5 TRAITS AND TYPES: THE BIG FIVE AND BEYOND

More information

A photo shows a group of young women sitting together. The one in the middle is drinking from a cup as one of the others leans against her legs.

TRAITS EXIST and can be assessed by psychologists as well as by everybody else in daily life (Chapter 4). But what are they really? Let’s begin the answer with a reminder of what traits are not. They are not the determinants of what people do at all times and in all situations; an extravert isn’t always extraverted, an agreeable person isn’t always agreeable, and an anxious person isn’t even always anxious. As discussed in Chapter 4, what traits characterize best is a person’s average behavior over time and across situations. An extraverted person will generally behave in a much more active, sociable manner than will an introverted person when averaged across every action every day for two weeks, for example. But that doesn’t mean that the introverted person never acts in an active, sociable way, just not so often as an extraverted person (Fleeson & Law, 2015).

An extravert isn’t always extraverted, an agreeable person isn’t always agreeable, and an anxious person isn’t even always anxious.

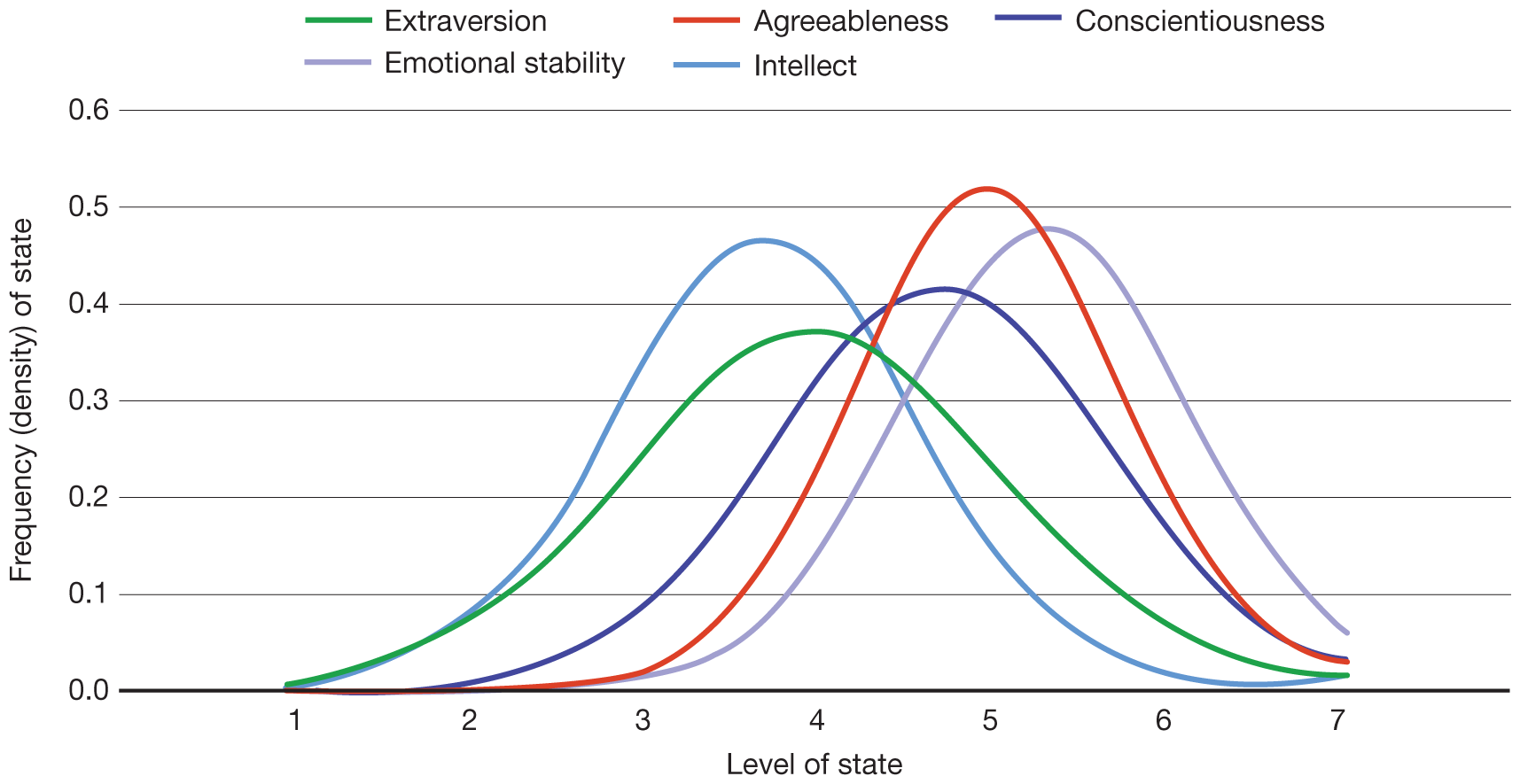

The truth of the matter is even subtler than that. There will be times when the introverted person actually acts in a more extraverted manner than the person who is usually more extraverted. The same is true of the difference between two people who differ in their level of anxiety; the more anxious person feels that way more often than the less anxious person, but at some times or in some circumstances the person who is classified as less anxious might actually feel more anxiety than the person classified as less anxious, and vice versa. The psychologist Will Fleeson (2001) describes this difference as contrasting “density distributions” of behaviors and states, as illustrated in Figure 5.1.

More information

