SECTION OBJECTIVES

- Explain how viral genomes enter cells.

- Describe the lytic and lysogenic cycles of bacteriophage infection.

- Explain how viruses are cultured using host cells.

SECTION OBJECTIVES

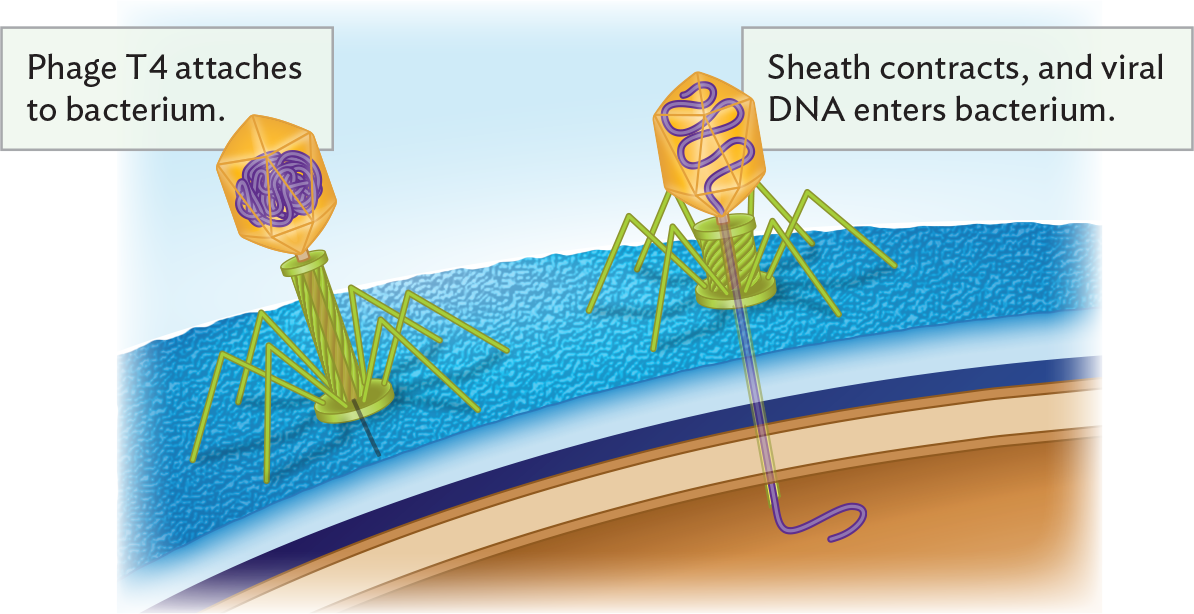

How does a bacteriophage find its host cell, subvert the host’s defenses, and take over its metabolism? Viruses show surprisingly diverse mechanisms for infection and replication. Each molecular step of infection offers a potential target for antiviral agents. In this section we examine bacteriophages that inject their DNA genome into the host bacterium (Figure 12.12). Subsequent sections present examples of human viruses with DNA and RNA genomes.

An illustration of the method of bacteriophage genome insertion into a bacterium. The illustration is focused on an enlarged view of the outer surface of a bacterium. Phage T 4 attaches to the bacterium by its base plate. Phage T 4 consists of an icosahedral head structure that contains the double stranded D N A genome attached to a cylindrical tail structure. The base plate is at the bottom of the tail. Supportive tail fibers extend from the base plate in inverted V shapes, stabilizing the phage on the bacterium. Once the phage is stable, the sheath contracts and viral D N A enters the bacterium. The tightly packed genome moves through the tail structure into the bacterial cell.

One way or another, all viral replication cycles must achieve the following tasks:

A virus needs to contact and attach to the surface of an appropriate host cell, one that its own genetics has evolved to take over. A virus binds specifically to a surface receptor, a protein on the host cell surface that is specific to the host species and that binds to a specific viral part. An example is the tail fibers of bacteriophage T4, which bind to the bacterial cell-surface lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Figure 12.12).

Why would a host cell evolve to make a surface protein that attaches to a virus? In fact, the receptor for a virus is a protein with an important function for the host cell, but the virus has evolved to take advantage of the protein. For example, the CD4 surface protein of T cells (see Chapter 16) is often called an “HIV receptor,” although it evolved as a signaling protein of the immune system.

