Learning Goal

Summarize the five stages of the scientific method.

Learning Goal

Summarize the five stages of the scientific method.

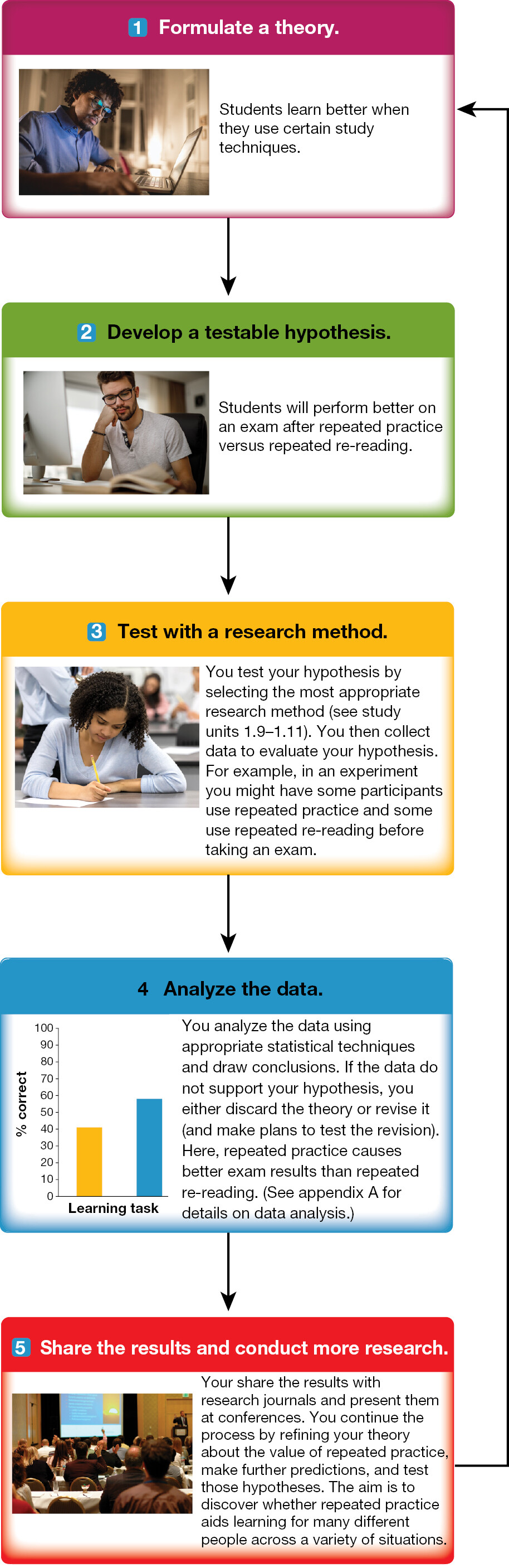

Box one is titled, Formulate a theory - Students learn better when they use certain study techniques. An accompanying image shows a boy sitting at a desk and writing, with a laptop open in front of him. Box two is titled Develop a testable hypothesis - Students will perform better on an exam after repeated practice versus repeated re-reading. An accompanying image shows a man sitting at a desk and reading a book. Box three is titled Test with a research method - You test your hypothesis by selecting the most appropriate research method. You then collect data to evaluate your hypothesis. For example, in an experiment you might have some participants use repeated practice and some use repeated re-reading before taking an exam. An accompanying image shows a girl taking an examination. Box four is titled, Analyze the data - You analyze the data using appropriate statistical techniques and draw conclusions. If the data do not support your hypothesis, you either discard the theory or revise it (and make plans to test the revision). Here, repeated practice causes better exam results than repeated re-reading. (See appendix A for details on data analysis.) An accompanying bar graph which compares the percentage of correctness of two learning tasks. One task is 40 percent correct, and the other task is 60 percent correct. Box five is titled, Share the results and conduct more research - Your share the results with research journals and present them at conferences. You continue the process by refining your theory about the value of repeated practice, make further predictions, and test those hypotheses. The aim is to discover whether repeated practice aids learning for many different people across a variety of situations. An accompanying image shows a man speaking at a seminar, presenting his research to the audience on a screen.

FIGURE 1.17 Five Steps in the Scientific Method

Psychologists systematically follow the five steps in the cycle of the scientific method to find objective information that pertains to their scientific goals. Shown here are the steps in the scientific method for research that investigates the effectiveness of repeated practice on learning for exams.

Across all types of psychological studies, psychologists may have one or more scientific goals for their research, including (1) describing what happens, (2) predicting when it happens, (3) controlling what causes it to happen, and (4) explaining why it happens. The systematic, empirical approach that psychologists use to achieve these goals is called the scientific method. The process of the scientific method includes the continuous cycle of five steps shown in Figure 1.17 on page 26. The scientific method is so important in conducting psychological research that you will revisit it throughout the book in the Methods of Psychology feature. To explore each step in more detail, suppose you have decided to conduct research to determine which study techniques best help people learn new information.

