SECTION OBJECTIVES

- Describe complex versus simple infection cycles.

- Differentiate between endemic, epidemic, and pandemic disease.

- Explain animal reservoirs and disease incubators.

SECTION OBJECTIVES

How are diseases spread? Somehow, pathogens must pass from one person, or nonhuman animal, to another, if a disease is to spread. The route of transmission an organism takes to infect additional hosts is called the infection cycle. These routes can be direct or roundabout, as seen in the case history presented next.

CASE HISTORY 2.1

A Hike, a Tick, and a Telltale Rash

An enlarged photo of a tick. The tick has a flattened ovoid body with a tiny spherical head. The tick is brown with darker brown streaks. Eight spindly legs extend from the tick body.

A photo of a hand with a rash related to Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. On lighter toned skin, the rash presents as a series of red and irritated spots across the skin surface.

An illustrated outline of a question mark overlaid on a scanning electron micrograph of Francisella tularensis. The cells are roughly spherical in shape. In this micrograph, the cells are colorized blue and the background environment is colorized yellow.

The Elegant Art of Diagnosing Infectious Disease

How Do Health Care Providers Determine What Ails You?

Suddenly you feel very ill. You don’t think it’s serious, but you go to the clinic, trusting that the clinician there will diagnose your illness and prescribe an effective treatment. How does the clinician make the right diagnosis? This book describes many infections that afflict humans and the pathogens that cause those diseases. Here we describe a skill that is critical for diagnosing disease and integral to every case history: the taking of a patient history.

When you go to the clinic, what is the first thing that happens when the physician, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner walks into the room? You are asked questions such as “What brings you here today?” or “How long have you had these symptoms?” and perhaps “Where have you traveled recently?” This is not idle conversation; the clinician is taking a patient history (Figure 1).

A photo of a doctor holding a clipboard and speaking to a patient. The patient is facing the doctor. The doctor has a serious expression on his face as he discusses something. The doctor is wearing a white lab coat over professional clothing. A stethoscope hangs down from his neck.

But what is a patient history, and why is it so important? Many infectious diseases display similar symptoms, making diagnosis of a specific disease difficult. However, the patient history provides critical clues that can guide the clinician to the possible culprit. For instance, Vibrio cholerae and enterotoxigenic E. coli both produce diarrheal diseases characterized by cramps, lethargy, and liters of watery stool each day. So, when a patient presents these symptoms, how does the clinician intuit which microbe is the cause in order to quickly begin treatment (even before seeing lab results)? Although cholera is not commonly seen in the United States, a clinician might suspect cholera if the patient recently traveled to or emigrated from an endemic area where the disease is regularly observed (India, for example). Of course, this travel information is not gained by examining the patient but comes from talking with the patient and taking a patient history.

A patient history, or medical history, is the written summary of a carefully choreographed dialogue between clinician and patient. It is composed of several parts:

Many questions asked while taking a patient’s social history can seem irrelevant or intrusive to the patient, who only wants relief from the symptoms. For instance:

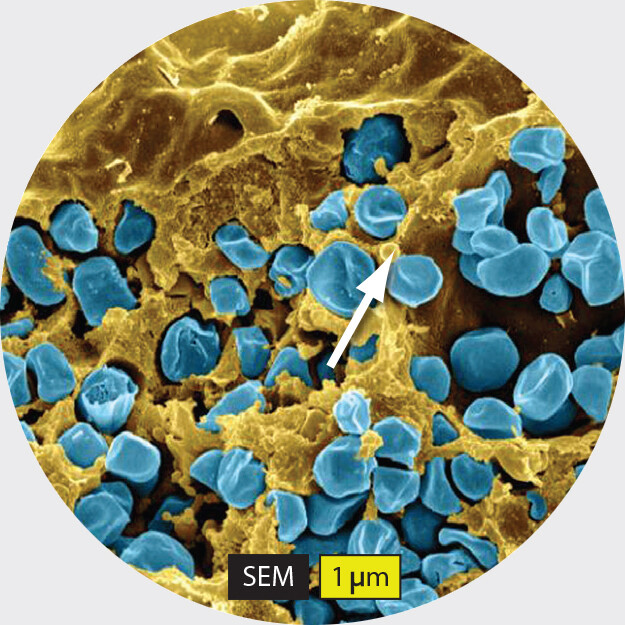

Although these questions may sometimes raise eyebrows, the answers can provide important diagnostic clues to the astute clinician. For example, learning that a man suffering from enlarged glands, fever, and headaches also likes to hunt and recently killed rabbits can be an important clue (Figure 2). The patient may have been exposed to the rod-shaped bacterium Francisella tularensis, a pathogen that infects various wild animals and is the cause of tularemia, an illness also known as “rabbit fever.” The patient could have accidentally infected a cut while cleaning his “kill.”

