THE ROMAN LITURGY

Gregorian chant is music for Christian religious observances. Tunes vary from simple recitation to elaborate melodies, depending on their role in the liturgy. Thus understanding chant requires some knowledge of the services in which it is used. The Roman liturgy is complex, resulting from a long history of addition and codification that was largely unknown to those who participated in services. This historical framework can help us comprehend both the shape of the liturgy and the diversity of chant.

PURPOSE OF THE LITURGY

The role of the church was to teach Christianity and to aid in saving souls. Over the centuries, as missionaries spread the faith across Europe from Spain to Sweden, they taught the precepts of church doctrine: the immortality of each person’s soul; the Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit; Jesus’s crucifixion, resurrection, and ascension into heaven; salvation and eternal heavenly life for those judged worthy; and damnation in hell for the rest. One purpose of religious services was to reinforce these lessons for worshippers, making clear the path to salvation through the church’s teachings. This purpose was served chiefly by the liturgy, the texts that were spoken or sung and the rituals that were performed during each service. The role of music was to carry those words, accompany those rituals, and inspire the faithful.

At the same time, the words, prayers, and singing were directed to God, who was in some respects the primary audience. The daily cycle of services in monasteries and convents, attended only by the participants, reflected the belief that humans on earth, like the angels in heaven, should offer unceasing praises to God. Thus the liturgy and music of the Roman Church had dual aims: addressing God and reinforcing the faith of those in attendance.

CHURCH CALENDAR

Part of teaching Christianity was repeating the stories of Jesus and of the saints, exemplary Christians whom the church raised up as models of faith or action. Every year, the church commemorated each event or saint with a feast day, in a cycle known as the church calendar. The most important feasts are Christmas (December 25), marking Jesus’s birth, and Easter, celebrating his resurrection and observed on the Sunday after the first full moon of spring. Both are preceded by periods of preparation and penitence: Advent begins four Sundays before Christmas, and Lent starts on Ash Wednesday, forty-six days before Easter. Although much of each religious service is the same at every observance, other aspects change with the day or season.

MASS

The most important service in the Roman Church is the Mass, which evolved from commemorations of the Last Supper of Jesus with his disciples (Luke 22:14–20). The central act, shown in Figure 3.1, is a symbolic reenactment of the Last Supper in which a priest consecrates bread and wine, transformed in essence into the body and blood of Christ, and offers them to worshippers in communion. This ritual fulfills Jesus’s commandment to “do this in remembrance of me” (1 Corinthians 11:23–26) and reminds all present of his sacrifice for the atonement of sin. Over time, other ritual actions and words were added, including prayers, Bible readings, and psalm-singing. The Mass is performed every day in monasteries, convents, and major churches, on Sundays in all churches, and more than once on the main feast days.