Bacteriophages interact with bacteria in all ecosystems, from soil and water to the human gut. Phages decrease population density, increase host diversity, and transfer genes among diverse bacteria. Phages are relatively easy to study in the laboratory, where their host bacteria can be grown in tube and plate cultures (methods are presented in Chapter 6). Thus, phage-host systems provide important models for human virus infection and for virus culture.

We present here the extensively studied bacteriophage lambda, which infects the common enteric bacterium Escherichia coli. Enteric bacteriophages are an important part of the ecology of the human intestine, where they transfer genes between bacteria by transduction (see Section 9.1).

How does bacteriophage lambda know which bacteria to infect within the mixed population of our colon? The phage virion binds specifically to the maltose porin in the outer membrane of E. coli. Although the maltose porin protein is often called “lambda receptor protein,” it actually evolved in E. coli as a way to obtain the sugar maltose for food. Thus, natural selection maintains the maltose porin in E. coli, despite the danger of phage infection.

So how does the inert phage particle penetrate the castle-like fortress of the bacterial cell? The phage injects its genome through the cell envelope into the cytoplasm, thus avoiding the need for the capsid to penetrate the tough cell wall. The sheath of the phage neck tube contracts, bringing the head near the cell surface to insert its DNA (see Figure 12.12). The pressure of the spooled DNA—as high as 50 atmospheres—is released, expelling the DNA into the cell. After inserting its genome, the phage capsid remains outside, attached to the cell surface. The empty capsid is termed a “ghost” because of its pale appearance in an electron micrograph. (In contrast, animal viruses enter their hosts by binding to receptors that trigger endocytosis or fusion with the host cell membrane, to be discussed shortly.)

