SECTION OBJECTIVES

- Describe how viruses infect cells and cause disease.

- Define transmission, host range, and tissue tropism.

- Describe the different classes of viral genomes and give an example of each.

SECTION OBJECTIVES

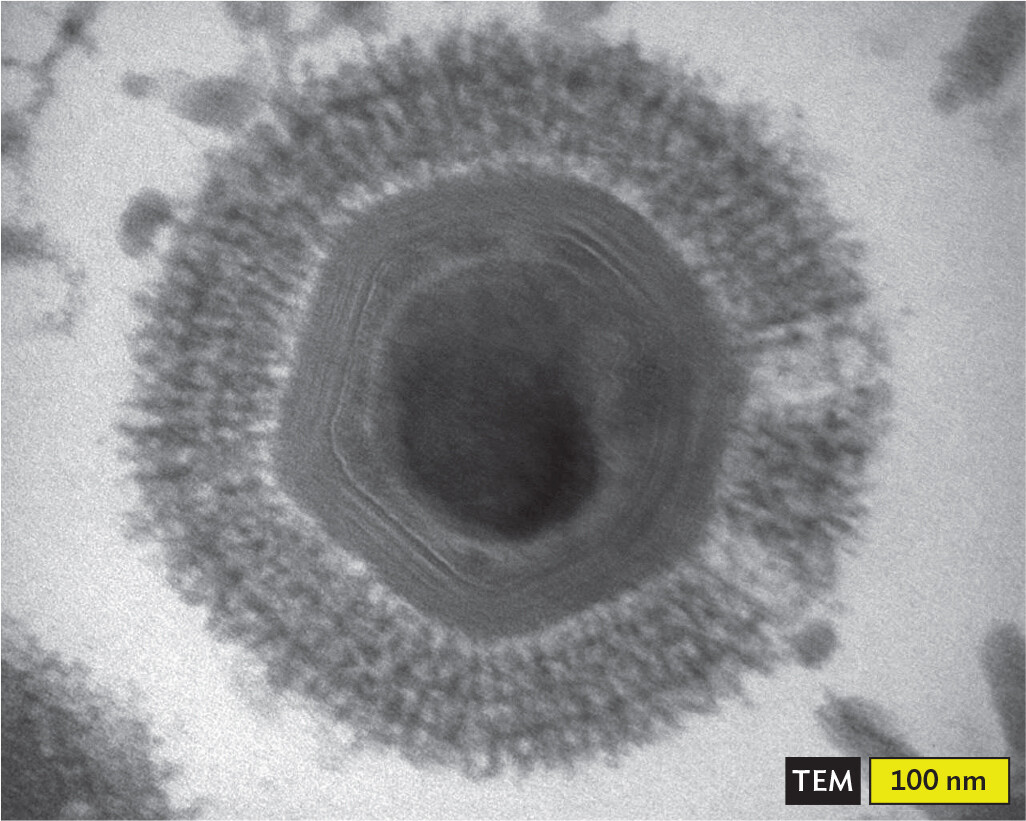

A virus is a noncellular particle with a genome contained by a capsid (protein coat). Viruses take over a cell to manufacture progeny—they require a host cell to reproduce. The term “virus” refers to the particles and their replication cycle, whereas the term virion refers specifically to the structure of the virus particle. Viruses are ubiquitous, infecting every taxonomic group of organisms, including bacteria, eukaryotes, and archaea. For example, the “giant” virus mimivirus infects amebas (Figure 12.1). Amebas phagocytose the mimivirus particle as they do with bacteria they eat (phagocytosis is described in Chapter 5). But once ingested, the virus takes over the ameba’s cytoplasm, forming intracellular “virus factories” that generate more virus particles.

A transmission electron micrograph of a Mimi virus within an ameba. The transmission electron micrograph shows the hexagonal structure of the Mimi virus with a thick fuzzy outer covering. There is a solid dark circular structure at the center of the virus. The virus, including the fuzzy outer covering, is about 300 nanometers in diameter. The hexagon is about 250 nanometers wide and the outer borders of the hexagon are about 100 nanometers in length on each side.

