Conclusion

Between 1000 and 1300 CE, Afro-Eurasia formed four large cultural spheres. As trade and migration spanned longer distances, each of these spheres expanded, prospered, and became more integrated. In central Afro-Eurasia, Islam was firmly established, and its merchants, scholars, and travelers acted as commercial and cultural intermediaries as they exposed others to their universalizing religion. As seaborne trade expanded, India, too, became a commercial crossroads. Merchants in its port cities welcomed traders arriving from Arab lands to the west, from China to the east, and from Southeast Asia. China itself also boomed, pouring its manufactures into trading networks that reached across Eurasia and North Africa and even into sub-Saharan Africa. Christian Europe had two religious centers at Rome and Constantinople; states supporting each found ways to challenge polities that had adopted Islam as the primary religion. Each of these spheres consolidated internally while also engaging the other spheres through commerce, religion, and even conquest.

Neither the Americas nor sub-Saharan Africa experienced the same degree of integration, but trade and migration in these areas nevertheless had profound effects. Certain African cultures flourished as they encountered the commercial energy of trade on the Indian Ocean. Africans’ trade with one another linked coastal and interior regions in an ever more integrated world. American peoples built cities that dominated regional cultural areas and that were also connected through trade of foodstuffs (such as maize), cotton, or even luxury goods.

By 1300, trade, migration, and conflict connected Afro-Eurasian worlds in unprecedented ways. When Mongol armies swept into China, Southeast Asia, and the heart of Islamic territories to the west, they applied a thin coating of political integration to these far-flung regions and built on existing trade links. It is important to note that, at the same time, most people remained focused on local life, driven by the need for subsistence and governed by spiritual and governmental representatives acting at the behest of distant authorities.

Even so, residents noticed the evidence of cross-cultural exchanges everywhere—in the clothing styles of provincial elites, such as Chinese silks in Paris or quetzal plumes in northern Mexico; in enticements to move (and forced removals) to new frontiers; in the news of faraway conquests or advancing armies. Worlds were coming together within themselves and across territorial boundaries, while nevertheless remaining apart as they sought, or struggled, to maintain their own identity and traditions. In Afro-Eurasia especially, as the movement of goods and peoples shifted from ancient land routes to sea-lanes, these contacts were more frequent and far-reaching. Never before had the world seen so much activity connecting its parts to each other. And within each of these spheres, never before had there been so much shared cultural similarity—linguistic, religious, legal, and military. By the time the Mongol Empire arose, the regions composing the globe were well on the way to becoming those that we now recognize as today’s cultural spheres.

After You Read This Chapter

Go to  to see what you’ve learned—and learn what you’ve missed—with personalized feedback along the way.

to see what you’ve learned—and learn what you’ve missed—with personalized feedback along the way.

TRACING THE GLOBAL STORYLINE

FOCUS ON: The Emergence of the World We Know Today

The Islamic World

- The Islamic world undergoes a burst of expansion, prosperity, and cultural diversification but remains politically fractured.

- Arab merchants and Sufi mystics spread Islam over great distances and make it more appealing to other cultures, helping to transform the religion into the unifying force of a distinct cultural sphere.

- Islam travels across the Sahara Desert; the powerful empire of Mali, supplying gold and enslaved people, arises in West Africa.

China

- The Song dynasty reunites China after three centuries of fragmented rulership, reaching into the past to reestablish a sense of a “true” Han Chinese identity, through a widespread print culture and the denigration of outsiders.

- Agrarian success and advances in manufacturing—including the production of both iron and porcelain—fuel an expanding economy, complete with paper money.

India

- India remains a mosaic under the canopy of Hinduism despite cultural interconnections and increasing prosperity.

- The invasion of Turkish Muslims leads to the creation of the Delhi Sultanate, which rules over India for three centuries, strengthening both cultural diversity and tolerance.

Christian Europe

- Roman Catholicism becomes a “mass” faith and helps create a common European cultural identity, at least in western Europe. A second center continues in Constantinople, providing a focal point for Eastern Orthodox Christianity, which spreads to the north.

- Feudalism organizes the relationship between elites and peasants, while manorialism forms the basis of the economy.

- Europe’s growing confidence is manifest in its efforts, including the Crusades and the reconquering of Iberia, to drive Islam out of “Christian” lands.

KEY TERMS

THINKING ABOUT GLOBAL CONNECTIONS

- Thinking about Worlds Together, Worlds Apart From 1000 to 1300 CE, a range of social and political developments contributed to the consolidation of four cultural spheres that still exist today: Europe, the Islamic world, India, and China. In what ways did these spheres interact with one another? In what ways was each sphere genuinely distinct from the others? To what extent were sub-Saharan Africa and the Americas folded into these spheres, and with what result?

- Thinking about Transformation & Conflict and Becoming the World As the four cultural spheres of Afro-Eurasia consolidated, shocking examples of conflict between them began to take place. Whether from Pope Urban II’s call in 1095 to reclaim the “holy land” from Muslims or the Mongol Hulagu’s brutal sack of Baghdad in 1258, this period was marked by large-scale warfare between rival cultural spheres. To what extent was such conflict inevitable? In what ways did conflict transform the groups involved?