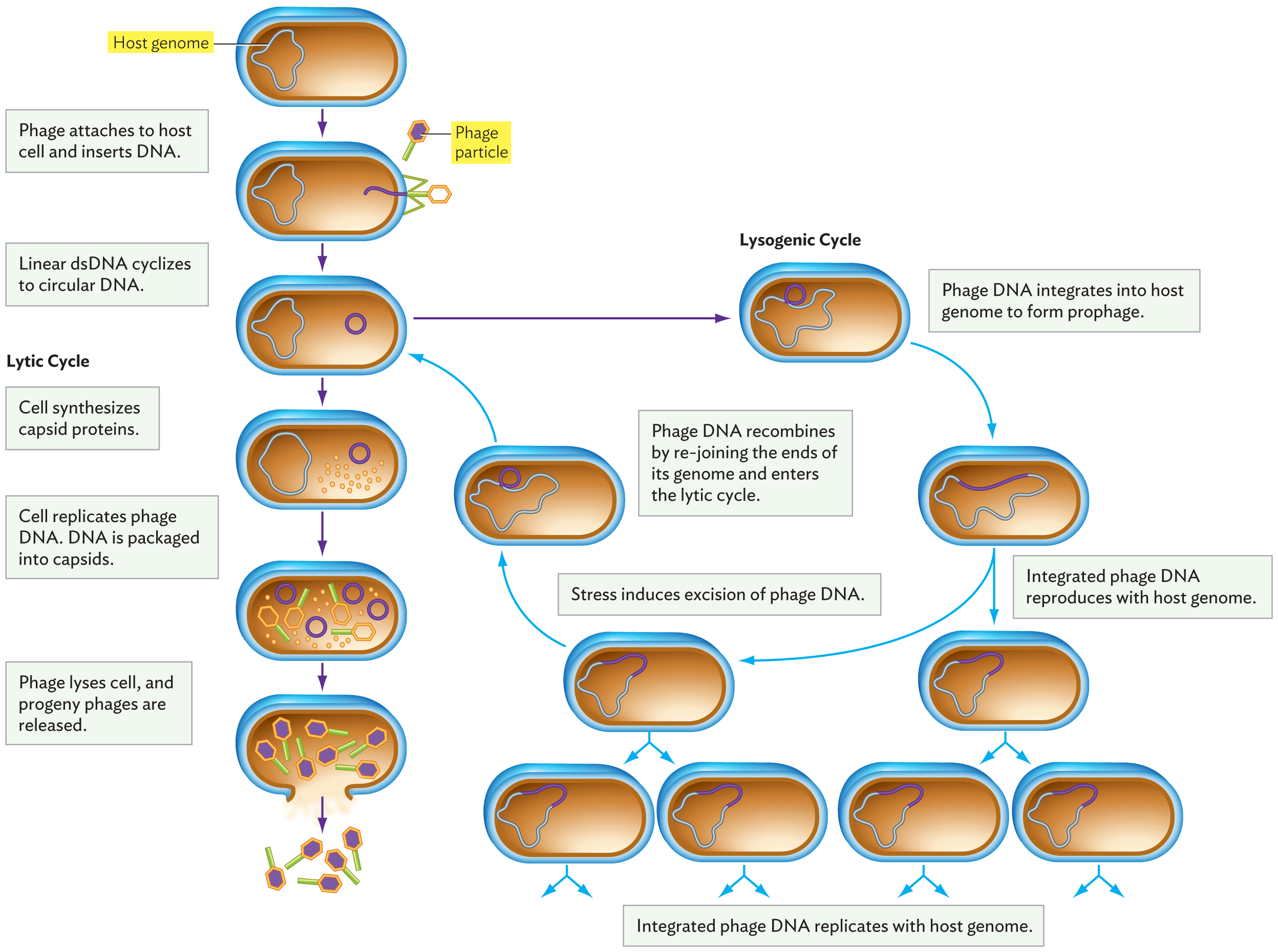

When a virulent phage injects its genome into a cell, it immediately begins a replication cycle to form as many progeny phage particles as possible (Figure 12.13A). The process involves replicating the phage genome and then expressing phage mRNA to make enzymes and capsid proteins. Ultimately, the phage particles assemble, and lysis (rupture of the host cell) follows, releasing progeny phages (lytic infection). Some phages, such as phage T4, digest the host DNA to increase the efficiency of phage production; others, such as phage lambda, retain the host DNA for potential lysogeny. Lysogeny is a process in which the phage genome becomes integrated in the genome of the host cell (Figure 12.13B). Lysogenic phages may carry toxin genes, such as the gene that expresses Shiga toxin in E. coli O157:H7.

Two connected diagrams of lysis and lysogeny occurring within a cell as a result of phage activity. A pill shaped cell has a wavy thread-like loop inside which is the host genome. In the next step, a phage attaches to the host cell and inserts D N A. Linear d s D N A cyclizes to circular D N A. The phage D N A is now a circle in the host cell. From here, either the lytic cycle or the lysogenic cycle can occur. In the lytic cycle, the cell synthesizes capsid proteins. The cell then replicates phage D N A and the D N A is packaged into capsids. The phage then lyses the cell and the progeny phages are released. In the lysogenic cycle, The phage genome integrates into the host genome to form prophage. There is now only one large loop of D N A that is made of both phage and host D N A. The integrated phage D N A reproduces with the host genome. The host cell replicates several times creating four identical cells with the integrated D N A. Stress induces the excision of phage D N A. The phage D N A recombines by rejoining the ends of its genome and enters the lytic cycle.

A. Lysis occurs when the phage genome reproduces progeny phage particles—as many as possible—and then ruptures the cell to release them.

B. Lysogeny occurs when the phage genome integrates itself into the host’s genome. The phage genome is replicated along with that of the host cell. The phage DNA, however, can direct its own excision. This excised phage genome then initiates a lytic cycle.

We now examine in more detail the alternative “fates” of these two methods of phage replication: lytic infection (lysis) and lysogeny. Although we focus on bacteriophages, similar alternative strategies for replication—for example, rapid virus replication versus hiding in a host cell—are exploited by human viruses such as HIV and herpesviruses.

Lytic infection. Phage lambda has a linear genome of double-stranded DNA, which circularizes upon entry into the cell. The phage genes are expressed by the host cell RNA polymerase and ribosomes. “Early genes” are those expressed early in the lytic cycle—those needed for transcribing DNA and other early steps to produce progeny phages. Other phage-expressed proteins then work together with the host’s cellular enzymes and ribosomes to replicate the phage genome and produce phage capsid proteins. The capsid proteins self-assemble into capsids and package the phage genomes—a process that takes place in defined stages, like a factory assembly line. Finally, a “late gene” from the phage genome expresses an enzyme that lyses the host cell wall, releasing the mature virions. Lysis is also referred to as a burst, and the number of virus particles released is called the burst size.

Some other kinds of phages (such as phage T4) reproduce entirely by the lytic cycle and thus are called virulent phages. Phages that can undergo lysogeny, such as phage lambda, are called temperate phages. A temperate phage such as phage lambda can infect and lyse cells in the same manner as a virulent phage. A temperate phage can also exploit the alternative pathway, lysogeny, which involves integrating its genome into that of the host cell.

Lysogeny. To lysogenize, the circularized genome of lambda phage recombines into the host genome by site-specific recombination of DNA. In site-specific recombination, an enzyme aligns the phage genome with the host DNA and exchanges the sugar-phosphate backbone links with those of the host genome. The DNA exchange process integrates the phage genome into that of the host. The integrated phage genome is called a prophage. A similar integration event occurs in human viruses, such as when the DNA copy of an HIV genome integrates into the genome of a host T cell (see Section 12.6).

Integration of the phage lambda genome as a prophage results in lysogeny, a condition in which the phage genome is replicated along with that of the host cell as the host reproduces. However, the prophage retains the ability to spontaneously generate a lytic burst of phage. For lysis to occur, the prophage (integrated phage genome) directs its own excision from the host genome. The two ends of the phage genome are cut, come apart from the host DNA molecule, and then are re-joined so that the phage DNA is once again circularized. The phage DNA then initiates a lytic cycle, destroying the host cell and releasing phage particles.

For a temperate phage (a phage capable of lysogeny), the “decision” between lysogeny and lysis is determined by proteins that bind DNA and repress the transcription of genes for phage replication. Exit from lysogeny into lysis can occur at random, or it can be triggered by environmental stress such as UV light, which damages the cell’s DNA. The regulatory switch of lysogeny responds to environmental cues indicating the likelihood that the host cell will survive and continue to propagate the phage genome. When a cell grows under optimal conditions, it is more likely that the phage DNA will remain inactive, whereas events that threaten host survival will trigger a lytic burst. An analogous phenomenon occurs in human viral infections such as herpes, in which environmental stress triggers reactivation of a virus that was dormant within cells (a latent infection; this is different from phage lysogeny). Reactivation of a latent herpes infection results in painful outbreaks of skin lesions.

During the exit from bacteriophage lysogeny (or during the latent growth of animal viruses), a virus can acquire host genes and pass them on to other host cells. In bacteria, this process of viral transfer of host genes is known as transduction (discussed in Section 9.1). A transducing bacteriophage can pick up a bit of host genome and transfer it to a new host cell. In some forms of transduction, the entire phage genome is replaced by host DNA packaged in the phage capsid, resulting in a virus particle that transfers only host DNA. In other cases, only a small part of the host genome is transferred, attached to the viral genome.

The integration and excision of viral genomes make extraordinary contributions to the evolution of host genomes, including pathogens. For example, the CTXφ prophage encodes cholera toxin in Vibrio cholerae, and prophages encode toxins for Corynebacterium diphtheriae (diphtheria) and Clostridium botulinum (botulism). In the laboratory, the ability of phages to transfer genes is exploited in developing vectors (carrier genomes) for biotechnology.

To study any living microorganism, we must culture it in the laboratory. A complication of virus culture is the need to grow the virus within a host cell. So any virus culture system must be a double culture of host cells plus viruses.

Batch culture. Bacteriophages may be produced in batch culture, a culture in an enclosed vessel of liquid medium. Batch culture enables growth of a large population of viruses for study. A phage sample is inoculated into a growing culture of bacteria, usually in a culture tube or a flask. The culture fluid is then sampled over time and assayed for phage particles. The growth pattern usually takes the form of a one-step growth curve (Figure 12.14). To observe one cycle of phage reproduction, we must add phages to host cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI), the ratio of phage to cells, such that every host cell is infected. The phage particles immediately adsorb to surface receptors of host cells and inject their DNA. As a result, phages are virtually undetectable in the bacterial cell for a short period after infection called the eclipse period. The progeny phages within the bacterial cell before it lyses can be seen by transmission electron microcopy (see Figure 12.2A).

A line graph of the one step growth curve for a bacteriophage. The y axis displays phages per milliliter ranging from 0 to 10 superscript 5. The x-axis displays time in minutes ranging from 0 to 40. The number of phages remains at a low count for the first 10 minutes. After this point, the phage count rises rapidly, before leveling off at around 20 minutes. The first 12 minutes, when the phage count is less than 10 superscript 3, is called the eclipse period. The phage growth that occurs after is called the rise period. The rise period occurs between 12 to 20 minutes. During this period the phages per milliliter increases from almost zero to 10 superscript 5. Cell lysis is complete at 20 minutes. After this, the number of phages per milliliter stays constant for the rest of the time. An equation for burst size is written in the chart area. The burst size is calculated by dividing 10 superscript five phages per milliliter by 200 cells infected per milliliter. The result is a burst size of 500 phages per cell infected.