Viruses are part of our daily lives. Children are infected by many seasonal viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, influenza virus A, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). College students frequently experience respiratory pathogens such as rhinovirus (the common cold) and Epstein-Barr virus (infectious mononucleosis), as well as sexually transmitted viruses such as herpes simplex virus (HSV) and human papillomavirus (HPV) that cause cutaneous warts, genital warts, and genital cancers. Viruses also impact human industry; for example, bacteriophages (literally, “bacteria eaters”) infect industrial cultures of Lactococcus during the production of yogurt and cheese. Plant pathogens such as cauliflower mosaic virus and rice dwarf virus cause major losses in agriculture.

And yet, viruses have made astonishing contributions to medical research and biotechnology. Bacteriophages are used routinely as cloning vectors, small genomes into which foreign genes can be inserted and cloned for gene technology. Some of the most lethal human viruses, such as HIV, have been used to make harmless vectors for human gene therapy.

In natural environments, viruses fill important niches in all ecosystems. Viruses limit the population density of hosts, such as marine algae. Algal blooms grow so large that they show up in satellite photos from space; only viruses can dissipate such blooms. Because virus infection dissipates dense populations, viruses select for host diversity. Each viral species has a limited host range and requires a critical population density to sustain the chain of infection. This population is, however, smaller than that sustainable by the nutrient resources in the absence of virus. Thus, a given algal species can increase only so much before its bloom dissipates. The resources then support other species resistant to the given virus (but susceptible to other viruses). Thus, viruses prevent the dominance of any one host species. From bacteriophages in our colon to cold-tolerant viruses of Antarctica, viruses promote ecosystem diversity.

Our concept of a virus has developed over the past centuries. In the late eighteenth century, microbiologists puzzled over infectious agents that passed through a filter with pores too small to permit bacterial cells. The Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck (1851–1931) proposed that a “virus” was an infectious “fluid.” But the “fluid” turned out to consist of small infectious particles that we now refer to as virions.

When the first viruses were discovered, they were defined as nonliving. The viruses known at that time lacked metabolism to use energy or conduct biosynthesis, and certain viruses, such as tobacco mosaic virus, could be crystallized like inert chemicals. But some microbiologists have questioned this position. After all, bacteria such as Clostridium and Bacillus species form endospores that can remain viable for thousands of years. The endospores exist as inert particles, like a virus, but they can germinate outside any host cell. Other kinds of bacteria, such as Rickettsia and Chlamydia, can grow only within a host cell. These obligate intracellular pathogens develop inert spore-like forms that survive outside the host; these forms are comparable to virus particles, except that they possess ribosomes. The question of whether viruses are living organisms remains contested. However, the possession of ribosomes is considered a key requirement for existence as a cell.

The ancient origin of viruses remains a mystery, but the form of modern viruses suggests three intriguing models with implications for human health.

Another startling discovery about viral genomes—both large and small—is that many have been incorporated into the human genome, contributing a substantial part of our own DNA sequence (described in Section 12.6). Such “endogenous viruses” may even produce proteins essential for human function. Viral evolution tells us much about human evolution.

The effects of viral disease arise from the replication of viruses within host cells, which either destroys or debilitates the cells. Viruses also induce host responses that debilitate the host, such as overreaction by the immune system (see Chapters 15 and 16). Some viruses alter host cell genomes to cause cancer, such as leukemia caused by human T-lymphotrophic virus (HTLV) and the head, neck, and genital cancers caused by human papillomavirus (HPV; see Section 12.4).