A graph shows the frequency of behaviors and emotional states associated with five personality traits over a two-week period. The x-axis is labeled “Level of State” and ranges from 1 to 7. The y-axis is labeled “Frequency (density) of state and ranges from 0.0 to 0.6. Five bell curves are shown in different colors representing the following traits: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and intellect. The expression of all traits spanned almost the entire 7-point scale with extraversion peaking at .38, agreeableness peaking at .51, conscientiousness peaking at .41, emotional stability peaking at .48, and intellect peaking at .47. Values are approximated.

Source: Fleeson (2001).

But even though people who differ in extraversion, anxiety, and other traits do not necessarily act in accordance with their usual personality all the time, such differences can be and often are large enough to have important effects on how their lives turn out. This is because even small effects of personality on behavior “aggregate” or accumulate over time. As explained in Chapter 4, personality is the baggage you always have with you.

The purpose of this chapter is to take a closer look at personality traits and types and how they are studied. The following chapter will consider how personality develops and changes over the lifetime.

Research that seeks to connect personality with behavior uses four basic methods: the single-trait approach, the many-trait approach, the essential-trait approach, and the typological approach.

More information

A diagrams depicts how traits lead to predicted behaviors. On the left there is a circle containing the word “Trait”. From this circle there are six arrows pointing to the right, each leading to a rectangle containing the word “Behavior”.

The single-trait approach (Figure 5.2) examines the link between personality and behavior by asking, What do people like that do? (“That” refers to a [hopefully] important personality trait.) Some traits have seemed so important that psychologists have tried to assess as many of their implications as possible. For example, extensive research programs have examined self-monitoring and narcissism, to name only two.