- Thinking about Crossing Borders and Becoming the World Major innovations facilitated economic exchange in the Indian Ocean and in Song China. The magnetic needle compass, better ships, and improved maps shrank the Indian Ocean to the benefit of traders. Similarly, paper money in Song China changed the nature of commerce. How did these developments shift the axis of Afro-Eurasian exchange? What evidence suggests that bodies of water and the routes across them became more significant than overland exchange routes in binding together Afro-Eurasia? What were the longer-term implications of these developments?

CHRONOLOGY

More information

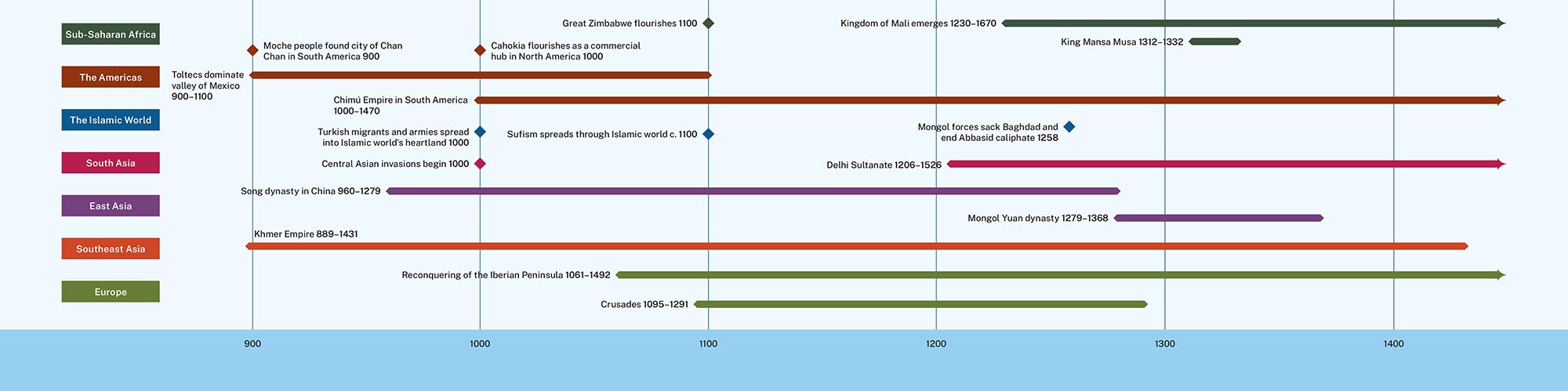

A timeline showing events from circa 900 to 1400. The timeline shows various events represented by diamonds and lines color coded by region of the world that are situated between and around lines representing 900, 1000, 1100, 1200, 1300 and 1400. In Sub-Saharan Africa, Great Zimbabwe flourishes in 1100, Kingdom of Mali emerges in 1230 to 1670, and King Mansa Musa is placed in 1312 to 1332. In the Americas, the Toltecs dominate the valley of Mexico in 900 to 1100 and the Chimú Empire in South America is placed at 1000 to 1470. In the Islamic world, Turkish migrants and armies spread Turkish migrants and armies spread into Islamic world’s heartland circa 1000, Sufism spreads through Islamic world circa 1100, and Mongol forces sack Baghdad and end Abbasid caliphate circa 1258. In South Asia, Central Asian invasions begin circa 1000 and the Delhi Sultanate was placed at 1206 to 1526. In East Asia, Song dynasty in China is placed at 960 to 1279 and Mongol Yuan dynasty is placed at 1279–1368. In Southeast Asia, the Khmer Empire is placed at 889 to 1431. In Europe, the reconquering of the Iberian Peninsula is placed at 1061 to 1492 and the crusades are placed at 1095 to 1291.

Glossary

- Cahokia

- Commercial city on the Mississippi for regional and long-distance trade of commodities such as salt, shells, and skins and of manufactured goods such as pottery, textiles, and jewelry; marked by massive artificial hills, akin to earthen pyramids, used to honor spiritual forces.

- Chimú Empire

- South America’s first empire, centered at Chan Chan, in the Moche Valley on the Pacific coast from 1000 through 1470 CE, whose development was fueled by agriculture and commercial exchange.

- Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526)

- A Turkish Muslim regime in northern India that, through its tolerance for cultural diversity, brought political integration without enforcing cultural homogeneity.

- entrepôts

- Multiethnic trading stations, often supported and protected by regional leaders, where traders exchanged commodities and replenished supplies in order to facilitate long-distance trade.

- flying cash

- Letters of exchange—early predecessors of paper money—first developed by guilds in the northern Song province Shanxi that eclipsed coins by the thirteenth century.

- jizya

- Special tax that non-Muslims were forced to pay to their Islamic rulers in return for which they were given security and property and granted cultural autonomy.

- Mali Empire

- West African empire, founded by the legendary king Sundiata in the early thirteenth century. It facilitated thriving commerce along routes linking the Atlantic Ocean, the Sahara, and beyond.

- manorialism

- System in which the manor (a lord’s home, its associated industry, and surrounding fields) served as the basic unit of economic power; an alternative to the concept of feudalism (the hierarchical relationships of king, lords, and peasantry) for thinking about the nature of power in western Europe from 1000 to 1300 CE.

- Sufism

- Emotional and mystical form of Islam that appealed to the common people.

- Toltecs

- Mesoamerican peoples who filled the political vacuum left by Teotihuacán’s decline; established a temple-filled capital and commercial hub at Tula.