A photo of a severely swollen lymph node in the neck of a patient infected with tularemia. The lymph node has swollen to the size of a golf ball, noticeably protruding from the neck. The overlying skin is red and irritated against the patient’s lighter skin tone. A portion of the patient’s face can be seen. The individual appears to be grimacing in discomfort.

Or consider the case of a woman with acute pneumonia. The clinician discovers from taking a patient history that the woman is a sheep farmer. Knowing this, the clinician considers Coxiella burnetii as one of the possible causes of the infection (the list of possible causes is called the differential). C. burnetii is a pathogenic bacterial species that infects sheep and is shed in large quantities in the animal’s amniotic fluid or placenta. Dried soil contaminated with C. burnetii can become aerosolized (airborne) whenever the dirt is disturbed, and any human (such as a farmer) who inhales the dried particles can develop the lung infection Q fever. C. burnetii would be lower on the differential if the woman were an accountant.

A scanning electron micrograph of Francisella tularensis. A portion of a murine macrophage fills the background of the micrograph. The cell surface shown is covered in numerous depression within which F tularensis cells aggregate. The F tularensis cells are roughly spherical in shape. Pits and ridges give them a roughened exterior surface. Each F tularensis cell is about 0.75 micrometer in diameter. The caption reads, Francisella tularensis, A murine macrophage infected with Francisella tularensis strain L V S. The macrophage has been artificially colorized yellow and the F tularensis cells have been artificially colorized blue.

Keep the idea of patient history in mind as you read the numerous case histories to come. Take note of how often a patient history can tilt a diagnosis away from one suspected pathogen and toward another. In the end, you will have a greater understanding of infectious diseases and will be better able to appreciate the diagnostic skills required of a clinician.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever is caused by the bacterium Rickettsia rickettsii. Although initially recognized in the Rocky Mountain states, most cases of the disease occur on the East Coast. The organism lives in infected ticks without harming them. However, the bite of an infected tick can transmit the organism (present in tick salivary secretions) to unsuspecting humans and cause serious, life-threatening disease.

Note: This chapter is an introductory chapter. In-depth discussions of the infection cycles of specific organisms are presented in Chapters 19–24. Chapter 26 includes thorough coverage of epidemiology, including hospital- and community-acquired infections.

Note: This chapter is an introductory chapter. In-depth discussions of the infection cycles of specific organisms are presented in Chapters 19–24. Chapter 26 includes thorough coverage of epidemiology, including hospital- and community-acquired infections.