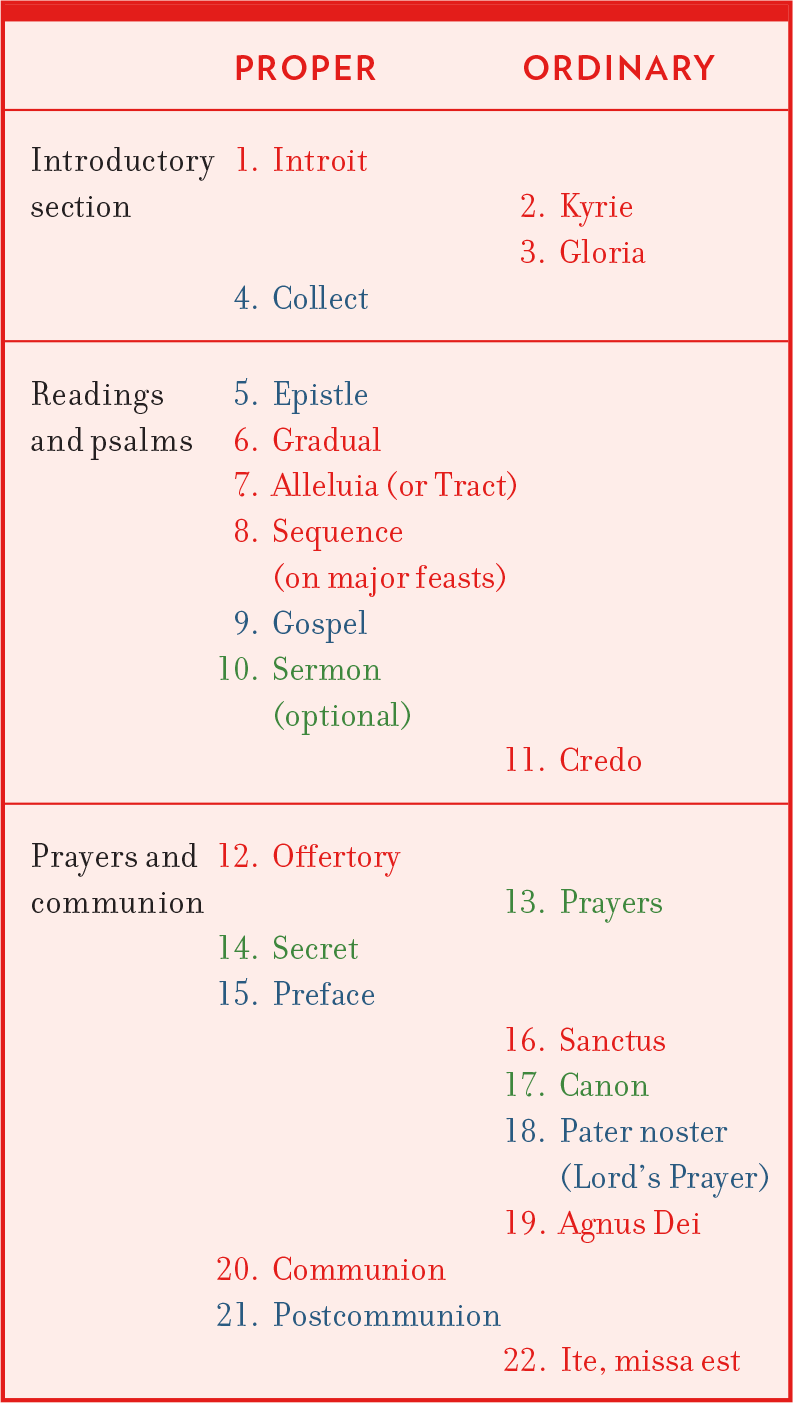

The Mass as it stood by the eleventh century is described in Music in Context: The Experience of the Mass (pp. 44–45). (For the complete Mass for Christmas Day, see NAWM 3.) The most important musical items, each sung to an independent melody by the choir and its soloists, are shown in red in Figure 3.2. The other items were either intoned (recited to a simple melodic formula) or spoken by the priest or an assistant.

Proper and Ordinary The texts for certain parts of the Mass vary from day to day and are collectively called the Proper of the Mass. The texts of other parts, called the Ordinary of the Mass, do not change, although the melodies may vary. The Proper chants are called by their function, the Ordinary chants by their initial words. The sung portions of the Ordinary were originally performed by the congregation, but were later taken over by the choir, which was all male (or, in convents, all female).

The Experience of the Mass

The Mass was the focal point of medieval religious life. For the largely illiterate populace, it was their main source of instruction, where they were told what to believe and how to live. It was up to the church to present those fundamental truths in a way that would engage and inspire, gripping not only the mind but also the heart.

The building where Mass was celebrated was designed to evoke awe. Whether a simple church or a grand cathedral, it was likely to be the tallest structure most people would ever enter. The high ceiling and windows drew the eye heavenward. Pillars and walls were adorned with sculptures, tapestries, or paintings depicting pious saints, the life of Jesus, or the torments of hell, each image a visual sermon. In these resonant spaces, the spoken word was easily lost, but singing carried words clearly to all corners.

European Christians, especially in central and northern Europe, were not long removed from old pagan customs of propitiating the gods to ensure good crops or prevent misfortune, and they looked to Christian observances to serve the same role. Life for most was hard, and with the constant threat of disease, famine, and war, average life expectancy was under thirty years. Worship in a well-appointed church, conducted by clergy arrayed in colorful vestments, using chalices, crosses, and books bedecked with gold, and singing heavenly chants, offered not only an interlude of beauty, but a way to please God and secure blessings in this life and the next.

