SECTION OBJECTIVES

- Explain how a stain reveals additional information about a microscopic object.

- Describe how the Gram stain distinguishes two classes of bacteria.

SECTION OBJECTIVES

CASE HISTORY 3.2

400,000 Sickened by Parasite

A photo of an Anopheles mosquito with its proboscis extended. The mosquito has a narrow, ovoid thorax and abdomen. Six spindly legs extend outward from the thorax to stabilize the mosquito’s body. A set of clear wings extend back from the thorax over the abdomen. The mosquito head narrows into a long, thin proboscis, which looks similar to a needle.

How can microscopy help us diagnose a case of malaria? The diagnosis of malaria offers a clinical application of microscopy using a blood sample that is fixed and treated with the Giemsa stain (Figure 3.17). The Giemsa stain contains eosin, a negatively charged dye that binds red blood cells (RBCs), and methylene blue, a positively charged dye that binds the negatively charged phosphate groups of DNA. The methylene blue specifically stains the DNA-containing nucleus of the malarial parasite. Giemsa stain reveals both the “ring form” stage of the parasite, growing within an RBC, and the “gametocyte” stage that develops outside the host cell, ready for transmission to the next host.

A light micrograph of the ring stage of Plasmodium falciparum inside red blood cells. The red blood cells appear as pale purple circles, and the parasites appear as smaller, dark purple rings within several of the red blood cells. Each blood cell is about 8 micrometers in diameter.

Stained blood samples play a crucial role in malaria diagnosis, which is often a challenge to obtain in remote rural regions where malaria is prevalent. New technology such as cell phone microscopy aims to make such tests available in developing countries (see IMPACT).

Fixation and staining are procedures that enhance detection and resolution of microbial cells. These procedures kill the cells and stabilize the sample on a slide. In fixation, cells are made to adhere to a slide in a fixed position. Cells may be fixed with methanol or by heat treatment to denature (unfold) the cell’s proteins, whose exposed side chains then adhere to the glass. A stain absorbs much of the incident light, usually over a wavelength range that results in a distinctive color. The use of chemical stains was first developed in the nineteenth century, when German chemists used organic synthesis to invent new coloring agents for clothing. Clothing was made of natural fibers such as cotton or wool, so a substance that dyed clothing was likely to react with biological specimens.

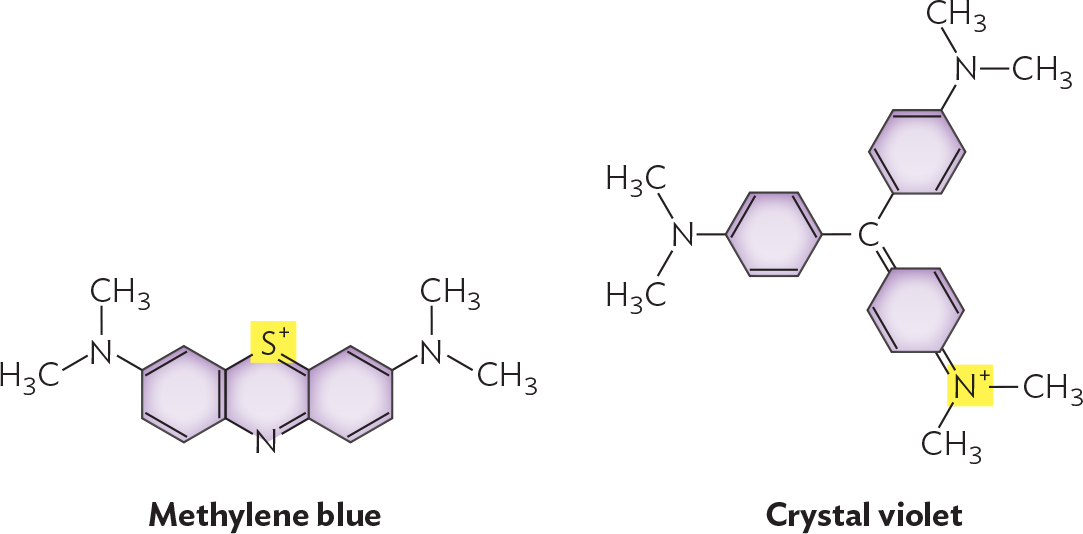

How do stains work? Most stain molecules contain double-bond systems that absorb visible light (Figure 3.18) and one or more positive charges that bind to negative charges on the bacterial cell envelope (discussed in Section 5.3). Different stains vary with respect to their strength of binding and the degree of binding to different parts of the cell.