Step 1: Formulate a Theory Psychologists study research questions that they find interesting. When they encounter a puzzling question about how people think, feel, or act, they seek to understand that process. To answer your question about the best study techniques, you will need to know the study methods that students use and how effective they are. You will also need to formulate a theory (Figure 1.17, Step 1). A theory is an explanation of how some mental process or behavior occurs. The theory consists of interconnected ideas or concepts that explain prior research findings and make predictions about future events.

To formulate your theory, you need to learn about prior research related to the topic. You should start by performing a literature review in which you explore the scientific articles related to your ideas. Many resources are available to assist with literature reviews, including Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com/), the American Psychological Association’s PsycInfo (https://www.apa.org/pubs/databases/psycinfo), and a government database called PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). You can search these databases by asking questions related to your research question, such as “How do students prefer to study?” Or you might search keywords and phrases related to the topic, such as “repeated practice.” The results of your searches will reveal whether other scientists have already investigated similar topics.

The findings of prior research will help you refine your theory and guide the direction of your study. A clearly stated theory is important because it is the basis for Step 2 of the scientific method. In this case, let’s use information from this chapter and state your theory as “Students learn better by repeated practice than by rereading information.”

Step 2: Develop a Testable Hypothesis Once you have a theory, you need to state your hypothesis, which is a specific, testable prediction about what should be observed if the theory is accurate (Figure 1.17, Step 2). Any one theory is usually tested by several separate hypotheses across different studies. Every hypothesis tests an aspect of the theory by targeting one of the four goals of science listed above: describing, predicting, controlling, and explaining.

For example, your research may have the goal of simply describing something, such as what study techniques students use or what techniques they think are best. Or your goal may be to predict a relationship between two things, such as exam scores based on how much time students spend using certain study methods. As another possibility, your goal may be to control factors that affect an outcome, such as students’ study methods, to explain which form of studying yields higher exam scores. Each of these different goals will lead you to develop a different testable hypothesis that is specific to that goal. For example, a good hypothesis for the goal of controlling students’ studying to explain which study technique leads to better outcomes might be “Students will perform better on an exam after repeated practice with information than they will after repeated reading of the information.”

