THE MANY-TRAIT APPROACH

It can be interesting and useful to explore one trait in depth, as we just saw. However, some personality psychologists—including me—enjoy looking at many traits at once (Sherman & Serfass, 2015). Several lists have been developed for this purpose, including Allport and Odbert’s (1936) famous list of 17,953, which is too long to be useful. Another list has 504 trait adjectives—still an awful lot—organized into 61 clusters (D. Wood, Nye, & Saucier, 2010). For the present, my favorite remains the list of 100 personality traits called the California Q-Set (Bem & Funder, 1978; J. Block, 1961/1978).

The California Q-Set

Maybe trait is not quite the right word for the items of the Q-set. The set consists of 100 phrases. Traditionally, they were printed on separate paper cards; now they are sorted on a computer screen. Each phrase describes an aspect of personality that might be important for characterizing a particular individual. For example, Item 1 reads, “Is critical, skeptical, not easily impressed”; Item 2 reads, “Is a genuinely dependable and responsible person”; Item 3 reads, “Has a wide range of interests”; and so forth, for the remaining 97 items (see Table 5.1 for more examples).

Table 5.1 SAMPLE ITEMS FROM THE CALIFORNIA Q-SET

|

1. |

Is critical, skeptical, not easily impressed |

|

2. |

Is a genuinely dependable and responsible person |

|

3. |

Has a wide range of interests |

|

11. |

Is protective of those close to him or her |

|

13. |

Is thin-skinned; sensitive to criticism or insult |

|

18. |

Initiates humor |

|

24. |

Prides self on being “objective,” rational |

|

26. |

Is productive; gets things done |

|

28. |

Tends to arouse liking and acceptance |

|

29. |

Is turned to for advice and reassurance |

|

43. |

Is facially and/or gesturally expressive |

|

51. |

Genuinely values intellectual and cognitive matters |

|

54. |

Emphasizes being with others; gregarious |

|

58. |

Enjoys sensuous experiences—including touch, taste, smell, physical contact |

|

71. |

Has high aspiration level for self |

|

75. |

Has a clear-cut, internally consistent personality |

|

84. |

Is cheerful |

|

98. |

Is verbally fluent |

|

100. |

Does not vary roles; relates to everyone in the same way |

Source: Adapted from J. Block (1961/1978), pp. 132–136.

More information

A black and white photo shows a man sitting at a table arranging cards in front of him.

