NAWM 14aAnonymous, Organa from Musica enchiriadis, Tu patris sempiternus es filius

Early Organum

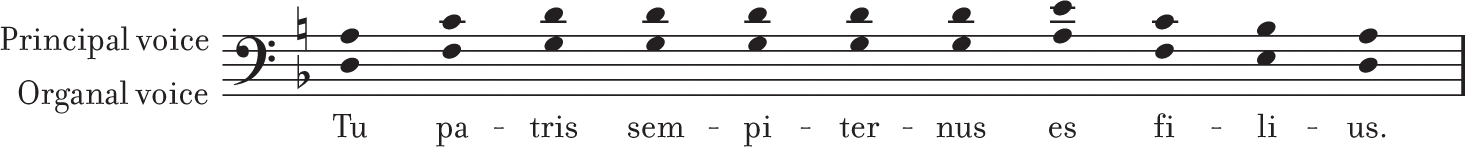

The anonymous ninth-century author of Musica enchiriadis examines and illustrates two distinct kinds of singing together, both designated by the term organum. In one species of this early organum, a plainchant melody in the principal voice (Latin, vox principalis) is duplicated a fourth or fifth below by an organal voice (Latin, vox organalis). Example 3.1 shows parallel organum at the fifth below (NAWM 14a). Either voice or both may be further duplicated at the octave to create an even richer sound (NAWM 14b). Of course, singing in parallel fourths or fifths sometimes produces a harsh tritone (such as occurs between F and B), and the adjustments needed to avoid it led to organum that was not strictly parallel (Example 3.2 and NAWM 14c). In this type, called oblique organum or organum with oblique motion, the added part was melodically different from the plainchant, and a wider variety of intervals, including dissonances, were sounded.

NAWM 14bAnonymous, Organa from Musica enchiriadis, Sit gloria domini

NAWM 14cAnonymous, Organa from Musica enchiriadis, Rex caeli domine

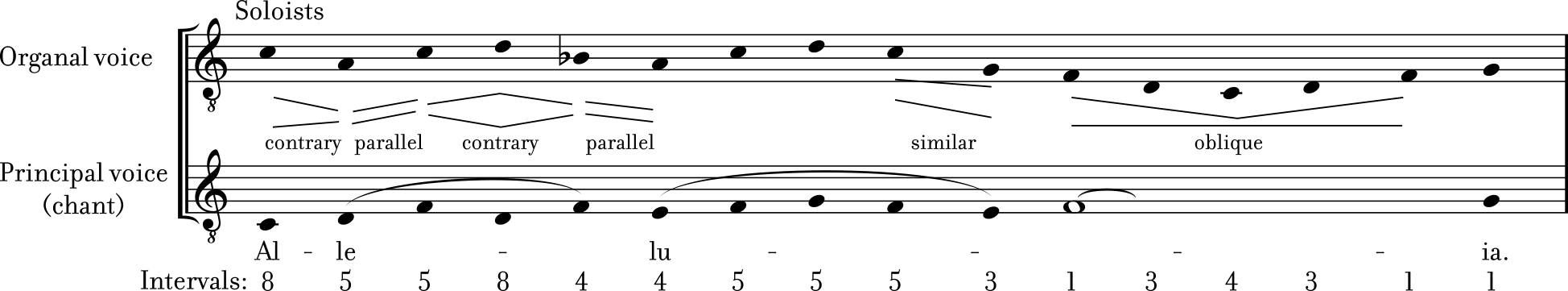

In eleventh-century music, contrary and oblique motion predominated over parallel motion, and, as a consequence, the polyphonic voices grew increasingly independent and more like equal partners. Though the parts often cross, the organal voice shifted to a position above the chant, where it gained more rhythmic and melodic prominence, occasionally singing two notes against one of the principal voice. Consonant intervals — the unison, octave, fourth, and fifth — prevail, while others — including thirds, then understood as dissonant —occur only incidentally (Example 3.3). The rhythm is identical to the unmeasured flow of plainchant, which forms the basis for all these pieces.

Example 3.1 Parallel organum at the fifth below, from Musica enchiriadis

More information

You of the Father are the everlasting Son.