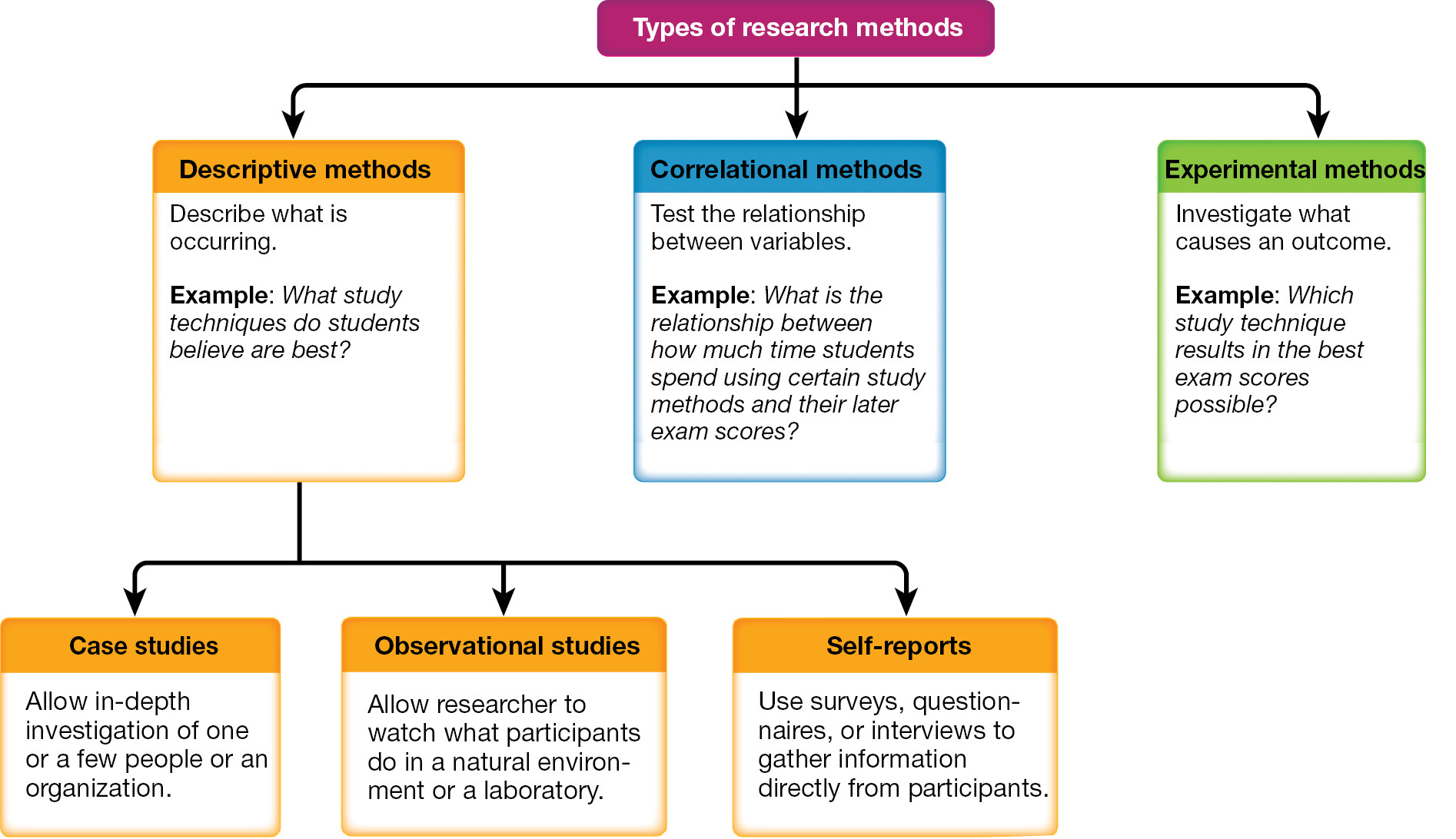

Step 3: Test With a Research Method After you have stated a clear hypothesis, you move to the third step in the scientific method, in which you choose the research method to test your hypothesis (Figure 1.17, Step 3). The three main types of research methods you can use are descriptive, correlational, and experimental (Figure 1.18), which are explained in detail later in this chapter.

The first box is types of research methods with 3 boxes coming out of it. The boxes are, Descriptive methods: Describe what is occurring (Example: What study techniques do students believe are best?), Correlational methods: Test the relationship between variables (Example: What is the relationship between how much time students spend using certain study methods and their later exam scores?), and Experimental methods: Investigate what causes an outcome (Example: Which study technique results in the best exam scores possible?). There are three boxes coming from descriptive methods, which are observational studies (allow researcher to watch what participants do in a natural environment or a laboratory), self-reports (use surveys, questionnaires, or interviews to gather information directly from participants), and case studies (allow in-depth investigation of one or a few people or an organization.

FIGURE 1.18 Three Main Types of Research Methods

In Step 3 of the scientific method, psychologists choose which of three main research methods are most appropriate for meeting their research goals and testing the hypothesis they stated in Step 2. For each of the three main research methods, you see an example of a study that could use that research method to investigate the effectiveness of study techniques.

The most appropriate research method depends on the goal of your research and your hypothesis. For example, if your goal and hypothesis are related to describing something, such as which study techniques students think are best, then you should use descriptive methods (see Figure 1.18, orange boxes). However, if the goal and hypothesis refer to predicting a relationship between two things, such as how much time students spend using certain study techniques and their exam scores, then you should use the correlational method (see Figure 1.18, blue box). If your goal and hypothesis are about controlling what causes an outcome, such as how study techniques affect exam scores, then you need to use the experimental method (see Figure 1.18, green box). The research method you use also depends on how much control you need over manipulating and measuring certain factors in the study. Each factor, called a variable, is something in the world that can vary and that the researcher can manipulate (change), measure (evaluate), or both. You will learn about two types of variables in study unit 1.11.

Let’s look at the variables for your experiment. There is a variable you will manipulate and a variable you will measure. Your hypothesis indicates that you will manipulate the variable of what study technique students use. Half of your participants will engage in repeated reading, in which they read a passage and then reread it two more times before they take an exam on the material. The other half of your participants will read the material and repeatedly practice with it on two practice tests before taking an exam on the material. To determine whether there is a cause/effect relationship between the study technique and exam scores, you must try to control for other factors, such as the students’ academic abilities. To do so, you randomly assign each student to use one of the study techniques. Doing so will help ensure that students’ overall grade point average (GPA) is similar in each group and that neither group has better students. In your experiment, the variable that you measure is the participants’ performance on a later exam. A difference in exam scores across participants who used different study techniques will suggest whether one study technique was more effective than the other.

Step 4: Analyze the Data In Step 4 of the scientific method you analyze the data from your research to see whether the results support your hypothesis (Figure 1.17, Step 4). First you summarize the raw data. Then you mathematically determine whether differences really exist between the different sets of summarized data. Both of these forms of data analysis are described in Appendix A. In our example, you could summarize your data by comparing performance to see which group scored higher on the exam: students who repeatedly read or repeatedly practiced. Next, you must decide whether any differences between these conditions were meaningful. That is, you must decide whether they are a result of the factor of interest: study technique. In other words, you must determine whether you found a significant effect. In this case, you might find a significant effect if the exam scores of the students who repeatedly practiced are higher than the exam scores of those who repeatedly read the passage. This result would suggest that repeated practice is a better study method in general.

Unfortunately, some psychologists alter their hypothesis based on their data analysis. This practice is highly discouraged because it is easy to come up with explanations for data after the fact, but there is little confidence that your explanation is correct because the research was not designed to explore this new explanation. For these reasons, researchers should document their hypotheses and methods before they start collecting and analyzing data (Lindsay, 2017; Vazire, 2018).