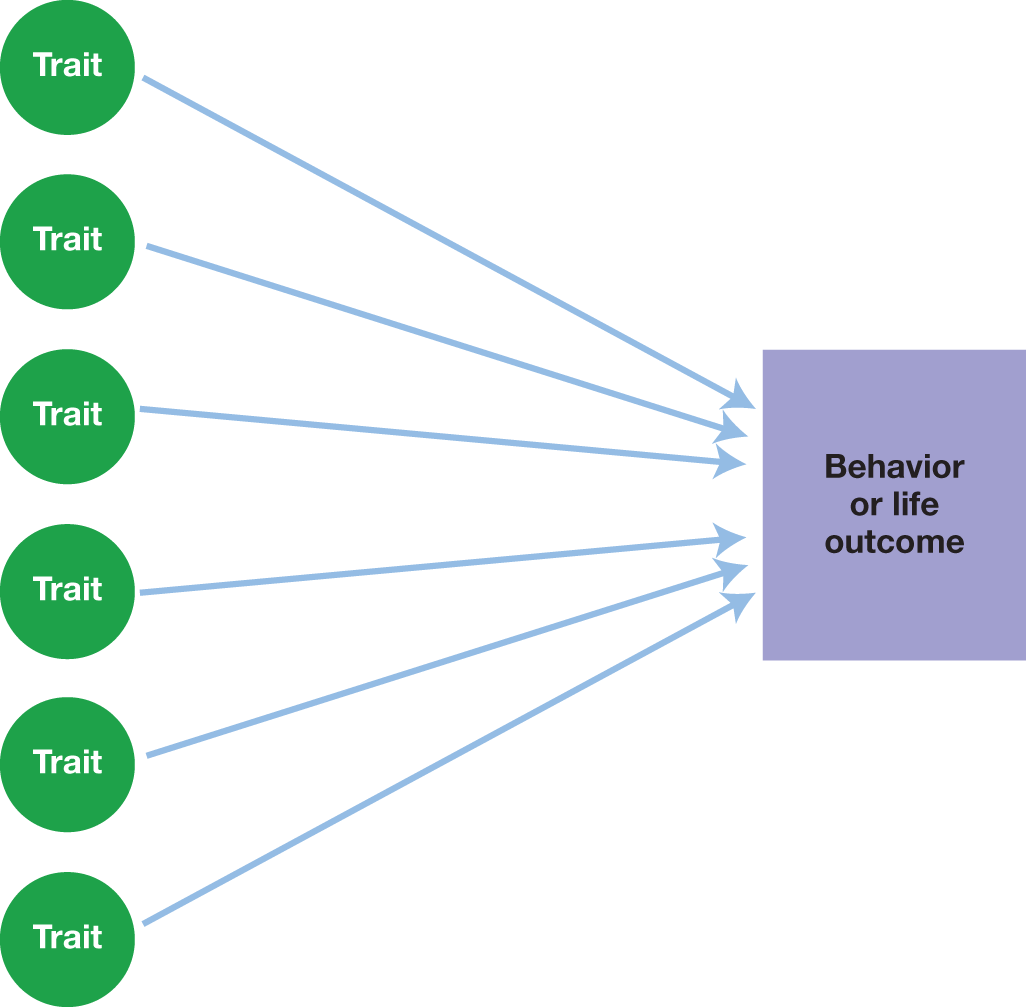

The many-trait approach (Figure 5.3) works from the opposite direction, beginning with the (implicit) research question, Who does that? (where “that” is an important behavior). Researchers attack the behavior of interest with long lists of traits intended to cover a wide range. They determine which traits correlate with the specific behavior and then seek to explain the pattern of correlations. A researcher might count the number of times that participants use a certain kind of word during an interview and also measure up to 100 traits in each participant. The researcher can then see which of these traits tend to characterize the participants who talk that way. The goal is to illuminate how personality is reflected in language.

More information

A diagram depicts how traits lead to a single behavior or life outcome. On the left there are 6 circles with the word “Trait” in the middle of each. From each circle there is an arrow leading to a rectangle on the right that reads, “Behavior or Life Outcome.”

The essential-trait approach addresses the difficult question, Which traits are the most important? As Allport’s hardworking assistant Odbert learned the hard way (Chapter 4), the dictionary includes literally thousands of traits.1 This embarrassment of riches has led to confusion about which ones really are important enough to be measured and studied. Certainly not all of them! The essential-trait approach, which has made considerable headway over the years, tries to narrow the list to those that really matter. Most prominently, the Big Five list includes the traits of extraversion, neuroticism, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness (John et al., 2008).

But does it really make sense to array everybody in the world along the various trait scales that psychologists have developed? Even psychologists have sometimes wondered. The typological approach stems from a doubt and a hope. The doubt is whether it is really valid to compare people with each other quantitatively on the same trait dimensions. Perhaps because people are so qualitatively different comparing their individual trait scores makes as little sense as the proverbial comparison between apples and oranges. The hope is that researchers can identify groups of people who both resemble each other enough and are at the same time different enough from everybody else that it makes sense to treat them as if they belong to the same “type.” Instead of focusing on traits directly, this approach focuses on the patterns of traits that characterize whole persons and tries to sort these patterns. One widely used measure of personality types is particularly questionable, as we shall see. But overall, thinking of people in terms of types, while far from ideal, can be useful for some purposes.

Glossary

- single-trait approach

- The research strategy of focusing on one particular trait of interest and learning as much as possible about its behavioral correlates, developmental antecedents, and life consequences.

- many-trait approach

- The research strategy that focuses on a particular behavior and investigates its correlates with as many different personality traits as possible in order to explain the basis of the behavior and to illuminate the workings of personality.

- essential-trait approach

- The research strategy that attempts to narrow the list of thousands of trait terms into a shorter list of the ones that really matter.

- typological approach

- The research strategy that focuses on identifying types of individuals. Each type is characterized by a particular pattern of traits.

Endnotes

- Odbert worked with an English dictionary, and English does seem to have an unusually large number of trait terms. Still, it appears that words that refer to personality traits can be found in every language (see Chapter 12).Return to reference 1