NAWM 17Leoninus and colleagues, Viderunt omnes

Notre Dame Polyphony

Musicians in Paris developed a still more ornate style of polyphony in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. Two musicians associated with the new Cathedral of Notre Dame (“Our Lady,” the Virgin Mary; see Figure 3.4) were Leoninus (fl. 1150s–ca. 1201), who was a priest and poet-musician, and Perotinus (fl. 1200–1230), who probably trained as a singer under Leoninus (see Biography, p. 59). Both may have studied at the University of Paris, which was becoming a center of intellectual innovation; a typical classroom setting is shown in Figure 3.9. Leoninus was credited with having compiled a Magnus liber organi (“great book of polyphony”). This collection contained two-voice settings of the solo portions of the responsorial chants (Graduals and Alleluias of the Mass, and Office responsories) for the major feasts of the church year, some or all of which he himself composed. To undertake such a cycle shows a vision as grand as that of the builders of Notre Dame Cathedral. The Magnus liber offers different settings for the same passages of chant, including organa for two, three, and four voices, making them ideal for tracing the process of revision and substitution by which the repertory grew and the style evolved from one generation to the next. An ideal example is Viderunt omnes, the Gradual for Christmas Day.

More information

(Laurent Lucuix/Alamy Stock Photo.)

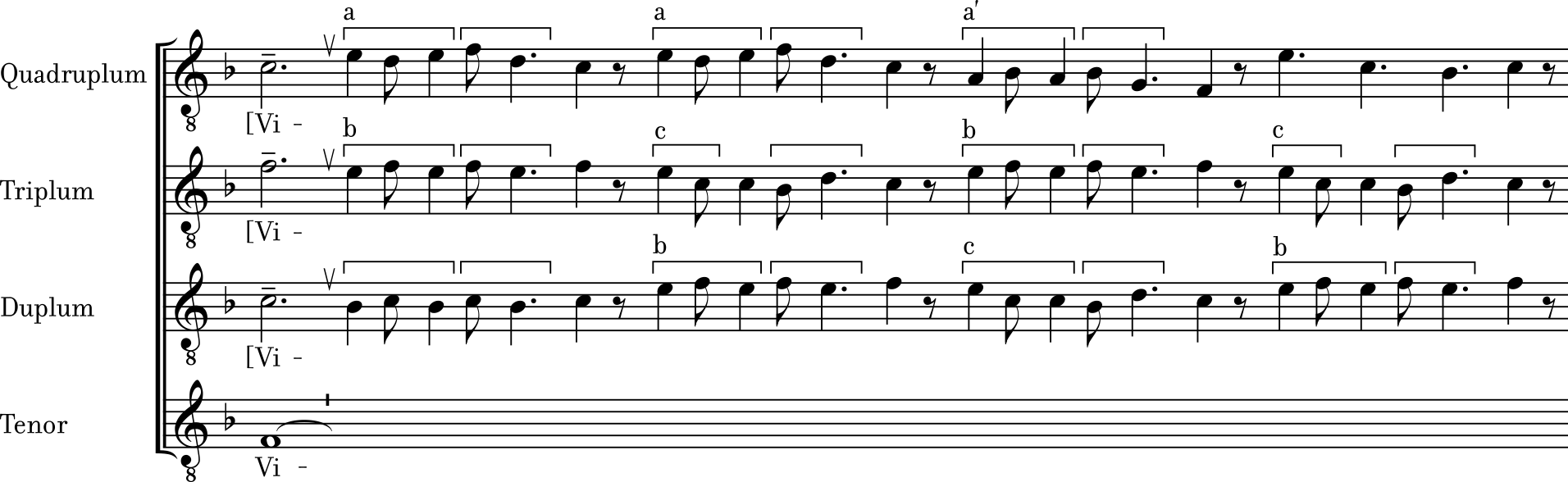

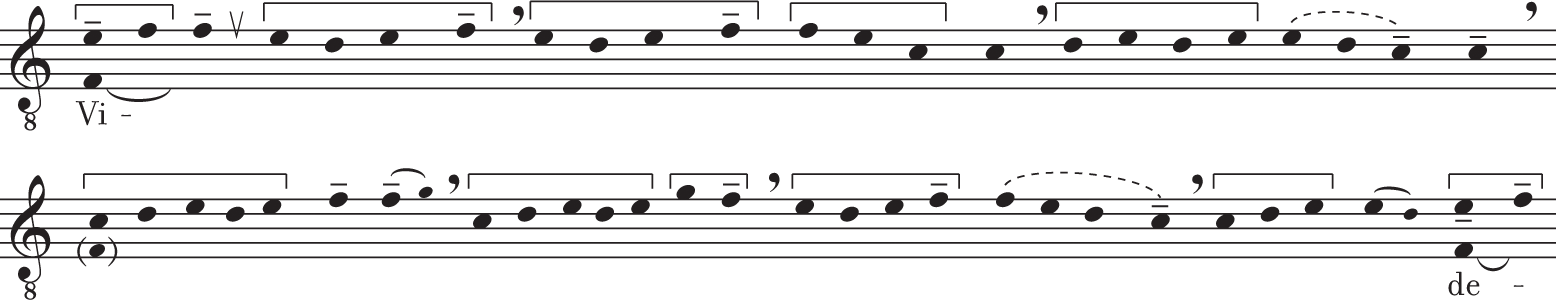

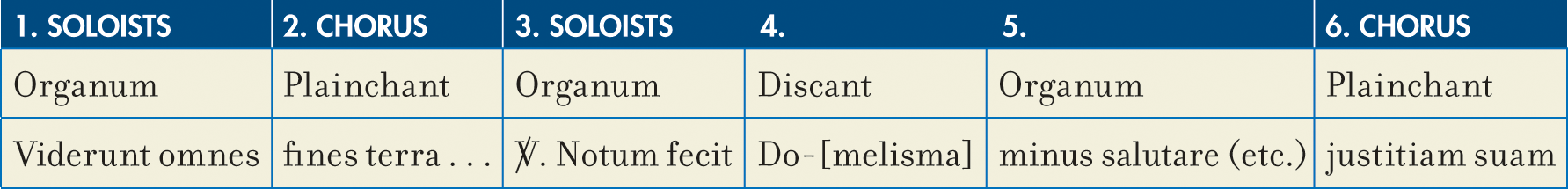

If we compare the setting ascribed to Leoninus and colleagues of Viderunt omnes (NAWM 17) to the original chant (NAWM 3d), we see that polyphonic music is provided only for the sections of the chant performed by soloists, while the choir was expected to sing the rest of the melody in unison (see Figure 2.11). The responsorial chant by itself displays contrasts in form and sound in that some sections are syllabic and others are melismatic. The elaboration emphasizes these contrasts by featuring two different styles of polyphony, organum and discant (see Figure 3.5). In the opening section on “Viderunt,” shown in Example 3.5, the organum extends the notes of the original melody into a series of drones, while the added voice spins expansive melismas above it. The original notation suggests a free, unmeasured rhythm; the fluid melody — loosely organized in a succession of unequal phrases often lingering on dissonances with the tenor — suggests improvisational practice. Then, as the choir enters after the word “omnes,” this lengthy soloistic beginning reverts to plainchant (see Figure 3.5, section 2).

NAWM 3dAnonymous, Mass for Christmas Day, Viderunt omnes (Gradual)