Illustrations of the chemical structures of methylene blue and crystal violet. Methylene blue consists of three 6 carbon rings fused in a row. The rings on each end are bound to an amine group with two methyl groups. The non fused carbons in the middle ring are replaced with S superscript plus at the top and N at the bottom. Crystal violet consists of a central carbon atom that is single bonded to two benzene rings. These two rings are each bound to an amine group with two methyl groups. The central carbon is also double bonded to a hexagonal ring with two double bonds. The ring is double bonded to an N superscript plus which is further bonded to two methyl groups.

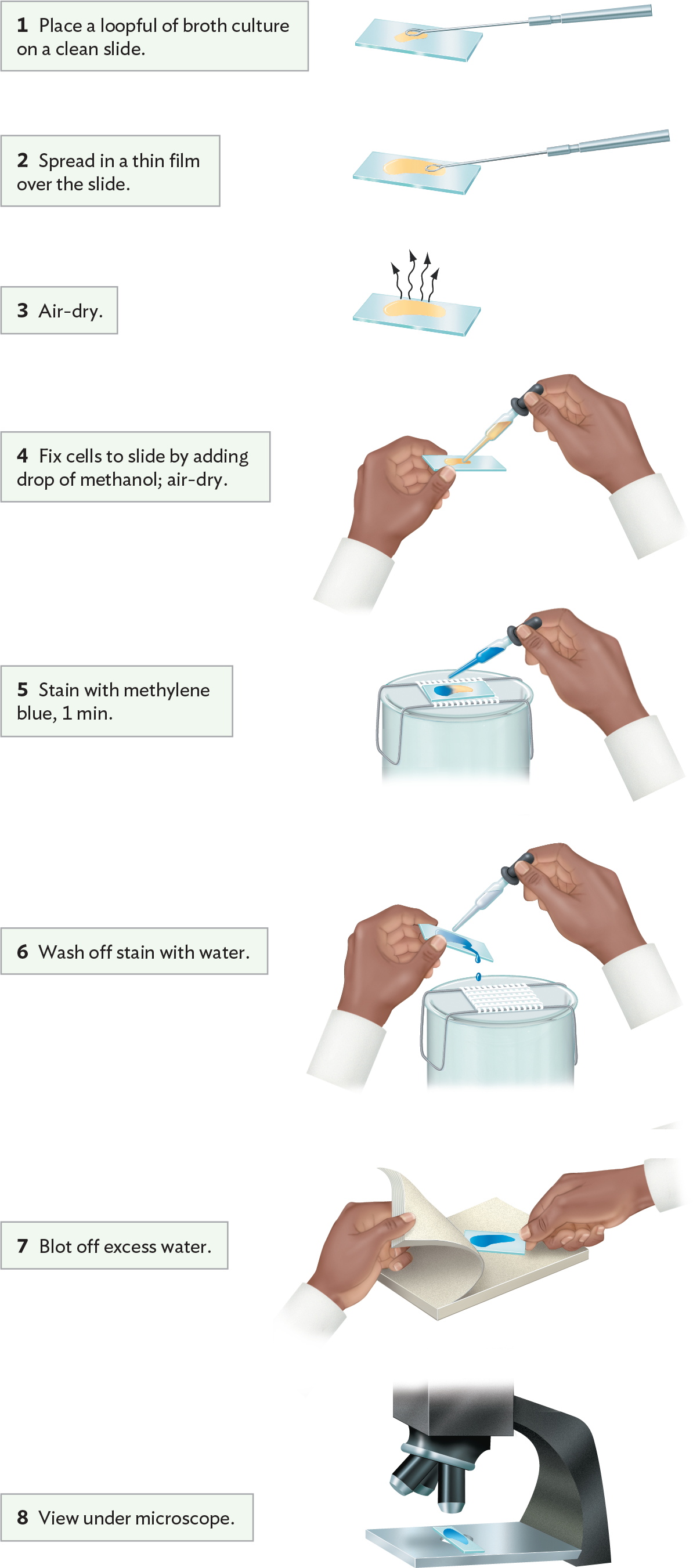

A simple stain adds dark color specifically to cells but not to the external medium or surrounding tissue. The most commonly used simple stain is methylene blue, originally used by Robert Koch to stain anthrax bacteria. A typical procedure for fixation and staining is shown in Figure 3.19. First, a drop of culture is fixed on a slide by treatment with methanol or by heat on a slide warmer. Either treatment denatures cell proteins, exposing side chains that bind to the glass. The slide is then flooded with methylene blue solution. The positively charged molecule binds to the negatively charged cell envelope. After excess stain is washed off and the slide has been dried, it is observed under high-power magnification.