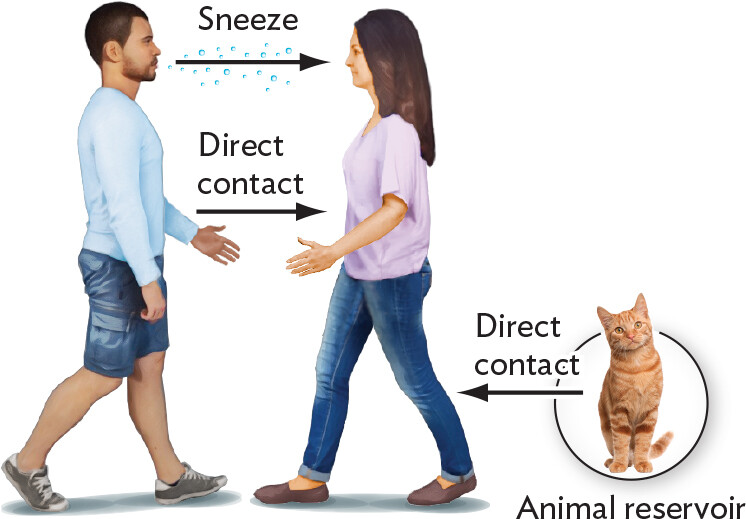

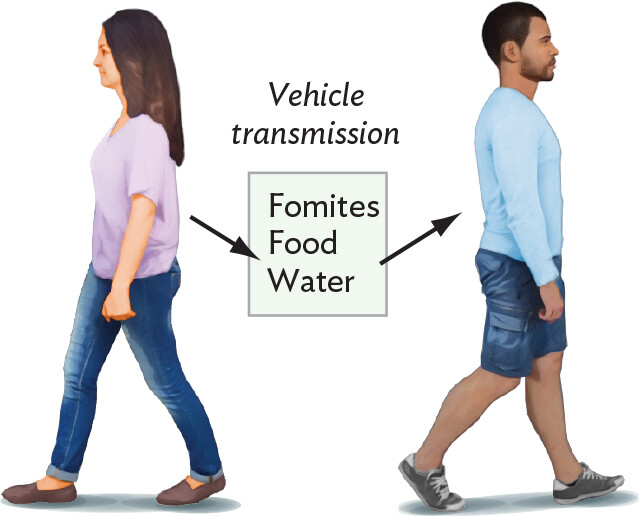

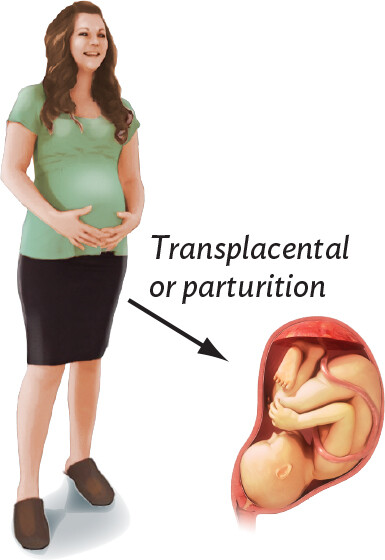

Often, a patient history helps uncover how the individual was infected in the first place—recall Emma Katherine’s tick bite. For an infectious disease to spread through a community, the pathogen must pass, or be transmitted, from one person or animal to another. The route of transmission is called an infection cycle (Figure 2.10). Terms used to describe infection cycles are provided in Table 2.2. The two major types of transmission are horizontal transmission, in which the infectious agent is transferred from one person or animal to the next (Figure 2.10A and B), and vertical transmission, whereby an infectious agent is transferred directly from parent to offspring (Figure 2.10C). One example of vertical transmission is provided by the cause of syphilis (Treponema pallidum), which can travel through the placenta to the fetus (transplacental transmission). In another example, the organism that causes gonorrhea (Neisseria gonorrhoeae) doesn’t pass through the placenta but can contaminate a newborn during birth (parturition; see Figure 2.10C). Both of these pathogens can be horizontally transmitted as well.

An illustration explaining direct horizontal transmission. An infected individual walks toward a noninfected individual. They reach out their hands to shake, which represents an opportunity for transmission through direct contact. The infected individual sneezes, sending droplets toward the noninfected individual. Inhalation of these droplets by the noninfected individual is another opportunity for transmission. Direct contact with an animal reservoir, such as a cat, represents another opportunity for transmission.

An illustration explaining indirect horizontal transmission. An infected individual interacts with inanimate objects, called fomites, food, or water. For certain pathogens, these items act as vehicles through which the pathogen can be transmitted to a noninfected individual.

An illustration explaining vertical transmission. There is a pregnant woman holding her belly. An inset illustration shows a fetus within the amniotic sac. Transplacental transmission may occur to the fetus during pregnancy. Parturition may occur during the birth of the newborn.