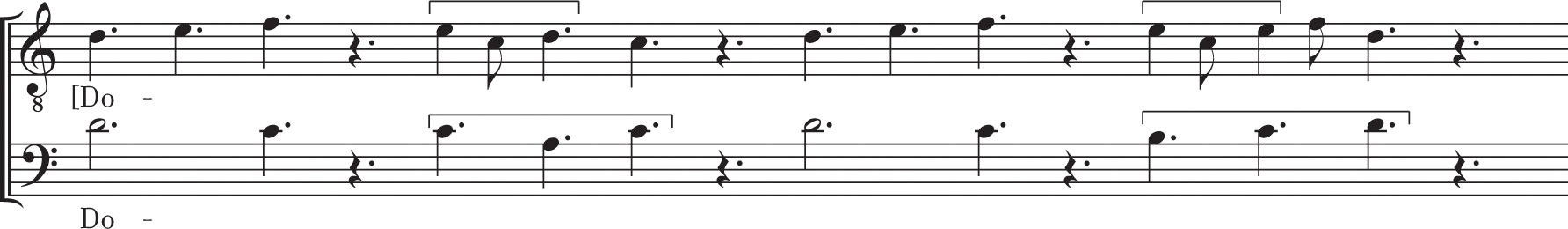

The next section of the Gradual [3] and [4] was sung in two styles, moving from organum to discant on the syllable “Do” of “Dominus,” where a long melisma had appeared in the original chant (compare Example 3.6 with Figure 3.5). Had the singers not quickened the pace of the tenor voice here, the result would have been a work of excessive length. But by singing occasional discant passages where the original chant was melismatic, and placing them alongside sections of plainchant and organum, Leoninus and his colleagues created a piece of manageable size within the context of the liturgy and offered the worshippers a variety of pleasing textures without changing a word or note of the original chant (although they occasionally repeat a phrase to provide structural support for their discant elaboration).

Example 3.5 First section of Viderunt omnes, in organum duplum

More information

Example 3.6 Discant clausula on “do-” of Viderunt omnes

More information

More information

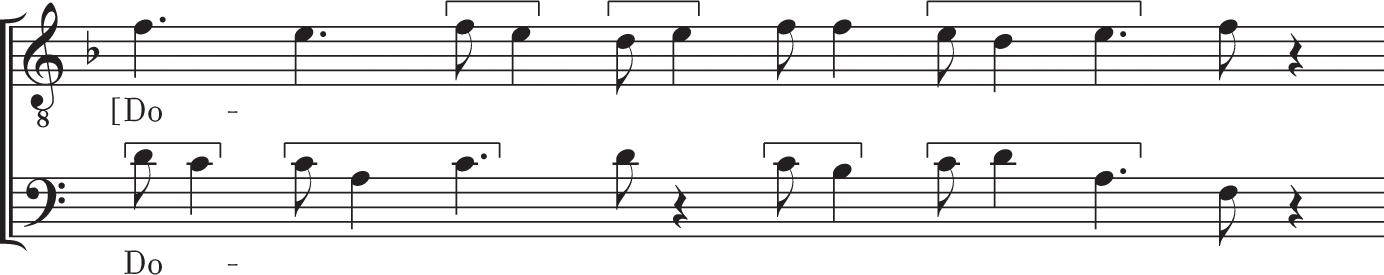

A section in discant style was called a clausula (pl. clausulae), the Latin word for a clause or phrase in a sentence. Discant clausulae are characteristically more consonant than organa and have relatively short phrases and more lively pacing because both voices move in modal rhythm (repeated patterns of long and short notes; see Innovations, p. 56), creating contrast with the surrounding unmeasured sections of organa. Perotinus was credited with composing “very many better clausulae” as he and his contemporaries continued editing and updating the Magnus liber. Hundreds of separate clausulae appear in the same manuscripts as the organa themselves; because some may have been designed to replace the original setting of the same segment of chant, they are sometimes called, collectively, substitute clausulae. One manuscript includes ten clausulae on the word “Dominus” from Viderunt omnes, any one of which could have been used at Christmas Mass. The openings of two of them are shown in Example 3.7 (NAWM 18).

