SECTION OBJECTIVES

- Describe the genome of papillomavirus.

- Outline the replication cycle of papillomavirus.

- Explain how papillomavirus causes cancer.

SECTION OBJECTIVES

CASE HISTORY 12.1

Genital Warts from a Virus

A digital model of a human papilloma virus particle. The particle is roughly spherical. Its outer surface is covered in proteins. They form a lattice type pattern.

A photo of genital warts, a symptom of certain strains of human papillomavirus infection. There is a penis with several darkly colored, raised patches of skin. The raised areas appear bumpy and wrinkled. The surrounding skin is smooth and light in color for comparison.

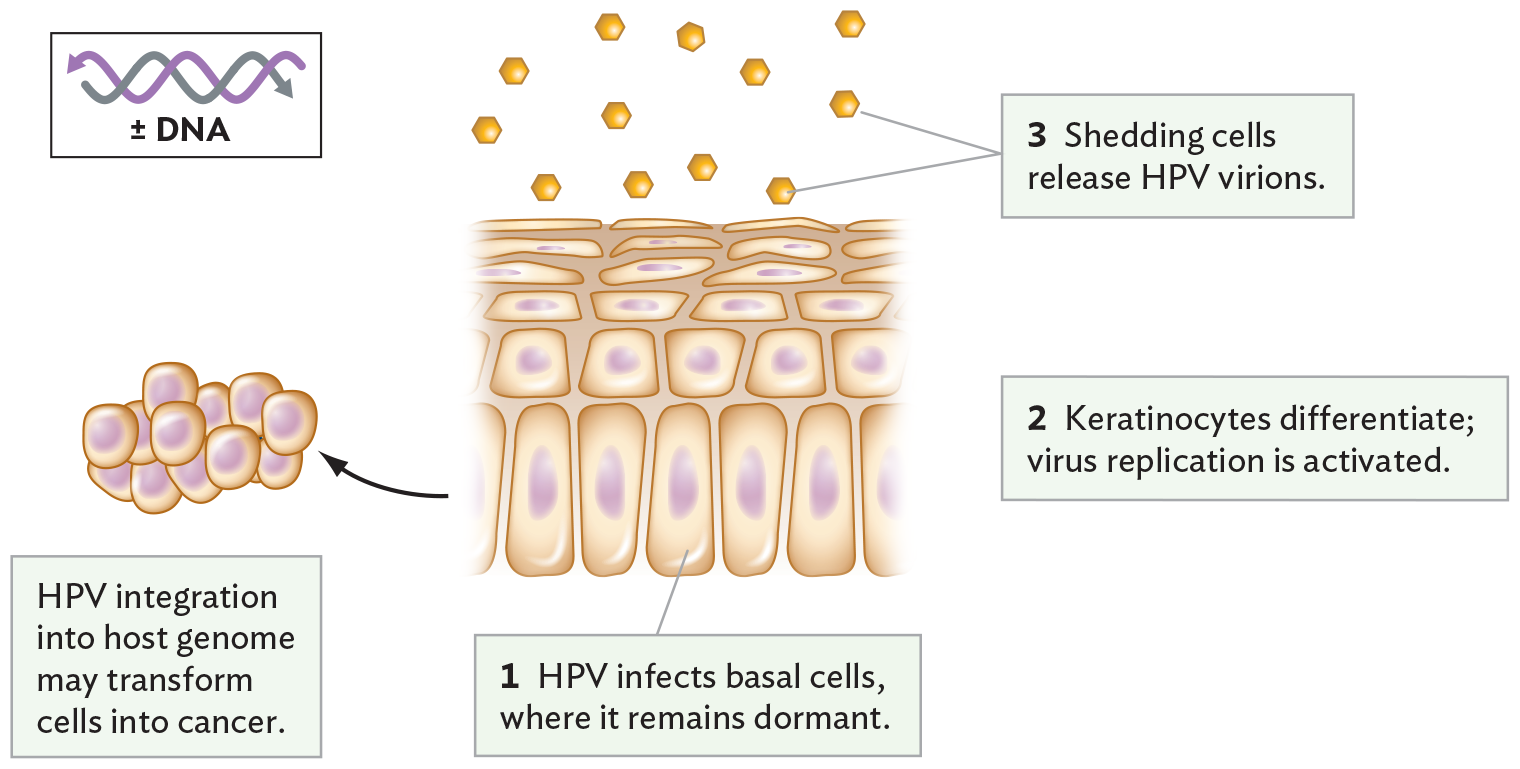

A diagram of human papilloma virus infecting basal epithelial cells. There is an illustration of the cell layers in skin. Tall, basal epithelial cells form the bottom layer. The cells in the layers above become smaller and elongated horizontally the closer they are to the skin surface. H P V infects the basal cells, where it remains dormant. The keratinocytes differentiate and virus replication is activated. At the surface of the skin, shedding cells release H P V virions. It is noted that H P V integration into the host genome may transform the basal epithelial cells into cancer. There is an illustration of a clump of irregularly shaped cells, demonstrating early tumor development. The H P V genome consists of double stranded D N A.

How prevalent is papillomavirus? In the United States, the genital strains of human papillomavirus (HPV), including those that cause cancers of the cervix, penis, and anus, infect 80% of adults. The discovery that cervical cancer is caused by HPV earned German researcher Harald zur Hausen the 2008 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (he shared the prize with Françoise Barré-Sinoussi and Luc Montagnier, the researchers who discovered that HIV causes AIDS; see Section 12.6). The genital strains of HPV are highly infectious through sexual contact, including oral contact leading to throat cancers. Although condoms offer partial protection, greater