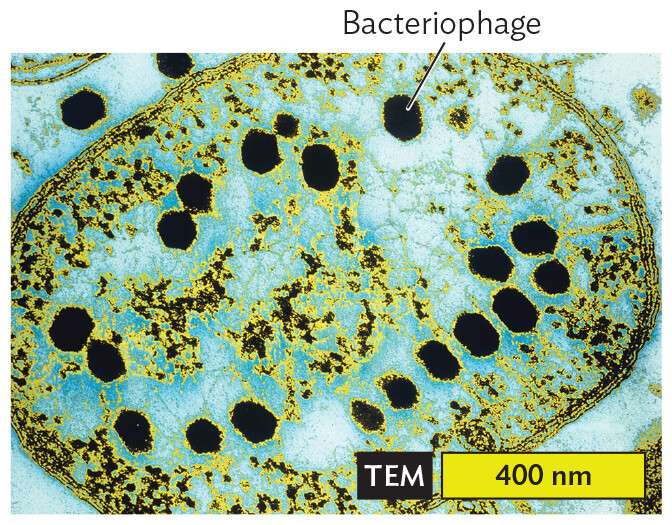

The human gut teems with bacteriophages (phages), viruses that infect bacteria. An example is phage T2, which infects Escherichia coli (Figure 12.2A). Most bacteriophages insert their genome into the host cell, leaving the empty capsid outside. Within the bacterial cytoplasm, the phage genome directs the replication of progeny virions. The virions are released when the host cell lyses. Bacteriophages are being studied for their use in “phage therapy,” the practice of applying a bacteriophage to infect and kill antibiotic-resistant bacteria. For example, in 2017 a patient suffering from Mycobacterium abscessus infection was successfully treated with engineered “mycophages” that infect the pathogen. In the future, phages may be engineered for personalized treatment of various bacterial infections.

A transmission electron micrograph of bacteriophage T 2 particles within an E coli cell. The E coli cell has an oval shaped structure with a dark membrane. brown and yellow tiny dots are distributed in clumps throughout the cytoplasm. There are also several larger, hexagonal darkly staining structures. These are the T 2 bacteriophages. Each bacteriophage is about 70 micrometers across.

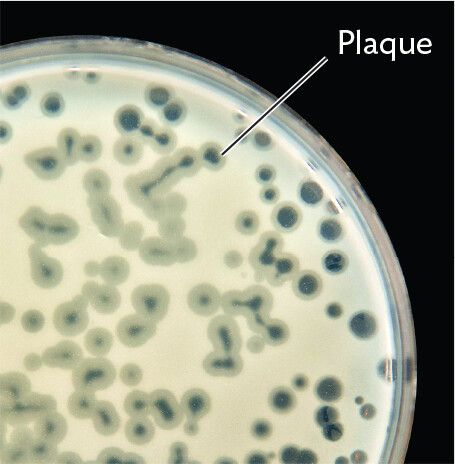

A photo of plaques of lysed cells within a lawn of bacteria on an agar plate. The photo shows a portion of the plate. The lawn of bacteria is an opaque, grey to white film across the entire plate. Transparent circles are scattered throughout the lawn. These are plaques of lysed cells.

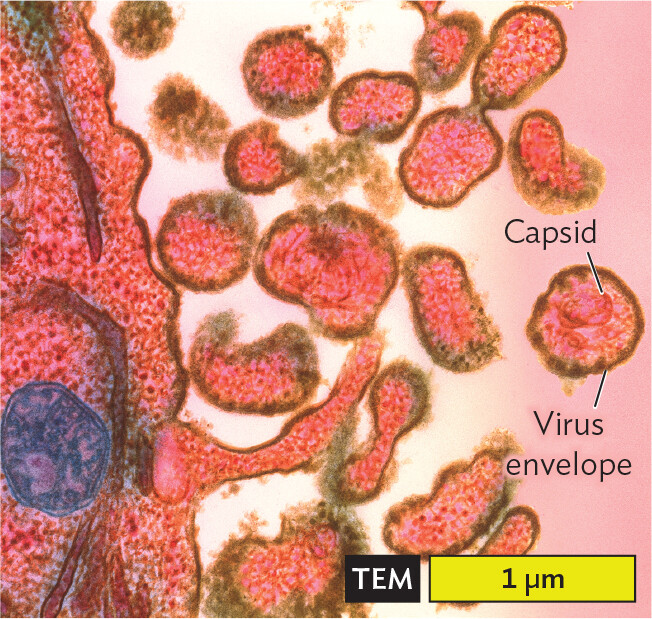

A transmission electron micrograph of Measles virions budding out of human cells. A portion of a human cell is seen, it is larger than 5 micrometers in length and extends beyond the view of the micrograph. Circular and irregularly shaped virions are pushing outward from the edge of the human cell. The human cell membrane is distorted as this occurs. The circular virions each have a diameter of about 0.5 micrometer. The outside of the virion is the capsid. A darkly staining, thick layer around the capsid is the virus envelope.

