Chapter 1

Anthropology in a Global Age

More information

Two women wearing face masks and face shields stand in a food pantry. One woman hands a packet of crackers to the other woman, who is holding an open bag. A sign behind them reads “Maginhawa Community Pantry.”

Learning Objectives

On the morning of April 14, 2021, Ana Patricia Non, a twenty-six-year-old owner of a small furniture repair business in Manila, capital of the Philippines, filled a bamboo cart with rice, vegetables, vitamins, face masks, and canned goods and rolled it out by a street lamp near her home. On the lamppost, she hung a simple handmade cardboard sign: “Community Pantry: Give What You Can, Take What You Need.” Her country’s COVID-19 infections and deaths were surging again more than a year into the global pandemic. Nearly one-fifth of all Filipinos had lived below the poverty line before the pandemic, struggling to feed their families. Now, the situation was deteriorating rapidly.

More information

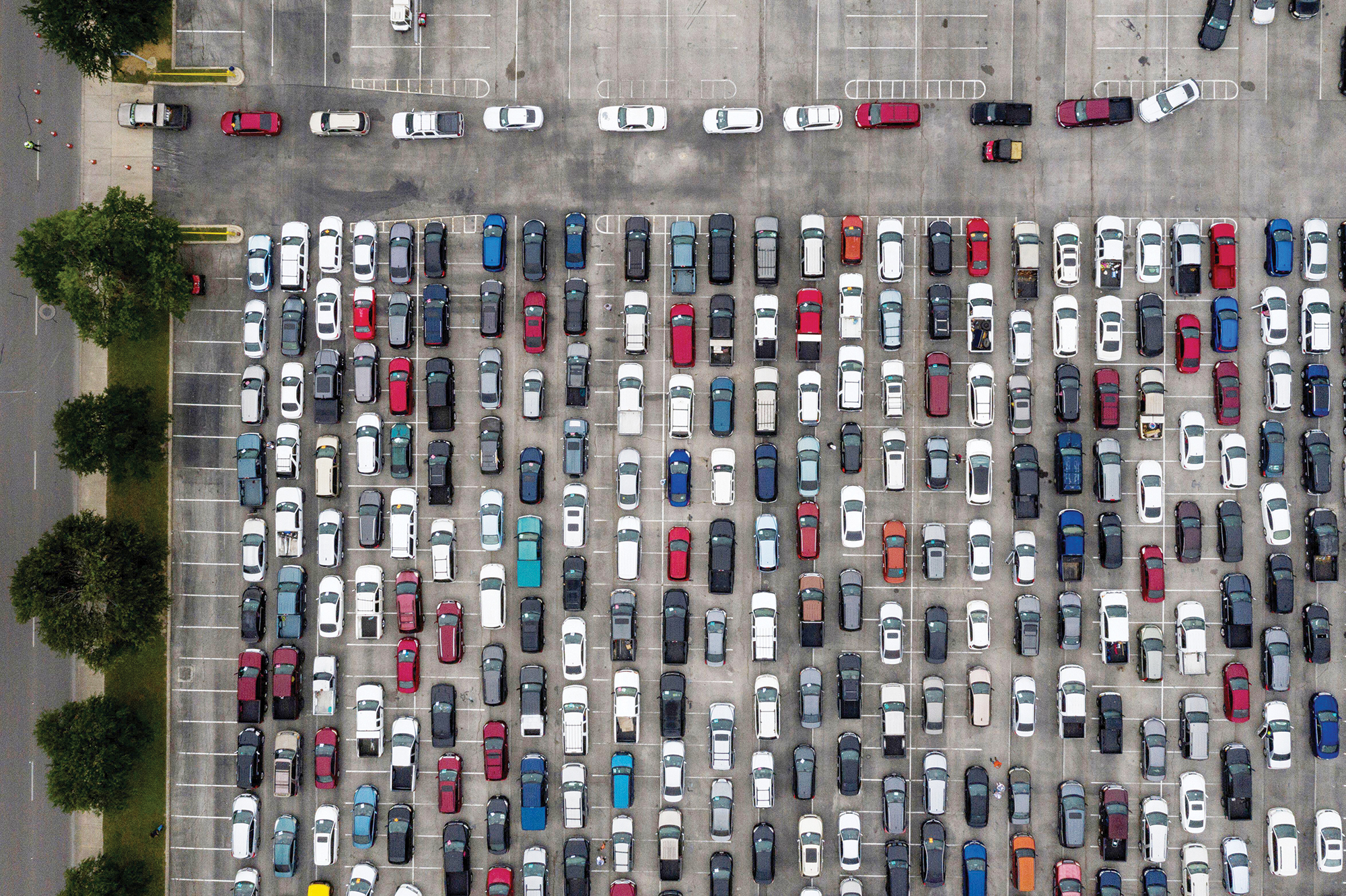

An aerial view of cars lined up in a parking lot. The entire lot is full with cars organized in 26 rows, and a separate line of cars is exiting the parking lot.

Over the course of the day, hungry people began to line up for food. Other neighbors restocked the cart. That night, Non posted about her community pantry on Facebook. By morning, her project had gone viral on social media, inspiring hashtags like #FreeFoodForAll and #MassTestingNow. Over the following days, local fishermen brought their catch. Farmers donated baskets of produce. Within a week, hundreds of other community pantries spontaneously opened across the country as local Filipinos launched a nationwide mass movement to feed their fellow citizens.