protection is afforded by vaccines such as Gardasil; however, the vaccine is effective only before exposure to the virus. Gardasil is now recommended by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for all children by age 11–12, or up to age 26 for those not vaccinated sooner. The vaccine protects against four of the most prevalent strains, including HPV-16, the leading cause of genital cancer and throat cancer. The only sure way to avoid genital HPV, however, is to abstain from sexual contact or to have sex only in a mutually monogamous relationship where you know the HPV status of your partner.

Like many viruses, HPV shows tropism, the ability to infect only specific organs or tissues. HPV has a narrow tropism: strains infect specifically the skin (cutaneous epithelium; Figure 12.16B) or the mucous membranes such as oral or genital mucosa. Tropism is usually determined by specific cell-surface protein receptors (just as bacteriophage attachment requires specific host protein receptors). For HPV, the receptors for some strains are heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs), cell-surface proteins involved in wound healing. The cell needs these proteins for important functions, and HPV evolved to take advantage of them.

In the affected tissues, the virus must gain access to the actively dividing cells of the basal layer, usually through a tiny wound in the tissue. Virions are endocytosed by the basal cells. Their replication, however, is inhibited until the basal cells start to differentiate into keratinocytes (mature epithelial cells). As the epithelial layers reach the surface and slough off, progeny virions are shed. In other infected cells, however, the HPV virions become latent, persisting in the cell for months or years. These latent viral genomes may induce the host cells to form abnormal growths, such as warts or cancers. Different HPV strains cause skin warts, genital warts, and genital cancers; that is why, in Case History 12.1, Sean was told that the penile warts would not cause cancer but similarly transmitted HPV strains could.