A photo of a child infected with measles. A rash of pale red spots covers the child’s skin. Some are clumped so close together that they appear continuous.

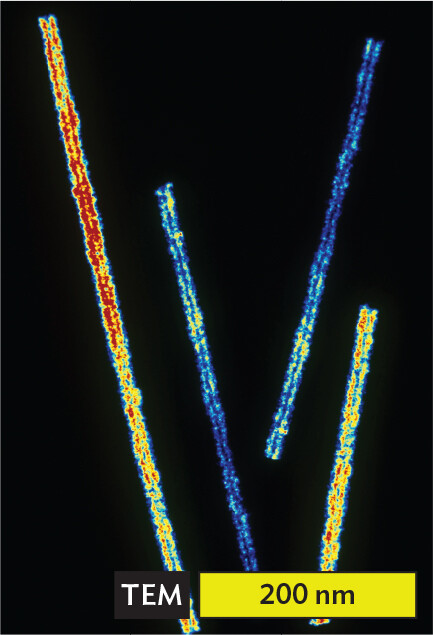

A transmission electron micrograph of tobacco mosaic virus particles. The particles are rod shaped and colorful against a black background. Each particle is between 200 to 250 nanometers long and about 10 nanometers wide. They have straight edges.

A photo of a tomato leaf infected by tobacco mosaic virus. There is a green leaf with a broad, rounded base that comes to a point. There is a vein traveling through the center, and side veins along the midline. The veins are angled diagonally up and out. There are irregular yellowish patches on the leaf surface.

In the lab, phages can be observed in a Petri dish as a plaque, a clear spot against a lawn of bacterial cells (Figure 12.2B). The bacteria grow to completely cover the surface of the agar medium, rendering it opaque—except where bacteria are lysed by phages. Each plaque arises from a single virion or bacteriophage. The bacteriophage lyses a host cell and spreads progeny to infect adjacent cells. Eventually, enough bacterial cells are lysed, making the plaque visible to the naked eye. Plaques can be counted as representing individual infective virions from a phage suspension.

An example of a virus that infects humans is measles virus (Figure 12.2C). The measles virus has an envelope that is derived from the host cell plasma membrane when the virus exits the host cell. When the virus enters a new host cell, the envelope fuses with the host cell plasma membrane, releasing the viral contents into the cell’s cytoplasm. After replicating within the infected cell, newly formed measles virions become enveloped by host cell membrane as they bud out of the host cell. The spreading virus generates a rash of red spots on the skin of infected patients (Figure 12.2D). Untreated cases of measles can be fatal (1 in 500 cases).

Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) infects a wide range of plant species, its virions accumulating to high numbers within plant cells (Figure 12.2E). The progeny virions then travel through interconnections to neighboring cells. Infection by TMV results in mottled leaves and stunted growth (Figure 12.2F). Plant viruses cause major economic losses in agriculture worldwide.

As new virions are produced, these virus particles need to find new cells to infect—and ultimately a new host. The process of reaching and infecting a new host is called transmission. Different viruses have different mechanisms and efficiencies of transmission. For example, the measles virus is transmitted by droplets of respiratory fluid lingering in the air. Measles transmission is highly efficient. By contrast, HIV is transmitted via blood or sexual contact. Transmission of HIV is relatively inefficient, especially via sexual contact; multiple contacts may occur before HIV infection is established in a new host.

Each species of virus infects a particular group of host species, known as the host range. Some viruses can infect only a single species; for example, HIV infects only humans. Close relatives of humans, such as the chimpanzee, are not infected, although they are susceptible to a virus that shares ancestry with HIV, simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV). In contrast, West Nile virus, transmitted by mosquitoes, has a much broader host range, including many species of birds and mammals.