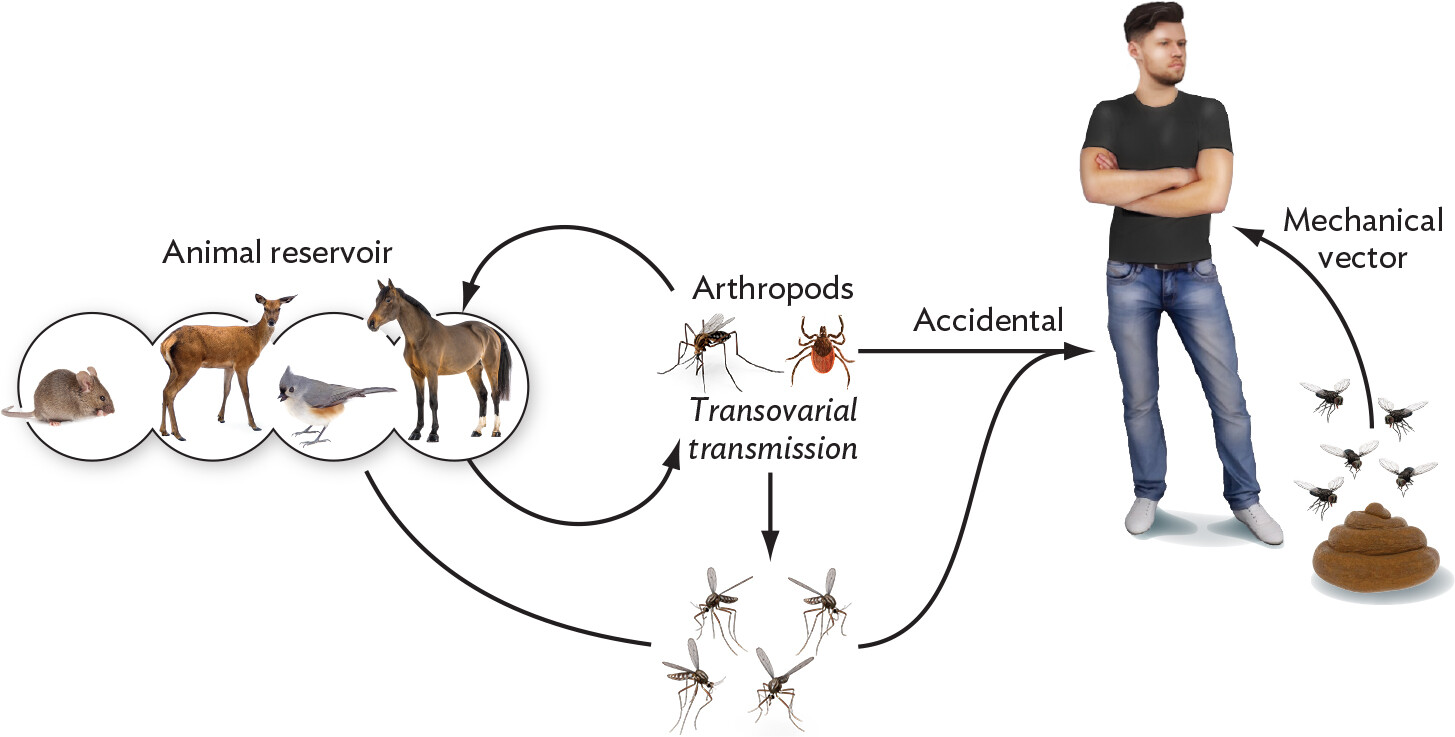

An illustration explaining accidental transmission from arthropod vectors. The cycle has four main players; The animal reservoir, Adult arthropods, juvenile arthropods, and a human. The animal reservoir includes a mouse, a deer, a bird, and a horse. An arrow connects the animal reservoirs to the next group, the adult arthropods, a mosquito and a tick. another arrow completes the circle back to the animals. From the adult arthropods, two arrows extend. One extends to juvenile arthropods, and is labelled Transovarial transmission. The second arrow points to the human and is labelled Accidental. This juvenile arthropod image of mosquitos is also connected via arrow to the animal reservoir and the human. An unconnected arrow points from a pile of feces with file buzzing over it to the human, and is labelled mechanical vector.

|

Table 2.2 Terms Used to Describe Disease Transmission and Frequency |

||

|

Term |

Definition |

Examples |

|

Direct contact |

Intimate interaction between two people. |

Touching, kissing, sexual intercourse (mononucleosis or gonorrhea) |

|

Indirect transmission (indirect contact) |

Transmission of an infectious agent from one person to another requiring an intermediary, either inanimate or living. |

Mosquito (malaria); sharing a spoon or fork (strep infection) |

|

Vehicle transmission (fomites) |

Form of indirect transmission whereby an infectious agent is transferred to an inanimate object (fomite) by one person touching it and then transferred to another person touching the same object, or by ingesting contaminated food or water, or by inhaling the agent in air. |

Doorknobs, shared utensils (influenza, strep infection) |

|

Vehicle |

Means of pathogen transmission, as by air, food, or liquid. |

Air (anthrax), food (Salmonella), water (Leptospira) |

|

Vector |

Living carrier of an infectious organism. |

Mosquitoes (West Nile), fleas (Yersinia pestis), body lice (Rickettsia) |

|

Aerosol |

Organisms in air suspension. |

Sneezing (rhinovirus), air-conditioning or heating (Legionella), water from a shower (Mycobacterium avium) |

|

Reservoir |

Nonhuman animal, plant, human, or environment that can harbor the organism; a reservoir may or may not exhibit disease. |

Cattle (E. coli O157:H7), horses (West Nile virus), alfalfa sprouts (Salmonella) |

|

Fecal-oral route |

Pathogen exits the body in feces, which contaminates food, water, or fomite; pathogen is introduced into a new host by ingestion. |

Shigella, E. coli, Salmonella, rotavirus |

|

Respiratory route |

Pathogen enters the body through breathing. |

Influenza, Streptococcus pneumoniae |

|

Urogenital route |

Pathogen enters the body through urethra or vagina. |

Urinary tract infections (nonsexual transmission), syphilis (sexual contact) |

|

Parenteral route |

Pathogen enters the body through insect bite or needle injection. |

Malaria, HIV (AIDS) |

|

Endemic |

Disease (humans) is present at a constant, usually low, rate in a specific geographic location; pathogen is usually harbored in an animal or human reservoir. |

Lyme disease, common cold |

|

Epidemic |

Number of disease cases exceeds the endemic level. |

Influenza, plague |

|

Pandemic |

Worldwide epidemic. |

Influenza, plague, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus) |

There are at least five forms of horizontal transmission: direct contact, airborne, indirect transmission, vehicles, and vectors. Some of them overlap. Pathogens that spread horizontally from person to person, such as rhinovirus, are often transferred by direct contact via handshaking or even sexual contact (see Figure 2.10A). Handshaking is a very efficient way to horizontally transmit pathogens. A hand contaminated with a viral or bacterial pathogen can pass the pathogen to several people just by handshaking. Newly contaminated people can then infect themselves by touching their eyes or mouth. During the COVID-19 pandemic, handshaking became socially taboo.