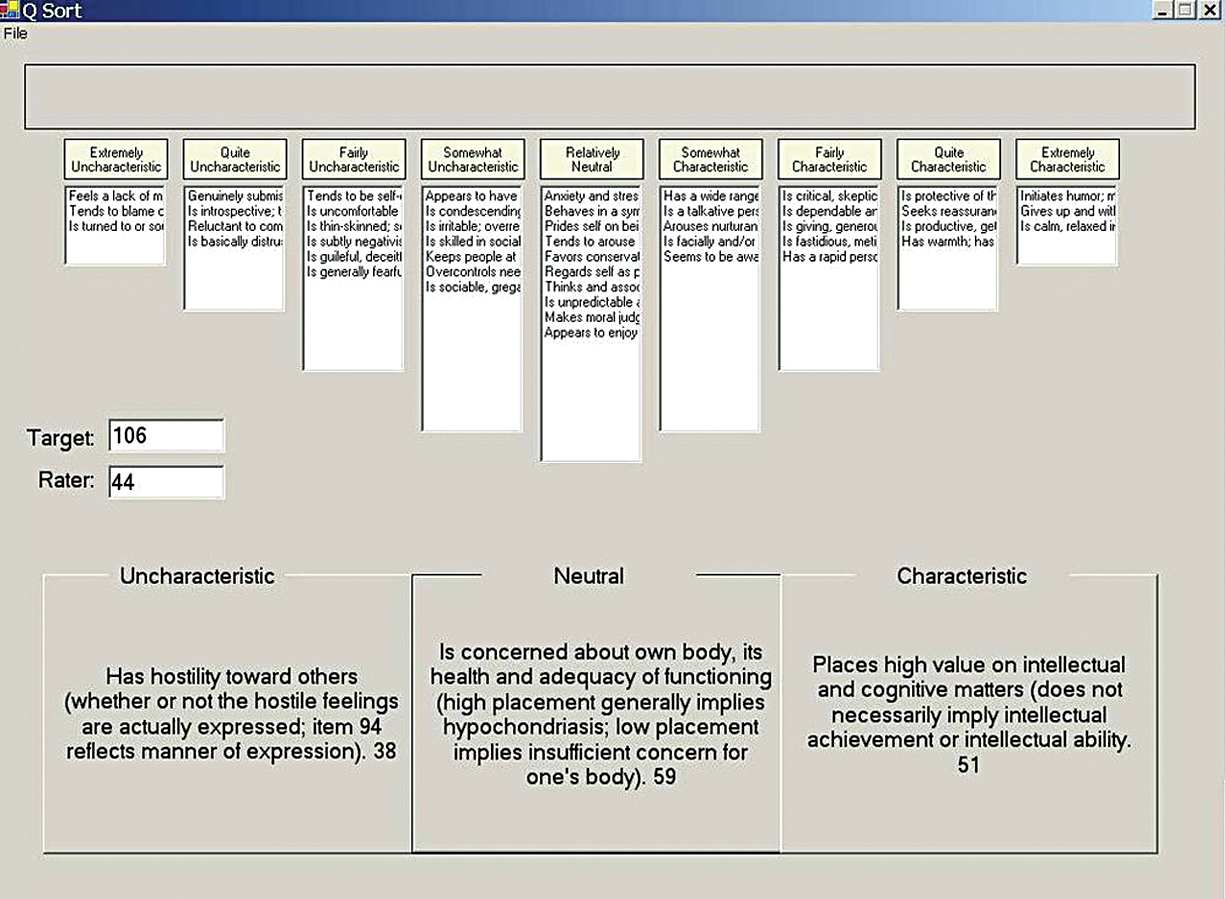

Both the way this list of items is used and its origin are rather unusual. Raters express judgments of personality by sorting the items into nine categories ranging from highly uncharacteristic of the person being described (Category 1) to highly characteristic (Category 9). Items neither characteristic nor uncharacteristic are placed in or near Category 5. The distribution is forced, which means that a predetermined number of items must go into each category. The usual Q-sort distribution is peaked, or “normal,” meaning that most items are placed near the center and only a few (just 5 of the 100) can be placed on each end (Figures 5.4 and 5.5).

The rater who does the sorting might be an acquaintance, a researcher, or a psychotherapist; in these cases, the item placements constitute I-data. Alternatively, a person might provide judgments of one’s own personality, in which case the item placements constitute S-data. The most important advantage of Q-sorting is that it forces the judge to compare all of the items directly against each other. Furthermore, the judge is restricted to identifying only a few items as being most important. Nobody can be described as all good or all bad; there simply is not enough room to put all the good traits—or all the bad traits—into Categories 9 or 1. Finer and subtler discriminations must be made.

More information

A screenshot displays a virtual version of the Q-Sort test. A series of text boxes from left to right read: extremely uncharacteristic, quite uncharacteristic, fairly uncharacteristic, somewhat uncharacteristic, relatively neutral, somewhat characteristic, fairly characteristic, quite characteristic, extremely characteristic. Below each label is are text boxes filled with text that is descriptive of personality and behavioral traits of a person. Target is marked as 106 and Rater is marked as 44. Three boxes at the bottom of the screenshot are labeled uncharacteristic, neutral, and characteristic with additional descriptive text.