In such a space, the Mass begins with the entrance procession of the celebrant (the priest) and his assistants to the altar, incense wafting through the air. The choir sings a psalm, the Introit (from Latin for “entrance”). After all are in place, the choir continues with the Kyrie, whose threefold invocations of Kyrie eleison (Lord have mercy), Christe eleison (Christ have mercy), and Kyrie eleison capture the hopes of the worshippers and symbolize the Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The Greek words and text repetitions reflect the Kyrie’s origins in a Byzantine processional litany, a form in which participants repeat a short prayer in response to a leader. On Sundays and feast days (except in Advent and Lent), there follows the Gloria, or Greater Doxology, a formula of praise to God that encapsulates the doctrine of the Trinity and again asks for mercy. The priest then intones the Collect, a prayer on behalf of all those present.

After these introductory items, the next section of the Mass focuses on Bible readings, florid chants, and church teachings. Here the service offers instruction, familiarizing worshippers (at least, those who understand Latin) with the Scriptures and central tenets of the faith. First the subdeacon intones the Epistle for the day, a passage from the letters of the apostles. Next come two elaborate chants sung by a soloist or soloists with responses from the choir: the Gradual (from Latin gradus, “stairstep,” from which it was sung) and the Alleluia (from the Hebrew Hallelujah, “praise God”), both based on psalm texts. These chants are the musical high points of the Gregorian Mass, performed when no ritual is taking place and text and music are the center of attention. On some days in the Easter season, the Gradual is replaced by another Alleluia as a sign of celebration; during Lent, the joyful Alleluia is omitted or replaced by the more solemn Tract, a florid setting of several verses from a psalm. On some occasions the choir sings a sequence after the Alleluia. The deacon then intones the Gospel, a reading from one of the four books of the New Testament that relate the life of Jesus. The priest may offer a sermon. On Sundays and important feast days, this section of the Mass concludes with the Credo, a statement of faith summarizing church doctrine and telling the story of Jesus’s incarnation, crucifixion, and resurrection.

Red: Sung by choir Blue: Intoned Green: Spoken

Next the priest turns from words to actions. As he prepares the bread and wine for communion, the choir sings the Offertory, a florid chant on a psalm. There follow spoken prayers and the Secret, read in silence by the priest. The Preface, a dialogue between priest and choir, leads into the Sanctus (Holy, holy, holy), whose text begins with the angelic chorus of praise from the vision of Isaiah (Isaiah 6:3). The priest speaks the Canon, the core of the Mass that includes the consecration of bread and wine. He sings the Lord’s Prayer, and the choir sings the Agnus Dei (Lamb of God), which like the Kyrie was adapted from a litany. In the medieval Mass, the priest then takes communion, consuming the bread and wine on behalf of all those assembled, rather than sharing it with everyone as was the custom earlier (and again today). After communion, the choir sings the Communion, based on a psalm. The priest intones the Postcommunion prayer, and the priest or deacon concludes the service by singing Ite, missa est (Go, it is ended), with a response by the choir; from this phrase came the Latin name for the entire service, Missa, which became the English “Mass.” When the Gloria is omitted, Ite, missa est is replaced by Benedicamus Domino (Let us bless the Lord).

Throughout the Mass, the music serves both to convey the words and engage the worshippers.

Evolution of the Mass Early forms of the ceremony that became the Mass fell into two parts. The community heard prayers, readings from the Bible, and psalms, often followed by a sermon. Then the catechumens, those receiving instruction in Christian beliefs but not confirmed in the church and thus unable to receive communion, were dismissed, ending the first part. The faithful offered gifts to the church, including bread and wine for the communion. The priest said prayers of thanksgiving, consecrated the bread and wine, and gave communion, accompanied by a psalm. After a final prayer, he dismissed the faithful.

From this outline, the Mass gradually emerged (see Music in Context: The Experience of the Mass). The opening greeting was expanded into an introductory section. The first part of the early Mass became a section focused on Bible readings and psalms; the final part centered on offerings and prayers leading to communion. The main musical items of the Ordinary—the Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei—were relatively late additions. Ironically, these are now the portions most familiar to musicians, because their texts do not change and because almost all compositions called “mass” from the fourteenth century onward are settings of these portions only.