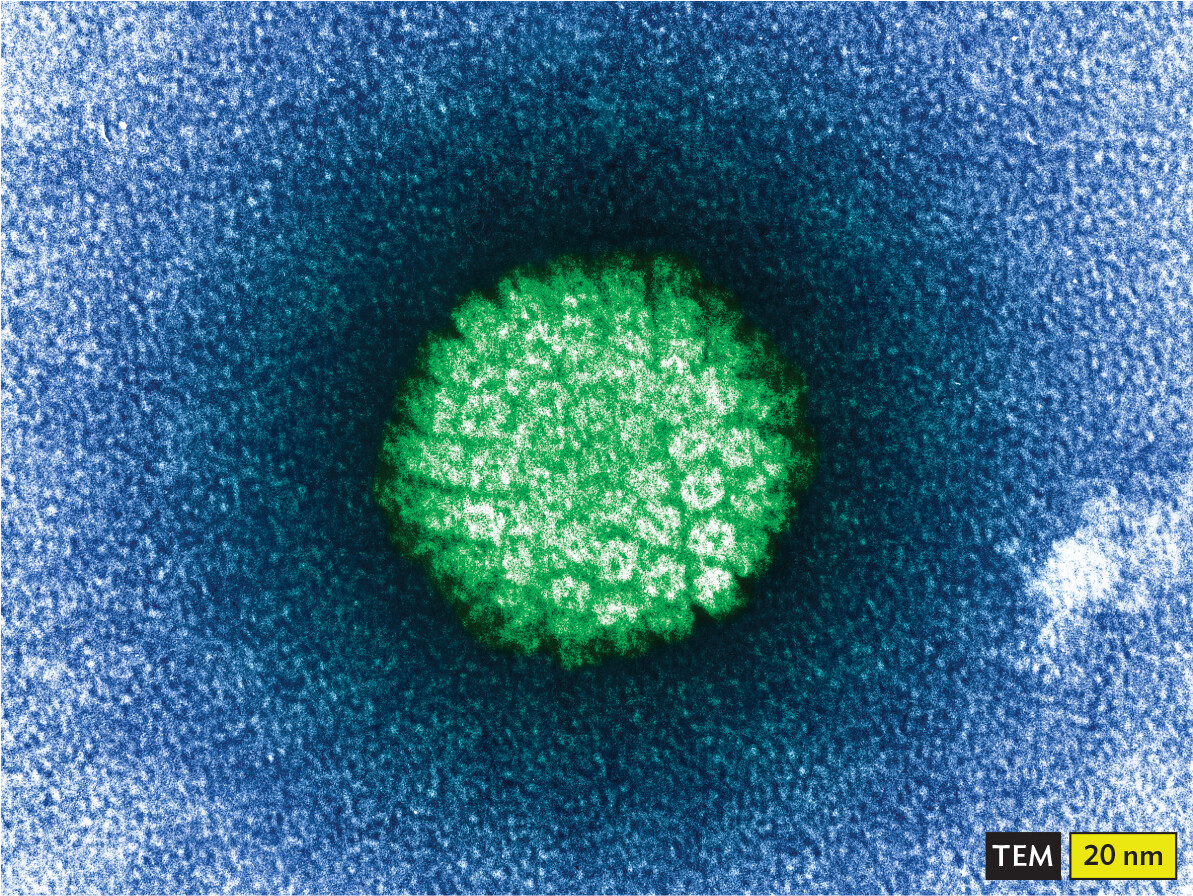

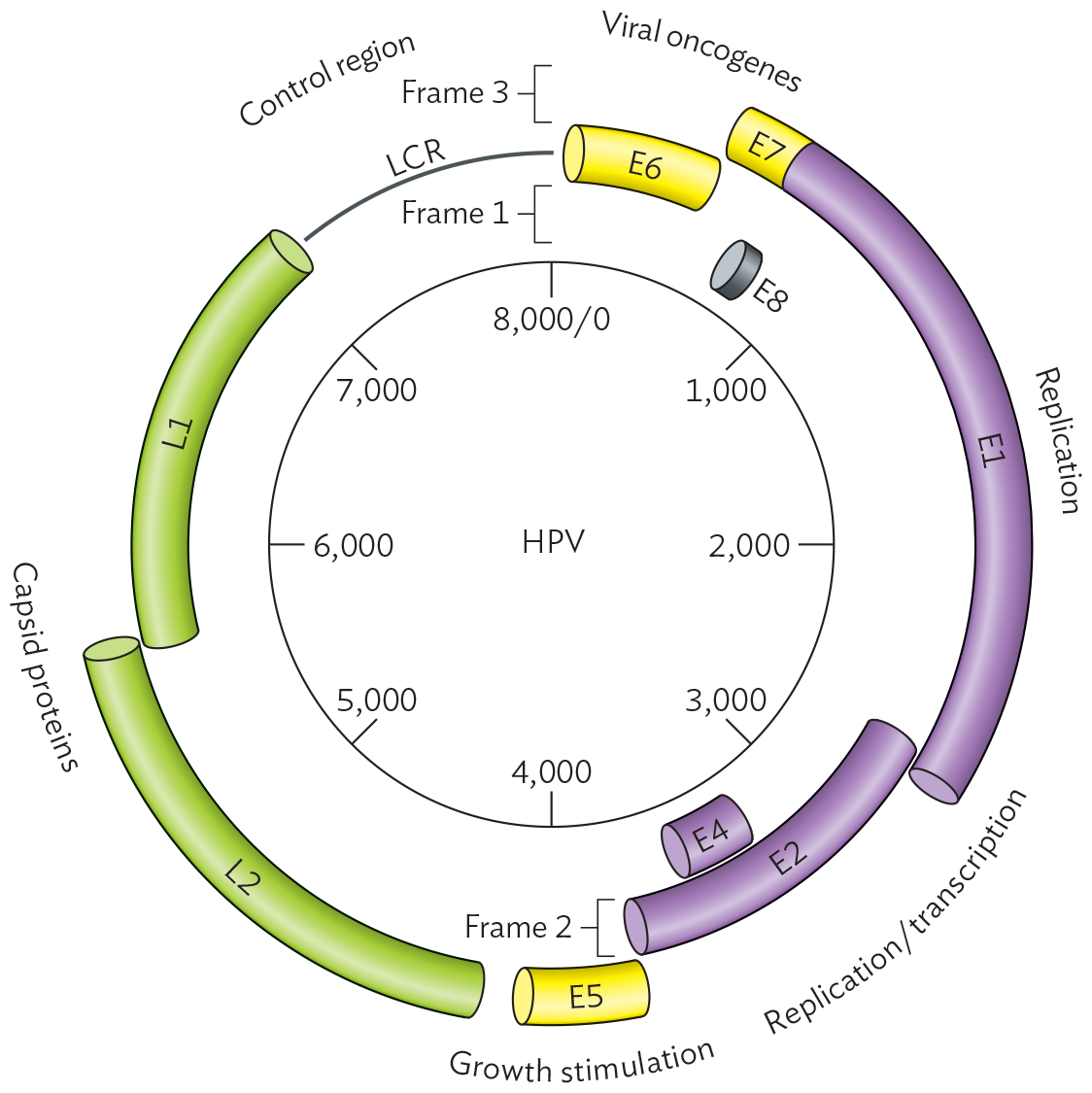

Structurally, the papillomaviruses are small icosahedral viruses, about twice the size of a ribosome. The virion has no envelope (Figure 12.17A). Its genome consists of a circular, double-stranded DNA (Baltimore Group I; see Table 12.1). The papillomavirus genome is relatively small, compared with the genomes of herpesvirus or mimivirus; for example, HPV-16 has fewer than 8,000 base pairs, encoding only eight gene products (Figure 12.17B). The genes are expressed in overlapping reading frames. Reading frames represent the three different ways that an RNA sequence can be read to define triplet codons (presented in Chapter 8). Using three reading frames allows partial overlap of the genes and maximizes the efficiency of the information content in the shortest possible genome. The shorter the viral genome, the faster the virus can copy itself—and the greater the number of virions that can be made with the DNA nucleotides available within a host cell.

A transmission electron micrograph of an H P V virion. The micrograph shows a roughly spherical particle. Its outline is fuzzy and its surface is covered in peg shaped proteins. It has a diameter of about 70 nanometers.

A schematic of the genome of HPV-16. The genome is displayed in a circle. The circle is eight thousand base pairs in circumference, with markings noting every one thousand bases. Tubes spanning between these markings show different genes that are broken into three rings representing frames 1, 2 and 3. The first frame shows a short E 8 gene slightly before one thousand and small curved tube labeled E 4 between three thousand and four thousand. The second frame shows the long curved tube E 2 between two thousand and four thousand, long curved tube L 1 between five thousand and eight thousand, and small curved tube E 6 between zero and one thousand. The second frame also shows the L C R, or long control region, between segments L 1 and E 6. The third frame shows the long curved tube with two sections E 7 and E 1 between 500 and three thousand. The small curved tube E 5 is located around four thousand. The long tube L 2 is from four thousand to six thousand. Viral oncogenes are found between bases 0 and one thousand. Replication genes are between bases one thousand to three thousand. Replication and transcription genes are between bases three thousand to three thousand seven hundred. Growth stimulation genes are around four thousand. Capsid protein genes are between bases four thousand to seven thousand.

Because HPV replication requires the developmental transition of basal cells into cells of the epidermis (outer skin layers; see Figure 12.16B), the virus is difficult to grow in culture for study. HPV is often eliminated by the host immune system, but if infection persists, no effective drug therapies are known. To discover treatments for HPV, researchers must identify drug targets by studying the virus’s replication cycle.