The items of the California Q-Set were not derived through a formal, empirical procedure. Rather, a team of researchers and clinical practitioners sought to develop a comprehensive set of terms sufficient to describe the people they interacted with every day (J. Block, 1961/1978). After formulating an initial list, the team met regularly to use the items to describe their clients and research participants. When an item proved useless or vague, they revised or eliminated it. When the set was insufficient to describe some aspect of a particular person, they wrote a new item. Later, other investigators further revised the Q-set so that its sometimes technical phrasing could be understood and used by nonpsychologists; this slightly reworded list is excerpted in Table 5.1 (Bem & Funder, 1978). The 100 items of the California Q-Set have been used to study a wide range of topics, including (to select two) talking and political beliefs.

Talking

People talk (and write) all day long. For example, have you ever noticed that some people often use words such as “absolutely,” “exactly,” and “sure,” while others hardly ever do? Does this imply anything about their personalities?

More information

A selfie of college psychologist Lisa Fast.

A study by my former graduate student (and now professor) Lisa Fast (Figure 5.6) and I used the Q-sort and its “many-trait approach” to address this question (Fast & Funder, 2008). Each of our participants underwent a 1-hour life-history interview that ranged over past experiences, current activities, and future prospects. The interview was recorded, and then the questions were deleted, leaving just the participants’ answers. Then these answers were transcribed into computer files containing the thousands of words used by each participant. Finally, the word files were analyzed by a computer program called “LIWC” (Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count; Pennebaker et al., 2001). The program calculates the number of words that appear in each of a long list of categories. We also gathered personality ratings of each participant from people who knew them well (I-data; see Chapter 2), using the 100-item Q-sort described above.4 Of course, these informants had not been present during the life-history interview; they could base their ratings only on what they had observed during daily life with the participants.

One category counted by the LIWC program is “certainty words,” which include (among others) “absolutely,” “exact,” “guarantee,” “sure,” and “truly.” Who uses words like these when chatting about their life history? Perhaps these are people who are sure of themselves. Or they might be people who are acting confidently to cover up their insecurity. Since both possibilities seem plausible, we need to look at the data.

So, consider the findings summarized in Table 5.2. Not all of the Q-sort personality items were significantly correlated with word use, but many of them were (the table is a partial list). People who used a relatively large number of certainty words were described by their acquaintances as (among other attributes) intelligent, verbally fluent, the kind of person who is turned to for advice, ambitious, and generous. People who used such words relatively rarely were more likely to be described as emotionally bland, exploitative, and “repressive” (which means they tend to avoid recognizing unpleasant facts). And remember: The acquaintances who made these personality ratings were not present at the interview, so if they had ever heard the participant using certainty words, it was in real life, not in the lab.

Table 5.2 PERSONALITY CORRELATES OF USING “CERTAINTY” WORDS IN A LIFE-HISTORY INTERVIEW

|

Informants’ Q-Item Description |

Correlation With Certainty Word Use |

|

Positive Correlates |

|

|

High intellectual capacity |

.26 |

|

Verbally fluent |

.25 |

|

Is turned to for advice and reassurance |

.22 |

|

Has high aspiration level for self |

.21 |

|

Concerned w/own body and its physiological functioning |

.21 |

|

Behaves in a giving manner to others |

.20 |

|

Behaves in an assertive fashion |

.20 |

|

Straightforward and candid |

.19 |

|

Negative Correlates |

|

|

Is emotionally bland |

−.23 |

|

Creates and exploits dependency |

−.21 |

|

Repressive and dissociative tendencies |

−.19 |

Note: All correlations are significant at p < .01. Examples of certainty words include “absolutely,” “exact,” “guarantee,” “sure,” and “truly.”

Source: Adapted from Fast & Funder (2008), p. 340.

