected the continents of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Collectively known as Afro-Eurasia, places across the region experienced increased interaction after about 1000 CE. As a result of these interactions, disparate locations became to a degree parts of a single entity, which connected locations across the globe’s Eastern Hemisphere.

Three related themes dominate the period from 1000 to 1300 CE, at the end of which a monk like Bar Sāwmā could make such a lengthy journey. First, increased trade along sea-based routes caused the dramatic expansion of coastal trading cities. Second, greater trade and religious interaction generated the Afro-Eurasian world’s four major cultural “spheres”: the Islamic world, India, China, and Christian Europe. The inhabitants within each sphere were connected through shared institutions and beliefs. Societies and states in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Americas also thrived during this period; they remained more fragmented, however, experiencing more limited political and economic integration than in Afro-Eurasia. Third, the Mongol Empire, stretching from China to Persia and even as far as eastern Europe, ruled over huge swaths of land in the world’s major cultural spheres. Each of these three themes contributes to an understanding of how places in Afro-Eurasia connected themselves through migration, trade, and religion (including religious conflict) in order to became a “world.”