PROPER FOR CHRISTMAS MASS

While the Ordinary chants are a familiar part of every Mass, it is the Proper that links the service to a particular day of the church year and gives it a more specific meaning. For example, in the Mass for Christmas Day (NAWM 3), each element of the Proper addresses the nativity of Jesus or places it in a broader theological context. Some of the texts are drawn from psalms or other books of the Hebrew Scriptures, and it is through their juxtaposition with each other and with New Testament passages that a Christian message emerges. The Introit (NAWM 3a) announces the birth of a child who shall rule, using words from Isaiah 9:6 that Christians understood to prophesy Jesus’s birth, and continues with a celebratory psalm verse. The Gradual (NAWM 3d) uses verses from the same psalm that declare the revelation of salvation to all peoples, and the Alleluia (NAWM 3e) hails this sanctified day when a great light descended to earth. These elaborate and florid chants come between the two main readings in this Mass; the Epistle, from the letter to the Hebrews (1:1–12), relates the importance of Jesus as the son of God, and the Gospel, from John 1:1–14, depicts Jesus as the Word of God born into human form. The Offertory (NAWM 3g) sets psalm verses that acknowledge God’s dominion over heaven and earth, and the Communion (NAWM 3j) returns to the opening words of the Gradual. Together, these chants celebrate Jesus’s birth and summarize the Christian theology that regards him as Savior, Lord, son of God, Word of God, and light of the world.