As cells begin to lyse and liberate progeny phages, the culture enters the rise period, in which phage particles begin appearing in the growth medium. The rise period ends when all the progeny phages have emerged from their host cells. The number of phages produced per infected host cell is called the burst size. We can estimate the burst size by dividing the concentration of progeny phages by the original concentration of the host cells, assuming that every phage particle infected a cell.

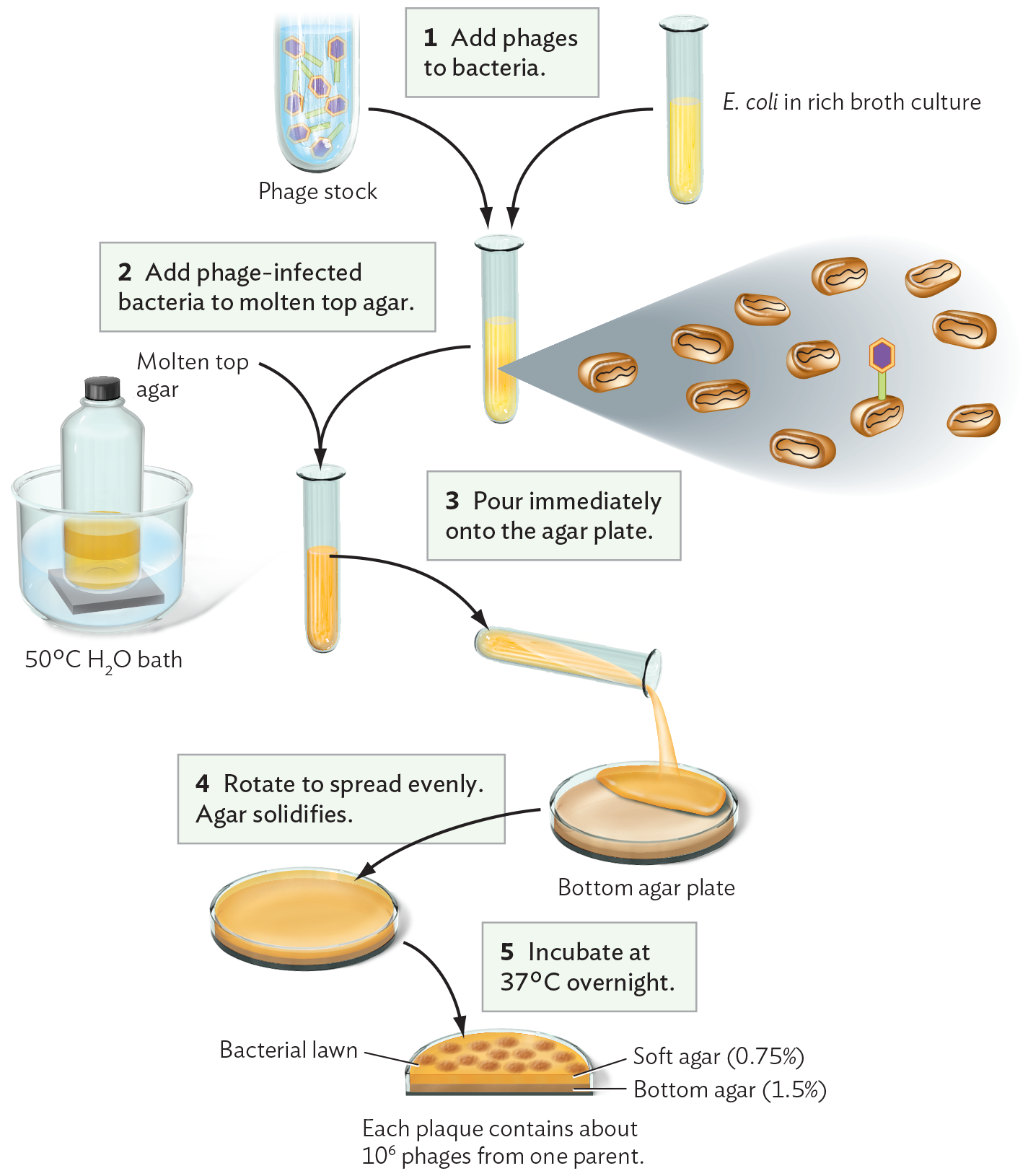

Plate culture. Another important culture technique is the growth of individual colonies on a solid substrate that prevents dispersal throughout the medium, as described in Chapters 1 and 6. Plate culture of colonies enables us to isolate a population of microbes descended from a common progenitor. But how can we isolate viruses as “colonies”? Although viruses can be obtained at incredibly high concentrations, they disperse in suspension. Even on a solid medium, viruses never form a solid visible mass comparable to the mass of cells that constitutes a cellular colony.