The term tissue tropism refers to the range of tissue types a virus can infect. Some viruses have broad tropism; for example, Ebola virus infects many different tissues throughout the body. Other viruses have a narrow tropism; for example, rabies virus specifically infects nervous tissues, whereas influenza virus specifically infects cells of the respiratory epithelium. Both tropism and host range depend on various host factors, most importantly the surface receptor molecules—typically, the specific proteins on a cell surface that the virus particle can bind to. For example, avian strains of influenza virus (also known as the avian flu) bind effectively to the host cell receptors in birds, but those viruses bind less effectively to receptors in the upper respiratory tissues of humans.

In all cases, viruses use a relatively small number of virus-encoded proteins to commandeer the metabolism of their hosts. This situation has profound consequences for medical therapy:

Fortunately, many viruses, such as those that cause colds and influenza, are soon eliminated by a healthy immune system. But others, such as HIV, may lead to a lifetime infection because they can hide within host cells in a latent state, where they are inaccessible to the host immune system. Virology supports the old adage that prevention is better than cure. But as long as people are getting infected, we need new antiviral agents. And the only way to find them is by research on virus structure and function.

Note: Virology has two uses of the word “latent.” A virus such as herpes may persist within the host cell in a “latent state” (“latency”)—that is, its genome is present but inactive until a molecular signal reactivates viral replication. In a different sense, the “latent period” of infection by a virus refers to the time during which the virus is multiplying within a host but virus particles are not yet released.

Note: Virology has two uses of the word “latent.” A virus such as herpes may persist within the host cell in a “latent state” (“latency”)—that is, its genome is present but inactive until a molecular signal reactivates viral replication. In a different sense, the “latent period” of infection by a virus refers to the time during which the virus is multiplying within a host but virus particles are not yet released.

The key determinant of viral infection is its genome (Table 12.1). Viruses of the same genome type (such as double-stranded DNA) are more likely to share ancestry with each other than with viruses of a different type of genome (such as RNA). The classification model based on genome type was devised by David Baltimore, who, with Renato Dulbecco and Howard Temin, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1975 for discovering how tumor viruses cause cancer.

Viral genomes are more diverse in composition than the genomes of cells, which are always made up of double-stranded DNA. A viral genome is composed of either DNA or RNA, depending on the viral species, and in different species the genome may be double-stranded or single-stranded. As mentioned earlier, each viral genome (DNA or RNA) is enclosed within a protein coat, the capsid. The capsid keeps the viral genome intact outside the host. In some species, the capsid is further encased by an envelope formed out of host phospholipid membranes with embedded viral envelope proteins. The capsid (and envelope, if present) must provide a mechanism of infection for the next host cell. The infection mechanism must be one of two types: (1) injection of viral genome into the host cell or (2) uptake of the virus into the host cell, followed by disassembly, or uncoating. In either case, the original virion loses its own structure and its own identity as such. Loss of individual identity is necessary for the virus to generate progeny virions.

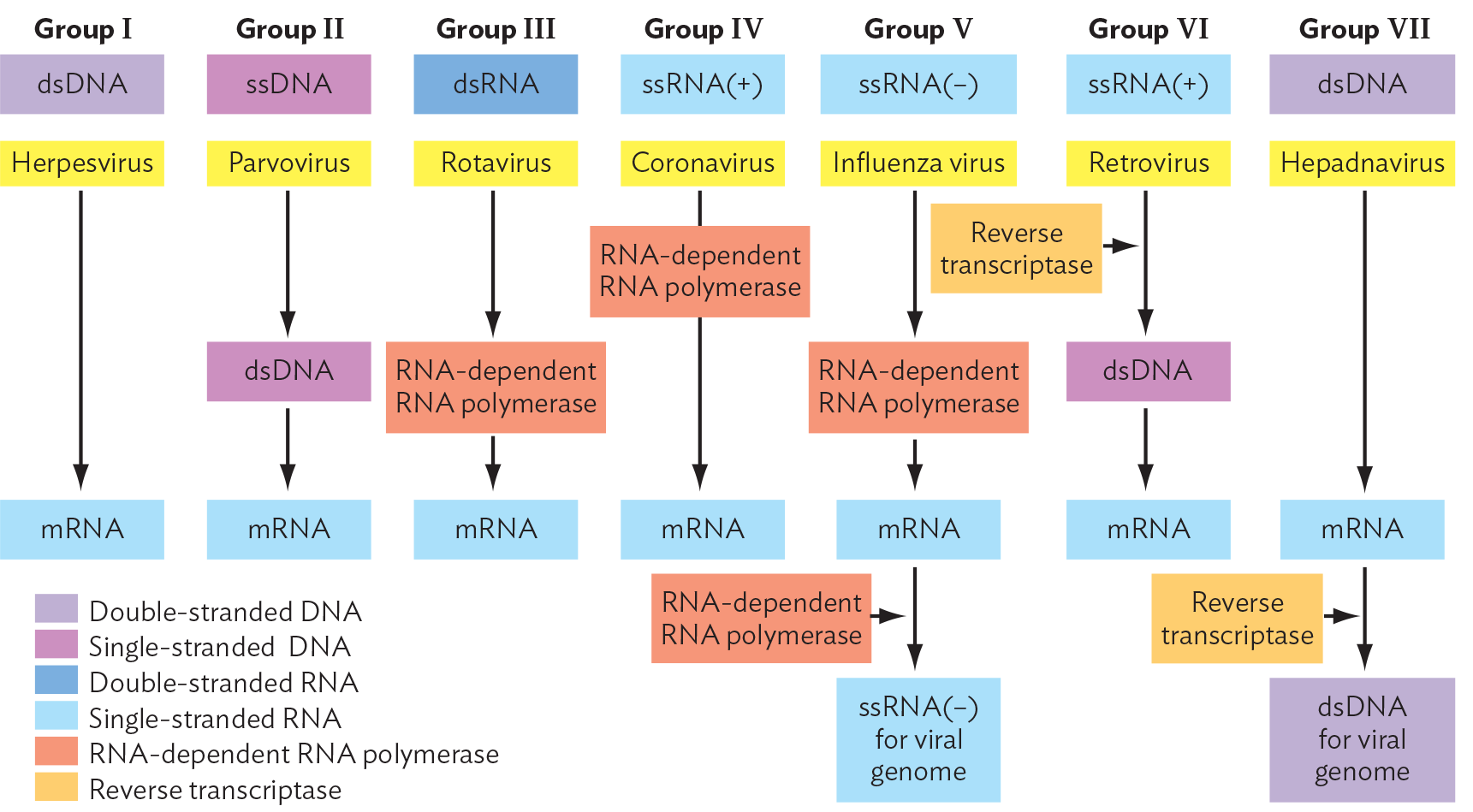

The Baltimore model classification of viral groups is based on whether the genome is composed of RNA or DNA; whether it is single- or double-stranded; and, if single-stranded, whether the strand directly encodes proteins or requires synthesis of a complement that encodes proteins (Figure 12.3). The type of genome determines how the virus will manufacture progeny virions. For example, an RNA virus such as coronavirus or influenza virus lacks DNA and therefore cannot use a cellular DNA polymerase to replicate its genes; the virus must encode an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Assuming a common host, the different means of mRNA production generate distinct groups of viruses with shared ancestry.

A diagram of the Baltimore Classification of Viral Genomes. Text reads, there are seven categories of viral genomes, which consist of R N A or D N A and are either single stranded, abbreviated s s, or double stranded, abbreviated d s, and either positive or negative sense. Each kind of genome requires a different route to m R N A and a different replication mechanism. End text. Group 1 is double-stranded D N A. Herpesvirus is a member of this group. D s D N A is converted directly into m R N A through transcription. Group 2 is single stranded D N A. Parvovirus is a member of this group. S s D N A is first converted to double stranded D N A and then transcribed into m R N A. Group 3 is double stranded R N A. Rotavirus is a member of this group. The conversion of d s R N A into m R N A is facilitated by R N A dependent R N A polymerase. Group 4 is positive sense single stranded R N A. Coronavirus is a member of this group. The conversion of positive sense s s R N A into m R N A is facilitated by R N A dependent R N A polymerase. Group 5 is negative sense single stranded R N A. Influenza virus is a member of this group. The conversion of negative sense s s R N A into m R N A is facilitated by R N A dependent R N A polymerase. The R N A dependent R N A polymerase is required again for the conversion of m R N A back into negative sense s s R N A for the packing of the viral genome into virions. Group 6 is positive sense single stranded R N A. Retrovirus is a member of this group. The s s R N A is first converted into double stranded D N A via reverse transcriptase. Then, the d s D N A is converted into m R N A through transcription. Group 7 is double stranded D N A. Hepadnavirus is a member of this group. The d s D N A is converted directly into m R N A. Reverse transcriptase then facilitates the conversion of m R N A back into d s D N A for the packaging of the viral genome into virions.

The seven Baltimore groups of viruses, based on genome type and mRNA generation, are outlined in Figure 12.3. Examples of each group are presented in Table 12.1. Note, however, that within each genome type, very different viruses have evolved in hosts as different as humans and bacteria. It is likely that a given form of genome (such as single-stranded DNA) evolved independently in different viral lineages.

The type of genome (DNA versus RNA, single- versus double-stranded) determines how the virus infects the cell and can influence the course of disease in the patient. Double-stranded DNA viruses (group I), such as herpesviruses and poxviruses (poxviruses cause smallpox and cowpox), make their own DNA polymerase or use that of the host for genome replication. Their genes can be transcribed directly by a host RNA polymerase. An exception is the poxviruses, which replicate in the cytoplasm and encode their own RNA polymerase to make mRNA.

By contrast, single-stranded DNA viruses (group II), such as canine parvovirus, require the host DNA polymerase to generate the complementary DNA strand. The double-stranded DNA is then transcribed by host RNA polymerase to make mRNA.

Double-stranded RNA viruses (group III) require a viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase to generate mRNA by transcribing directly from the RNA genome. An example is rotavirus, which causes diarrhea in children. Such viruses must package a viral RNA polymerase with their genome before exiting the host cell.

Single-stranded RNA viruses, such as hepatitis C virus and SARS coronavirus (group IV), have a positive-sense (+) strand (the coding strand) that can serve directly as mRNA to be translated to viral proteins. They then make an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase to synthesize a template (−) strand complementary to the (+) strand. The (+) strand for progeny virions is then replicated from the (−) template.

Other RNA viruses, such as influenza virus, actually package the complementary sequence of RNA, the (−) strand, instead of the coding strand. With their (−) RNA, these viruses (group V) must also package a viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase for transcribing (−) RNA to (+) mRNA, which is translated by ribosomes. Later, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase uses the (+) RNA to synthesize genomic (−) RNA. The (−) RNA genomes are then packaged into progeny virions.

A special case is the retroviruses, or RNA reverse-transcribing viruses (group VI). The retroviruses, such as HIV and feline leukemia virus, have genomes that consist of (+) strand RNA. They package a reverse transcriptase, which transcribes the RNA into a double-stranded DNA (see Section 12.6). Another kind of retrovirus (group VII) actually consists of DNA but replicates via an RNA intermediate. An example is hepatitis B virus (a hepadnavirus), which infects the liver.

Note: In nomenclature, families of viruses are designated by Latin names with the suffix “-viridae”—for example, “Papillomaviridae.” Common forms of such family names are also used—for example, “papillomaviruses.” Within a family, a virus species is simply capitalized, as in “Papillomavirus.”

Note: In nomenclature, families of viruses are designated by Latin names with the suffix “-viridae”—for example, “Papillomaviridae.” Common forms of such family names are also used—for example, “papillomaviruses.” Within a family, a virus species is simply capitalized, as in “Papillomavirus.”

SECTION SUMMARY

Thought Question 12.1 Why are relatively few antiviral agents available, compared with antibiotics? And why are the side effects of antivirals more harmful?

Antibiotics are molecules that specifically attack bacteria, not human cells. Antiviral agents, however, must inhibit virus production within an infected host cell. Because virus production involves host components, antiviral agents may harm host cells, including cells uninfected by virus. It’s hard to find an antiviral agent that successfully blocks viruses without harming the host.