A diagram explaining a procedure for simple staining with methylene blue. Step 1 reads, Place a loopful of broth culture on a clean slide. A wire loop is used to place a drop of yellow broth culture on a glass slide. Step 2 reads, Spread in a thin film over the slide. The loop is used to pull the culture across the slide in a thin layer. Step 3 reads, Air dry. The glass slide is left on a flat surface so that the layer of broth culture can dry. Step 4 reads, fix cells to slide by adding drop of methanol, then air dry. An individual uses a dropper tool to apply a drop of methanol to the slide. Step 5 reads, stain with methylene blue for 1 minute. The glass slide is positioned on a wire rack over a collection basin. An individual uses a dropper tool to apply a drop of methylene blue stain to the slide. Step 6 reads, wash off stain with water. An individual holds the glass slide at an angle over the basin. With their other hand, they use a dropper tool to wash the excess stain from the slide with a gentle stream of water. Step 7 reads, Blot off excess water. The slide is place between sheets of blotting paper. The paper is applied to the slide with steady pressure to remove excess moisture. Step 8 reads, view under microscope The stained slide is positioned on the stage beneath the objective lenses of a microscope.

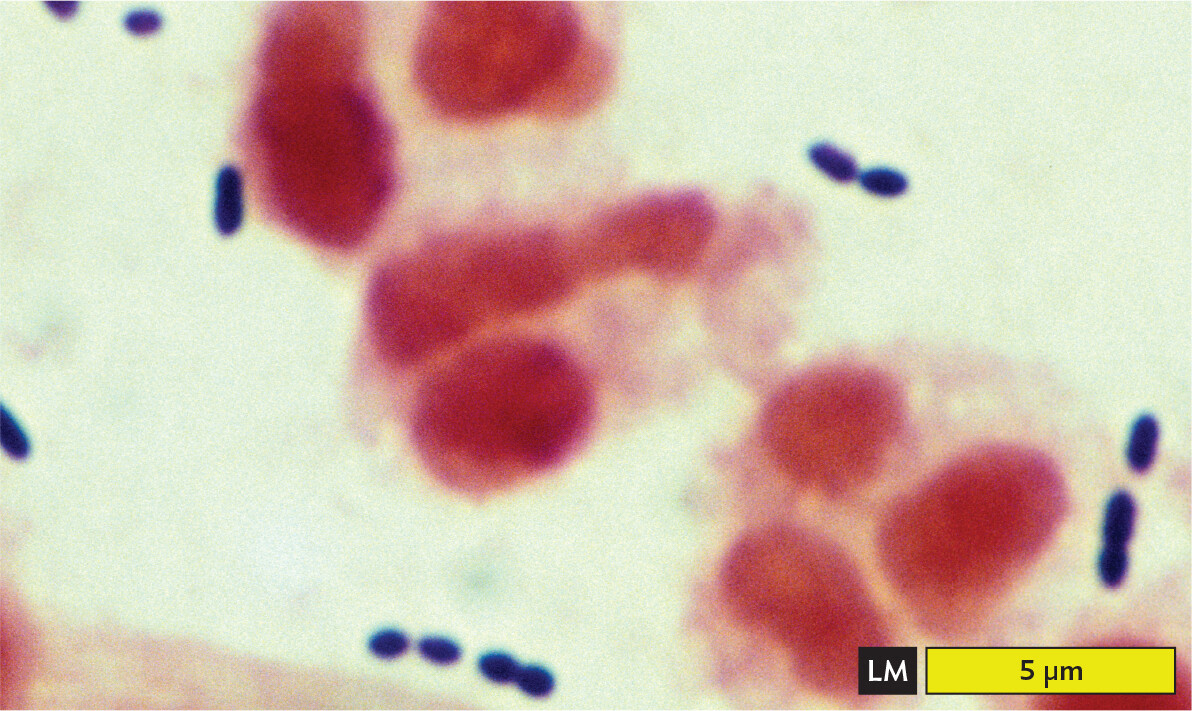

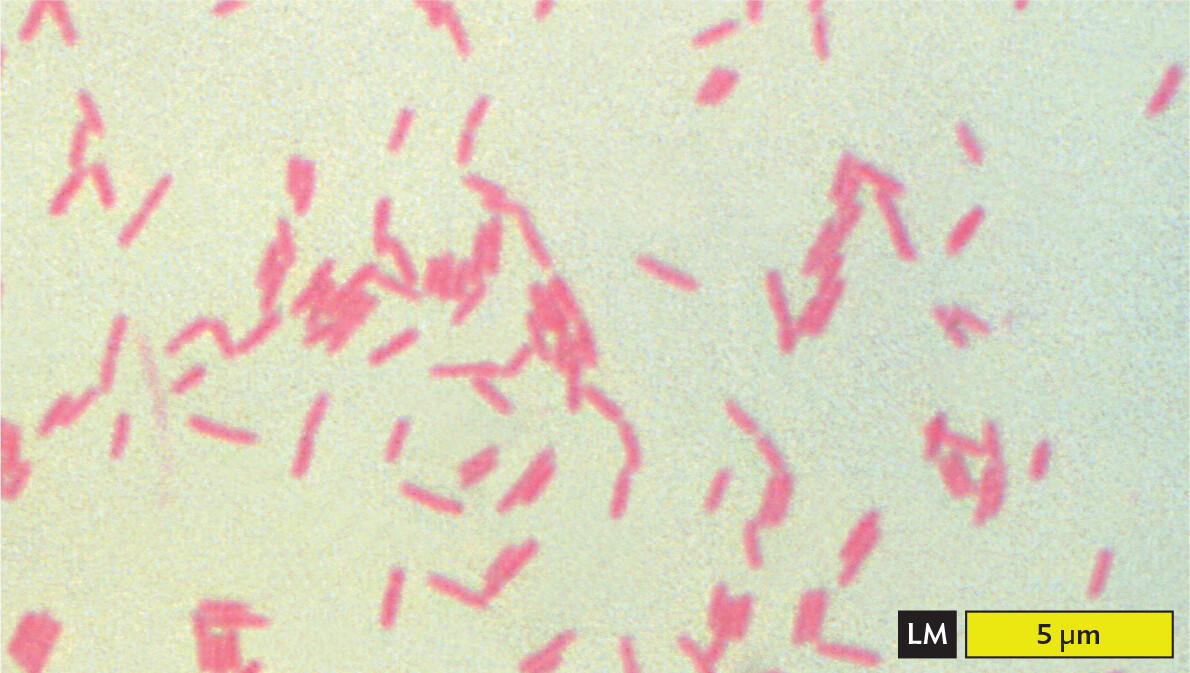

Certain kinds of stain distinguish two different kinds of cell, such as bacteria versus human cells. A stain that distinguishes two types of cells or cell components is called a differential stain. The most famous differential stain is the Gram stain, devised in 1884 