Example 3.2 Mixed parallel and oblique organum, from Musica enchiriadis

More information

King of Heaven, Lord of the roaring sea.

Example 3.3 Free organum, from Ad organum faciendum

More information

In the eleventh century, polyphony was applied chiefly to the troped plainchant sections of the Mass Ordinary (such as the Kyrie and Gloria), to certain parts of the Proper (Tracts and Sequences), and to responsories of the Office and Mass (Graduals and Alleluias). Because polyphony demanded trained soloists who could follow rules of consonance while improvising or who could read the approximate notation, only the soloists’ portions of the original chant were embellished polyphonically. In performance, then, polyphonic sections alternated with monophonic chant, which the full choir sang in unison. The solo sections from the Alleluia Justus ut palma (NAWM 15) are preserved in a set of instructions headed Ad organum faciendum (On making organum) and date from about 1100. The added voice proceeds mostly note against note above the chant, but toward the end of the opening “Alleluia” the performer sings a melismatic passage against a single note of the chant (Example 3.3). In this new style of organum, known today as free organum, the organal voice has more rhythmic and melodic independence.

NAWM 15Anonymous, Alleluia Justus ut palma, from Ad organum faciendum

(Bridgeman-Giraudon/Art Resource, NY.)

A more florid style of free organum appeared early in the twelfth century in Aquitaine, a region in southwestern France. In Aquitanian organum, the lower voice, usually an existing chant but sometimes an original melody, sustains long notes while the upper (solo) voice sings decorative phrases of varying length. Pieces in this new style resulted in much longer organa, with a more prominent upper part that moved independently of the lower one. The chant meanwhile became elongated into a series of single-note “drones” that supported the melismatic elaborations above, thereby completely losing its character as a recognizable tune. The lower voice was called the tenor, from the Latin tenere (“to hold”), because it held the principal — that is, the first or original — melody. For the next 250 years, the word tenor designated the lowest part of a polyphonic composition.

Writers in the early twelfth century began distinguishing between two kinds of organum. For the style just described, in which the lower voice sustains long notes while the upper voice moves more melismatically, they reserved the terms organum, organum duplum, or organum purum (“double organum” and “pure organum,” respectively), all of which we now associate with organum that is free or florid in style. The other kind, in which the movement is primarily note against note, they called discantus (discant). When the Notre Dame composer Leoninus was praised by a contemporary writer as optimus organista, he was not being called an excellent organist but the best singer or composer of organum (see Biography, p. 59). The same writer described Perotinus, Leoninus’s younger colleague, as the best discantor, or maker of discants. In both styles, the upper part elaborates an underlying note-against-note counterpoint with the tenor.