NAWM 3a Anonymous, Mass for Christmas Day: Introit: Puer natus est nobis

NAWM 3d Anonymous, Mass for Christmas Day: Gradual: Viderunt omnes

NAWM 3e Anonymous, Mass for Christmas Day: Alleluia Dies sanctificatus

NAWM 3g Anonymous, Mass for Christmas Day: Offertory: Tui sunt caeli

NAWM 3j Anonymous, Mass for Christmas Day: Communion: Viderunt omnes

THE OFFICE

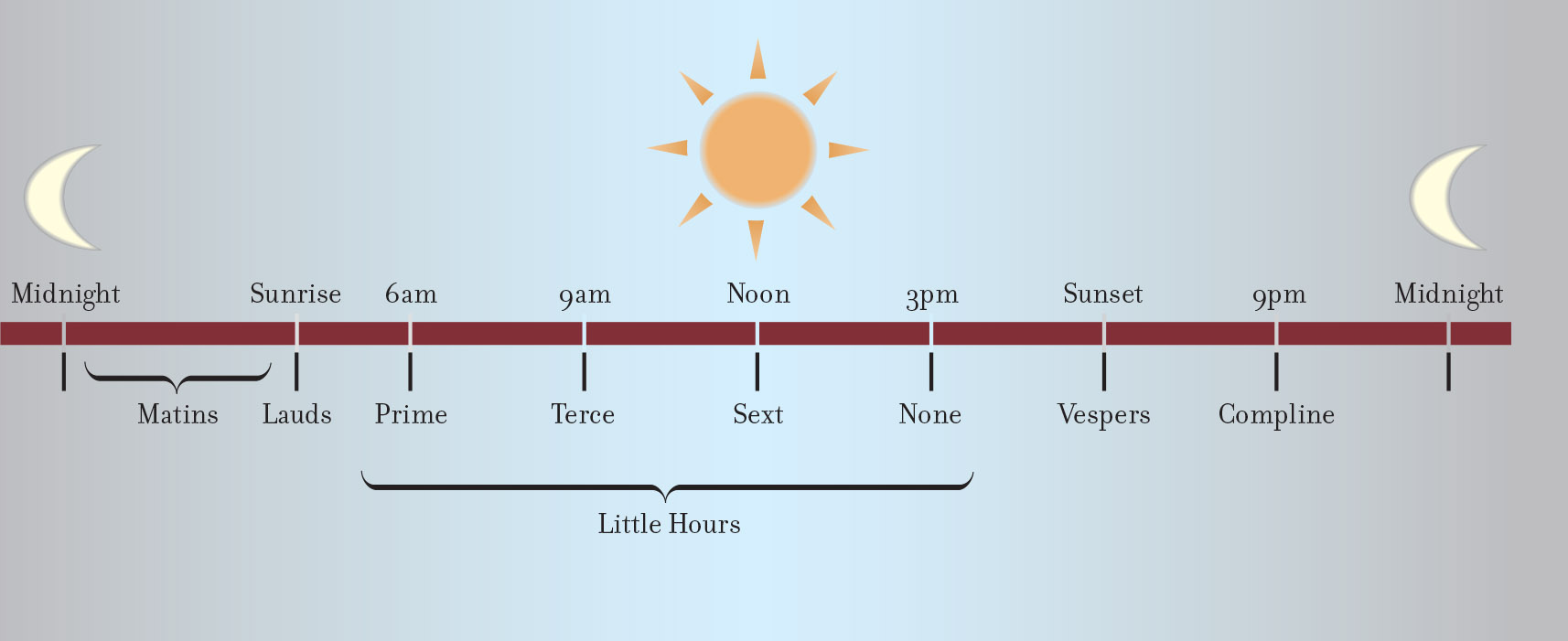

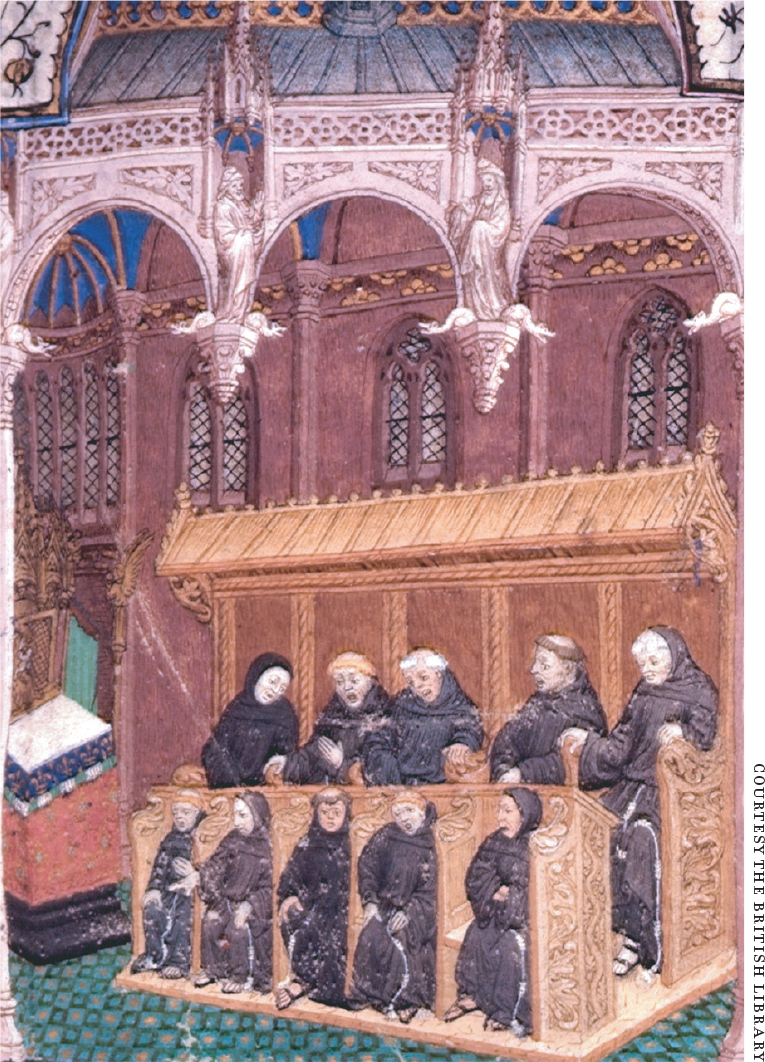

Early Christians often prayed and sang psalms at regular times throughout the day and night, in private or public gatherings. These observances were codified in the Office, a series of eight services that since the early Middle Ages have been celebrated daily at specified times, as shown in Figure 3.3. The Office was particularly important in monasteries and convents, where Mass and Office observances occupied several hours every day and night. All members of the community sang in the services. Figure 3.4 depicts this central focus of monastic life.

Monasteries and convents in the Roman Church followed the liturgy for the Office codified in the Rule of St. Benedict (ca. 530), a set of instructions on running a monastery. The Office liturgy for churches outside monasteries differed in some respects, and both texts and music varied considerably over time and from place to place, resulting in a less stable and more local repertory of chants for the Office than for the Mass. Office observances include several psalms, each with an antiphon, a chant sung before and after the psalm; lessons (Bible readings) with musical responses called responsories; hymns; canticles, poetic passages from parts of the Bible other than the Book of Psalms; and prayers. Over the course of a normal week, all 150 psalms are sung at least once. The most important Office services, liturgically and musically, are Matins, Lauds, and Vespers.