by the Danish physician Hans Christian Gram (1853–1938). Gram first used the Gram stain to distinguish pneumococcal bacteria (Streptococcus pneumoniae) from human lung tissue. A similar use of the Gram stain is seen in Figure 3.20A, where S. pneumoniae bacteria appear dark purple against the pink background of human epithelial cells. However, not all species of bacteria retain the purple stain in their cell wall. An example of a bacterium that fails to retain the stain, making it Gram-negative, is Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which as recently as 2019 caused a series of infections of surgical wounds in the United States and Mexico (Figure 3.20B). Different bacterial species are classified as Gram-positive or Gram-negative, depending on whether or not they retain the purple stain.

A light micrograph of a gram stained sputum specimen from a patient with pneumonia containing Gram positive cells. There are several ovoid to spherical dark blue purple Gram positive Streptococcus pneumoniae cells. These are arranged in short chains. The chains float around the edges of a few irregularly shaped human epithelial cells, which are stained pink in this micrograph. The bacterial cells are each about 1 to 1.5 micrometers in length and about 0.5 micrometer in width. The epithelial cells are much larger, each greater than 5 micrometers in maximum dimension.

A light micrograph of Gram negative Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells. There are numerous light pink rod shaped bacteria in the field of view. Some are separate and some are in loose clusters. Each bacterium is about 2 micrometers in length and 0.5 micrometer in width.

