LEARNING GOAL

Summarize the five stages of language development.

LEARNING GOAL

Summarize the five stages of language development.

As you learned in the chapter opener, Brooke Greenberg’s physical and mental development stopped when she was a toddler. At age 19, Brooke could communicate only by making infant-like sounds. The ability to speak in sentences develops as the brain changes and as cognitive abilities become more sophisticated. As children develop social skills, they also improve their language abilities. Thanks to language, we can live in complex societies where our ability to communicate helps us learn the history, rules, and values of our culture.

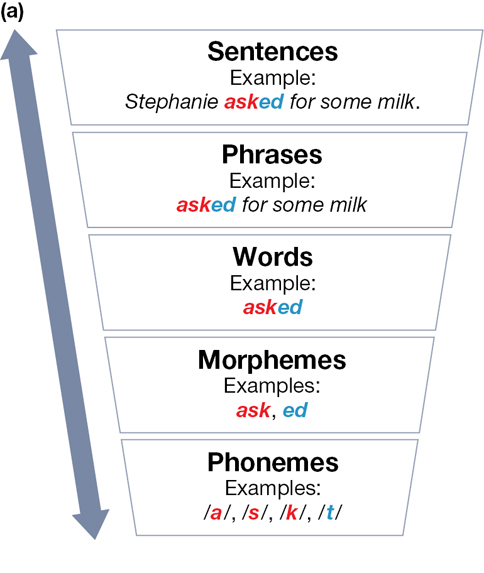

Language is a system of using sounds and symbols according to grammatical rules. It can be viewed as a hierarchical structure. Sentences can be broken down into smaller units, called phrases, and phrases can be broken down into words (Figure 4.20a). Each word consists of one or more morphemes, which are the smallest units that have meaning, including suffixes and prefixes. Each morpheme consists of one or more phonemes or basic sounds (Figure 4.20b). For example, the word asked has two morphemes (“ask” and “ed”) and four phonemes (the sounds you make when you say the word: /a/s/k/t/). Syntax is the system of rules about how words are combined into phrases and how phrases are combined to make sentences. For example, English syntax dictates that we say Stephanie asked for some milk, not Stephanie some milk for asked.

In the image, the hierarchy of language chart is shown from largest at the top to smallest at the bottom. Each one has an example based on the word asked with ask in red and e d in blue. All other words are in black. The biggest unit of language is a sentence. The example given for sentences is, that Stephanie asked for some milk. The next unit of language phrases with the example asked for some milk. The next unit of language is words and the example is asked. The next unit of language is morphemes and the example is ask, e d. The smallest unit of language is phonemes and examples are the individual sounds, a, s, k, and t.

The photo shows two young children pointing to words that are made from construction paper on the wall. Both of the children are pointing to the word crying.

FIGURE 4.20 Organization of Language

(a) Language is organized hierarchically. Sentences and phrases are created from words, words are created from morphemes, and morphemes are created from phonemes. (b) In learning to read, these children are combining phonemes into morphemes.

How did you develop your remarkable ability to use language?

Five Stages of Language Development Infants are born ready to learn language. In fact, the language or languages that mothers speak during pregnancy influence newborns’ listening preferences. For instance, Canadian newborns whose mothers spoke only English during pregnancy showed a strong preference for sentences in English as compared with sentences in Tagalog, a major language of the Philippines. Newborns of mothers who spoke both Tagalog and English during pregnancy paid attention to both languages (Byers-Heinlein et al., 2010). Further, up to 6 months of age, a baby can distinguish all the speech sounds that occur in all languages, even if the sounds do not occur in the language spoken in the baby’s home (Kuhl, 2007; Kuhl et al., 2003; Kuhl et al., 2006).

From hearing sounds immediately after birth and then learning the sounds of their own languages, babies develop the ability to speak. Without working very hard at it, humans appear to go from babbling as babies to employing a full vocabulary of about 60,000 words as adults. Learning to speak follows a distinct path. During the first months of life, newborns’ actions—crying, fussing, eating, and breathing—generate all their sounds. In other words, in the first stage of language development, called cooing, babies’ first verbal sounds are cries, gurgles, grunts, and breaths. During this first stage, from 3 to 5 months, they begin to coo and laugh. In the second stage, they begin babbling, which is intentional vocalization that does not have a specific meaning. Between 5 and 7 months, their babbling includes using single consonants and vowels. From 7 to 8 months, they babble in syllables (ba-ba-ba, dee-dee-dee).

Between the ages of 8 and 18 months, but usually by the end of their first year, infants around the world are usually saying their first words. Coaching by parents helps children develop language (Ferjan Ramirez et al., 2020). During this third stage in language development, the one-word stage, toddlers typically combine phonemes into morphemes to label items in their environment (kitty, milk), simple action words (go, up, sit), quantifiers (all gone! more!), qualities or adjectives (hot), socially interactive words (bye, hello, yes, no), and even internal states (boo-boo after being hurt; Pinker, 1984). Thus even very young children use words to perform a wide range of communicative functions. They name, comment, and request.

By about 18 to 24 months, in the fourth stage of language development, children’s vocabularies start to grow rapidly. They put words together and form basic sentences of roughly two words. Though these mini-sentences are missing some words, they have syntax. Typically, the word order indicates what has happened or should happen: For example, “Throw ball. All gone” translates as I threw the ball, and now it is gone. The psychologist Roger Brown called these utterances telegraphic speech because the children speak as if they are sending a telegram. They put together bare-bones words according to correct syntax (Brown, 1973).

As children use language in increasingly sophisticated ways, they sometimes overapply regular grammar rules. This tendency, in the fifth stage of language development, is called overregularization and is seen between the ages of about 3 and 5 years old. For example, when children learn that adding –ed makes a verb past tense, they add –ed to every verb, even verbs that do not follow that rule. Thus they may say “runned” or “holded” even though they may have said “ran” or “held” at a younger age. This stage usually lasts through the early elementary school years, when children begin to master irregular forms of words. Such overregularizations reflect an important aspect of language acquisition: Children are not simply repeating what they have heard others say. After all, they most likely have not heard anyone say “runned.” Instead, these errors occur because children recognize patterns in spoken grammar and then apply the patterns to new sentences they never heard before (Marcus, 1996). Of course, as children gain experience using language with other people, they usually learn to correct these mistakes. By about age 6, children use language nearly as well as most adults. Their vocabulary will continue to grow throughout their lives.

![]() Language Development Demonstration

Language Development Demonstration

IMPACT LEARNING PAUSE

Are You Monitoring?

Have you made a bad decision about studying? Monitoring can lead to better choices. Use self-regulated learning to study the best way.

LEARNING GOAL CHECK: REVIEW