Rhinoviruses and other common cold and respiratory pathogens can be passed directly from person to person through the air by sneezing (airborne transmission). A sneeze will spray an aerosol containing massive numbers of microbe-laden secretion particles into the air, which people nearby can inhale (Figure 2.11).

A photograph of a man sneezing. The longitudinal plane of the image shows a copious amount of moisture droplets and aerosoles projecting from the mans mouth, clearly visible against the black background.

Indirect transmission is a broad term that covers all types of transmission that do not require direct contact. Respiratory viruses, for instance, can be transferred by touching inanimate objects (fomites) that were contaminated by pathogen-laden aerosols spewed forth by someone else. Fomites can include contaminated utensils (such as a fork or a pen), towels, cloth handkerchiefs, and doorknobs (Figure 2.10B). Many gastrointestinal infectious agents can be indirectly transmitted between people or animals when food or water becomes contaminated with fecal material containing the pathogen. This is why handwashing after using the bathroom is an important control measure. Indirect transmission via fomites, food, or water is also called vehicle transmission.

More complex horizontal transmission cycles involve vectors, usually insects or ticks (arthropods), and reservoirs, animals or environments that harbor an infectious agent (Figure 2.10D; discussed more below). The housefly is a simple mechanical vector that can transmit disease by landing on contaminated material (for example, feces) and then carrying any pathogens present to a living host such as a human or nonhuman animal, or to food (for example, an oatmeal cookie), or to inanimate fomites. In contrast, mosquito and tick vectors (biological vectors) can transmit infectious agents by biting an infected reservoir host. They ingest the pathogen and then pass it to a new host during a subsequent blood meal (Figure 2.10D). The tick in Case History 2.1 served as the biological vector that passed Rickettsia rickettsii from infected rodents in the forest to Emma Katherine. An infectious disease that is primarily seen in animals but can be transmitted to humans, either by biological vector or by other means, is called a zoonotic disease (examples include West Nile virus and Lyme disease).

Sometimes a vector also serves as the reservoir for an infectious disease. The mosquito vector Aedes, for example, can horizontally transfer many viral pathogens, including the yellow fever virus, from infected to uninfected individuals (Figure 2.12). Outbreaks of yellow fever are currently (2023) plaguing areas of Africa as well as Central and South America. An infected Aedes mosquito can also pass the yellow fever virus to its offspring via infected eggs. This is a form of vertical transmission called transovarial transmission (again, see Figure 2.10D).

A black and white portrait photo of Walter Reed. Reed is facing the camera with a neutral expression on his face. He is wearing formal military attire consisting of a long dark jacket with vertical lines of buttons and embroidered shoulder pads. His hair is cut short and combed neatly.

A photo of a mosquito sucking blood and a transmission electron micrograph of a flavivirus. A photo of the Aedes aegypti mosquito sucking blood from a human arm. The mosquito abdomen is engorged with blood. The mosquito has an elongated ovoid body. It has a black exterior with white stripes. Six spindly legs extend from the mosquitos body. Its long, thin proboscis punctures the skin of the arm. A transmission electron micrograph of the flavivirus that causes yellow fever. The virus particles are roughly spherical and have a grainy texture. They have been colorized orange to yellow in this micrograph. The particles are each about 50 nanometers in diameter.

Note: Only female mosquitoes and ticks take blood meals. They need the blood to develop their eggs. Male mosquitoes do not bite but feed on plant nectar. Adult male ticks will attach to a host but do not feed and cannot transmit disease. Once a male tick mates with a female, the male dies.

Note: Only female mosquitoes and ticks take blood meals. They need the blood to develop their eggs. Male mosquitoes do not bite but feed on plant nectar. Adult male ticks will attach to a host but do not feed and cannot transmit disease. Once a male tick mates with a female, the male dies.

Although yellow fever is not a problem in the United States today, a closely related virus called West Nile virus (WNV) claims several victims each year. WNV is also transmitted to humans by a mosquito vector (Culex) that transovarially passes the virus though its eggs. Because insects and ticks can transmit many pathogens, strategies to repel or kill arthropods, or prevent them from laying eggs, are effective ways to halt the spread of disease. Interventions include spraying insecticide in a community during egg-hatching season or using other microbes as assassins “trained” to kill the vector. For example, the insect virus baculovirus has been developed to kill the Culex mosquito that carries West Nile virus. The advantage of these vector-targeting microbes is that, unlike many chemical insecticides, they do not kill other insects or animals.