NAWM 18aAnonymous, Clausulae on Dominus, from Viderunt omnes, No. 26

NAWM 18bAnonymous, Clausulae on Dominus, from Viderunt omnes, No. 29

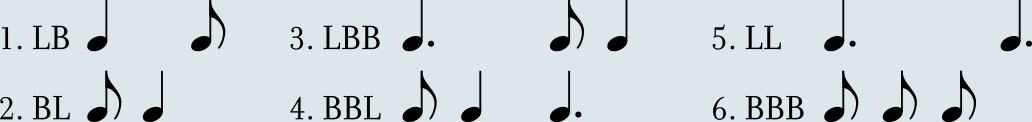

Innovations Modal Rhythm

Innovations Modal Rhythm

It is no coincidence that the earliest solution to the problem of notating rhythm is associated with Paris, particularly with its rising cathedral and its flourishing university (see p. 10). With the recovery of Aristotle’s writings and the reliance on Aristotelian logic, Scholasticism (the dominant intellectual movement of the age) displayed a fascination with order. This fascination led to an interest in classifying rhythms. One significant source for classifying poetic meters, Saint Augustine’s De musica, written in the fourth century, analyzes the motion of poetic meters according to their “music” or “sounding numbers.” (Like Boethius, Augustine considered music to be one of the mathematical arts of the quadrivium.) Borrowing from ancient sources, Augustine says, music is “the art of measuring well.” The crystallization of the six rhythmic modes (shown in Figure 3.6), which correspond roughly to the arrangement of long and short syllables of ancient Latin verse, took place against this background.

Even though Latin poetry of the Middle Ages was no longer organized quantitatively (by the twelfth century, it was defined by stress rather than by syllable length), the theory of the rhythmic modes appears to derive from the principles underlying the measurement of classical poetic meter. It posits that music, like poetry, can be ordered or measured by units of time that have an exact numerical relationship with one another, the long note being twice or three times the duration of the short note, or breve (L and B, respectively, in Figure 3.6). In this way, the new musical practice at Notre Dame, which may have originated in rhythmic patterns to aid in the memorization of organa’s long melismas, was reconciled with the University of Paris curriculum that considered music a branch of mathematics — the science of numbers as they relate to sound. This revolutionary new application of old principles is what allowed the repertory from Notre Dame to be preserved and disseminated across much of Europe, from Spain to Scotland. And from this innovation, the development of musical notation in the West unfolds.

More information

More information

(Photo courtesy of the author.)

Example 3.7 Two substitute clausulae on “Dominus” from Viderunt omnes

a.

More information

b.

More information

Both clausulae exhibit a common trait of discant in Perotinus’s generation: the tenor repeats a rhythmic motive based on one of the rhythmic modes. Because these rhythmic patterns use shorter notes than earlier discant, the tenor melodies were often repeated, though over a longer span of time than the rhythmic pattern itself. These repetitive motives create a sense of coherence for an extended passage, and both types of repetition in the tenor — of rhythm and of melody — gained significance in the motet of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries (see below, p. 58 and Chapter 4).