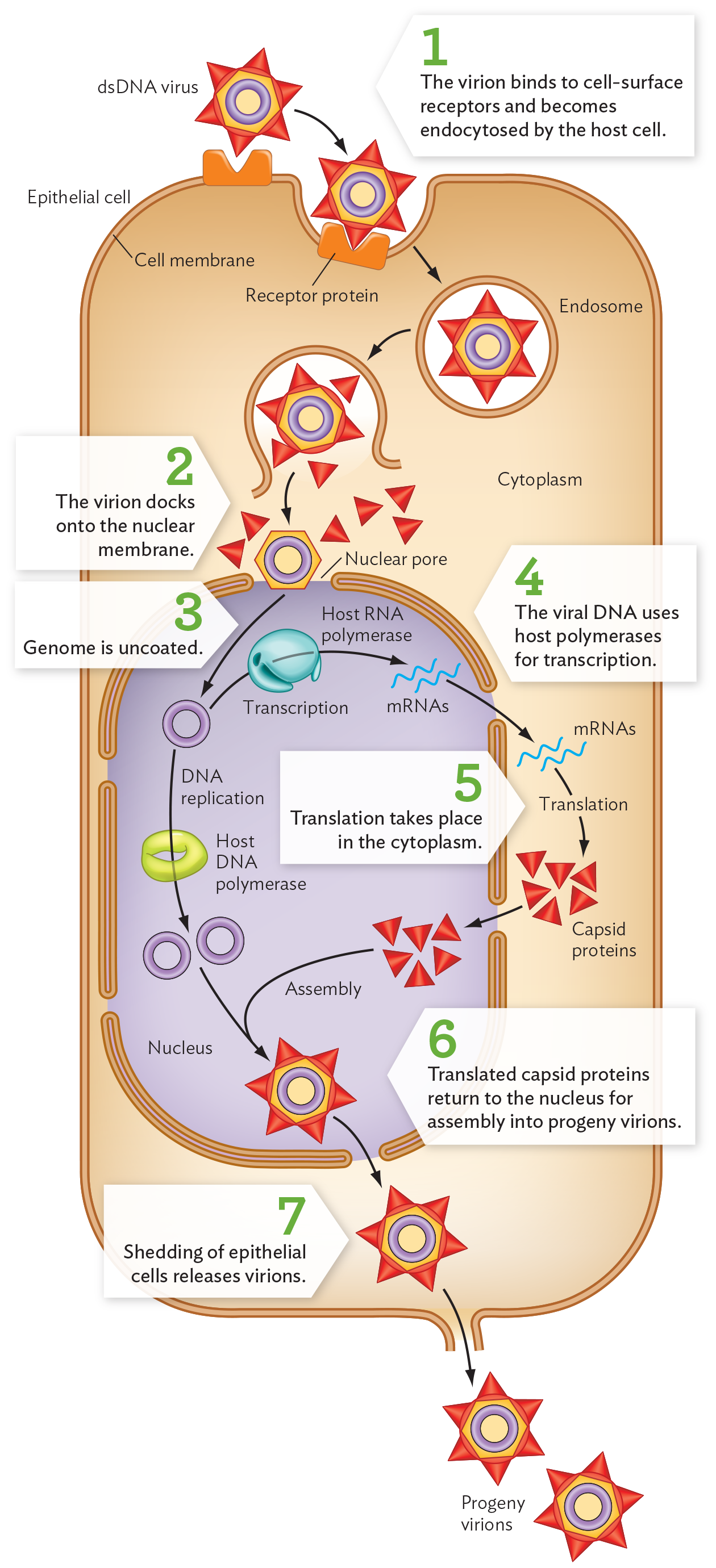

To infect a host cell and initiate replication, the HPV virion binds to cell-surface receptors (such as the heparan wound-healing proteins). The bound virion then becomes endocytosed by the host cell (Figure 12.18, step 1). The virion then travels through the endomembrane system (described in Chapter 5). To dock at a nuclear pore complex (step 2), the virus uncoats; that is, the capsid releases its genome (step 3). For HPV, the uncoated genome must enter the nucleus for all replication events. Nuclear replication is typical of many DNA viruses (such as herpes), but other DNA viruses, such as smallpox and mimiviruses, replicate entirely in the cytoplasm.