A photo of a cell phone and a very small microscope with a glass slide under it. An image of the slide can be seen on the screen of the cell phone. Control buttons also appear to be available on the phone screen.

impact

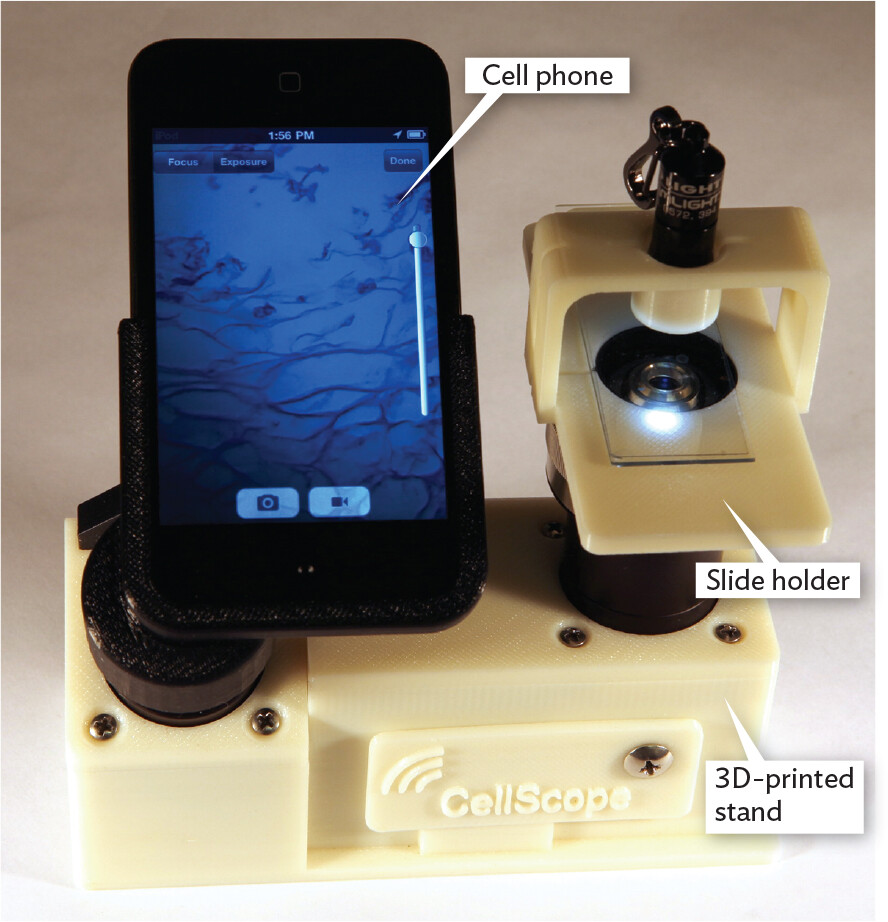

The CellScope: A Cell Phone Microscope

Microscopy plays a key role in diagnosing many diseases, including malaria and tuberculosis. But microscopy is often unavailable in the developing world, particularly in remote rural areas where few medical facilities exist. A solution to this problem was devised by Daniel Fletcher, professor of bioengineering at UC Berkeley. Fletcher and his students designed an inexpensive optical system that can be attached to a cell phone camera (Figure IMPACT 3.1). The phone is thus converted to a handheld microscope, called the CellScope. The CellScope obtains remarkably high-quality images of blood films, showing malaria infection and misshapen red blood cells. The optics can even include fluorescence filters, allowing fluorescent antibody detection of tuberculosis bacteria in a sputum sample. Fluorescence requires illumination with light at one wavelength, followed by detection of light emitted by the sample at a different wavelength (explained in Section 3.5).

A photo of the Cell Scope, which is a microscope made from a cell phone. A cell phone is positioned next to a very small microscope. The microscope has an objective lens, a slide beneath it, and light shining on part of the slide. The surface supporting the slide is called the slide holder. The base is a 3 D printed stand that connects both the phone and the small microscope. Cell Scope is printed on the base. An image of the specimen on the slide can be seen on the phone screen.

The optical attachment includes an eyepiece, an objective lens, and a sample holder. Illumination is provided by a low-energy light-emitting diode (LED). For fluorescence, the attachment includes special filters for detecting the excitation and emission wavelengths. Even with inexpensive lenses, the CellScope has achieved resolution of 1.2 µm, enabling detection of malaria parasites and Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria.