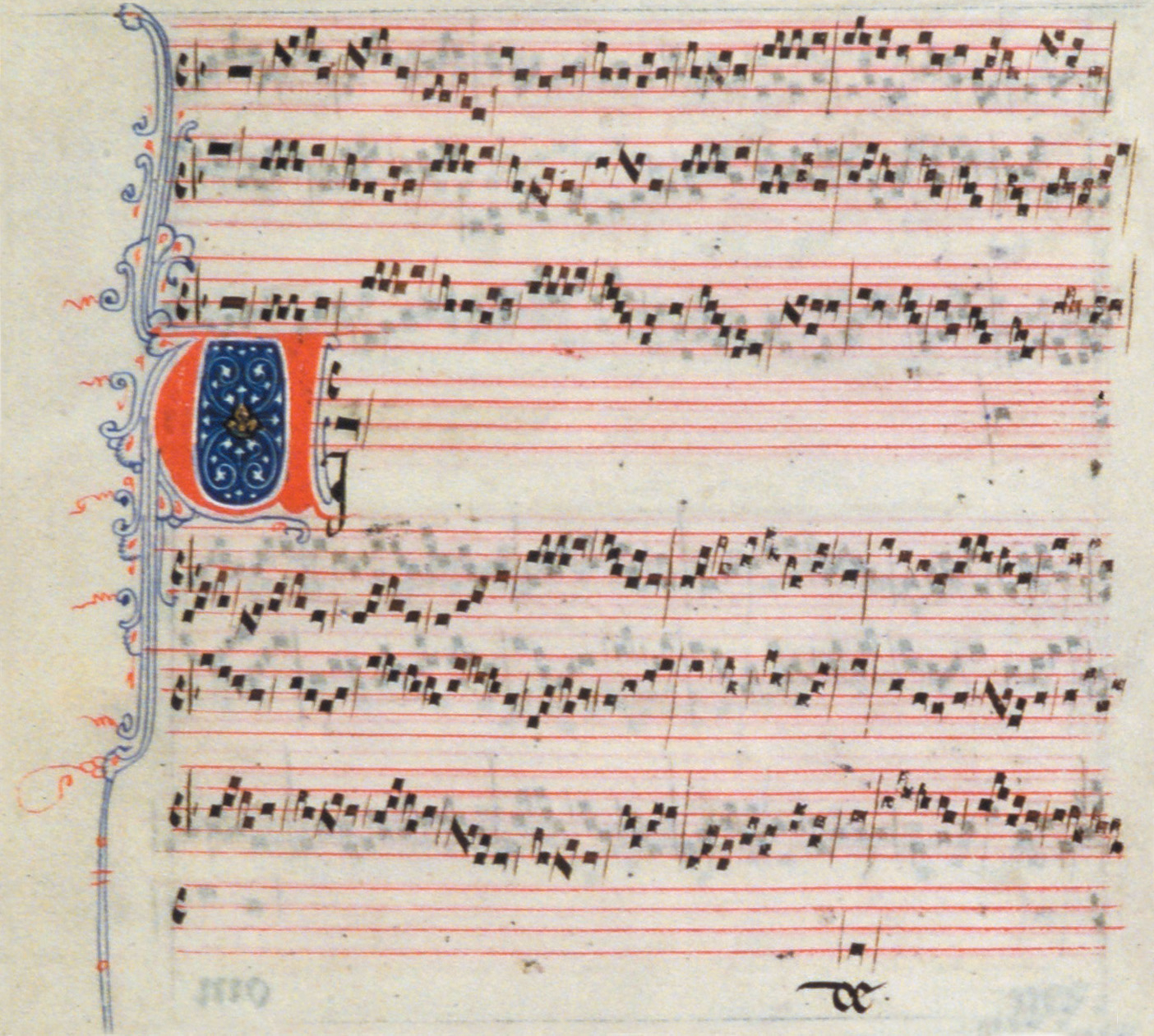

(Firenze, Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana, Ms. Plut. 29.1, c. 2r. Courtesy of the Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali.)

Perotinus “the Great” and his contemporaries expanded organum’s dimensions by increasing the number of voice parts to three and (in two instances) to four. Since the second voice was called the duplum, by analogy the third was called the triplum and the fourth the quadruplum. These same terms also designated the composition as a whole: a three-voice organum came to be called an organum triplum, or simply triplum, and a four-voice organum a quadruplum. One of the two astonishing examples of four-voice organum — which stretches out the first word of the chant to extraordinary melismatic lengths — is the setting ascribed to Perotinus of Viderunt omnes (NAWM 19). Like other works of its kind, it begins in a style of organum with patterned clusters of notes in modal rhythm in the upper voices above very long, unmeasured notes in the tenor (see Figure 3.8 and its partial transcription in Example 3.8). As in the two-voice setting, such passages alternate with sections of discant, of which the longest is again on “Dominus” (not shown here).

NAWM 19Perotinus, Viderunt omnes

The repertory created at Notre Dame was sung for more than a century, from the late twelfth century through the thirteenth. Music historians have long regarded it as the first polyphony to be primarily composed in writing and read from notation rather than improvised or orally composed. But, according to recent research, it was more likely a repertory developing from orality to literacy, or a fluid body of polyphony created by singers and preserved in memory before it was written down. How such a vast and complex repertory was remembered, and how it was written down, are aspects that make this music especially significant in music history.

Example 3.8 Perotinus, Viderunt omnes, opening, with repeating elements indicated by letter