Do these results tell us anything about the psychological meaning of using certainty words? You can come to your own conclusion. My own answer would be yes, to an extent. It does seem like people who use such words are not simply covering up their own insecurity. Overall, they appear to be smart and functioning well. But not quite all of the traits are consistent with this pattern. Why did people who were “concerned with own body and its physiological functioning” use more certainty words? I have absolutely no idea. So, while the overall pattern seems fairly clear, not everything completely fits. This is a typical result of research using the many-trait approach. Looking at the whole pattern is probably more informative than paying a lot of attention to occasional inconsistencies, which might, after all, just be due to chance.

Political Beliefs

Political beliefs might be the last thing you would expect to be related to one’s personality as a child. Well, you would be wrong. Psychologists Jack and Jeanne Block assessed the personalities of a group of children in nursery school (J. Block & Block, 2006a, 2006b). Almost 20 years later, the same children, now grown up,5 completed a measure of their political beliefs. The measure included questions about abortion, welfare, national health insurance, rights of criminal suspects, and so forth. Each individual earned a score along a dimension from “liberal” to “conservative.” This score turned out to have a remarkable set of personality correlates reaching back in time. Children who grew into political conservatives were likely to have been described almost 20 years earlier as tending to feel guilty, as anxious in unpredictable environments, and as unable to handle stress well. Those who grew into liberals, by contrast, were more likely to have been described years earlier as resourceful, independent, self-reliant, and confident.

What do these findings mean? One hint may come from the work of a group of psychologists (Adorno et al., 1950) who wrote a book called The Authoritarian Personality, a classic of psychological research that culminated in the California F scale (F meaning “fascism”). This scale aimed to measure the basic antidemocratic psychological orientation that these researchers believed to be the common foundation of anti-Semitism, racial prejudice, and political pseudoconservatism, which they viewed as a pathological mutation of true (and nonpathological) political conservatism.

More than 50 years after the concept was introduced, research on authoritarianism and related concepts continues at a steady pace, with more than 4,000 articles and counting.6 Research since the time of the classic studies has shown that authoritarians tend to be uncooperative and inflexible when playing experimental games, and they are relatively likely to obey an authority figure’s commands to harm another person (Elms & Milgram, 1966). They experience fewer positive emotions (Van Hiel & Kossowska, 2006), are likely to oppose equal rights for transgender individuals (Tee & Hegarty, 2006), and, if they are Americans, tended to favor the 2003 American military intervention in Iraq (Crowson et al., 2005). Authoritarians also watch more television (Shanahan, 1995)!7

Research has explored the idea that authoritarians, deep inside, are afraid, and their attitudes stem from an attempt to lessen this fear. When authoritarians feel their standard of living is declining, that crime is getting worse, and that environmental quality is declining, they become more likely to favor restrictions on welfare and eight times more likely to support laws to ban abortions (Rickert, 1998). When society is in turmoil and basic values are threatened, authoritarians become particularly likely to support “strong” candidates for office who make them feel secure, regardless of the candidate’s party (McCann, 1990, 1997). Indeed, even communists can be authoritarian. A study conducted in Romania 10 years after the collapse of communist rule found that people who scored high on authoritarianism still believed in communist ideas (such as government ownership of factories), but also supported fascist political parties and candidates whose positions were at the opposite extreme (Krauss, 2002). The common thread seemed to be that the personalities of these people led them to crave strong leaders. They rather missed their communist dictators, it seemed, and wouldn’t have minded substituting strong, fascist dictators instead of seemingly weak, democratic politicians.

The connection between fearfulness and this kind of pseudoconservatism (not actual conservatism) might help explain the connection between childhood personality and adult political beliefs found by the Blocks. As they wrote:

Timorous conservatives of either gender will feel more comfortable and safer with already structured and predictable—therefore traditional—environments; they will tend to be resistant to change toward what might be self-threatening and forsaking of established modes of behavior; they will be attracted by and will tend to support decisive (if self-appointed) leaders who are presumed to have special and security-enhancing knowledge. (J. Block & Block, 2006a, p. 746)