The cell phone’s computer elements can manipulate images obtained through the CellScope. The Fletcher lab at UC Berkeley continues to develop applications of “telemicroscopy” for remote communities around the globe. Users can transmit images through the mobile wireless network, which reaches many remote regions. Distant medical professionals can interpret the transmitted images. So far, workers have field-tested the device in several countries, and clinical comparison trials are under way. For example, the CellScope has been used to detect tuberculosis at Hanoi Lung Hospital, Vietnam; Schistosoma parasites at the University of Yaoundé, Cameroon; and cytomegalovirus retinitis at Chiang Mai University, Thailand.

What other kind of infections do you think you could diagnose using a CellScope?

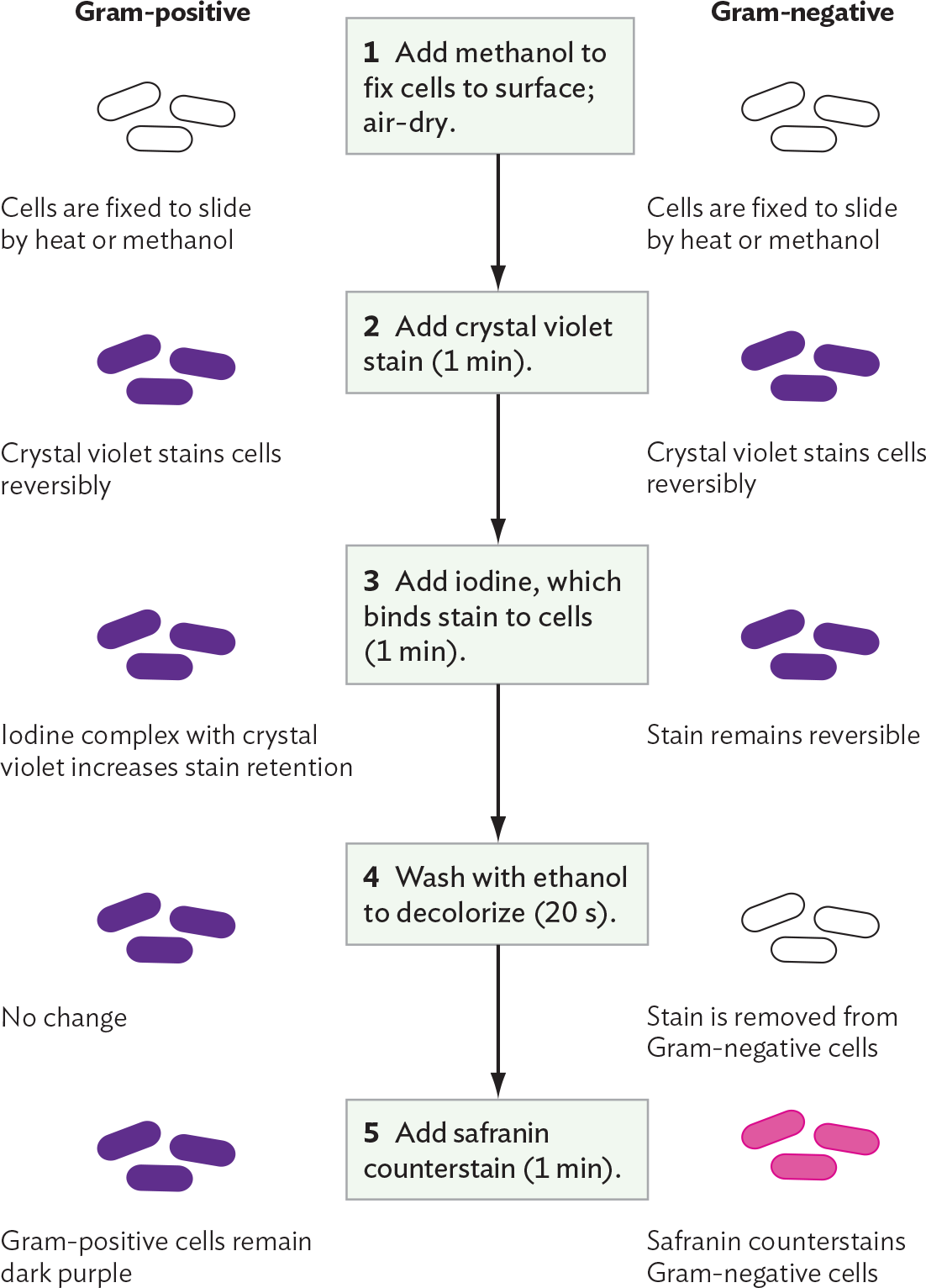

In the Gram stain procedure (Figure 3.21), a dye such as crystal violet binds to the bacteria cell wall; it also binds to the surface of human cells, but less strongly. After the excess stain is washed off, a mordant, or binding agent, is applied. The mordant used is iodine solution, which contains iodide ions (I–). The iodide ions form complexes with the positively charged crystal violet molecules trapped inside the cells. The crystal violet–iodide complex is now held more strongly within the cell wall. The thicker the cell wall, the more crystal violet–iodide complexes are retained.

A diagram explaining the Gram staining procedure and differential stain uptake by Gram positive or Gram negative cells. Step 1 reads, Add methanol to fix cells to surface, then air dry. Both the Gram positive and Gram negative cells are fixed to the slide by heat or methanol. The cells are not stained so they are translucent. Step 2 reads, Add crystal violet stain for 1 minute. Crystal violet stains both the Gram negative and the Gram positive cells purple reversibly. Step 3 reads, Add iodine, which binds stain to cells for 1 minute. In the Gram positive cells, the iodine complex with crystal violet increases stain retention. In the Gram negative cells, the stain remains reversible. Both cell types are still purple at this stage. Step 4 reads, wash with ethanol to decolorize for 20 seconds. In the Gram positive cells, there is no change. The cells remain purple. In the Gram negative cells, the stain is removed. The cells are translucent again. Step 5 reads, add safranin counterstain for 1 minute. The Gram positive cells remain dark purple. The safranin counterstains the Gram negative cells, so they are pink.

Animation: Microscopy and Staining