As mentioned earlier, a reservoir of infection is an animal (often a bird, rat, horse, insect, or arthropod) or an environment (such as soil or water) that normally harbors the pathogen. The animal reservoir carrying the pathogen might not even exhibit disease. For yellow fever, monkeys, which can exhibit symptoms, serve as the animal reservoir. However, the mosquito vector is also a reservoir for this virus because the insect can pass the virus to future generations of mosquitoes through vertical transmission. Likewise, the tick in Case History 2.1 served as both a reservoir and a vector for Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

In contrast to the yellow fever virus, the virus causing eastern equine encephalitis (EEE, a potentially lethal brain infection seen in some parts of the United States) uses birds as a reservoir. The microbe is normally a bird pathogen transmitted from bird to bird via a mosquito vector. The virus does not persist in the insect, but transmission to new avian hosts keeps the virus alive. Humans or horses entering geographic areas harboring the disease (called endemic areas) can also be bitten by the mosquito. When this happens, they become accidental hosts and contract the disease. The EEE virus does not replicate to large numbers (titers) in mammals, so horses and humans are poor reservoirs for the virus. In avian hosts, however, the virus does replicate to large numbers. Reservoirs are crucial for the survival of a pathogen and serve as a source of infection. If the EEE virus had to rely on humans to survive, it would cease to exist because of limited replication potential and limited access to mosquitoes.

A special type of reservoir is the asymptomatic carrier—a person who harbors a potential disease agent but does not exhibit signs or symptoms of disease. This is how Neisseria meningitidis, an important cause of meningitis, remains in a population. The bacterium has no animal reservoir other than humans, so where does it go between outbreaks? It colonizes the nasopharynx (the area behind the nose down to the throat) of unsuspecting hosts whose immune systems keep the bacterium out of the bloodstream. A simple sneeze from the carrier, however, can aerosolize the pathogen and transfer it to a susceptible host, who then contracts the disease and passes the organism to others. Asymptomatic carriers were yet another major concern during the COVID-19 pandemic.

CASE HISTORY 2.2

The Third Pandemic

A photo of a rat. The rat has dark grey fur. It has a long, thin tail and pink feet.