Liberals, by contrast, are motivated more by what the Blocks call “undercontrol,” a desire for a wide range of gratifications soon. They seek and enjoy the good life, which is perhaps why so many of them drive brand-new Subarus and sip excellent Chardonnays.8 As a result,

Various justifications, not necessarily narrowly self-serving, will be confidently brought forward in support of alternative political principles oriented toward achieving a better life for all. Ironically, the sheer variety of changes and improvements suggested by the liberal-minded under-controller may explain the diffuseness, and subsequent ineffectiveness, of liberals in politics where a collective singlemindedness of purpose so often is required. (J. Block & Block, 2006a, p. 746)

Longitudinal research like that of the Blocks, wherein the same people are followed and measured repeatedly from childhood to adulthood, is still much too rare (see Chapter 6), and no finding really should be trusted until it’s been replicated, as discussed in Chapter 3. But in the present case, I have some good news to report. A large longitudinal study attempted to replicate the findings just summarized and largely succeeded. Not only did the later study—with a large sample of 708 children and their parents—obtain similar results, but it also shed new light on what might be going on (Fraley et al., 2012). It turns out that the children with early emotional difficulties such as described by the Blocks were likely to have parents who themselves scored high on authoritarianism. Thus, the later political beliefs of their children might be associated with these early emotional traits, but could also be a direct result of absorbing the outlook of their parents and perhaps even genetic similarity. Two more even larger studies (with more than 8,700 participants each) conducted in the United Kingdom also confirmed that early childhood personality is associated with later political beliefs (Lewis, 2018). Children described at age 5 or 7 as anxious, misbehaved, and hyperactive grew up to be adults who were discontented with the economic and political system.

Although research on the personality correlates of political beliefs is fascinating, much of it leads to conclusions of the sort that should make you wary. Most psychologists are political liberals and so have a built-in readiness to conclude that conservatives are flawed in some way.9 Would research done by a conservative psychologist—if you could find one—reach the same conclusion?

Although research on the personality correlates of political beliefs is fascinating, much of it leads to conclusions of the sort that should make you wary.

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt has suggested that, rather than focus on the character flaws of people on one or the other side of an ideological divide, it might be more fruitful to understand how they favor different but equally defensible values (Haidt, 2008). His research shows that liberals and conservatives alike endorse values he calls harm/care (kindness, gentleness, nurturance) and fairness/reciprocity (justice, rights, and fair dealing). However, conservatives are also likely to strongly favor three other values that liberals regard as less important: in-group loyalty (taking care of members of one’s own group and staying loyal), authority/respect (following the orders of legitimate leaders), and purity (living in a clean, moral way). These differences in values help to explain, for example, why conservatives in the United States get upset seeing someone burn an American flag, whereas liberals are more often baffled about why anybody would think it’s a big deal.

Haidt’s argument provides a useful counterpoint to the usual assumptions of political psychology, which sometimes come uncomfortably close to treating conservatism as a pathology (Jost et al., 2003). But it is not clear how far it can go toward explaining findings such as the childhood predictors and adult personality correlates of adult conservatism. These remain data that need to be accounted for. The next few years promise to be an exciting time at the intersection of politics and personality, both because more data and theory are coming out of psychological research, and because rapidly changing events are altering the context in which we think about politics.

Glossary

- California Q-Set

- A set of 100 descriptive items (e.g., “is critical, skeptical, not easily impressed”) that comprehensively covers the personality domain.

Endnotes

- As you can tell, this project was a lot of work.Return to reference 4

- Sort of.Return to reference 5

- Instead of the classic F scale, current research more often uses a measure of “right-wing authoritarianism” (RWA) developed by Canadian psychologist Robert Altemeyer (1998).Return to reference 6

- The research didn’t say which channel, but do you want to guess?Return to reference 7

- This is my observation, not the Blocks’.Return to reference 8

- Personally, I often feel that there is something wrong with the people who disagree with me. Don’t you?Return to reference 9