Next, a decolorizer—here, ethanol—is added for a precise interval (typically 20 seconds). The decolorizer removes loosely bound crystal violet–iodide complexes, but Gram-positive cells retain the stain tightly. The Gram-positive cells that retain the stain appear dark purple, whereas the Gram-negative cells are colorless. The timing of the decolorizer step is critical because if it lasts too long, the Gram-positive cells, too, will release their crystal violet stain. In the final step, a counterstain, safranin, is applied. This process allows the visualization of Gram-negative material, which the safranin stains pale pink.

The Gram stain procedure was originally devised to distinguish bacteria (Gram-positive) from human cells (Gram-negative or unstained). Microscopists soon discovered, however, that many important species, such as the intestinal bacterium Escherichia coli and the nitrogen-fixing symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti, do not retain the Gram stain. It turns out that Gram-negative species of bacteria possess a thinner and more porous cell wall than Gram-positive species. A Gram-negative cell wall has only a single layer of peptidoglycan (sugar chains cross-linked by peptides), which more readily releases the crystal violet–iodide complexes. By contrast, a Gram-positive cell such as Staphylococcus aureus, a cause of toxic shock syndrome and wound infections, has multiple layers of peptidoglycan. The multiple layers retain enough stain to make the cell appear purple.

Among bacteria, the Gram stain distinguishes many types of bacteria, including two groups with distinctive cell wall structures: Proteobacteria (such as E. coli and Proteus), with a thin cell wall plus an outer membrane (Gram-negative), and Firmicutes (such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus), with a multiple-layered cell wall but no outer membrane (Gram-positive). The outer membrane of Proteobacteria (see Chapter 5) often possesses important pathogenic factors, such as the lipopolysaccharide endotoxins that cause shock. During the Gram stain procedure, however, the decolorizing wash with ethanol disrupts the outer membrane, allowing most of the crystal violet–iodide complex to leak out.

The Gram stain emerged as a key tool for the biochemical identification of species, and it remains essential in the clinical laboratory. However, the Gram stain is reliable only for freshly cultured bacteria. Some Gram-positive cells, such as Bacillus anthracis (the cause of anthrax), fail to retain stain once the cells run out of nutrients. Still other groups of bacteria, including Lactobacillus species common in the oral cavity and gastrointestinal tract, may stain either positive or negative (known as Gram-variable) and are thus not distinguished by the Gram stain. Bacterial diversity and identification are explored further in Chapter 10.