LITURGICAL BOOKS

Texts and music for services were gathered in books, copied by scribes in the Middle Ages and later printed under church authority. Texts and some music for the Mass are in the Missal, and the chants sung by the choir in the Gradual. Texts and some music for the Office are collected in the Breviary, and the music for the choir in the Antiphoner.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, monks of the Benedictine Abbey of Solesmes (see pp. 30–31) prepared modern editions of the Gradual and Antiphoner and issued the Liber usualis (Book of Common Use), which contains the most frequently used texts and chants for the Mass and Office. The Solesmes editions were adopted as the official books for use in services and are used in most recordings of Gregorian chant. Although these editions reflect a modern standardization of a repertory that varied over time and from place to place, they provide a good introduction to Gregorian chant and will serve as the basis for the discussion here and in NAWM 3 (Mass) and NAWM 4 (Vespers).

- church calendar

In a Christian rite, the schedule of days commemorating special events, individuals, or times of year.

- Mass

(from Latin missa, “dismissed”) (1) The most important service in the Roman Church. (2) A musical work setting the texts of the Ordinary of the Mass, typically Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei. In this book, as in common usage, the church service is capitalized (the Mass), but a musical setting of the Mass Ordinary is not (a mass).

- Proper of the Mass

(from Latin proprium, “particular” or “appropriate”) Texts of the Mass that are assigned to a particular day in the church calendar.

- Ordinary of the Mass

(from Latin ordinarium, “usual”) Texts of the Mass that remain the same on most or all days of the church calendar, although the tunes may change.

- Office

(from Latin officium, “obligation” or “ceremony”) A series of eight prayer services of the Roman Church, celebrated daily at specified times, especially in monasteries and convents; also, any one of those services.

- antiphon

(1) A liturgical chant that precedes and follows a Psalm or canticle in the Office. (2) In the Mass, a chant originally associated with antiphonal psalmody; specifically, the Communion and the first and final portion of the Introit.

- responsory

Responsorial chant used in the Office. Matins includes nine Great Responsories, and several other Office services include a Short Responsory.

- canticle

Hymn-like or psalm-like passage from a part of the Bible other than the Book of Psalms.

- Introit

(from Latin introitus, “entrance”) First item in the Mass Proper, originally sung for the entrance procession, comprising an antiphon, psalm verse, Lesser Doxology, and reprise of the antiphon.

- Kyrie

(Greek, “Lord”) One of the five major musical items in the Mass Ordinary, based on a Byzantine litany.

- Gloria

(Latin, “Glory”) Second of the five major musical items in the Mass Ordinary, a praise formula also known as the Greater Doxology.

- Greater Doxology

(Latin, “Glory”) Second of the five major musical items in the Mass Ordinary, a praise formula also known as the Greater Doxology.

- Gradual

(from Latin gradus, “stairstep”) Item in the Mass Proper, sung after the Epistle reading, comprising a respond and verse. Chant graduals are normally melismatic in style and sung in a responsorial manner, one or more soloists alternating with the choir.

- Alleluia

Item from the Mass Proper, sung just before the Gospel reading, comprising a respond to the text “Alleluia,” a verse, and a repetition of the respond. Chant alleluias are normally melismatic in style and sung in a responsorial manner, one or more soloists alternating with the choir.

- Tract

(from Latin tractus, “drawn out”) Item in the Mass Proper that replaces the Alleluia on certain days in Lent, whose text comprises a series of psalm verses.

- sequence

(from Latin sequentia, “something that follows”) (1) A category of Latin chant that follows the Alleluia in some Masses. (2) Restatement of a pattern, either melodic or harmonic, on successive or different pitch levels.

- Credo

(Latin, “I believe”) Third of the five major musical items in the Mass Ordinary, a creed or statement of faith.

- Offertory

Item in the Mass Proper, sung while the Communion is prepared, comprising a respond without verses.

- Sanctus

(Latin, “Holy”) One of the five major musical items in the Mass Ordinary, based in part on Isaiah 6:3.

- Agnus Dei

(Latin, “Lamb of God”) Fifth of the five major musical items in the Mass Ordinary, based on a litany.

- Communion

Item in the Mass Proper, originally sung during communion, comprising an antiphon without verses.