A diagram of the papillomavirus replication cycle. There is a large rectangular box-shaped structure, identified as an epithelial cell, with a thick cell membrane. The nucleus is located in the lower portion of the cell. Nuclear pores form gaps in the nuclear membrane. The double-stranded D N A papilloma virus is shown as a hexagon-shaped particle with a central ring structure. The outer surface of the particle is covered in triangular capsid proteins. A receptor protein on the epithelial surface provides a docking port that matches the shape of the triangular proteins. The virion binds to the cell surface receptor and becomes endocytosed by the host cell. It enters into the cytoplasm inside a circular ring-shaped structure, an endosome. The endosome breaks open and releases the virion into the host cell cytoplasm. The triangles break off and the hexagon-shaped structure alone reaches the nucleus. The virion docks onto the nuclear membrane. The circular viral genome is uncoated and enters the nucleus. D N A replication occurs using the host D N A polymerase. The ring-shaped structure of the virion D N A divides into two ring-shaped structures. The virion D N A is also transcribed by the host R N A polymerase to create strands of viral m R N A. Outside the nucleus the m R N A strands are transcribed into triangular capsid proteins. These proteins enter the nucleus for assembly into progeny virions. The triangle capsid proteins combine with the circular D N A to form a new d s D N A virus. The virion leaves the nucleus and the shedding of epithelial cells releases the virions. The progeny virions are now outside the cell.

For HPV, host cell differentiation induces the viral DNA to replicate and undergo transcription by host polymerases (Figure 12.18, step 4). The viral mRNA transcripts then exit the nuclear pores, as do host mRNAs, for translation in the cytoplasm to form capsid proteins (step 5). The capsid proteins, however, return to the nucleus for assembly of the virions (step 6).

As the keratinocytes complete differentiation, they start to come apart and are shed from the surface. The virions are released from the cell during this shedding process (Figure 12.18, step 7). In some cases, the virus is eventually eliminated by the body’s immune system. In the basal cells, however, HPV may take an alternative pathway, integrating its genome into that of the host basal cells (analogous to phage lysogeny, presented in Section 12.3). The integrated genome can transform host cells into cancer cells through increased expression of viral oncogenes (genes that cause cancer). The main oncogenes of HPV encode proteins E6 and E7 (see Figure 12.17B), which inhibit the expression of host tumor suppressor genes such as p53 and pRB.

Accordingly, different HPV strains exhibit two different viral strategies. Oncogenic HPV strains persist in the body for decades while producing low numbers of virions. Non-oncogenic strains, the kind that form warts, produce large numbers of progeny virions but can eventually be eliminated by the host immune system. These two strategies are also shown in the evolution of very different kinds of viruses.

A DNA virus may cause cancer by integrating its viral genome within a chromosome of the host cell in such a way as to disrupt host cell growth regulation. The process of a virus inducing carcinogenesis (change to cancer) in a host cell is called transformation. For a virus, the advantage of cancer transformation is that it expands the population of infected cells proliferating virus particles. If the viral genome is integrated into that of the host, the host now replicates the viral genome in a location invisible to the host immune system.

Some retroviruses (reverse-transcribing RNA viruses) cause a high rate of virulent cancer; these are called oncogenic viruses. An oncogenic virus usually carries an oncogene that disrupts the host cell growth cycle. For example, human T-lymphotrophic virus (HTLV), closely related to HIV, causes abnormal proliferation of the T cells that it infects. HTLV carries the tax oncogene, encoding a protein that stimulates cell growth despite contact inhibition (contact with neighboring cells that halts growth). The tax oncogene transforms normal cells into cancer cells.

Where do oncogenes come from, and how do they interact with host cells in such subtle ways? In some cases, a viral oncogene shows homology with a normal host cell gene called a proto-oncogene. A virus may acquire a host proto-oncogene and convert it to an oncogene whose uncontrolled expression causes uncontrolled cell proliferation.

Note: Distinguish between two uses of the term “transformation.” A cell can be transformed with DNA, meaning that the cell takes up exogenous DNA into its own genome. In a different sense, a cell can be transformed by a virus, converting to a cancer cell (oncogenesis).

Note: Distinguish between two uses of the term “transformation.” A cell can be transformed with DNA, meaning that the cell takes up exogenous DNA into its own genome. In a different sense, a cell can be transformed by a virus, converting to a cancer cell (oncogenesis).

SECTION SUMMARY

Thought Question 12.5 What are the advantages and disadvantages to the virus of replication by the host polymerase, compared with using a polymerase encoded by its own genome?

The advantage of genome replication by the host polymerase is that the virus does not need to encode a polymerase in its own genome, so its genome can be smaller. The advantage of the virus encoding its own polymerase is that the viral polymerase can be optimized for the needs of the virus; for example, the viral polymerase can be error prone, generating mutant progeny that escape the immune system. In addition, RNA viruses must encode their own polymerase because the host cells lack any polymerase that synthesizes RNA from an RNA template.