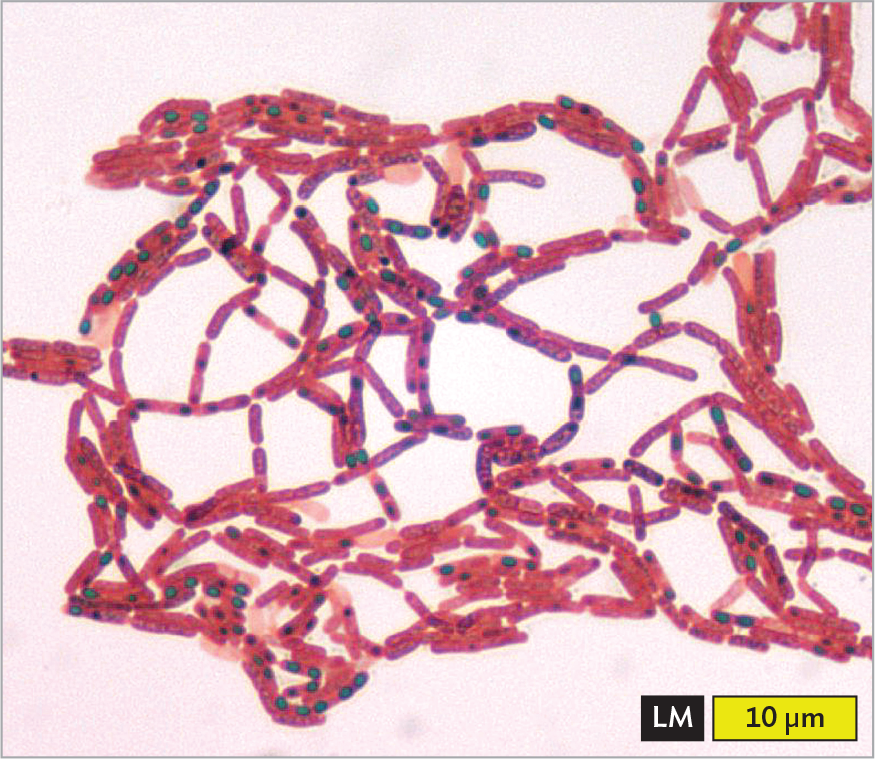

Other differential stains applied to various prokaryotes are illustrated in Figure 3.22. These include acid-fast stains, endospore stains, negative stains, and antibody stains:

A light micrograph of Mycobacterium tuberculosis stained with Ziehl Neelsen acid fast stain. The slide shows a section of mouse lung. The lung cell nuclei are stained blue, which appears in a range of shades across the slide. The lung cells are circular to irregularly shaped and packed tightly together. Some clear spaces are present between the cells. Among several of the cells are clusters of thin, rod shaped Mycobacterium tuberculosis cells. The M tuberculosis cells are stained dark pink to purple in this slide. Individual bacterial cells cannot be clearly identified at this magnification. The bacterial cells are significantly smaller than the lung tissue cells, which are about 50 micrometers across.

A light micrograph of Clostridium tetani stained with malachite green endospore stain. There are numerous rod shaped cells arranged into chains and clusters. The cells are stained pink. Many of the cells contain a spherical endospore which is stained green. Each cell is about 3 micrometers in length and 0.5 micrometer in width. The endospores are each about 0.1 micrometer in diameter.

health equity

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is a dangerous infectious disease (caused by the pathogenic bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis) whose prevalence differs widely in different geographic regions; for example, the pathogen is carried by 28% of people in India but only 2.2% of people in the United States. Even within the United States, the incidence of tuberculosis cases differs remarkably among socioeconomic and racial groups. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the TB infection rate in Black Americans is eight times the rate in White Americans. This disparity between racial groups has persisted over decades in which the US population’s overall TB infection rate has declined. The CDC finds that causes of the disparity include barriers to accessing attentive health care; economic challenges leading to lack of health care coverage; cultural stigmas about the disease that impede people seeking medical care; and higher rates of comorbidities that increase TB susceptibility, such as diabetes and HIV infection.

How can the prevalence of tuberculosis in the nation’s Black population be reduced? The first priority, the CDC says, is education: teach the community and health care providers to recognize the symptoms of TB and to more readily consider the possibility of this diagnosis. In addition, Black patients need more economic support and social-worker assistance for the lengthy courses of therapy needed to eliminate the disease. These measures can increase health equity and help eliminate a deadly pathogen for us all.

SECTION SUMMARY