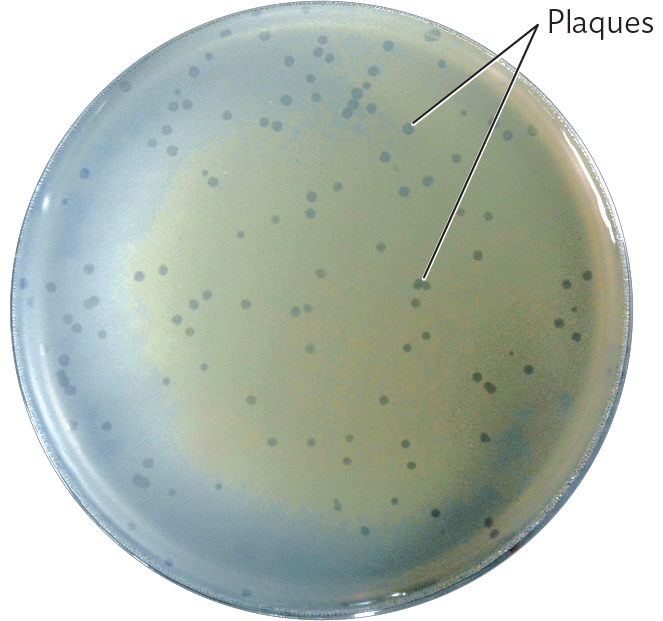

In bacteriophage plate culture (Figure 12.15), bacteriophages from a single progenitor lyse their surrounding host cells, forming a clear area called a plaque. To perform a plaque assay of bacteriophages, we mix a diluted suspension of bacteriophages with bacterial cells in soft agar (agar at low concentration) and then pour the mixture over an agar plate. Phage particles diffuse through the soft agar until they reach a host bacterium. Where no bacteriophages are present, the bacteria grow homogeneously as a “lawn,” an opaque sheet over the surface (confluent growth). Where there is a bacteriophage, it infects a cell, replicates, and spreads progeny phages to adjacent cells, killing them as well. The loss of cells results in a round, clear area seemingly cut out of the bacterial lawn; these tiny clear areas are the plaques. Plaques can be counted and used to calculate the concentration of phage particles, or plaque-forming units (PFUs), in a given suspension of liquid culture. The phage concentration can be measured by serial dilution in the same way we would measure a suspension of bacteria.

A diagram explaining the pour plate culture technique for a culture of bacteriophages added to a host bacterial lawn. There are two test tubes. One tube contains liquid phage stock and the other tube contains E. coli in rich broth culture. The phage stock and the E. coli are combined in a single test tube. Next, the phage infected bacteria are added to molten top agar. The molten top agar is prepared in a closed bottle warmed in a 50 degrees Celsius water bath. The mixture is poured immediately onto a sterile bottom agar plate and rotated to spread evenly. The agar solidifies. The agar plate is incubated at thirty seven degrees Celsius overnight. After the incubation, the agar has an opaque bacterial lawn. The lawn is disrupted by clear, circular plaques. Each plaque contains about 10 superscript 6 phages from one parent. It is noted that the upper area of the agar is soft agar, 0.75 percent, and the lower area is the original bottom agar, 1.5 percent.

A photo of an agar plate with phage lambda plaques on a lawn of E. coli K 12 bacteria. The agar plate is circular. The agar is covered with a thin grayish film, the lawn of E. coli K 12. Many clear circles are visible throughout the lawn where the film has been disrupted. These are phage lambda plaques.

The remaining three sections of this chapter describe the replication and pathology of viruses that infect humans: human papillomavirus (HPV), SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, influenza virus, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Each example reveals a different kind of replication cycle with very different implications for the patient.

SECTION SUMMARY

Thought Question 12.4 Given the mechanism by which viruses infect cells, how might an organism evolve to become resistant to a viral infection?

For viruses of animal cells, the crucial first step is for the virus to bind to a host cell surface. Surface binding requires a viral coat protein or spike protein to specifically recognize a receptor protein on the host cell membrane. But the host population may acquire a mutation in which the receptor protein is absent or has a changed peptide structure that no longer binds the viral spike protein. Mutation in the receptor gene can prevent infection by the virus.