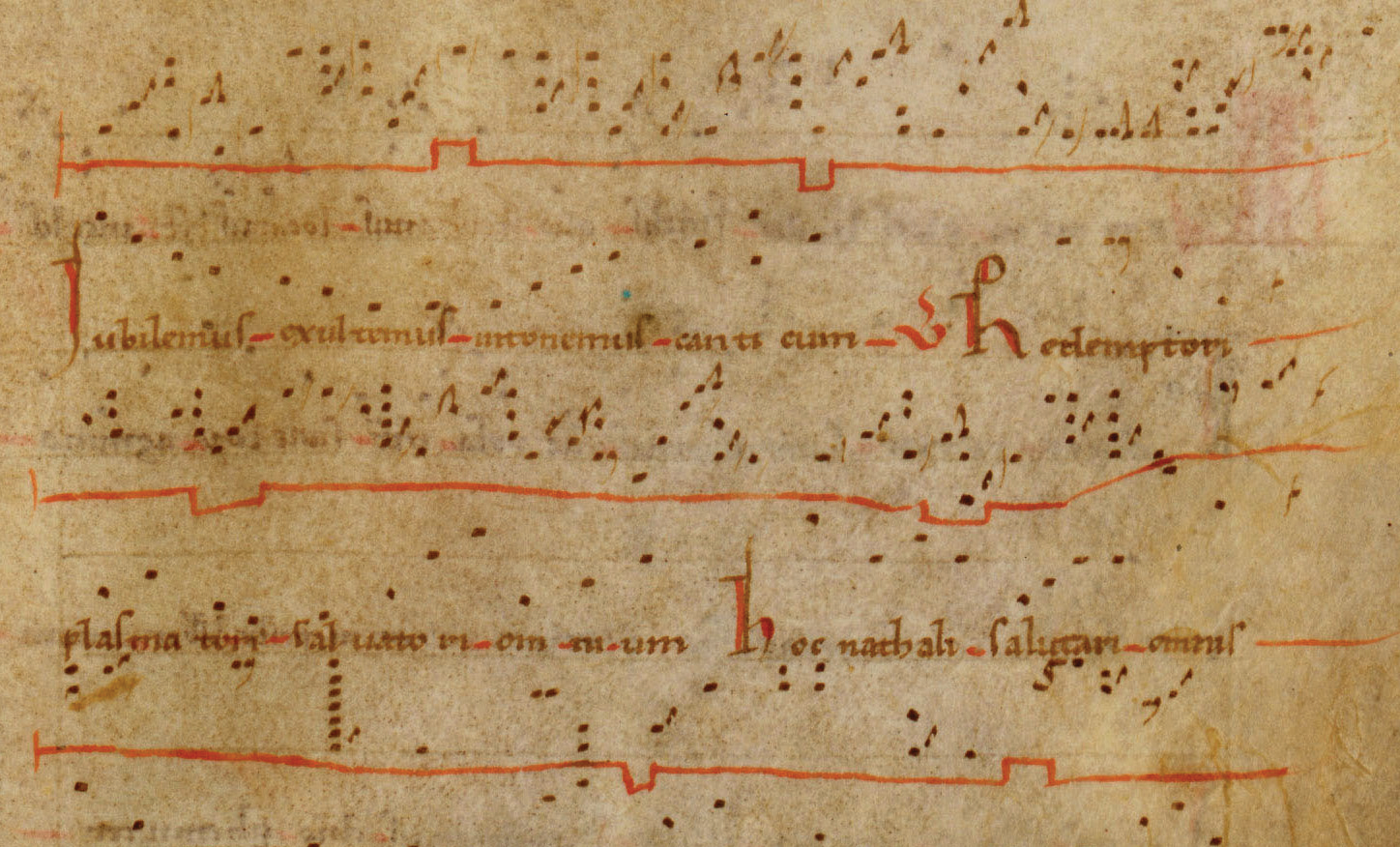

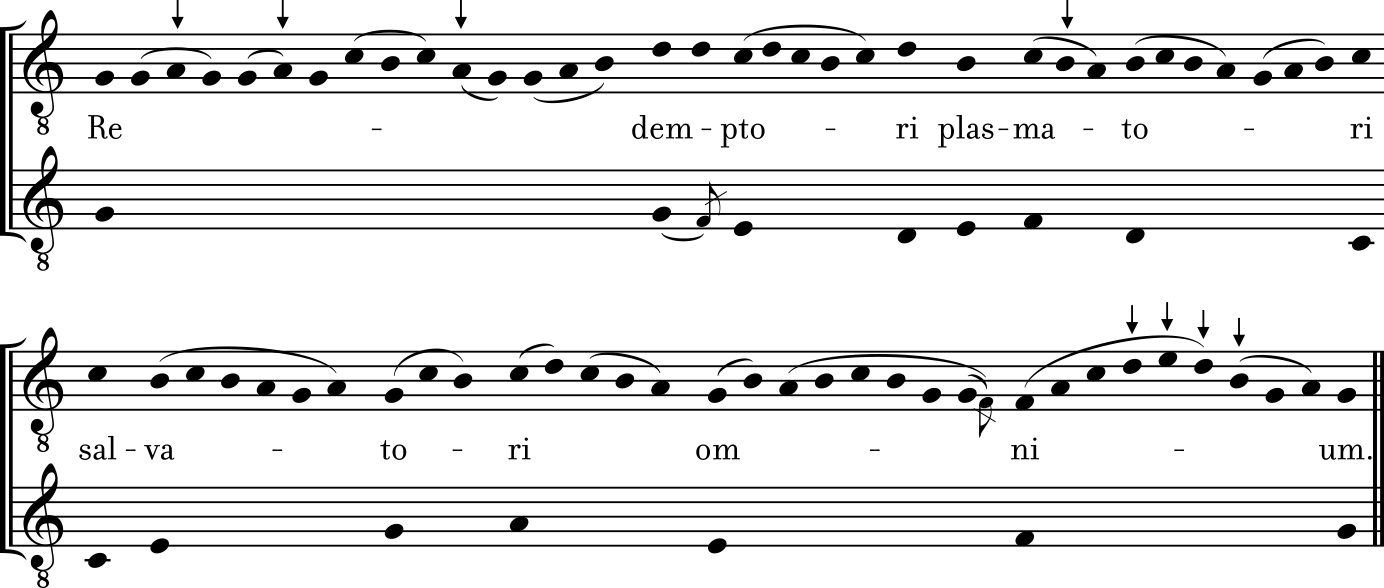

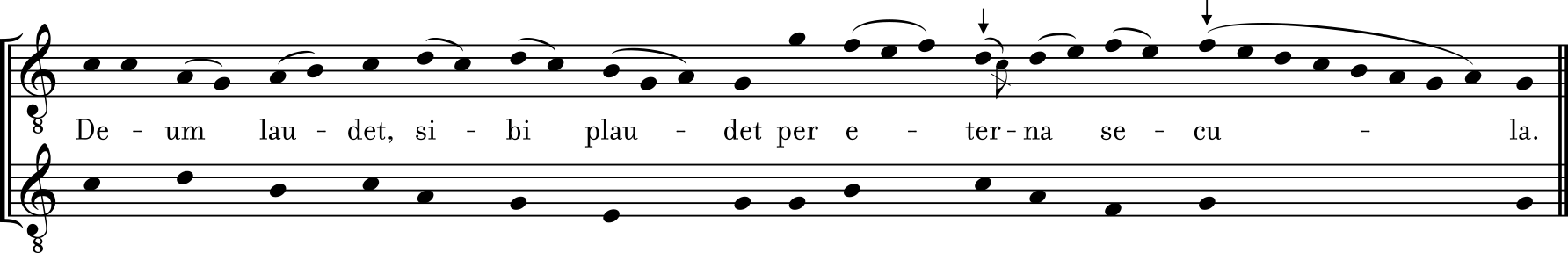

We can see a good example of florid Aquitanian organum and discant in the two-voice Jubilemus, exultemus, illustrated in Figure 3.3 and transcribed in Example 3.4 (see NAWM 16 for the complete version and Figure 3.2). The section in Example 3.4a uses the florid style of organum, with melismas of three to fifteen notes in the upper part for most notes in the tenor. Example 3.4b shows a passage in discant style, with fewer notes in the upper part for every tenor note until the penultimate syllable, which typically has a longer melisma. In both excerpts, contrary motion is more common than parallel, and most note groups in the upper voice begin on a perfect consonance with the tenor, although dissonances generously pepper the melismas. In the discant section, the composer seems to have chosen an occasional dissonance above the tenor note for variety and spice (as in “-ter-” of “eterna” and “-cu-” of “secula,” shown by the arrows). Phrases end on octaves or unisons, emphasizing closure.

NAWM 16Anonymous, Jubilemus, exultemus

When organum was written down (ordinarily it was not), one part sat above the other, fairly well aligned as in a modern score, with the phrases marked off by short vertical strokes on the staff. Two singers, or one soloist and a small group, could not easily go astray. But when the rhythmic relation between the parts became complex, singers had to know exactly how long to hold each note. As we have seen, the late medieval notations of plainchant and of troubadour and trouvère songs did not indicate duration. Indeed, no one felt a need to specify it, for the rhythm was either free or was communicated orally. Uncertainty about note duration was not a serious concern in solo or monophonic singing but could cause chaos when two or more melodies were sung simultaneously. Singers in northern France solved this problem by devising a system of rhythmic notation involving patterns of long and short notes known today as the rhythmic modes (see Innovations, p. 56).

More information

(Photograph Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, fonds Latin, MS 1139, fol. 41.)

Example 3.4 Aquitanian (florid) organum and discant in Jubilemus, exultemus

a. Verse 2

More information

To the redeemer, creator, savior of all.

b. Verse 4

More information

Praise God and eternally applaud.