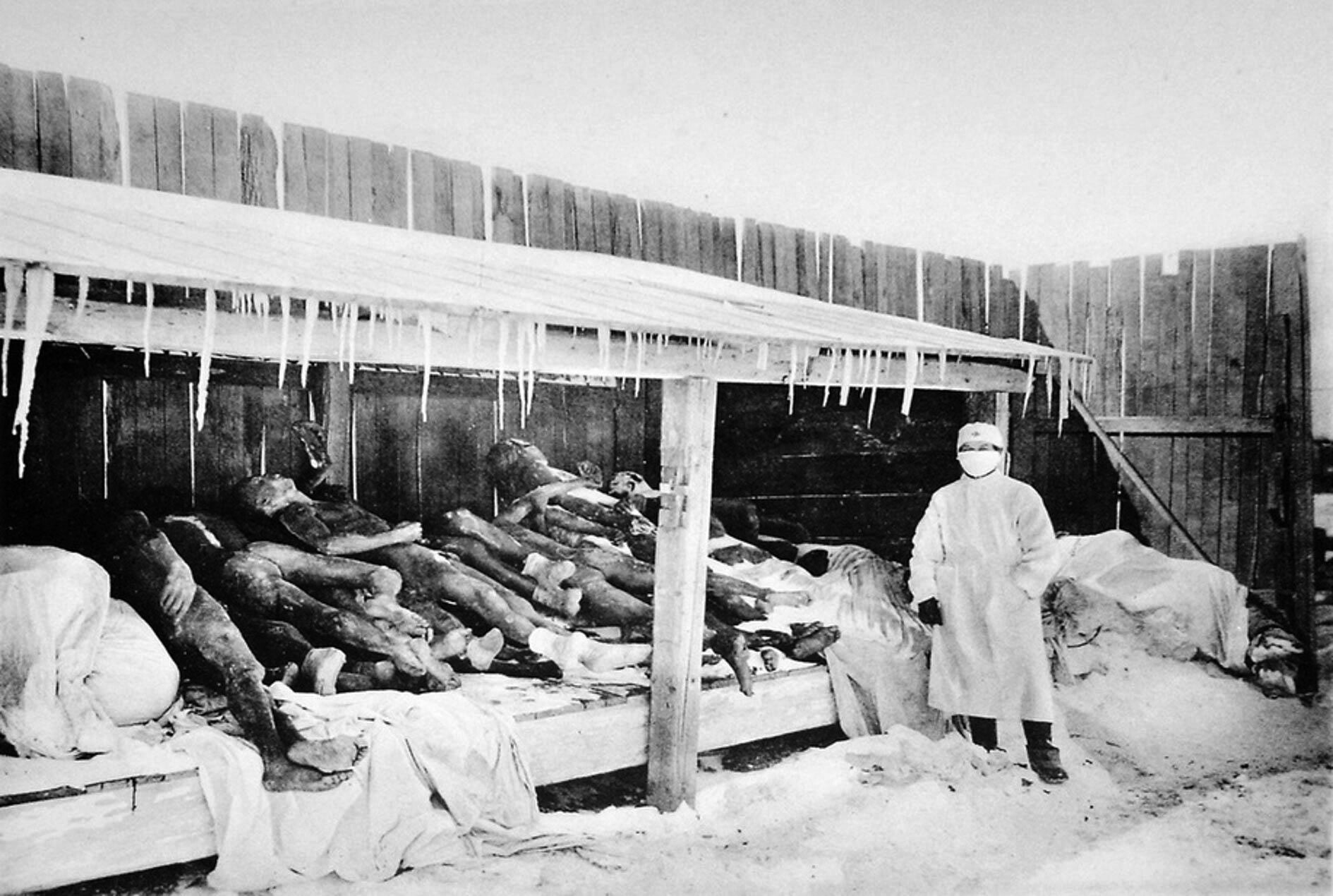

A historic black and white photo of a plague pit from the 1910 plague pandemic. There is a wooden shed like structure containing the bodies of multiple plague victims. A worker stands nearby in full P P E. The worker is wearing a face mask, a head cover, a lab coat, plastic boots, and protective gloves. Snow covers the ground. A high wooden fence surrounds the area.

This case is about bubonic plague, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Y. pestis is transmitted from infected rats to humans by the rat flea, whose bite delivers bacteria-laden saliva. Like the earlier case of Rocky Mountain spotted fever (Case History 2.1), this case involves vectors, reservoirs, and infection cycles, but it also introduces the concept of pandemics. Several devastating pandemics of plague have occurred over the centuries, including the Black Death that killed more than a third of Europe’s population in the fourteenth century. Plague is still with us today. It is endemic in Madagascar, where 200–700 cases are seen every year, and even the United States sees a few cases most years (see Chapter 21).

We have all heard the terms “endemic,” “epidemic,” and “pandemic” in reference to disease, but what do they mean? An endemic disease is always present in a community at a constant, usually low, rate. Often an animal reservoir harbors the disease-causing organism. An epidemic occurs when many cases of a disease develop in a community over a short time. An organism need not be endemic to an area to cause an epidemic. A pandemic is essentially a worldwide epidemic, although not every country needs to be affected. The Third Pandemic of plague (1855–1959) that started in China spread to many other areas of the globe, carried by people (and rats) as they traveled. More recently (2019), the COVID-19 pandemic caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, also thought to originate in China, rapidly spread to all but one country on Earth. Turkmenistan claims no cases, but that claim is suspect.

Although many microbes can cause epidemics, surprisingly few have proved capable of causing pandemics. The major organisms known to have caused pandemics are the bacteria Y. pestis (bubonic plague) and Vibrio cholerae (cholera); and the viruses influenza, HIV, and SARS-CoV-2 (Table 2.3). You might wonder why more organisms do not cause pandemics. There are several reasons. The organism must be easily transmitted from person to person. Such transmission is most readily accomplished if the microbe causes a respiratory disease and becomes airborne through coughing. The organism must also cause disease at a relatively low infectious dose.

|

Table 2.3 Examples of Deadly Pandemics |

|||

|

Disease |

Organism |

Years (Number of Deaths) |

Link to Disease Coverage |

|

Influenza |

Influenza virus |

1918–1919 (40 million–50 million dead) 1957 (2 million dead) 1968 (1 million dead) 2009 (150,000–500,000 dead) |

|

|

Bubonic plague |

Yersinia pestis |

541–542 CE (Plague of Justinian a; the number of dead is unclear but is in the millions) 1347–1351 (Black Death; 25 million dead) 1855–1959 (Third Pandemic; 137 million dead) |

|

|

Cholera |

Vibrio cholerae |

Seven pandemics: the first, in 1816, began in India (over 15 million dead); the third, in 1852, began in Russia (over 1 million dead); the seventh, in 1961, began in Indonesia (ongoing) |