More information

The Philippines is highlighted. Manilla is labeled within the Philippines.

The Filipino community pantry movement is one among many grassroots efforts that have arisen to address the effects of the global COVID-19 pandemic on local communities where the coronavirus has exposed long-standing patterns of inequality. In Marseille, France, where a local McDonald’s had once provided rare job opportunities in a poor neighborhood, low-wage workers occupied the restaurant rather than allowing its owner to sell the store. When COVID-19 struck, the workers converted the building into a community food pantry for local residents, over 40 percent of whom had been living below the poverty line even before the arrival of the pandemic.

In Texas, weeks before Thanksgiving in 2020, churches, businesses, and individuals donated food to hundreds of thousands of people waiting in cars lined up for miles at emergency food banks, forced there by unemployment, illness, lack of insurance, and depleted savings. In Philadelphia, neighbors opened over twenty-five street-side community refrigerators stocked with free food to address food insecurity in the city. The level of food insecurity in the United States doubled to 23 percent of all households during the pandemic. Families with children were particularly hard-hit. Perhaps you or someone you know struggled with food insecurity before or during the pandemic.

Never before has the world seen a disease spread across the globe as quickly, or as widely. Of course, never before has the world been so deeply interconnected. In today’s global age, people, ideas, and things move along expansive transportation and communication routes at a speed and in numbers unimaginable only a few years ago. Humans have carried COVID-19 along these same elaborate pathways.

When the city of Wuhan, China, abruptly locked down in January 2020 to prevent the spread of the highly infectious and deadly coronavirus that causes COVID-19, few expected that within months, people in every part of the world would be confronting pandemic conditions. Local communities fought the disease with stay-at-home orders, school closings, travel bans, testing, contact tracing, quarantines, and vaccines. Individuals practiced physical distancing, mask wearing, and handwashing. Despite often heroic efforts over the ensuing years, millions of people had died of COVID-19–related illness and millions more continue to struggle with its long-term effects (World Health Organization 2021). Perhaps you or someone close to you has been affected.

Everywhere the coronavirus has spread, its effects have made visible the many common experiences that humans share in today’s increasingly integrated global economy. Irrespective of country or region, the virus has taken root wherever vulnerable populations lack reliable access to health care, shelter, and food. Rates of illness and mortality have been consistently correlated with age, class, race, ethnicity, and other systems of inequality. Surging global hunger has also become a defining characteristic of the coronavirus pandemic. In 2020, 768 million people—10 percent of the world’s population—were hungry, and 2.38 billion people—30 percent of the world’s population—suffered food insecurity, lacking year-round access to adequate food (United Nations 2021). But in the face of these crises, local communities have mobilized to address the needs of their neighbors.

The stories of the Filipino community pantry movement, the worker uprising in France, and widespread food insecurity in the United States challenge us to think both globally and locally about the effects of the pandemic and, in the process, to consider how closely our lives connect with those of others around the world. The stories also present opportunities to think more deeply about the how the world really works, to understand one another more fully, and perhaps to explore new strategies for living together in this global age.

Today, we encounter and interact with people, ideas, systems, and even viruses around the world in ways that would have been almost unimaginable to previous generations. The iPhone, Facebook, Zoom, and other communication technologies link people instantaneously across the globe. Transnational corporations, international banking, cryptocurrencies, and other economic activities challenge national boundaries. Despite a global pandemic, business elites, low-wage workers, and refugees are on the move within and between countries. Violence, terrorism, and cyberwarfare disrupt lives and political processes. Viruses like COVID-19 travel along elaborate air, rail, sea, and road transportation networks, easily moving within countries and across borders. Humans have had remarkable success at feeding much of a growing world population, yet extreme income inequality continues to increase—both among nations and within them. And increasing human diversity on our doorstep opens possibilities for both deeper understanding and greater misunderstanding. Clearly, the human community in the twenty-first century is being drawn even further into an intense global web of interaction.

More information

Traders steer boats filled with packages of trade goods at the port of Mopti, Mali.

For today’s college student, every day can be a cross-cultural experience. This may manifest itself in the most familiar places: the news you see on television, the music you listen to, the foods and beverages you consume, the people you date, the classmates you study with, the religious communities you belong to. Today, you can realistically imagine contacting any of your 8 billion co-inhabitants on the planet. You can read their posts on Instagram and watch their videos on YouTube. You can visit them. You wear clothes that they make. You make movies that they see. You can learn from them. You can affect their lives. How do you meet this challenge of deepening interaction and interdependence?

Anthropology provides a unique set of tools, including strategies and perspectives, for understanding our rapidly changing, globalizing world. Most of you are already budding cultural anthropologists without realizing it. Wherever you may live or go to school, you are probably experiencing a deepening encounter with the world’s diversity.

Whether our field is business or education, medicine or politics, we all need a skill set for analyzing and engaging our multicultural and increasingly interconnected world and workplaces. Cultural Anthropology: A Toolkit for a Global Age introduces the anthropologist’s tools of the trade to help you better understand and engage the world as you move through it and, if you so choose, apply those strategies to the challenges confronting us and our neighbors around the world. To begin our exploration of anthropology, we’ll consider four key questions: