THE GEOGRAPHIES OF SOUND

In this chapter, we have heard fourteen musical examples taking us through many different aspects of the characteristics of musical sound and the ways in which they combine to constitute musical forms. Along the way, we have traveled great distances, hearing music from the Canadian Arctic, several regions of Africa, sites in the Caribbean, East and Southeast Asia, and many other places as well.

Chapter 1 has set the stage for a central goal of Soundscapes: to explore the widest range of musics in comparative perspective. In the following chapters, we will delve into music from many different places that provide different perspectives on the same theme, whether it be the manner in which music and musicians migrate, to the importance of dance, or to the ubiquity of music and ritual in everyday life.

INDIVIDUAL PORTRAITS |

|

PAULINE OLIVEROS’S “DEEP LISTENING” |

Few people devote more time to thinking about how to listen than composers. Composer Pauline Oliveros has devoted her life to exploring the listening process. Throughout her career, she has united the processes of composition and performance. Oliveros says that “composition gives you time to change your mind, while improvisation provides an edge where what you do is it. I do both. I like collaboration and enjoy opportunities to work with different people from diverse communities.” Oliveros further composes and improvises in the context of performance: “I have always loved performance. I wanted to be in contact with sound and moving sound in real time.”19

Pauline Oliveros grew up in rural Texas, where she was influenced by the sounds of the natural environment. She also spent hours listening to the radio, remembering that she “loved the static and tuning whistles to be found in between the stations.” She learned to play the piano from her mother and grandmother, and was fascinated when her mother brought home an accordion in 1942. Oliveros was always interested “in what I could hear and the sensual nature of sound.”

After moving from Texas to the San Francisco area in the mid-1950s, Oliveros began to experiment, recording her surroundings by placing a microphone on a window ledge. She discovered that the microphone picked up sounds that she had not heard. Realizing that her own perceptions were selective, filtering some sounds out, she resolved to listen more carefully. She also continued to play the accordion, composing new works for the instrument over the years, including a 1982 composition, The Wanderer, for twenty-three accordions.

Seeking a more organic approach to composition and rejecting conventional musical notation, Oliveros formed the group Sonics with two other composers. Early on, she began to improvise with new resources for electronic and tape music. “It never interested me to cut and splice tape or to wait for numbers to crunch in a computer,” she recalls. “I wanted immediate results. . . . It was really thrilling to hear the sounds that I got and to shape them in real time like a performance, even if it were in a studio.” Eventually, Oliveros developed the Expanded Instrument System (EIS), which provided control during performance of aspects of pitch and timbre that could usually be shaped only in a studio. EIS (pronounced “ice”) is a “continually developing electronic sound-processing environment designed to provide improvising musicians control over various parameters of sound transformation.” Foot pedals and switches control various digital delays, reverberation units, mixers, and processors, with output distributed to speakers around the performance space.

In 1988, Oliveros formed the Deep Listening Band, which has performed worldwide and made recordings. The band has used a variety of sound sources, including trombone, didjeridu, conch shells, voices, pieces of metal, and, of course, the accordion. The band performs in highly resonant spaces and much of its music features a drone, which Oliveros sees “as connecting it to other musics.”

Deep listening has become a central pursuit for Oliveros, who explains the concept as follows:

Composer/performer Pauline Oliveros with her accordion.

The key to multi-level existence is deep listening. Deep listening includes language and its syntax, the nature of sound, atmosphere and environmental context. This is essential to the process of unlocking layer after layer of imagination, meaning, and memory down to the cellular level of human experience. Listening is the key to performance. Responses, whatever the discipline, that originate from deep listening are connected in resonance with being and inform the artist, art, and audience in an effortless harmony. . . . Deep listening is a lifetime practice.

In the examples we have encountered so far, it is already clear that music can draw on a variety of different sound sources and that the music itself rarely remains in the same place. For instance, the Tuvan biphonic singing style has in recent decades traveled widely with touring musicians and through recordings, coming into contact with other soundscapes along the way. Thus as we move through the chapters ahead, we will explore soundscapes not only for shared cultural themes, but also as interactive geographies of sound. It is useful to pause here at the start of this process to consider a musical model for our work: a geographical fugue.

Try It Out |

|

TEACH YOURSELF TO FLY

Throughout this chapter, we have trained your ears to listen. However, many listeners learn about the nature and meaning of musical sound by participating in making it. Although creating some musical styles can require considerable training and background, other styles may be experienced without a technical background. Here you are invited to perform Pauline Oliveros’s composition Teach Yourself to Fly (dedicated to Amelia Earhart), the first of the composer’s series of works titled Sonic Meditations, conceived in the early 1970s. Oliveros’s Sonic Meditations have been performed over the decades in many different contexts, and each performance has a different outcome. You may perform this piece with as many others as you wish. Here are Pauline Oliveros’s instructions for performing Teach Yourself to Fly:

Any number of persons sit in a circle facing the center. Illuminate the space with a dim blue light. Begin by simply observing your own breathing. Always be an observer. Gradually allow your breathing to become audible. Then gradually introduce your voice. Allow your vocal cords to vibrate in any mode which occurs naturally. Allow the intensity of the vibrations to increase very slowly. Continue as long as possible, naturally, and until all others are quiet, always observing your own breath cycle.

Throughout Soundscapes, we will encounter multiple musics in the same geographical location that both overlap and influence each other. Sometimes, as in the case of khoomii singing, one musical style is picked up by others and echoed in different voices, traveling yet further afield. One musician may closely imitate another, adopt and adapt a melody or style, and pass it on. Sometimes musical styles imitate one another strictly, at other moments they interact in unpredictable ways, providing a lively, free counterpoint one to the other. The musical example in Listening Guide 20 embodies all of these processes, a literal “geographical fugue” that involves systematic imitation among four voices. The development of a piece from a main idea, transformed through varying degrees of imitation (also called counterpoint), is the organizing principle of the fugue.

Composed by Ernst Toch, an Austrian musician who lived in Germany before fleeing across Europe and England to finally receive safe haven from Hitler in 1935 in the United States, this work for a “speaking chorus” refers to far-flung places. A composer of a wide range of works, including film music nominated for Oscars in Hollywood, Toch conceived the Fuge aus der Geographie (later translated to English as “Geographical Fugue”) in 1930 as part of an experimental trend in German music. In 1930, Toch could not have suspected that his work would become a deeply functional musical metaphor for his own geographical displacement as well as an ironic statement about our own musical explorations across the globe.

2:52 |

Date of composition: 1930 Date of recording: 1950 Composer: Ernst Toch Form: Four-part fugue Function: Experimental piece designed to explore the potential of a “speaking chorus” |

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR:

• The fast-changing relationships between the four voices (soprano, alto, tenor, and bass) through strict imitation

• The relationship of all of the musical material to the initial phrase (the subject), with additional phrases used for accompaniment or contrasting sections of the piece (the countersubjects)

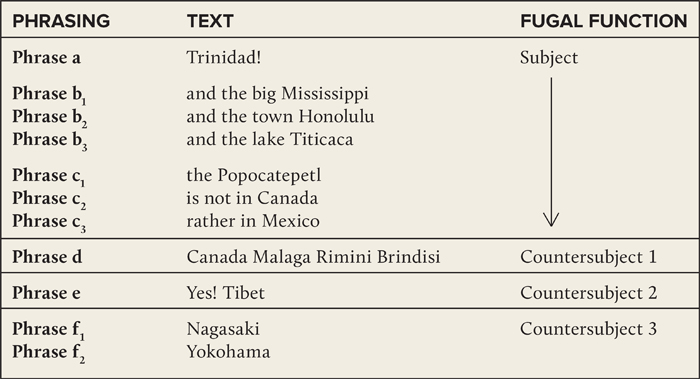

The following chart summarizes the musical phrases (naming them in order of entry by letters) and their fugal function:

STRUCTURE AND DESCRIPTION |

|

0:00 |

Tenor enters with the subject (a-b-c) in its entirety, leading off the EXPOSITION, the presentation of the subject in all voices at the beginning of a fugue. |

0:10 |

Alto enters with the subject, termed the answer. |

0:20 |

Soprano enters with the subject. |

0:27 |

Imitation between alto and tenor. Alto sings phrase e as tenor imitates the word “Tibet.” |

0:31 |

Bass enters with the subject. Tenor drops out. |

0:41 |

The soprano and alto imitate each other with phrase f. |

0:45 |

Soprano drops out. Alto begins variation of phrase d, in rhythmic counterpoint against the bass (e). |

0:51 |

Phrase d continued by the soprano. Texture thins to just one voice. |

0:55 |

Return of the subject in the tenor starts DEVELOPMENT section, where the subject, answers, and countersubjects from the exposition are expanded. Soprano continues with phrase d; alto imitates while bass sings phrase f. |

1:03 |

Soprano picks up the alto line. The bass continues with variations of phrase f. |

1:09 |

Full, four-part imitation begins. Each word is pronounced across the voices in a continuous, heterophonic rhythmic texture with each voice singing the same rhythm, but staggered. This section of a fugue, not based on the subject, is known as an EPISODE, and is used to provide variation. |

1:16 |

Soprano and bass, and alto and tenor, continue as imitating pairs. |

1:20 |

Short, two-voice interlude. |

1:23 |

Bass returns with the subject, followed by the alto in new imitation. Soprano and tenor accompany with the call-and-response of phrase e. |

1:30 |

All four voices in free imitation based on subject and countersubjects. |

1:42 |

Soprano signals the return of the beginning of the subject (phrases a and b) in all four voices. Rhythmic variations abound in all voices. |

1:52 |

Subject repeats in all four voices, begun by the soprano. This close, imitative entry of the subject in all four voices is known as STRETTO. |

2:01 |

The soprano’s arrival at phrase d signals the gradual move into a homophonic texture as all voices arrive at a unison of the first half of phrase d. There is no imitation. Increasing volume at the unison signals a new section. |

2:11 |

Tenor, alto, and bass, respectively, enter with the subject in three different rhythmic variations. The three voices then form an imitating trio with phrases b1, b2, and b3, gradually decreasing the pauses until they produce a homophonic texture on the word “Mississippi.” The soprano sings a rhythmically altered subject. This section marks the final entries of the fugue subject. |

2:36 |

Beginning of the CODA that concludes the piece. Each voice sings phrase d only, moving from the soprano down to the bass. |

2:43 |

Soprano rolls the “r” in “Trinidad” to start a pedal point, a long sustained pitch used at the end of many pieces of Western tonal music to provide concluding tension. Volume level increases, with gradually diminishing pauses between words. |

2:50 |

Three of the voices sing an accented “Trinidad” in unison to end the piece. |