|

|

AIDS |

Human immunodeficiency virus |

1981– (over 25 million dead) |

|

|

COVID-19 |

Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 |

2019–2023 (no longer a global emergency as of May 2023) |

Chapter 26 |

It is obvious why COVID-19 is called a pandemic: it is airborne, is easily transmitted, and has caused over 760 million cases worldwide. HIV is not an airborne infectious agent, so why is AIDS a pandemic? HIV does not rapidly kill its host, and because the virus tampers with the host immune system, the virus is not readily killed. Thus, over a person’s life, ample opportunity exists to transmit the virus to a partner, especially considering that the symptoms of AIDS can take years to appear. During this extended prodromal period, the virus is present in an assortment of body fluids and is easily transmitted by various sexual practices. Infected people having multiple sexual partners, straight or gay, combined with frequent air travel and the disease’s inability to be cured, has led to the rapid spread of this virus around the globe (Chapter 23 contains more on HIV and treatments that can suppress its transmission.)

In some parts of the world, such as sub-Saharan Africa, HIV has actually become endemic. An infection like HIV that relies on person-to-person transmission becomes endemic when each person who becomes infected with the disease, on average, passes it to one other person. In this way, the infection doesn’t die out, nor does the number of infected people increase exponentially; the infection is now said to be in an endemic steady state. An infection that starts as an epidemic will eventually either die out or reach the endemic steady state, depending on disease virulence and mode of transmission.

You might now ask, if AIDS is considered a pandemic, why isn’t the common cold considered a pandemic? Every country around the globe deals with seasonal epidemics of the common cold. Why not call it a pandemic? The reason here is technical. Pandemics are caused by a single strain or closely related strains of a single microbe—for example, H1N1 influenza. The common cold, however, is caused by many different types of viruses (rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, adenoviruses) and many strains of viruses (160 for rhinoviruses alone). Plus, common-cold symptoms are not severe, and people don’t typically die. Viral replication, pathogenesis, and the diseases of influenza and the common cold will be described in more detail in Chapters 12, 18, and 20.

As noted earlier, infections that normally afflict animals but can be transmitted to humans are called zoonotic diseases. Humans typically contract a zoonotic disease after accidentally encountering the animal reservoir. Bubonic plague (Case History 2.2) is a case in point. The bacterium usually infects rodents but can be transferred to humans by a flea bite. Other examples include Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi), eastern equine encephalitis (EEE virus), and Rocky Mountain spotted fever (Rickettsia rickettsii), whose agents typically infect white-footed mice, birds, and ticks, respectively, but can infect humans if they get close enough.

Animal and insect reservoirs can also function as “incubators” for new infectious diseases yet to emerge in humans. For example, two different strains of influenza virus can infect the same animal (usually pigs) at the same time. When both virus strains infect the same cell, the viruses can exchange discrete chunks of their RNA genomes, and a new virus—more infectious and deadly than either of the original forms—can emerge. Here are some other examples of how infectious agents are thought to have crossed between species:

Clearly, the animal kingdom serves as an important incubator of new infectious diseases that can cross species.

Note: Most, but not all, pandemics have originated in Asia or Africa. This fact is due to a variety of factors, such as human overpopulation in tropical areas that harbor many animals and evolving pathogens, urbanization that brings animal and human habitats closer to each other, the presence of crowded live animal markets on both continents, and illegal bushmeat markets popular in Africa. Chapter 26 will further explore the origins of pandemics.

Note: Most, but not all, pandemics have originated in Asia or Africa. This fact is due to a variety of factors, such as human overpopulation in tropical areas that harbor many animals and evolving pathogens, urbanization that brings animal and human habitats closer to each other, the presence of crowded live animal markets on both continents, and illegal bushmeat markets popular in Africa. Chapter 26 will further explore the origins of pandemics.

SECTION SUMMARY

Thought Question 2.5 Yellow fever is a viral disease found primarily in South America and Africa. The symptoms include a high fever, headache, and muscle aches, and the disease can lead to kidney and liver failure. Liver damage produces a yellowing of skin (jaundice), giving the disease its name. The virus can be spread directly from one person to another by way of a mosquito whose bite can transmit the virus from an infected person to an uninfected person. However, HIV, another virus found in blood, cannot be transmitted by a mosquito bite. Why might that be?

Mosquitoes that bite humans do not transfer blood from one person into another; they transmit only mosquito saliva. HIV does not replicate in mosquito cells and is quickly inactivated. In contrast, yellow fever virus can replicate in mosquito cells and can survive for long periods. Another important factor is that once mosquitoes are fed, they do not immediately bite another person. HIV will be inactivated long before another meal is needed. Yellow fever virus, however, will replicate in the insect, so it can be found in saliva and can be transmitted.